Introduction

Percutaneous device closure is the gold standard for the majority of secundum atrial septal defects. However, some defects remain a challenge, including multiple defects associated with an aneurysmal atrial septum, which can pose significant difficulty for both interventional cardiologists and echocardiographers. Nevertheless, interventional closure of such defects has proven to be safe and effective [1]. We present a simple technique for the transcatheter closure of multiple large atrial septal defects in a patient with a highly aneurysmal atrial septum.

Case report

The patient was a 6-year-old child weighing 18 kg. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a significantly dilated right atrium and right ventricle (3.9 cm, z-score +3.1), an atrial septal defect with the largest dimension measuring 7 mm, a significant left-to-right shunt, a main pulmonary artery measuring 20 mm, and branches measuring 12 mm each, but no signs of pulmonary hypertension (peak gradient of tricuspid valve regurgitation was 30 mm Hg).

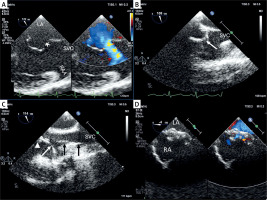

After an interdisciplinary discussion, the patient was deemed suitable for an interventional attempt to close the atrial septal defects. Under general anesthesia, a transesophageal echocardiogram was performed, revealing an aneurysmal atrial septum bowing into the right atrium, with two atrial septal defects measuring 8 mm (superior) and 3 mm (inferior), separated by a 9 mm segment of thin tissue (Figure 1 A). The rims were preserved, with a 4 mm aortic rim, a 12 mm superior vena cava rim, and a 6 mm inferior vena cava rim. The diameter of the aneurysm base was 15 mm, and the total septal length was 34 mm.

Figure 1

Transesophageal echocardiographic guidance of percutaneous closure of multiple atrial septal defects (ASDs) in a patient with highly aneurysmal atrial septum. A – In bicaval view an aneurysmal atrial septum bowing into the right atrium, with two ASDs superior measuring 8 mm (larger asterisk) and inferior 3 mm (smaller asterisk), separated by a thin highly aneurysmal segment of tissue. B – A 90-degree angled 4 Fr Berenstein catheter pointing towards the atrial septum. C – A wire (black arrows) positioned in the superior vena cava (SVC) stabilizing the long sheath (white arrow head) while the Berenstein catheter (white) is directed towards the right atrial appendage prior to being oriented towards the interatrial septum. D – The implant is in its correct position, with a small residual shunt through the central part of the device

LA – left atrium, RA – right atrium, RAA – right atrial appendage, SVC – superior vena cava.

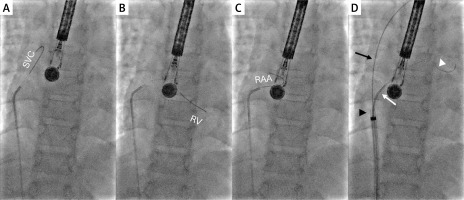

Under ultrasound guidance, standard femoral vascular access was obtained. A 4 Fr multipurpose catheter over a 0.018ʺ hydrophilic wire was advanced into the superior vena cava and gradually pulled back to the right atrium, aiming to cross the higher (larger) defect. The aneurysmal septum was bulging toward the right atrium. Both the wire and the catheter slid over the septal tissue toward the superior vena cava, the right atrial appendage, or the right ventricle. The catheter was replaced with a 90-degree angled 4 Fr Berenstein catheter (Figure 1 B). It was anticipated that the angled-tip catheter would offer better access to the higher defect, but it kept falling away from the interatrial septum, and the soft wire was sliding off the aneurysmal tissue (Figures 2 A–C). A similar situation occurred with a 4 Fr Judkins Left catheter.

Figure 2

Percutaneous closure of multiple atrial septal defects in a patient with highly aneurysmal atrial septum. A 90-degree angled 4 Fr Berenstein catheter pointing towards the atrial septum, a soft wire slides to the superior vena cava (A), right ventricle (B) or right atrial appendage (C). Over a standard 0.035′′ buddy wire (black arrow) placed in the superior vena cava, the tip (black arrowhead) of a nominal (for the desired 15 mm septal occluder) 8 Fr long sheath was positioned at the level of the larger atrial septal defect, and the 90-degree angled 4 Fr Berenstein catheter was rotated towards the defect, which was then easily crossed with a soft wire (white arrowhead) (D)

RV – right ventricle, RAA – right atrial appendage, SVC – superior vena cava.

Finally, an 8 Fr long sheath was introduced to the right atrium/superior vena cava junction over a 0.035ʺ wire parked in the superior vena cava (Figure 2 D). The wire was kept in the superior vena cava and the innominate vein to stabilize the long sheath close to the interatrial septum, and the tip of the Berenstein catheter was advanced from the sheath to the right atrium and rotated towards the septum (Figures 1 C, 2 D). From this position, the 0.018ʺ wire was easily passed through the higher defect to the left atrium and the left lower pulmonary vein. Next, the 0.035ʺ wire was removed, and the sheath was advanced into the left atrium.

An oversized 15 mm Amplatzer Septal Occluder (Abbott) was implanted into the larger defect on the first attempt. The transesophageal echocardiography evaluation showed a stable position of the occluder covering both defects with no residual leaks (Figure 1 D). The sheath was removed, and hemostasis was achieved with manual compression. The procedural and fluoroscopy times were 40 min and 12 min, respectively.

Post-procedurally, echocardiography within 24 h confirmed device stability with no residual leaks. No arrhythmias were observed in the periprocedural period. The patient was discharged the following day on a 6-month course of aspirin. A routine 1-month follow-up revealed no adverse symptoms, normal sinus rhythm on electrocardiogram, and echocardiography confirmed the device’s appropriate position with no residual shunting or interference with surrounding structures.

Discussion

In our case, closing the atrial septal defect posed a challenge due to the presence of multiple defects within a highly aneurysmal atrial septum bowing towards the right atrium, which made it difficult to pass the guidewire through the preferred larger defect. Several attempts to cross the defect with differently shaped catheters were unsuccessful. Alternatively, an approach from the superior vena cava could have allowed easier crossing of the defect, but subsequent deployment of the device would have been more challenging, with a potentially higher risk of complications. The technique we used relies on typical equipment employed for atrial septal defect closure. A nominal long sheath (8 Fr) for the desired device (15 mm) was introduced close to the larger defect and stabilized with a separate buddy wire parked in the superior vena cava. This provided a stable, closer-to-the-septum position for the angled catheter, which after rotation gave an en face approach to the defect. The remainder of the procedure was straightforward.

The diameter of the device was selected according to the length of the base of the aneurysm. It was anticipated that the thin, floppy tissue between the two defects would stretch or tear to allow complete expansion of the occluder’s waist and the firm edges of the aneurysm would provide enough grip for the discs. That was the case in our patient. However, if the margins of the larger defect turn out to be too firm to allow complete formation of the waist, the septum between the two defects could be ruptured with a balloon or a snared wire, and the created single defect could be closed with one, oversized device. Alternative defects could be treated with separate devices, implanted during a single procedure or sequentially. In the latter scenario, after closing the larger defect, the decision to treat the smaller one should be made after reassessment of its size and hemodynamic impact.

For multiple defects, it is crucial to cross the largest or most central defect to enable closure of both defects with a single device. In such cases, precise echocardiographic guidance is particularly important. However, this guidance can be difficult, as artifacts created by the guidewire and changes in the defect’s geometry due to the guidewire can obscure the determination of which defect is being crossed. Therefore, comprehensive imaging sweeps are necessary to accurately assess the defect locations [2].

Three-dimensional echocardiography is highly beneficial in guiding the closure of multiple defects, as it greatly facilitates navigation and helps confirm the path of the guidewire through a specific defect. Unfortunately, a limitation of this method is the unavailability of 3D transducers for children weighing less than 20 kg, which prevented us from using 3D imaging in this case [3].

Conclusions

This case highlights the complexity of percutaneous closure of multiple atrial septal defects within an aneurysmal septum. Successful closure requires precise imaging guidance and strategic navigation to cross and close the appropriate defect. Our approach demonstrated that with careful planning and a buddy wire technique, complex atrial septal defect configurations can be effectively managed, resulting in a stable and favorable outcome.