Introduction

Steatotic liver disease (SLD) is an umbrella term characterized by abnormal lipid accumulation in the liver. Under the revised nomenclature, it includes several subgroups: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), their combination (metabolic alcohol-associated liver disease – MetALD), and other rare causes of hepatic steatosis. Among these, MASLD is the most prevalent, with global estimates suggesting a prevalence of approximately 30 [1], and rising rates observed over recent decades. Despite its high prevalence, effective treatment options remain limited. Individuals with MASLD have an increased risk of both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality compared to those without the disease, with cardiovascular disease (CVD) representing the leading cause of death in this population [2]. The pathogenesis of MASLD is best explained by the multiple-hit hypothesis, which posits that various concurrent factors contribute to the onset and progression of the disease [3].

Previously, it has been noted that the prevalence of MASLD is higher in men compared to women [4]. Recent evidence suggests that the MASLD prevalence and mortality in women are increasing at a sharper rate [5, 6]. Interestingly, compared to men, women of reproductive age demonstrate a reduced vulnerability to developing MASLD, highlighting the significant role of the hepato-ovarian axis and estrogen signaling in the liver’s physiological processes in females [7]. In women, the ef fects of estrogen on the liver are predominantly mediated through the estrogen receptor α(ERα), which, when activated, plays a key role in reducing lipid synthesis, uptake, and storage while enhancing lipid breakdown and export. However, despite this protective mechanism, the likelihood of women developing MASLD fluctuates across their reproductive lifespan [8]. Hormonal, endocrine, and metabolic factors, including changes in body fat distribution and muscle mass and quality, can impact the risk of MASLD during different stages of a woman’s reproductive life. Additionally, women with MASLD often present with distinct clinical and pathological characteristics compared to men [7].

Menopause, the natural cessation of menses, is accompanied by a significant slowing of reproductive hormone production in the setting of physiological aging. This loss of protective estrogen effects, in tandem with the ever-present burden of advanced age, is thought to contribute to the increased rates of cardiovascular disease and metabolic changes seen in this population [9]. This study aimed to explore the prevalence of SLDs among pre- and post-menopausal women in the U.S. population as well as the factors that predispose post-menopausal women to SLD development.

Material and methods

Data source

This cross-sectional study is based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database (2017 – March 2020 Pre-pandemic cycle) series conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This is a continuous, multistage, nationally representative survey of the noninstitutionalized US civilian population, collected in 2-year stages. We included participants 18 years of age or above and with available controlled attenuation parameters (CAP) and liver stiffness measures (LSMs) from vibration-controlled transient elastography. Age, sex, race, medical conditions, and alcohol use were collected during in-home interviews. Race was included because of known racial differences in the risk of SLDs and liver fibrosis [10, 11].

Ethics consideration

The original survey received approval from the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board. The present study was granted exemption by the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board due to the complete de-identification of the data set used in the analysis.

Definition of different steatotic liver disease categories: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, metabolic-alcohol-related liver disease, and alcohol-related liver disease

Metabolic risk factors were defined according to new consensus nomenclature as follows: systolic/diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 130/85 mm Hg or taking hypertension medications; body mass index ≥ 25 (≥ 23 if Asian) or waist circumference > 94 cm in men or > 80 cm in women; fasting plasma glucose level of ≥ 100 mg/dl or hemoglobin A1c ≥ 5.7% or diabetes mellitus medications; serum level of triglycerides of ≥ 150 mg/dl or lipid-lowering agent; high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level of < 40 mg/dl in men or < 50 mg/dl in women or lipid-lowering agent [12].

Steatotic liver disease was defined using the new Delphi consensus nomenclature. (1) MASLD = steatosis (CAP of ≥ 288 dB) + ≥1 metabolic risk factor. (2) MetALD = MASLD + average daily alcohol intake 20–50 g (women)/30–60 g (men) in the past 12 months. (3) ALD = steatosis + average daily alcohol intake > 50 g (women)/> 60 g (men) + ≥1 metabolic risk factor or steatosis + average daily alcohol intake ≥ 20 g (women)/≥ 30 g (men) + no metabolic risk factors. (4) Specific etiology or cryptogenic SLD = steatosis + no metabolic risk factors + average daily alcohol intake < 20 g (women)/< 30 g (men) [12]. Specific etiologies include drug-induced liver injury, monogenic diseases (e.g., Wilson disease, inborn errors of metabolism), and miscellaneous causes (e.g., HCV and celiac disease), while cryptogenic reflects no identifiable cause. liver stiffness measures of ≥ 11.7 kPa was used to identify patients with advanced liver fibrosis [13].

Assessment of menopausal status

To determine menopausal status, we used two questions from the NHANES Reproductive Health Questionnaire: (1) Have you had at least one menstrual period in the past 12 months? and (2) What is the reason that you have not had a period in the past 12 months? Participants were considered postmenopausal if the answer to the first question was “No” and the answer to the second question was “Menopause/Hysterectomy” [14]. Participants were considered premenopausal if the answer to the first question was “Yes” or if the answer to the first question was “No” and the answer to the second question was “Pregnancy”, “Breastfeeding”, “Medical conditions/treatments”, and/or “Other”.

Study population

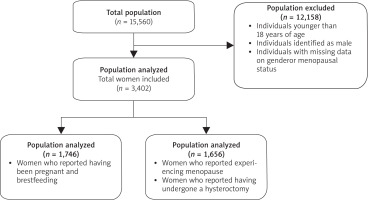

Of the initial 15,560 participants, 12,158 individuals were excluded due to being younger than 18 years, identified as male, or having missing data on gender or menopausal status. The final analytical sample comprised 3,402 women, categorized into two groups: 1,746 premenopausal women and 1,656 postmenopausal women, defined as below (Figs. 1, 2).

Statistical analysis

Prevalence estimates for SLD, MASLD, MetALD, and clinically significant fibrosis were computed using survey weights to reflect the U.S. adult population. Age-adjusted prevalence rates were calculated using direct standardization to the 2000 U.S. Census population. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were reported for key predictors, including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, hypertension, and ethnicity-adjusted waist circumference. All analyses adhered to the NHANES analytic guidelines, ensuring proper use of survey design variables, including primary sampling units, strata, and weights. Missing data were managed using listwise deletion to maintain the integrity of the analysis. This methodological approach ensures robust, generalizable findings representative of the U.S. adult population. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 17 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX), with a significance level defined as p < 0.05.

Results

In our analysis, Table 1 outlines the demographic distribution, which reveals significant differences between premenopausal and postmenopausal women. 65.81% of premenopausal women were in the 18–39 age group, whereas 65.10% of postmenopausal women were aged 60 years or older, highlighting the predominant age range in each group. Racial and ethnic composition varied significantly, with a higher proportion of non-Hispanic White individuals in the postmenopausal group (41.85%) compared to the premenopausal group (32.59%). Metabolic risk factors were more prevalent in postmenopausal women. The prevalence of overweight and obesity (30.68% vs. 23.14%, respectively) across all classes was markedly higher in postmenopausal women, whereas the prevalence of overweight and obesity in premenopausal women was significantly lower (23.14% and 18.90%, respectively). Additionally, the rates of hypertension (75.85% vs. 35.82%, p < 0.001) and diabetes (33.94% vs. 15.29%, p < 0.001) were significantly higher in postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women, reinforcing the association between menopause and metabolic dysfunction. Differences were also observed in education and marital status between the two groups, where a higher proportion of postmenopausal women had attained only a high school education or lower (40.89%) compared to premenopausal women (31.27%) whereas college graduates were more prevalent among premenopausal women (62.09% vs. 59.00%). Marital status also showed significant variation, with a greater proportion of postmenopausal women living alone (51.27%) compared to premenopausal women (42.33%), potentially indicating social or economic differences that may further influence health outcomes.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics stratified by premenopausal and postmenopausal women

Prevalence of liver diseases in postmenopausal and premenopausal women

Among premenopausal and postmenopausal women, the prevalence of different categories of liver disease was analyzed; the results are presented in Table 2. Steatotic liver disease was more common in postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women (34.57% vs. 23.49%), with a similar difference observed for MASLD (32.79% vs. 21.70%). The prevalence of MetALD was also higher in postmenopausal women (17.04%) than in premenopausal women (13.52%). Additionally, liver fibrosis was more frequent in postmenopausal women (3.41%) compared to premenopausal women (2.63%), suggesting potential differences in disease progression. The association between liver diseases and postmenopausal women evaluated by multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Table 2

Prevalence of liver diseases among premenopausal and postmenopausal women

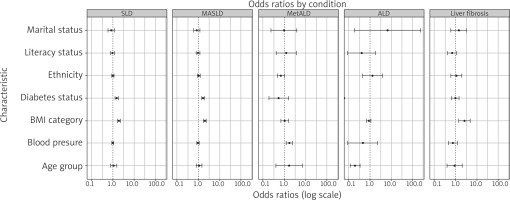

The key predictors were examined and reported as OR with 95% CI. Body mass index was the most significant predictor of SLD (OR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.68–2.23) and MASLD (OR = 1.97, 95% CI: 1.73–2.24), reinforcing the critical role of adiposity in liver disease pathogenesis. Diabetes status was another strong predictor, showing increased odds for SLD (OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.28–1.81) and MASLD (OR = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.42–1.88) (Table 3).

Table 3

Predictors of steatotic liver disease and liver fibrosis in postmenopausal patients

Notably, age did not significantly predict SLD, MASLD, or MetALD, with confidence intervals overlapping 1.00. However, age was inversely associated with ALD (OR = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.12–0.34), suggesting that younger individuals may be at higher risk for ALD. Ethnicity, literacy status, and marital status were not strongly associated with liver disease outcomes, with OR values close to 1.00. Hypertension was a notable predictor of MetALD (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.26–2.47), highlighting the interplay between cardiovascular and hepatic health.

Discussion

Our study provides compelling evidence of the heightened prevalence of different liver diseases among postmenopausal women compared to their premenopausal counterparts. Using data from NHANES 2017–2020, we found that postmenopausal women exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of SLD (34.57% vs. 23.49%) and MASLD (32.79% vs. 21.70%). These findings are particularly concerning given the concurrent rise in metabolic comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia in this population, all of which were independently associated with increased odds of SLD development.

Estrogen has long been recognized for its protective role in hepatic metabolism, exerting anti-inflammatory and lipid-regulating effects through ERαsignaling in hepatocytes [15]. However, the transition to menopause is marked by a sharp decline in estrogen levels, leading to shifts in lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, and an increased propensity for hepatic fat accumulation. Prior research has demonstrated that estrogen deficiency contributes to hepatic steatosis through dysregulation of lipid homeostasis, reduced mitochondrial function, and altered adipose tissue distribution. The significant burden of SLD among postmenopausal women in our study is consistent with these mechanistic insights and highlights the need for targeted interventions that address metabolic health in this vulnerable population.

Interestingly, while MASLD and MetALD were significantly more prevalent in postmenopausal women, the prevalence of ALD was marginally higher in premenopausal women (0.44% vs. 0.07%, p = 0.045). This discrepancy may reflect differences in drinking behaviors between the two groups, as well as the influence of estrogen in mitigating the hepatotoxic effects of alcohol. Notably, despite the increased prevalence of SLD in postmenopausal women, we did not observe significant differences in self-reported alcohol consumption between those with and without SLD, underscoring the predominant role of metabolic dysfunction rather than alcohol intake in driving liver disease progression in this demographic.

Recent evidence indicates that SLD in postmenopausal women is not only linked to metabolic disorders but also associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease. The decline in estrogen after menopause contributes to adverse metabolic changes – such as dyslipidemia, central adiposity, and insulin resistance – that underpin both SLD and cardiovascular risk [16, 17]. For instance, obesity remains a significant predictor of SLD (OR = 1.94, p < 0.001), emphasizing that interventions focused on weight management, dietary modification, and physical activity can be doubly beneficial by mitigating risks for both liver and heart diseases.

Moreover, the literature suggests that the presence of SLD in postmenopausal women may serve as a marker for heightened cardiovascular risk, independent of traditional risk factors. This reinforces the need for comprehensive screening and targeted management strategies in this population. Emerging data also point to a potential role for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in providing hepatoprotective benefits and possibly improving cardiovascular outcomes by modulating metabolic dysfunction. In summary, an integrated public health approach that emphasizes early detection, lifestyle modifications, and metabolic control – potentially augmented by HRT – could be pivotal in addressing the dual challenges of SLD and cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women.

Our study has several strengths, including the use of a nationally representative dataset, robust statistical analyses incorporating NHANES survey weights, and the application of updated SLD nomenclature to classify disease subtypes. However, we acknowledge certain limitations. The cross-sectional nature of NHANES prevents the establishment of causal relationships, and the reliance on self-reported alcohol intake may have led to underestimation of ALD prevalence, lack of biopsy for histologic validation, and no established CAP cut-off value for MetALD. Additionally, the lack of longitudinal follow-up data limits our ability to assess disease progression over time.

Conclusions

Our findings underscore the significant burden of SLD among postmenopausal women, with metabolic dysfunction emerging as the predominant driver of disease. Given the increasing prevalence of MASLD and MetALD in aging populations, future research should explore targeted prevention strategies, including lifestyle interventions, pharmacologic therapies, and potentially hormone-based treatments. Addressing the unique metabolic challenges of postmenopausal women may ultimately reduce their risk of advanced liver disease and associated complications, thereby improving long-term health outcomes in this growing demographic.