Introduction

Patients with cancer have a high incidence of thrombosis, such as venous thromboembolism (VTE) and arterial thromboembolism (ATE) [1, 2]. However, cancer patients with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) might have asymptomatic DVT found in lower extremity veins, as well as symptomatic DVT. Thrombosis in cancer patients is often treated as cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT). Many researchers interpret CAT to include VTE (comprising DVT and pulmonary embolism – PE), arterial thrombosis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation that manifests in individuals diagnosed with cancer [1, 2]. On the other hand, there are reports describing CAT as only cancer-associated VTE [3, 4], or VTE and PE [5]. Furthermore, in recent years, some studies have also included thrombosis occurring in connection with cancer treatment as CAT [6]. As described, the definition of CAT is not necessarily uniform [1–6] and caution is required. Moreover, the frequency of CAT is attracting attention from the perspectives of improving detection methods, improving the life prognosis of cancer patients, and developing treatments for thrombosis. The frequency of occurrence varies depending on the study, with previous reports stating that VTE occurs in 15–30% of cancer patients [7–9], and ATE develops in 1–4.7% of cancer patients [10, 11]. These frequency differences are presumed to be related to different definitions of CAT and the inclusion or exclusion of asymptomatic CAT.

The incidence of CAT, whether VTE or ATE, is higher in lung cancer patients than in patients with other cancers [3]. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which accounts for the majority of lung cancers, the discovery of driver genes and the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeting these genes have led to a dramatic improvement in treatment outcomes [12]. Among these driver genes, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation and EGFR-TKIs were the first to be clinically applied, and they appeared in clinical practice in the 2000s. Survival rates for patients with this mutation have improved significantly with this therapeutic revolution [13, 14]. However, even in patients with driver genes and corresponding TKIs, the prognosis remains poor for patients with severe comorbidities [15]. Very recently, a study has reported complications in NSCLC patients treated with EGFR-TKIs [16]. Interestingly, this report showed that TKI use was associated with increased hazard ratios of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, such as heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and ischemic stroke [16]. While searching for patients for this report, we found NSCLC patients at our institutions with EGFR mutations who developed CATs [17]. Indeed, several case reports of EGFR-positive NSCLC patients who developed CATs have been published [17–23]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports investigating the frequency of CATs in EGFR-positive NSCLC patients. In addition, there have been no reports that clearly show whether EGFR-positive NSCLC patients have a higher incidence of CATs than EGFR-negative patients.

Based on this background, we conducted a multi-center retrospective study with the purposes of clarifying whether EGFR-positive patients have a higher incidence of CATs than EGFR-negative patients, and whether patients who develop CATs have a significantly poorer survival.

Material and methods

This retrospective study was a medical record review of all consecutive patients pathologically diagnosed with NSCLC at six medical institutions affiliated with the University of Tsukuba from April 2009 to March 2025. Pathological diagnosis was based on the World Health Organisation classification. All patients underwent tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) classification [24] using head computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scans, 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography/CT, and ultrasonography and/or CT of the abdomen prior to initiation of the therapy. The following demographic information was extracted from the patients’ medical records at the time of NSCLC diagnosis: age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS), histology, and stage. Overall survival (OS) of the patients was calculated as the time from the diagnosis of NSCLC to the date of an event or the latest follow-up contact. EGFR gene diagnosis was performed using one of the following diagnostic methods: Cobas EGFR Mutation Test, Oncomine Dx Target Test, or Foundation One test.

Since the definition of CAT is not uniform [1–6], in this study, we defined CAT as any of the following:

symptomatic venous or arterial thrombosis caused by cancer;

asymptomatic venous or arterial thrombosis detected by brain contrast CT or MRI;

asymptomatic venous or arterial thrombosis in the lungs or other organs detected by contrast-enhanced chest or abdominal CT.

Brain contrast CT or MRI examinations, and chest and abdominal contrast CT were performed, in principle, at the time of lung cancer diagnosis, and every 2–3 months to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment and to assess progression, even if there was no change in symptoms. These contrast CTs were also performed when symptoms worsened or new symptoms appeared.

However, in this study, asymptomatic lower limb venous thrombosis detected by ultrasound examination was not included as a CAT. Disseminated intravascular coagulation was also excluded. Lacunar infarctions (small vessel occlusion) or atherothrombotic brain infarctions (large artery atherosclerosis) related to hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes were completely excluded. For brain lesions, brain MRI was essential to differentiate between these lesions, and diagnosis was made taking into account the location, shape, and size of the lesion. It can be difficult to differentiate brain metastases, especially oligometastasis [25], from vascular disorders, and in such cases, MRI was used to differentiate between these conditions. Ischemic vascular disorders caused by arrhythmia, such as atrial fibrillation or heart diseases, which could cause thromboembolism, including valvular heart disease, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and cardiomyopathy, were also not included as CATs. In addition, patients with vascular or arterial ischemic disease that occurred more than one year before their lung cancer diagnosis were excluded from the diagnosis of CAT. We also confirmed whether the time of onset of CAT occurred before lung cancer diagnosis or during lung cancer treatment.

The χ2 test and Mann-Whitney U test were used for statistical comparison between groups. To ensure that the group of EGFR-positive patients and EGFR-negative patients were as similar as possible, we used propensity score matching. Selected covariates included sex, PS, age and clinical stage. Matching was carried out using a ratio of 1 : 1 or 1 : 4 and a calliper distance of 0.030, without replacement. Using the generalized Wilcoxon test and Cox’s proportional hazard model, survival probability was estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method. A multivariate analysis was carried out with the significant factors identified in the univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis analysed factors with p-values less than 0.2 by univariate analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results

Characteristics of patients and incidence rate of cancer-associated thrombosis

During the survey period, clinical information on a total of 1,891 patients, including 381 EGFR-positive and 1,510 EGFR-negative patients, was collected. The clinical backgrounds of these patients are shown in Table 1. Significant differences in gender, PS, histological type, and clinical stage were confirmed between the two groups of patients. Among the 1,891 patients with NSCLC, 37 patients (2.0%) developed CATs. The incidence rate of CATs under these conditions with different clinical background factors was 4.2% (16 of 381 patients) in EGFR-positive patients, and all of them had brain CATs. On the other hand, 1.4% (21 of 1,510) of EGFR-negative patients had CATs, 19 brain CATs and two pulmonary CATs. Both EGFR-positive and EGFR-negative patients who developed CATs were in advanced stages, and none underwent surgical resection, and thus none developed CATs postoperatively. We first confirmed that there was a significant difference in the incidence of CATs between the EGFR-positive and EGFR-negative patients without matching the two groups of patients (p = 0.001) (Table 1). Then, we matched the clinical backgrounds of these two groups of patients and compared CATs. Table 2 shows the comparison between EGFR-positive and EGFR-negative patients after propensity matching for the clinical backgrounds which differed between the two groups. The incidence of CATs was significantly different between the two groups, with 3.9% (13 of 333) in EGFR-positive patients and 0.9% (3 of 333) in EGFR-negative patients (p = 0.011).

Table 1

Comparison of clinical features in patients with or without epidermal growth factor receptor

Table 2

Comparison of clinical features in non-small cell lung cancer patients with or without epidermal growth factor receptor mutation after performing propensity matching

Logistic regression analysis was performed to examine whether the mutation frequency for EGFR was a significant risk factor for CATs. The results are shown in Table 3. Clinical stage IV and the mutation frequency for EGFR were both risk factors for developing CATs.

Table 3

Logistic regression analysis in epidermal growth factor receptor-positive and -negative patients

Clinical characteristics of patients who developed cancer-associated thrombosis

A comparison was made between the 16 EGFR-positive patients and 21 EGFR-negative patients who developed CATs. The results are shown in Table 4. No significant differences in age, gender, PS, histology, or clinical stage were observed between these patients.

Table 4

Comparison of epidermal growth factor receptor-positive and -negative non-small cell lung cancer patients who developed cancer-associated thromboses

The EGFR mutation types of the 16 EGFR-positive patients who developed CATs were Exon 19 deletion in seven patients and Exon 21 L858R in nine patients, with no other types of mutations observed. In both groups, two-thirds of patients developed CATs within one month of lung cancer diagnosis (Table 4).

Survival in patients who did and did not develop cancer-associated thrombosis

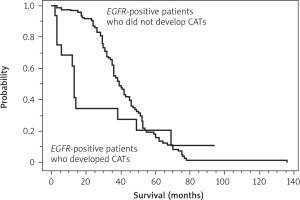

As shown in Table 5 A, the clinical features of the 16 EGFR- positive patients who developed CATs and the 365 EGFR- positive patients who did not develop CATs were different. Therefore, propensity matching was performed to remove differences in clinical features (Table 5 B). After propensity matching of these two groups of patients, we compared OS from the start of anticancer treatment and found a significant difference between the groups (median survival, 13 months vs. 39 months, with and without CATs, respectively; p = 0.003) (Figure 1). This result indicated that the development of CATs was associated with shorter OS in EGFR-positive patients.

Table 5A

Comparison before propensity matching of clinical characteristics in epidermal growth factor receptor-positive patients with or without cancer-associated thromboses

Table 5B

Comparison after propensity matching of clinical characteristics in epidermal growth factor receptor-positive patients with or without cancer-associated thromboses

Figure 1

Comparison of the overall survival (OS) from the start of anticancer treatment between the 16 epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-positive patients who developed cancer-associated thromboses (CATs) and the propensity matched 96 EGFR-positive patients who did not develop CATs

There was a significant difference in OS between the two groups of patients (median OS, 13 months vs. 39 months, with and without CATs, respectively; p = 0.003). This result indicates that the development of CATs is associated with shorter OS in EGFR-positive patients. OS – overall survival, EGFR – epidermal growth factor receptor, CATs – cancerassociated thromboses

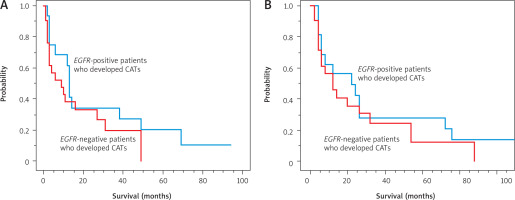

Next, we compared the survival of the 16 EGFR-positive patients and 21 EGFR-negative patients who developed CATs. As shown in Table 4, all patients in both these groups had advanced NSCLC. As there were no differences in clinical features between the two groups, we investigated OS from the start of anticancer treatment and from the onset of CATs. From the start of anticancer treatment, there was no significant difference in OS between the two groups (median survival, 13 months vs. 9 months, EGFR-positive and EGFR-negative, respectively; p = 0.236) (Figure 2 A). For survival time from the onset of CATs, there was also no significant difference between groups (11 months vs. 6 months, EGFR-positive and EGFR-negative, respectively; p = 0.447) (Figure 2 B).

Figure 2

Comparison of the overall survival (OS) from the start of anticancer treatment between the 16 epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-positive patients and 21 EGFR-negative patients who developed cancer-associated thromboses (CATs). There was no significant difference in OS between these two groups (median OS, 13 months vs. 9 months, EGFR-positive and EGFR-negative, respectively; p = 0.236) (A), comparison of the OS from the onset of CATs between the 16 EGFR-positive patients and 21 EGFR-negative patients who developed CATs (B)

There was no significant difference in OS between these two groups (median OS, 11 months vs. 6 months, EGFR-positive and EGFR-negative, respectively; p = 0.447). OS – overall survival, EGFR – epidermal growth factor receptor, CATs – cancer-associated thromboses

Discussion

The summary of the results of this study are as follows. First, among 1,891 patients with NSCLC, 37 patients (2.0%) developed CATs. Of the 381 EGFR-positive patients, 16 (4.2%) developed CATs. Second, the incidence of CATs in EGFR- negative patients was 1.4% (21 of 1,501 patients). When comparing EGFR-positive and EGFR-negative patients after propensity matching for different clinical backgrounds, the incidence of CATs was significantly different between the groups – 3.9% (13 of 333) in EGFR-positive patients and 0.9% (3 of 333) in EGFR-negative patients. Therefore, the risk of developing CATs was higher in EGFR-positive patients than in EGFR-negative patients. Third, in EGFR-positive patients, the most common time to develop CATs was at the time of lung cancer diagnosis, but there were some patients who developed CATs during second-line treatment or later when EGFR-TKIs were no longer effective. Fourth, we found that the development of CATs shortens OS in EGFR-positive patients, meaning that the development of CATs impairs the long survival expected in EGFR-positive patients.

It is generally accepted that the incidence of thrombosis, including VTE and ATE, in patients with cancer is higher than in individuals without cancer [26–29]. Multiple mechanisms are assumed to be the cause [26–29], but regardless of the mechanism, in some patients, once CAT develops, their general condition deteriorates, making active treatment difficult. As a result, survival time may be shortened. In addition to elucidating the mechanism of CAT onset, it is important to treat CAT at the same time as treating the cancer itself. Many studies conducted on ischemic disorders in cancer patients have investigated VTE, including venous thrombosis, PE, and migratory superficial thrombophlebitis [16, 30–38] and reported widely varying incidences of CAT, of 5.3–35.8% [16, 30–38]. The difference in the frequency of CATs is largely due to the definition of CAT in each study, i.e., whether only VTE is included or whether ATE and PE are also included. The results are also likely to be significantly different depending on whether CAT also includes asymptomatic VTE detected by lower limb ultrasound. In addition, results might vary depending on how long CATs are observed, so caution in this regard is also required. Moreover, when discussing the relationship between EGFR mutation and the development of CATs, it is necessary to confirm the mutation frequency for EGFR itself in NSCLC. The mutation frequency for EGFR is higher in East Asians (30–50%) than in Caucasians (10–15%) and this should be taken into consideration when discussing the frequency of CATs [25].

To date, there have been several reports regarding the relationship between EGFR gene mutation and CAT [16, 31–36, 39, 40]. With the exception of a report by Wang et al. [36], in which VTE was observed in 60.6% of 117 resected EGFR-positive lung cancer patients, the incidence of VTE is 6.4–14.4% [31, 34, 35]. In a report by Verso et al. investigating only PE, 21.6% (5 of 31) of EGFR-positive patients developed PE [33]. In a study by Roopkumar et al. including 165 EGFR-positive patients, the incidence of DVT, PE, visceral vein thrombosis and arterial events was 8.8% [39]. Two studies used a background factor matching method, but only examined VTE, reporting an incidence of VTE of 6.4% and 14.4%, respectively [31, 34]. There is currently no consensus on whether EGFR mutation is a risk factor for CATs, with some reports showing that it is a risk factor [16, 31, 33, 35, 36], while others report no risk [32, 34, 39].

Our study reported results from 381 patients with positive EGFR mutations, which is a greater number than in any previous study. The incidence of CAT was 3.9%, but would have been higher if asymptomatic DVT had been included as a CAT. In addition, we showed that EGFR mutation frequency is a risk factor for developing CATs, however, future research with a larger number of patients and detailed clinical information is required to clarify the association between EGFR mutation and the development of CATs. The identification of markers to help predict the onset of thromboembolism are also needed [40, 41], and further developments in this regard are expected.

Currently, heparin administration is considered appropriate for the treatment of VTE and CAT [42, 43], but no standard therapy has been established. Heparin administration is basically intravenous administration and is not suitable for home treatment. Intermittent subcutaneous injections of heparin and low molecular weight heparin are considered to be the most common standard treatments for CATs; all the patients in our study who developed CAT were treated appropriately with these drugs. Recently, direct oral anticoagulants are being administered to some patients [44], but there is currently insufficient evidence and possible publication bias in this area. Clinical trial results and large-scale data from clinical practice would provide important information leading towards the establishment of a standard therapy in the future.

While providing some valuable findings, this study also has some limitations. First, at present, no definition or definitive diagnostic method for CAT has been established, providing us with difficult methodological conditions and making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Second, this was a retrospective study. Although the survey period was long, it was not possible to standardize the survey period among the institutions surveyed. Although we were able to investigate OS, we were unable to survey quality of life. Third, in this study, propensity matching that included vascular risk factors, such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, could not be performed as it was a multicentre study and it was not clear how the degree and duration of these factors were related to the onset of CATs. Finally, novel gene mutations were discovered during the study period, and specific TKIs became available to patients who were positive for these mutations. However, the genetic mutations investigated at each facility were not consistent and were dependent on the time of the investigation. Patients who were positive for mutations other than EGFR, such as the anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion gene [45], were included in the EGFR-negative group in this study, but it was unclear how this affected the results. A future issue is how to reflect differences in the mutation frequency for EGFR between races when comparing results.

Conclusions

Some NSCLC patients develop not only VTE but also ATE, and it is feared that the prognosis of some of these patients will be poor. Therefore, it is important to understand all CATs. Among NSCLC patients, EGFR-positive patients are currently treated with TKIs and are expected to have a certain long-term prognosis. However, there is concern that OS might be shortened if CATs develop, as shown in our study. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the possible development of CATs in EGFR-positive patients. The establishment of better treatments for both CATs and lung cancer is highly desirable, as it should provide a longer survival for NSCLC patients who develop CATs.