Summary

To date, few studies have been conducted on the significance of the Vulnerable Elders-13 Survey (VES-13) scale in predicting postoperative complications in older patients undergoing cardiac surgery. This is the first study in which a comparison between the VES-13 and EuroSCORE scales was conducted. As shown in our study, both scales play an important role in pre-operative evaluation of elderly patients, but should not be used interchangeably.

Introduction

The aging of societies and the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases as well as the increased incidence of acute disorders mean that elderly patients constitute a dominant group of patients in many hospital departments, including cardiac surgery [1, 2]. Data from the National Health Fund Report in 2010 indicate that older patients, who constitute about 14% of the Polish society, use more than 60% of funds allocated for hospitalizations [3]. Compared with younger patients, the elderly ones are most often admitted for more severe health conditions, stay in the wards longer, require more diagnostic tests and have a higher rate of re-hospitalization [4]. To a large extent, this situation is often due to an atypical picture of diseases, risks associated with pharmacotherapy and cognitive impairment, as well as difficulties with the subsequent compliance with recommendations, and finally significant disability of the elderly patients [2]. In order to reduce the risk of complications during hospitalization and to diminish the likelihood of re-hospitalization, we have attempted to improve the prognosis by various diagnostic tools for several years to help identify the high-risk patients and guide further diagnostic and therapeutic activities, while caring for this selected population [5, 6]. The following scales are tools of recognized value to determine certain geriatric problems, i.e. Vulnerable Elders-13 Survey (VES-13) and a comprehensive geriatric assessment (COG), which is performed when a patient receives 3 points in the VES-13 scale. The scales allow immediate and more accurate diagnosis of health problems of a patient. They plan the procedure during the hospitalization and after the patient’s discharge from the hospital [7]. The disadvantage of COG is its time-consuming complexity and a need to involve additional trained medical personnel. The scale of the prediction of perioperative complications in the cardiac surgery departments is the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) scale.

Aim

The aim of this study is to compare the applicability of the VES-13 and EuroSCORE scales in patients > 60 years of age, subjected to cardiac surgery, in predicting the perioperative complications.

Material and methods

Analysis of postoperative complications was made based on the division of patients in terms of the VES-13 < 6 points, VES-13 ≥ 6 points, EuroSCORE (ES) < 6 points, EuroSCORE (ES) ≥ 6 points. The study included 100 patients ≥ 60 (60.83 ±6.18) years old, hospitalized at the Department of Cardiac Surgery in 2017. Among the patients studied there were 61 men of average age 68.43 ±6.4 years and 39 women of average age 71.1 ±5.52 years.

The VES-13 scale is a questionnaire containing 13 questions, including: age subgroups 60–74 years (0 points), 75–84 years (1 point), over 84 years (3 points), self-assessment of health – two categories: “great” or “good” (0 points) and “average” or “bad” (1 point) and two categories of questions regarding the deterioration of functional and physical fitness. Questions 3–8 include the assessment of the difficulty in performing four functional activities (shopping, disposing of own money, performing light housework, bathing) and three physical ones (going through the room, bending, crouching). The self-reliant patient receives 0 points in each activity, with a difficulty in performing one of them – 1 point, and if two or more activities are impaired, the patient receives 2 points. The second category of disorders includes questions 9–13 regarding three physical activities (lifting, and lifting heavy objects weighing about 4.5 kg, reaching or stretching arms above shoulders and passing about 1.5 km), and two functional ones (writing or maintaining small objects, doing heavy housework). If the patient is capable of performing these activities, she/he receives 0 points, but the occurrence of any difficulty in at least one of them results in 4 points being awarded instantly. Each positive answer to questions 3–13 results in 1 point; hence the total score ranges from 0 to 15 points.

The interpretation of the VES-13 scale: a patient who scores 0-5 points does not require any geriatric care, ≥ 6 points the ailing patient after discharge from the hospital is referred to the Geriatric Clinic.

The EuroSCORE (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation) scale allows the assessment of surgical mortality among patients undergoing cardiac surgery. It is based on the results of an observational study, which covered 20 thousand patients from 128 hospitals from 8 European countries. A patient receives 1 point for the age 60+, another point every 5 years, for female sex, for respiratory diseases treated with steroids, for ejection fraction (EF) ≥ 30%, and 2 points for: non-cardiac vascular changes, neurological disorders, creatinine ≥ 200 μmol/l, nitroglycerin infusion, myocardial infarction < 60 days, pulmonary hypersecretion ≥ 60 mm Hg, immediate surgery, other than coronary artery by-pass grafting (CABG); 3 points for: reoperation, active infective endocarditis, sudden cardiac arrest in the ventricular tachycardia, or ventricular fibrillation, EF < 30%, surgery on the thoracic aorta.

Based on the above calculations, the risk of death can be divided into: small (0.8%), when the patient scores 0–2 points, average (3.0%) – 3–5 points, and large (11.2%) ≥ 6 points (Table I–IV).

Table I

Characteristics of study group

Table II

Preoperative risk factors and kind of operations depending on gender

Table III

Preoperative risk factors and kind of operations depending on VES points

Table IV

Preoperative risk factors and kind of operations depending on ES points

Statistical analysis

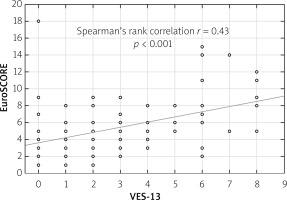

The following data from the patient’s disease history were used in this analysis: age, sex, type of surgery, type of postoperative complications, and time of postoperative hospitalization of the patient. Data were presented using the parameters of descriptive statistics. For quantitative variables, mean values and standard deviation were determined. Nonparametric tests were implemented to compare the variables between the groups, i.e.: Wilcoxon pairs order test and Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA test. In order to show the differences in the distribution of categorical variables in the study groups, the χ2 test was applied. Differences at p < 0.05 were considered as significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistica version 8.0 software. A correlation between the VES-13 and EuroSCORE scales was calculated based on the rank order of Spearman.

Results

The average age of 100 patients was 69.47 ±6.18 years, 61% of whom were men. As for the respondents, 78% were in the age group of 60–74, 22% in the subgroup ≥ 75 years of age. The time of postoperative hospitalization varied from 5 to 54 days, and was comparable in both subgroups, 8.55 ±6.13 days on average.

The average number of points on the VES-13 scale was 3.06 ±2.25, and in the EuroSCORE scale 5.50 ±3.19. Among the older patients > 75 years old, a significantly higher average VES-score was observed (4.32 ±2.6 vs. 2.707 ±2.02) and EURO (8.09 ±3.02 vs. 4.77 ±2.83). Based on the statistical analysis, it was observed that significantly more postoperative complications occurred in patients who obtained ≥ 6 points in VES-13 and EuroSCORE scales. The most frequent postoperative complication we observed was atrial fibrillation, which did not occur before the operation. Among postoperative complications most often there were the following: death (5%), delirium (3.64%), bleeding (3.54%), stroke (3.54%), renal failure (3.32%), pacemaker implantation (3.28%), difficult healing of the wound (2.64%), intestinal ischemia (2.56%) (Table V).

Table V

Postoperative complications

As for other complications such as perioperative myocardial infarction, pericardial fluid or pleural fluid, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) implantation occurred sporadically.

Spearman’s rank correlation between the VES-13 and EuroSCORE scales is 0.43, which means a moderate correlation between the scales (Figure 1).

Discussion

In Poland, the VES-13 scale has not been widely used so far, in contrast to the EuroSCORE scale, which is widespread in cardiac surgery. Therefore, the question arises whether patients > 60 years old admitted for cardiac surgery should be assessed only with the help of the VES-13 scale, in which there were 6 questions concerning physical fitness, and 5 questions concerning functional fitness.

In the case of the VES-13 scale applied, the ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve was determined to establish the optimal cut-off point for making the diagnostic decisions. Scoring at the level of 6 points or more allowed the patients to be recognized as susceptible to a deterioration of fitness. Since the introduction of the VES-13 scale, its usefulness has been verified in various populations of patients.

In original studies by Saliba et al. [7], at least 6 points of this scale were found in as many as 32% of those surveyed in the American population. This group was characterized by a 4.2-fold greater risk of death or deterioration of functional capacity in the period of 2 years in comparison with the persons who obtained less than 6 points on the VES-13 scale. Subsequent observations have also confirmed a relationship between VES-13 score and prognosis. In the study of Min et al., in the outpatient population over 65 years of age, the total risk of death and functional impairment over the average 11 months increased from 23% at 6 points to 60% at 10 points obtained on this scale [8, 9]. With an increasing number of points on the VES-13 scale, the specificity also increased, but the scale sensitivity decreased both for predicting a deterioration of physical fitness and the assessment of death risk [10]. A VES-13 scale score of 6 points or more predicts a deterioration in performance with a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 54%. The sensitivity was 87% and the specificity 37% for predicting the risk of death.

These researchers have also shown that the risk of functional impairment is multiplied by 18%, and death by 50% for each point of the score increase in this scale. For patients over 74 years of age, in their follow-up of 4.5 years on average, they also proved that the total risk of death and deterioration was 1.37, and the relative risk of death was 1.23 for each additional point on the VES-13 scale [10]. In the present study, a too short observation time does not allow for a wider assessment of a relationship between the result on a scale and the risk of death. In the Irish population, McGee et al. demonstrated that the VES-13 scale may be useful in predicting and planning medical care provision for older patients [11]. However, prospective observations indicate that the VES-13 score does not affect the quality of the care that a patient receives, which turned out to be dependent mainly on multi-robustness [12].

It is believed that the VES-13 scale, together with a shortened battery of physical condition, may be a useful screening procedure in the primary care to establish a clinical and rehabilitation plan for elderly patients [13]. The VES-13 scale was used less frequently with the hospitalized patients but proved equally useful. In the trauma department, the VES-13 score together with the severity of the injury proved to be useful in predicting complications and death risk among older patients, and in identifying the candidates for additional geriatric care [14]. The VES-13 scale was one of the elements of geriatric evaluation of an elderly patient admitted to the intensive care unit which led to a faster diagnosis of functional problems and influenced the care procedures being used [15]. The VES-13 scale is also widely recommended by oncological societies for an initial selection of elderly patients with cancer in order to qualify for a full geriatric assessment and a further decision on the choice of a therapeutic strategy [16]. In cross-sectional studies of older neoplastic patients, both hospitalized and outpatient, the prognostic value was comparable to full COG with sensitivity from 61% to 88%, specificity from 62% to 86% [17–19].

In the world medical literature, the results of research on the usefulness of the VES-13 scale in the prediction of perioperative complications in cardiac surgery have not been reported so far. On the basis of performed analyses of perioperative complications among seniors operated in the Silesian Center for Heart Diseases in Zabrze, the introduction of the VES-13 scale is particularly important for the assessment of patients in the middle and old age range due to the increasing psycho-motor problems that result from the weakness syndrome. This scale complements the EuroSCORE scale. The tests show a moderate correlation between the VES-13 scales and EuroSCORE; these scales cannot be used interchangeably.