Introduction

ChatGPT (Chat Generative Pre-Trained Transformer) was released to the public as a prototype on November 30, 2022. Developed by OpenAI, it uses artificial intelligence (AI) to generate responses based on large datasets, employing a technique known as “reinforcement learning” with human feedback [1].

Currently, large language models (LLMs), and particularly ChatGPT, due to their capabilities, are being used in various fields, including medical education. The use of this tool holds potential for both physicians and medical students, especially when learning specific topics or resolving substantive doubts. ChatGPT enables significantly faster access to a synthetic response containing key information compared to traditional methods such as consulting medical literature or conducting internet searches. Moreover, the tool facilitates efficient data analysis and supports the process of drawing conclusions. By using recognition systems, the model can also interpret the context of a query and provide example solutions [2]. It may further assist in classifying medical conditions and developing treatment plans, but due to the risk of justifying results with fabricated scientific articles or providing incorrect solutions, the usage of this technology must be strictly monitored [3, 4].

LLMs also constitute a promising tool for specialists working in rapidly evolving and dynamic fields, such as thoracic surgery. In order to provide the best possible treatment outcomes, thoracic surgeons must continuously expand their knowledge and skills. ChatGPT may become a valuable supplementary tool for acquiring information in this domain. However, one of its limitations is its inability to assess crucial aspects of surgical competence and its potential to generate misleading responses [5].

Aim

The aim of the authors of this publication is to assess the effectiveness of the ChatGPT-3.5 model by testing the accuracy of this tool in formulating correct answers to questions included in the test portion of the National Specialist Examination (PES) in thoracic surgery.

The test portion of the PES consists of 120 questions, each containing one correct answer and four incorrect options. To obtain the title of medical specialist in the field of thoracic surgery, a minimum of 60% correct responses is required. The purpose of these questions is not only to assess theoretical knowledge but also to test logical thinking and reasoning skills [6].

Material and methods

Examination and questions

The analysis of the capabilities of language models in the field of thoracic surgery was conducted based on questions from the autumn 2015 session of the PES. A total of 120 test-based examination questions were included in the study, covering a broad range of topics in thoracic surgery – from anatomical and pathophysiological foundations to practical aspects of diagnosis, surgical treatment, and postoperative care.

As part of the study, each question, preceded by a properly prepared introductory content, was evaluated five times in independent sessions. The introductory content was intended to clearly define the rules and structure of the test, which allowed for the replication of examination conditions in the single-choice format requiring the selection of the most accurate answer. An answer was considered correct if it was selected in at least 3 out of 5 independent test sessions.

Additionally, an indicator of the most probable answer was introduced, based on identifying the response most frequently selected by model across five independent sessions for each question. Based on the distribution of all responses, a confidence coefficient was calculated, defined as the ratio of the number of repetitions of the most frequently chosen answer to the total number of sessions. It is important to note that this coefficient does not reflect the model’s intrinsic epistemic confidence, but rather serves as a proxy measure of response consistency across sessions – providing an objective assessment of how reliably the model selects the same answer when queried multiple times under identical conditions.

Data collection and analysis

As part of this study, the content of questions and answers from the PES examination in thoracic surgery was obtained from a publicly available database provided by the examination center in Lodz [6], using a proprietary web scraper tool developed in Python. In addition, associated statistical data were collected, including the Human Difficulty Index based on actual responses, the Discriminatory Power Indicator, and the Point-Biserial Correlation Index. Subsequently, the questions were classified according to Bloom’s Taxonomy [7]. A two-level categorization was carried out: the first involved distinguishing between “memory questions” and “comprehension and critical thinking questions”, while the second involved theme-based classification into six subtypes: History of Medicine, Anatomy, Surgical Procedures, Pathophysiology, Clinical Proceedings, and Postoperative Complications. The final division concerned the distinction between “clinical” and “other” questions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the results was conducted using Python with the application of libraries such as pandas, scipy, statsmodels, seaborn and matplotlib.

Descriptive assessment of the analyzed material was carried out first, using basic statistics such the mean, median, standard deviation, as well as frequencies and their percentage shares.

To evaluate differences in the frequency of correct responses generated by the ChatGPT language model depending on the question category (type, subtype and clinical/other classification), Pearson’s χ2 test was applied. Differences in confidence coefficient values between individual categories were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test, while differences in confidence values between correctly and incorrectly answered question groups were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test. The relationship between the confidence coefficient of ChatGPT’s responses and the psychometric indicators of examination questions (difficulty index, discriminatory power, and point-biserial correlation) was analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

The reliability of responses provided by the model across different sessions was assessed using Fleiss’ k coefficient. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

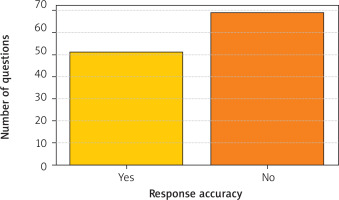

The ChatGPT-3.5 language model achieved an overall answer accuracy of 42.5%. The exact number of correct and incorrect responses is presented in Figure 1. The mean confidence coefficient was 0.67 ±0.22, with a median of 0.60. The average difficulty index of the examination questions was 0.71 ±0.35, indicating a moderate level of difficulty for the test set.

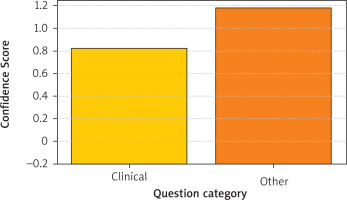

The χ2 test revealed a statistically significant difference in the frequency of correct answers between clinical and non-clinical questions (p = 0.041), as presented in Figure 2 and Table I. Additionally, the influence of question type and subtype was analyzed; no statistically significant differences were found: p = 0.255 (type) and p = 0.099 (subtype), as shown in Tables II and III.

Table I

Comparison of correct and incorrect answers by clinical vs. other

| Did ChatGPT respond correctly? | Clinical | Other |

|---|---|---|

| No | 65 | 4 |

| Yes | 41 | 10 |

Table II

Comparison of correct and incorrect answers by type

| Did ChatGPT respond correctly? | Comprehension and critical thinking question | Memory questions |

|---|---|---|

| No | 27 | 42 |

| Yes | 14 | 37 |

Table III

Comparison of correct and incorrect answers by subtype

| Did ChatGPT respond correctly? | Anatomy | Clinical proceedings | History of medicine | Pathophysiology | Postoperative complications | Surgical procedures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 5 | 13 | 0 | 19 | 4 | 28 |

| Yes | 4 | 12 | 5 | 13 | 4 | 13 |

Figure 2

Distribution of ChatGPT’s confidence coefficient depending on question classification as clinical or other (p = 0.073, Pearson’s χ2 test)

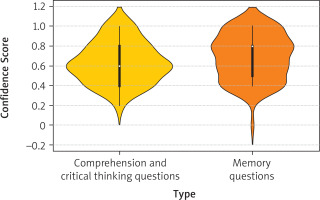

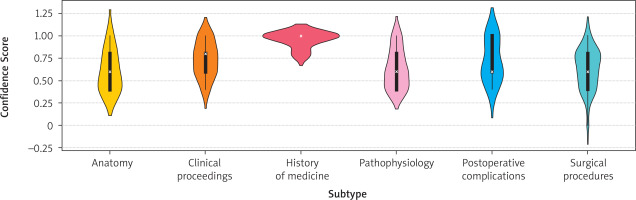

In the analysis of the confidence coefficient, the Kruskal-Wallis test revealed statistically significant differences depending on the question subtype (p = 0.015), while no significant differences were found for question type (p = 0.180) or clinical classification (p = 0.073). The distribution of the confidence coefficient by type, subtype and question classification is presented in Figures 3 and 4, respectively.

Figure 3

Distribution of ChatGPT’s confidence coefficient depending on question type (p = 0.180, Kruskal-Wallis test)

Figure 4

Relationship between confidence coefficient and question subtype (p = 0.015, Kruskal-Wallis test)

The highest confidence was observed in questions related to the history of medicine and clinical proceedings.

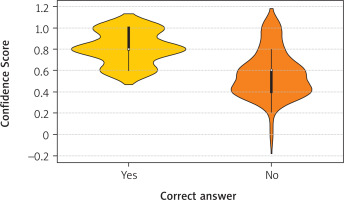

The model responded with significantly greater confidence to questions it answered correctly (mean 0.81; median 0.80) compared to those it answered incorrectly (mean 0.57; median 0.60; p < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U test), as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Relationship between confidence coefficient and answer correctness (p < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U test)

No statistically significant correlations were found between the confidence coefficient and psychometric indicators: difficulty index (r = –0.018; p = 0.847), discriminatory power (r = –0.026; p = 0.776), and point-biserial correlation (r = –0.001; p = 0.989).

The agreement between the model’s independent responses was assessed using Fleiss’ k coefficient, which had a value of 0.341, indicating a moderate level of consistency across the five test sessions.

Discussion

The PES in thoracic surgery is the mandatory final stage of the medical specialization process in Poland, intended to assess the level of theoretical knowledge and practical competence in the field of thoracic surgery. This examination, organized by the Medical Examination Center, is conducted in accordance with the specialization program approved by the Ministry of Health. Achieving the pass rate threshold (60%) is a prerequisite for obtaining the title of specialist in a particular field of medicine [8].

The tested ChatGPT-3.5 language model achieved a score of 42.5%, which corresponds to a failing result. The statistically significant difference in answer accuracy between clinical and non-clinical questions may indicate a lack of practical medical knowledge in the model’s training data. The observed relationship between answer correctness and the confidence coefficient suggests that the model exhibited higher confidence in correct responses, which may serve as an auxiliary criterion for evaluating the reliability of the generated information.

Between 2009 and 2018, 75 physicians took the PES in thoracic surgery; of these, 74 passed, resulting in a pass rate of 98.7%. Compared to these outcomes, the performance of the ChatGPT-3.5 model is significantly weaker. This highlights the superiority of clinical knowledge and professional experience held by physicians over the generalized database on which artificial intelligence relies [8].

In a study conducted by Farhat et al., the performance of the GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and Bard language models was compared using questions from the NEET 2023 entrance examination, a national medical school admission test in India. Among the three models, only GPT-4 achieved a passing score (300/700; 42.9%), outperforming GPT3.5 (145/700; 20.7%) and Bard (115/700; 16.4%). The 20.7% score obtained by ChatGPT-3.5 in the NEET examination is significantly lower than the score achieved by the same model in the PES. This discrepancy may result from the different nature of the questions: NEET primarily features tasks requiring precise factual knowledge and close alignment with answer keys, while PES questions, although more clinically advanced, may allow for more effective use of linguistic patterns and contextual reasoning by the model. In both studies, it was observed that language models perform better on theoretically oriented questions than on those requiring the application of clinical knowledge. A comparison of these analyses suggests that although LLMs demonstrate growing potential in medical education, their effectiveness strongly depends on the examination context and the level of content-specific requirements [9].

In a study by Gencer et al., the ChatGPT-3.5 model achieved a high accuracy rate (90.5%) on a theoretical thoracic surgery test designed for medical students, outperforming the average score of participants (83.3%). In contrast, in the present study involving PES-level questions, the model failed to meet the passing threshold. This difference may result from both the higher level of difficulty and the specialized nature of PES questions, as well as from the more demanding evaluation of clinical competence and the need for practical knowledge application. These results underscore that the effectiveness of language models is not universal and is highly dependent on the examination context and the depth of tested context [10].

In the analysis conducted by Kufel et al., the performance of ChatGPT-3.5 was evaluated on PES questions in radiology and imaging diagnostics. In both cases, the model failed to reach the passing threshold, achieving 52% and 42.5% accuracy, respectively. This indicates the limited usefulness of the examined version of the model in the context of specialized medical knowledge assessment. A common finding across both studies was a clear relationship between answer correctness and the model’s declared level of confidence, which may serve as a helpful indicator of the reliability of generated content. Despite differences in the subject matter of the examination, the results suggest that the effectiveness of the language models remains clearly below the level required of medical specialists [11].

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged, as they may influence the interpretation and generalizability of the results.

First, the analysis was based on a single PES (Polish National Specialty Examination) session from 2015. This restricts the number of available questions (n = 120) and potentially limits the diversity of topics assessed. Consequently, the findings may not be representative of other examination sessions or broader domains within the specialty. Second, the evaluation was conducted under standardized test conditions, without the possibility for the AI model to interact with an examiner or seek clarification – an important aspect of real-world clinical decision-making. This artificial context may not fully reflect actual clinical reasoning or communication scenarios.

Third, there was no direct comparison with the performance of human medical specialists answering the same set of questions. Without such a benchmark, it is difficult to assess the relative competence of the language model in a clinically meaningful way.

Fourth, the study tested only one language model – ChatGPT-3.5 – which is now outdated. Newer versions of large language models (e.g., GPT-4 or later) may demonstrate significantly improved performance, limiting the relevance of the current findings to the present state of AI capabilities.

Fifth, the scope of the analysis was restricted to a single medical specialty. As such, the conclusions drawn cannot be extrapolated to other medical disciplines without further investigation. Taken together, these limitations underscore the preliminary nature of the findings and the need for broader, more comparative, and updated research to better understand the role of large language models in medical education and practice.

Conclusions

In this study, the ChatGPT-3.5 language model achieved a score of 42.5% correct answers in the test component of the PES in thoracic surgery, which is significantly below the required pass rate threshold. The analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in answer accuracy between clinical and non-clinical questions, confirming that questions requiring the implementation of practical knowledge and clinical context pose a greater challenge for the ChatGPT-3.5 model.

The agreement coefficient between the five independent test sessions (Fleiss’ k = 0.341) indicates moderate response stability, which limits the reliability of the model’s answers.

Another key finding is the relationship between answer correctness and the level of confidence: when the model generated correct answers, they were associated with significantly higher confidence coefficients (p < 0.001). This may suggest the potential usefulness of this parameter as an indicator of answer accuracy.

The analysis indicates that ChatGPT-3.5 does not meet the criteria required for independently assessing specialist knowledge in the field of thoracic surgery. Further research should include a broader spectrum of medical specialties, various types of examination tasks, a larger question pool, as well as comparisons between successive model generations and solutions offered by different developers. This will help to more precisely define the potential scope of applications and the limitations of artificial intelligence in medical education and competency assessment systems.