Introduction

Cannabinoids are a group of biologically active organic compounds isolated from cannabis (Cannabis sativa) that act via CB1 (CB1r) and CB2 (CB2r) receptors. Cannabis contains more than 560 compounds, of which more than 100 are substances classified as cannabinoids, mainly the psychoactive Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and the non-psychoactive cannabinol (CBN) and cannabidiol (CBD) [1, 2]. Research into the identification of receptors for cannabinoids in the nervous system has led to the discovery of CB1r and then CB2r on splenic infiltrating macrophages, as well as the TRPV1, GPR55, and CPR119 receptors [3, 4]. The search for endogenous ligands for these receptors resulted in the discovery of anandamide (AEA), 2-arachidonoylo-glycerol (2-AG), and palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) [5]. The endocannabinoid system comprises cannabinoid receptors (mainly CB1r and CB2r), endogenous lipid substances that act as ligands for these receptors, and molecules that regulate endocannabinoid synthesis and degradation. Endocannabinoid mediators are not accumulated in cells but are synthesized de novo from lipid precursors in cell membranes and released in response to specific stimuli. Studies indicate that the transporter of endocannabinoids in the liver is the organ-specific fatty acid binding protein type 1 (FABP-1) [6].

Expression of the cannabinoid CB1r predominates mainly in the central nervous system. Activation of CB1r regulates learning, perception, motor function, and behaviour. CB1 receptors are also found peripherally on endothelial cells, adipocytes, intestinal cells and hepatic cells (hepatocytes, stellate cells, and liver endothelial cells). Cannabinoid transmission through CB1r stimulation regulates the intake of high-energy foods and alcohol, energy homeostasis in the body, and lipogenesis in the liver.

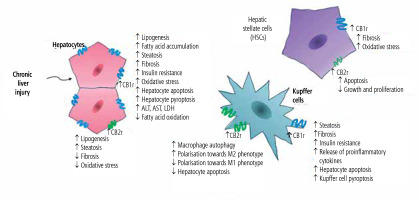

Under physiological conditions, CB2r expression is significantly lower than CB1r expression. The CB2r is commonly found on monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, B-cells, CD8 and CD4 cells, NK cells in the peripheral blood, tonsils, spleen, and testes. Its expression on hepatocytes in physiological conditions is scarce [7]. In the liver, the predominant cannabinoid receptor is CB1r, while CB2r expression has been confirmed primarily in Kupffer and stellate cells. However, it was reported that liver injury may contribute to the increase of CB2r expression on hepatocytes [8]. The summarized effects of activation of hepatic cannabinoid receptors CB1r and CB2r in chronic liver diseases are presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1

Summarized effects of activation of hepatic cannabinoid receptors CB1r and CB2r in chronic liver diseases

The endocannabinoid system is one of the mechanisms regulating immune system activity, mainly through stimulation of CB2r commonly found on various immune cells. The effect of CB2r activation on immune cells is an immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive action involving inhibition of T-cell, neutrophil, and dendritic cell migration, suppression of the production of certain pro-inflammatory cytokines, T-cell activation, and suppression of humoral responses. Hence, activation of the endocannabinoid system via phytocannabinoids, endocannabinoids, or synthetic CB2r agonists attenuates antimicrobial immunity, weakens the inflammatory reaction associated with the Th17 response, and promotes the Treg phenotype, which may be important in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, but also might impair immune control in carcinogenesis [9]. In addition, abnormalities in endocannabinoid transmission occur in the course of various nervous system diseases, metabolic disorders, immune response disorders (allergy and hypersensitivity), cardiovascular and gastrointestinal diseases, and carcinogenesis [10].

Effect of cannabinoids on liver fibrosis

Numerous reports indicate elevated concentrations of endocannabinoids, especially AEA, in liver tissue during chronic liver disease. It has also been shown that excessive CB1r stimulation enhances hepatic fibrosis processes. Under physiological conditions, CB1r expression in the liver is low but increases in chronic liver inflammation. Elevated CB1r expression was found in biopsy specimens of the cirrhotic liver, predominantly in hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) during their activation and transformation into hepatic myofibroblasts in response to chronic inflammation and/or injury. The effect of CB1r inactivation on the severity of hepatic fibrosis processes has been confirmed in animal models of liver injury with carbon tetrachloride and thioacetamide and by invasively inducing hepatic cholestasis with biliary ligation. Inactivation of CB1r by pharmacological blockade or gene deletion led to a reduction in the expression of fibrogenesis markers (TGF-β1 and α-SMA) and inhibition of proliferation and increased apoptosis of hepatic myofibroblasts [11]. Furthermore, analysis of liver biopsy specimens from patients with alcoholic cirrhosis showed increased expression of CB1r only in liver tissue with advanced fibrosis [12].

The CB2r has opposite effects to CB1r in regulating hepatic fibrogenesis. Inactivation of CB2r by deletion of the encoding genes led to accelerated fibrosis in mice exposed to hepatotoxic agents [13]. In vitro studies conducted on human hepatic myofibroblasts, and activated rat hepatic stellate cells expressing CB2r showed that stimulation of CB2r with THC or the selective agonist JWH-015 in a dose-dependent manner resulted in growth inhibition or apoptosis of these cells. Endocannabinoids can affect HSCs in a receptor-independent manner. Studies indicate that AEA can directly regulate the life cycle of HSCs. In vitro stimulation of human HSCs with AEA led to cell death by necrosis, which was preceded by the formation of reactive oxygen species and an increase in intracellular Ca2+ ion concentration in HSCs [14].

Clinical studies on the effect of phytocannabinoids on liver fibrosis progression are limited. An analysis by Hézode et al. confirmed the effect of inflammatory activity ≥ A2 (METAVIR), age > 40 years at hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, hepatic steatosis, alcohol abuse, and daily cannabis use as independent risk factors for liver fibrosis progression [15].

Effect of cannabinoids on hepatic steatosis

Population-based studies have demonstrated the effect of regular cannabis exposure on the severity of hepatic steatosis and the progression of liver fibrosis in chronic HCV infection [16]. The endocannabinoid system can influence hepatic steatosis directly through endocannabinoid receptors on HSCs and indirectly through the regulation of energy homeostasis in the body. The endocannabinoid system regulates the body’s energy balance and improves appetite through CB1r stimulation in the central brain system [17] – hence the use of synthetic cannabinoids in debilitating diseases with loss of appetite or during cancer chemotherapy [18-22]. In contrast, blockade of central CB1r results in inhibition of appetite and weight loss.

The effect of peripheral CB1r stimulation is an improvement of appetite leading to a positive energy balance in the body, which results in accumulation of energy components and body fat, and increased body weight. Stimulation of peripheral CB1r increases fatty acid uptake in the liver, induces lipogenesis in adipocytes, hepatocytes and skeletal muscle, stimulates gluconeogenesis, affects adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis, decreases adiponectin production, and is involved in the development of insulin resistance [23]. A high-fat diet has been shown to increase CB1r expression in liver tissue and endocannabinoid concentrations, including AEA, potentiating metabolic homeostasis disorders; hence the use of synthetic selective cannabinoids can help restore the normal physiological balance [24]. Mice lacking CB1r are resistant to the development of obesity associated with a high-energy diet. Thus, pharmacological inactivation of CB1r with an antagonist (rimonabant/SR141716) resulted in a reduction of obesity and hepatic steatosis in laboratory rodents [25-27].

The role of CB2r in the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis is ambiguous. A study by Deveaux et al. suggested that CB2r-related messaging is involved in the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis, the development of insulin resistance, and the promotion of inflammation in the liver and adipose tissue. In mouse studies, the use of a fat-rich diet together with a CB2r agonist exacerbated hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and inflammatory activity in the liver and adipose tissue by promoting infiltration of these tissues by macrophages and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Genetic inactivation or pharmacological blockade with a CB2r antagonist led to a reduction in inflammatory activity associated with metabolic disorders [28]. Another mouse model study confirmed the beneficial effects of CB2r blockade on the regression of insulin resistance and steatosis [29]. Interestingly, in vitro studies on immortalized human hepatocytes and cells of the HepG2 lineage showed that the use of CB2r agonists increased CB1r expression and downregulated ApoB, thus contributing to lipid accumulation. Interestingly, although CB2r was present on normal immortalized human hepatocytes, the expression of the gene encoding CB2r was downregulated in the settings of steatosis induced by oleic acid [30].

While interference with and blockade of CB1r messaging appear to be justified in developing therapies for metabolic syndrome, interference with CB2r messaging is not clear-cut. A study by Denaës et al. suggested a hepatoprotective effect of CB2r relay in alcoholic steatosis and hepatitis through stimulation of macrophage autophagy and polarization to alternatively activated macrophages (M2) that protect tissues from excessive injury, but also through inhibition of classical M1 polarization that contributes to the liver damage [31].

Effect of cannabinoids on hepatic carcinogenesis

The effect of endocannabinoid transmission on carcinogenesis is inconclusive. In in vitro and in vivo studies, activation of the endocannabinoid system in the AEA-CB1r axis resulted in inhibition of tumour cell proliferation, raising therapeutic expectations [32-34]. Moreover, Vara et al. observed an in vitro carcinogenesis-inhibiting effect of CB2r activation with the selective agonist JWH-015 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell lines expressing CB1 and CB2 [35]. Similar results demonstrating inhibition of carcinogenesis in human HCC lines were obtained with MDA19, a substance with a 4-fold higher affinity to CB2r compared to CB1r. The mechanism of antitumour activity was due to the inhibition of proliferation and enhancement of apoptosis of HCC cells, reduced invasiveness of HCC, and migratory potential of tumour cells [36].

In vivo studies in a mouse model of hepatocarcinogenesis and in vitro studies in HCC cell lines demonstrated progression of tumourigenesis directly dependent on CB1r activation in HCC cells and inhibition of carcinogenesis indirectly related to the stimulation of CB2r transmission in hepatic macrophages, which secrete chemokines that recruit T lymphocytes in liver tissue. Inactivation of CB1r, the main receptor for AEA, resulted in inhibition of carcinogenesis, cell proliferation, and hepatic fibrosis. CB2r inactivation, on the other hand, inhibited migration of T-cells into HCC tissues, including CD4 cells, which are crucial for the immune control of carcinogenesis. Based on previous studies, it appears that selective CB1r antagonists may have a potential role in anti-tumour therapy for HCC while inhibiting liver fibrosis and steatosis. At the same time, the authors pointed to the absence of CB2r in HCC cells in vivo and in HCC cell lines – hence the suggestion that the anti-tumour effect of selective CB2r agonists may be indirectly due to a modulating effect on the tumour immune microenvironment [37].

The endocannabinoid system in cirrhosis

The endocannabinoid system in end-stage cirrhosis is important in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy and hemodynamic abnormalities – secondary hypertension, peripheral vasodilatation, and relative hypotension – as well as cardiomyopathy. The endocannabinoid system appears to have a neuroprotective function in hepatic encephalopathy. In a mouse model of fulminant hepatic inflammation/insufficiency, 2-AG concentrations in the brain were found to be elevated. Pharmacological stimulation of CB2r and blockade of CB1r led to a significant neurological improvement, indicating a neuroprotective effect of CB2r transmission in liver failure [38].

Numerous studies have shown the involvement of endocannabinoid relay associated with CB1r stimulation in vascular endothelial cells in the pathogenesis of vascular effects associated with cirrhosis, such as an increase in blood flow resistance across the hepatic vascular bed, vasodilatation of the arterial vessels of the visceral bed and the systemic circuit, leading to hyperdynamic circulation, hypotension, increased blood flow to the mesenteric arteries, and increased pressure in the portal system. These phenomena are often accompanied by endotoxemia due to a high blood concentration of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) synthesized by the intestinal flora in a state where passive intestinal congestion increases its passage into the blood and its elimination in the liver is impaired [39]. Scientific reports indicate that endocannabinoid secretion is stimulated by LPS circulating in the blood [30]. The association between the endocannabinoid system and cardiovascular changes in cirrhosis has been confirmed in animal model studies. It was reported that the use of a CB1r antagonist (SR141716A) led to an increase in arterial blood pressure, a reduction in visceral circulatory bed flow, and a reduction in portal vein bed pressure. Examination of peripheral blood monocytes from cirrhotic animals showed elevated levels of AEA in these cells. Intravenous administration of an isolated fraction of monocytes from cirrhotic laboratory animals or patients with known cirrhosis led to induction of hypotension, which was reversible by CB1r antagonist treatment. Furthermore, increased CB1r expression was demonstrated in hepatic arterial endothelial cells, indicating increased sensitivity to vasodilatory stimuli such as endocannabinoids synthesized by monocytes and endothelium-adherent activated thrombocytes [40].

Cirrhosis is often accompanied by cardiac complications such as cardiomyopathy with reduced responsiveness to β-adrenergic stimuli, abnormal cardiac conduction, and failure in myocardial cell contractility, while cardiac output is increased. The involvement of endocannabinoid CB1r-related transmission in the pathogenesis of cirrhosis-associated cardiomyopathy has been confirmed in animal models [41].

The endocannabinoid system as a drug target in liver disease

Studies indicate that interference with the endocannabinoid system may have beneficial effects in the treatment of a variety of diseases and conditions ranging from metabolic syndrome and obesity to alcohol, nicotine, and opiate addiction, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, conditions involving memory loss, treatment of chronic pain syndromes, as well as reduction of liver fibrosis, inhibition of carcinogenesis and therapies for chronic inflammatory and allergic diseases [42]. In chronic liver disease, the use of endocannabinoid CB1r antagonists or CB2 agonists appears to have a beneficial effect in slowing the progression of fibrosis. In an animal model of cirrhosis, the use of CB1r blockers restored normal blood pressure. In clinical trials, the beneficial effect of the CB1r antagonist rimonabant on peripheral blood lipid and glycaemic profiles, and consequently on the control of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, was confirmed. Interestingly, this treatment also influenced lifestyle modification, as smoking cessation rates were higher during rimonabant therapy [43]. Moreover, animal studies showed that the use of rimonabant reduced the preference of immature mice to consume ethanol [44]. In 2005/2006, rimonabant was the first CB1r antagonist to be registered in the USA and Europe with an indication for the treatment of obesity. In 2008/2009, the drug was withdrawn worldwide due to numerous, mainly psychiatric, and neurological, side effects associated with its action on central CB1 receptors. A consequence of this was the withdrawal from clinical trials of other CB1r antagonists that crossed the blood-brain barrier and acted on central CB1r. Currently, monlunabant, a CB1r blocker that targets peripheral receptors in the liver, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, adipose tissue, muscle, lung, kidney, and other sites, is in phase 2 clinical trials. In phase 1 clinical trials, the drug showed a favourable safety profile. Due to its appetite-reducing effect, monlunabant is undergoing phase 2 clinical trials for the treatment of obesity.

Therapeutic intervention in the endocannabinoid system is burdened with many challenges. One of these is the development of substances that act selectively on the CB1 or CB2 receptor. Another major issue in the treatment of hepatic steatosis and obesity is the production of therapeutics with a strictly peripheral effect, without affecting central nervous system function.

Summary

Studies indicate an important role of the endocannabinoid system in liver disease. These effects are summarized in Table 1. Interference with endocannabinoid transmission, through CB1r blockade or CB2 activation, appears to have a beneficial effect in slowing and even reversing hepatic fibrosis. This is of particular clinical relevance, especially since after years of searching for various substances/drugs with antifibrotic activities, to date, no therapeutic has been approved for use in clinical practice.

Table 1

Main outcomes of cannabinoid signalling in the liver

| Main outcomes and conclusions | Study design | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatic steatosis | ||

| Regular cannabis exposure is associated with the severity of hepatic steatosis in HCV infection | Population-based study | [16] |

| High-fat diet is associated with increased CB1r expression in liver tissue and endocannabinoid concentrations, potentiating metabolic homeostasis disorders The use of synthetic selective cannabinoids can help prevent physiological imbalance | Mouse model study | [24] |

| Pharmacological inactivation of CB1r with an antagonist caused reduction of obesity and hepatic steatosis | Mouse model study | [25-27] |

| CB2r agonist with fat-rich diet is associated with exacerbating hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and inflammatory activity in liver and adipose tissue | Mouse model study | [28] |

| CB2r blockade is confirmed to have beneficial effects on the regression of insulin resistance and steatosis | Mouse model study | [29] |

| CB2r signalling is associated with hepatoprotective effect in alcoholic steatosis and hepatitis | Mouse model study | [31] |

| Hepatic fibrosis | ||

| Regular cannabis exposure is associated with the progression of liver fibrosis in chronic HCV infection | Population-based study | [15] |

| Inactivation of CB1r by pharmacological blockade or gene deletion led to a reduction in the expression of TGF-β1 and α-SMA, inhibition of proliferation and increased apoptosis of hepatic myofibroblasts | In vitro and mouse model study | [11] |

| Increased expression of CB1r was confirmed in liver tissue with advanced fibrosis in alcoholic liver disease | In vitro and mouse model study | [12] |

| Inactivation of CB2r by deletion of the encoding genes led to accelerated fibrosis in mice exposed to hepatotoxic agents | Mouse model study | [13] |

| Stimulation of CB2r on HSCs with THC or the selective agonist JWH-015 in a dose-dependent manner resulted in a growth inhibition or apoptosis of these cells | In vitro study | [14] |

The therapeutic use of cannabinoids has been controversial in recent times. It appears that synthetic cannabinoids with selective agonist or antagonist effects may be employed as therapeutic agents. The main problem associated with their use appears to be their central psychoactive effects. The use of synthetic cannabinoids or isolated specific phytocannabinoids as narcotics or ‘therapeutic’ agents has been a growing social and health problem in recent years, especially considering the legalization of ‘medical marijuana’. This is in line with the pro-natural ‘pro-cannabinoid’ trends in alternative medicine. Patients, including those with liver disease, are turning to isolated phytocannabinoids available on the internet, often unaware of their mechanisms of action. It should be emphasized that interference with endocannabinoid transmission can be an attractive therapeutic target, but only compounds that act selectively on peripherally located receptors can find a well-established place as therapeutic agents in the treatment of liver disease.