A 64-year-old man with hypertension, dyslipidemia and a family history of coronary artery disease presented with an inferior wall ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). He was transferred immediately to the catheterization laboratory for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI). Following insertion of a 6 Fr sheath in the right radial artery, the standard 0.035-inch J wire could not be advanced beyond the elbow. Arteriography revealed a 360-degree loop of the right radial artery (Figure 1 A). Following multiple attempts to cross the loop with a 0.035-inch hydrophilic J wire, it finally entered in a small branch arising from the loop (remnant recurrent radial artery) and even though it reached the ascending aorta, the patient could not tolerate the advancement of a right diagnostic catheter due to severe pain. Repeat arteriography showed generalized spasm and ruled out blood extravasation.

Figure 1

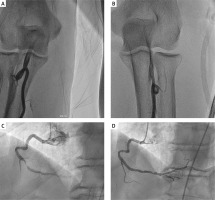

A – Right radial arteriography demonstrating a 360-degree loop. B – Left radial arteriography demonstrating a 360-degree loop. C – Left anterior oblique angiographic view showing subtotal occlusion in the mid portion of the right coronary artery. D – Final angiographic result following implantation of a drug-eluting stent

It was decided to switch to the left radial access, but the standard 0.035-inch J wire could not be advanced in the left radial artery. Arteriography again showed a 360-degree loop, and maneuvers to cross it were again unsuccessful (Figure 1 B). Since the patient could no longer tolerate the manipulations, we switched to right femoral access. The left coronary system was atheromatous but without significant stenoses. The right coronary artery had a subtotal occlusion with a high thrombus burden in the mid portion (Figure 1 C), and a drug-eluting stent was successfully implanted to treat the culprit lesion (Figure 1 D). The patient was discharged 4 days later, having normal left ventricular ejection fraction. A detailed report of the procedure describing the bilateral 360-degree radial loops was provided to him.

Radial access reduces vascular complications compared to femoral access [1]. However, a radial loop is a challenging anatomical variation that increases the complexity of transradial catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention, often leading to conversion to an alternative access site or to complications such as perforation [2]. The incidence of radial loops is approximately 1–2.3%, with a procedure failure rate of around 37% [2, 3]. Different interventional strategies can be applied to tackle a radial loop. A 0.035-inch hydrophilic or a coronary wire can be used to cross the loop and try to straighten it. Mother-and-daughter techniques, such as pigtail-assisted tracking (use of a pigtail catheter to assist tracking of the diagnostic catheter through the loop), balloon-assisted tracking (use of a partially inflated balloon protruding at the catheter tip over a 0.014ʺ wire) and use of a low-profile microcatheter over a microwire in order to cross and straighten the loop and assist catheter tracking, have been described and can be effective [4]. If these approaches fail, then the operator should consider alternative access. There are no data suggesting that the presence of a radial loop increases the likelihood of a radial loop on the contralateral side.