Breast implants were first approved in 1962, and today more than 300,000 are implanted annually in the United States [1]. With the rise of gender-affirming surgery, the number of these implants and their associated complications have also increased. A 10-year prospective study reported rupture rates of 7% to 10% [2]. This rupture may be spontaneous due to degeneration of the implant or may be secondary to mammography or trauma. Cardiac surgery is also a rare but important known cause of breast implant rupture.

Complications related to breast implants during cardiac surgery are very rare in the literature and are usually reported as case reports. Therefore, there are limited data on the risks in this regard. In a study by Coombs et al. on 78 patients who underwent cardiac surgery and pacemaker surgery, 5 patients had intraoperative rupture, and 19 patients had postoperative implant complications [3]. However, this risk may differ in transgender women due to anatomical differences. We present a case of intraoperative extracapsular breast implant rupture in a transgender woman who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

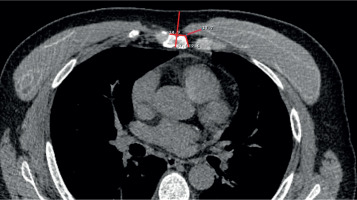

A 53-year-old transgender woman patient (body surface area: 1.97 m2) applied to our clinic with complaints of chest pain for 6 months. She had no additional disease other than hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Her vital signs were stable. No pathological findings were detected in her examination and laboratory parameters. She had bilateral breast implants 20 years ago and had a history of rhinoplasty 15 years ago. Coronary computed tomographic angiography revealed extensive coronary artery disease (CAD), and then coronary angiography (CAG) was performed. There was 50% stenosis in the left main coronary artery (LMCA), 90% in the left anterior descending artery (LAD), 70% in the diagonal artery, and 90% stenosis in the right coronary artery, which was dominant. The circumflex artery (Cx) was nondominant and thin, and 95% stenosis was detected. Ejection fraction was normal in transthoracic echocardiography and no valve pathology was detected. The patient was evaluated by the multidisciplinary heart team, and it was decided to perform CABG. Preoperative thoracic computed tomography (CT) showed bilateral intracapsular rupture, degeneration, and calcifications with silicone implants (Figure 1). On physical examination, capsules were palpated in both breasts, there was no evidence of symmastia, and the breast had lost volume asymmetrically. The patient was given detailed information about minimally invasive surgery and median sternotomy (MS) operations and their risks, and the patient preferred MS.

Figure 1

Preoperative thoracic computed tomography shows bilateral intracapsular rupture, degeneration, and calcifications

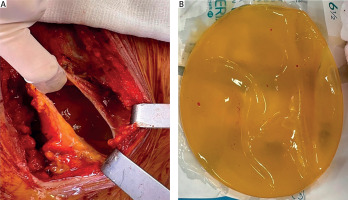

After MS, the patient underwent CABG for the LAD, diagonal, and right coronary arteries (RCA) using the left internal mammary artery and saphenous vein grafts. Since the Cx was nondominant and thin, it was not suitable for bypass. No problems occurred during MS and the operation, but after the operation was completed, it was observed that the left breast implant had ruptured while passing through the subcutaneous sutures after sternum wiring. Due to extracapsular rupture, the silicone inside had spread over the sternum. Thereupon, the plastic and reconstructive surgery team joined the operation. Anterior capsulectomy was performed with the old, calcified, and capsule-engaged prosthesis. Scoring was applied to the posterior capsule, and the silicone material was removed from the area with saline irrigation (Figure 2). Fibrin glue (Tisseel) was applied to the breast pouch for bleeding control and pouch closure. The sternal wires were removed again to reduce the risk of mediastinitis due to the implant being 20 years old, its deteriorated structure, and the contamination of the sternum and sternal wires. The mediastinum was washed with oxygenated water, povidone iodine, and topical rifampin, and the sternum was wired again. Cardiopulmonary bypass time was 140 min, and cross clamp time was 72 min. Postoperatively, there was a total of 800 ml of serous drainage, and no blood product was required. Vancomycin and cefepime were initiated after consulting the infectious diseases clinic after the operation. The patient was discharged from the intensive care unit on the second day after surgery and from the hospital on the eighth day with cefixime without any complications. Postoperative follow-up continued for the purpose of re-application of the left breast implant.

Figure 2

A – Intraoperative view of the capsule opening and silicone spreading over the sternum after breast implant rupture. B – Intraoperative view after the silicone material was removed

Breast augmentation surgery is an aesthetic surgery that is popular and desired by both women and transgender women due to the change in their perception of beauty. Since the first desired change during male-to-female surgery is typically breast development, it is very common among transgender women. However, in patients who require cardiothoracic surgery due to anatomical proximity, there is a risk of breast implant rupture, especially if emergency intervention is required. There are insufficient data on the risks in this regard. Apart from the 78-patient study by Coombs et al., there are a few case reports [3]. Cui et al. reported the rupture of a saline breast implant after robotic-assisted lung surgery [4]. Nisi et al. reported breast implant rupture as a complication of cardiac surgery in MS [5]. However, these patients were cisgender women, and since these patients and transgender women have different anatomical features, the risk of rupture and surgical approaches differ. We present a case report of a transgender woman who underwent CABG and had an intraoperative extracapsular breast implant rupture. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of breast implant rupture during CABG in a transgender woman.

The anatomy of transgender women differs from that of cisgender women. The anatomical difference is actually due to the female and male skeletal structure, and therefore implant preferences are different. Transgender women have to choose a medium-projection but wide-based prosthesis instead of a full projection because they have a lower volume of breast and soft tissue to cover the breast implant [6]. The surgeon’s choice is the same for aesthetic purposes, and these prostheses are generally placed in the Dual II plane by separating the pectoral muscle from the sternum medially. In cisgender women, since the chest wall is narrow and the soft tissues are more adequate, full-projection implants are primarily preferred by both the surgeon and the woman. Therefore, the probability of damage to the prosthesis in emergency or elective cases requiring sternotomy is higher than in cisgender women. The patient in our case also had a body surface area of 1.97 m2, and a larger and wider-based implant was used compared to an average cisgender woman. As seen in Figure 1, due to the intracapsular tear in the preoperative period, the implant being degenerated, and the use of a larger and wider-based implant, the distance between the implant capsule and the left side of the sternum has decreased to 17 mm. We can say that placing a breast implant this close to the sternum increases the risk of intraoperative rupture. It may rupture during MS, or it may rupture during the sternal wiring phase, especially during the use of the intercostal space. In our case, no rupture was observed during the operation, but we observed a rupture in the left breast implant during subcutaneous sutures. The implant capsule may be damaged by cauterization of the intramuscular veins for bleeding control. In addition, in cases where the muscle layer is very small, such as 17 mm, as in our patient, the subcutaneous sutures used to provide sternal stability may cause extracapsular rupture. As the age of the implant increases, the risk of implant rupture also increases [7]. Our patient’s 20-year-old implant may have increased the risk of rupture.

The fact that the implant is old greatly explains the formation of intracapsular tears. Even after the transition to gel technology in the literature, the increase in implant-related breast cancer cases, especially, necessitates that the prostheses must be renewed after a certain period of time. The formation of capsules around the implant is a natural process and is more common in implants with smooth surfaces, and the prosthesis removed from this patient was of the same type. Silicone is naturally protected from other body tissues by a protective mechanism, thus fixing it in place. In this patient, the capsule was extremely thin medially due to the male anatomy. The capsule, which lost its strength during sternotomy and wiring, could not protect the implant.

Many operations in cardiac surgery can be performed with the classical method of MS, as well as with minimally invasive methods, which have become increasingly widespread in recent years. Depending on the type of operation, right or left thoracotomy is performed from different intercostal spaces. However, thoracotomy performed in patients with breast implants may increase the risk of implant rupture. In the study by Coombs et al., intraoperative rupture was observed in 5 patients who underwent surgery with the minimally invasive technique, while no intraoperative rupture was observed in those who underwent surgery with MS. However, long-term complication rates were higher in those who underwent MS [3]. Je et al. reported a minimally invasive atrial septal defect and tricuspid valve repair operation with capsule preservation in a patient with breast implants [8]. Cetinkaya et al. reported explantation and reimplantation of breast implants to facilitate minimally invasive mitral valve surgery and cryoablation of atrial fibrillation [9]. However, it is important to discuss these risks in detail with the patient and leave the choice to the patient. We informed our patient about MS and minimally invasive methods before the operation and made an operation plan with MS upon the patient’s request. Although we consider that the risk of rupture is lower with MS, the fact that the patient is a transgender woman, anatomical differences in the muscle structure, the use of a larger and wider implant, the presence of intracapsular rupture and degeneration in the preoperative period, the fact that the implant is 20 years old, and the distance between the implant and the sternum is short may have increased the risk of extracapsular rupture in our case.

Another important point about intraoperative breast implant rupture in cardiac surgery is that the material inside contaminates the surgical field. As seen in Figure 2, because the silicone inside the capsule is 20 years old, its structure and consistency have deteriorated, spreading and causing contamination of the sternum and sternal wires. We removed the sternal wires again to minimize the risk of possible mediastinitis. We meticulously washed the mediastinum with oxygenated water, povidone iodine, and topical rifampicin due to possible contamination. After the operation, we consulted the infectious diseases clinic and ensured that she received broad-spectrum antibiotics. With these precautions, we discharged our patient without any signs of infection. Another point is that we believe these protection methods regarding possible infection should be given more attention, especially in patients who have valve surgery, which carries a higher risk of endocarditis.

In cardiac surgery, the surgical strategy of patients with breast implants should be decided together with the patient. In the preoperative period, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging help determine the surgical plan. These images, together with the multidisciplinary evaluation of the patient with the plastic surgery clinic and preservation of the capsule to open the lateral plane during the sternotomy incision, can prevent possible complications. However, this rupture risk may be higher in transgender women compared to cisgender women.

In cardiac surgery, patients with breast implants should be evaluated with preoperative imaging methods to determine surgical proximity for possible rupture risk, and the operation strategy should be planned in a multidisciplinary manner. The rupture risk of breast implants in transgender women may be higher than in cisgender women due to anatomical differences. However, future studies are needed on this subject, for which we have limited data.