Introduction

In recent decades there has been a very rapid increase in melanoma cases. At the same time, thanks to the emergence of immunotherapy drugs, i.e. anti-programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1), anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen (CTLA)-4 and anti-LAG-3 (lymphocyte-activation gene 3) antibodies, as well as BRAF (BRAFi) and MEK inhibitors (MEKi), many patients with disseminated melanoma have achieved long-term survival, with some even potentially achieving a cure.

Despite tremendous advances in therapy, most patients treated with immunotherapy and molecularly targeted therapy experience disease progression and the need for further lines of treatment. After the use of immunotherapy and targeted therapy, the best course of action is to enroll patients in clinical trials. If this is not possible, chemotherapy is used. To date, no chemotherapy regimen has a proven effect on prolonging overall survival (OS). However, the superiority of multidrug regimens over monotherapy has been observed in terms of increasing the objective response rate (ORR) and prolonging progression-free survival (PFS). In this paper, we present the results of the efficacy of four chemotherapy regimens used in patients with advanced melanoma at leading Polish centers, following prior immunotherapy or immunotherapy and molecularly targeted therapy, i.e. BRAFi and MEKi. Re-evaluation of the effect of chemotherapy on ORR, disease control rate (DCR), PFS and OS, despite the results known for years, is warranted due to the possible different efficacy with prior use of new generation drugs, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).

Material and methods

The study retrospectively analyzed patients with inoperable, locally advanced (stage III) and metastatic (stage IV) cutaneous melanoma. All patients included in the study had undergone chemotherapy after exhausting all available standard systemic therapies reimbursed in Poland, including anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4, combination anti-PD-1/anti-CTLA-4, as well as BRAF and MEK inhibitors. The data were collected by co-investigators from 6 oncology centers in Poland. Patients received one of the following regimens: dacarbazine (DTIC) 1000 mg/m2, paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 with carboplatin 4AUC every 2 weeks, bleomycin, DTIC, lomustine, vincristine (BOLD – bleomycin 10 mg absolute dose until lifetime dose depletion, DTIC 250 mg/m2, lomustine 40 mg/m2 and vincristine 1 mg/m2) on days 8 and 15 every 4 weeks (lomustine only d1) or cisplatin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (CVD). Cytotoxic drugs in the CVD regimen could be used in one of two protocols, i.e. cisplatin 20 mg/m2 on days 2–4, vinblastine 2 mg on days 1–5 and DTIC 1000 mg/m2 on day 1 every 3 weeks, or cisplatin 20 mg on day 1, vinblastine 2 mg on day 1 and DTIC 200 mg on day 1 every week. The dacarbazine, paclitaxel with carboplatin, BOLD and CVD regimens at absolute doses were used until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity, while the CVD regimen used per body surface area for up to 6 cycles, and treatment with DTIC alone was used if the response persisted. The treatment adhered to standard therapeutic protocols and did not constitute a medical experiment. Verbal and written consent was obtained from each patient prior to administration of the treatment. First, the patients were divided into groups according to the applied treatment. Homogeneity of such groups was compared in terms of the number of eligible patients and age, gender, stage of disease according to tumor, node, metastasis American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition and the number of metastatic organs involved, as well as in terms of BRAF mutation status and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level assessed before the chemotherapy. Subsequently, the efficacy of the applied treatment was evaluated in terms of ORR, DCR, PFS, and OS and compared according to the regimen used. The relationship between the sequence of therapy in successive lines of treatment and the type of response to them achieved and the efficacy of chemotherapy was also analyzed.

Comparisons of age and number of organs involved between the lines of treatment used were made using the Kruskal-Wallis test as the variables did not follow a normal distribution. In contrast, other categorical variables were analyzed using the β-test of independence. Progression-free survival and OS times were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator. Comparison of survival curves was conducted using the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was conducted using MedCalc for Windows, version 19.4 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). All tests were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

The study included 154 patients with advanced cutaneous melanoma. The patients received chemotherapy in the second, third or fourth line of treatment at six Polish sites between 2015–2023. Sixty-eight patients received the CVD regimen, 45 received DTIC, 23 received paclitaxel with carboplatin, and 18 received BOLD. Among the 68 receiving the CVD regimen, 16 received the regimen in appropriate doses administered every three weeks, while 39 received the modified version, in absolute doses, administered once a week.

The groups formed according to the used regimens differed statistically significantly in stage, the status of BRAF mutation, and the sequence of prior treatment. Detailed characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics of patients included in the study

[i] BOLD – bleomycin, dacarbazine, lomustine, vincristine, CTLA-4 – cytotoxic T- lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, CVD – cisplatin, vinblastine and dacarbazine, DTIC – dacarbazine, IT – immunotherapy, IT-IT – immunotherapy – immunotherapy, LDH – lactate dehydrogenase, M – men, p – p-value, PD-1 – programmed death receptor 1, TT – target therapy, ULN – upper limit of normal, W – women

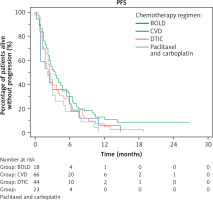

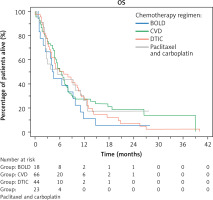

In all treated patients, the ORR was 16.88%, the clinical benefit was 38.96%, and the median PFS and OS were 2.75 [95% CI: 2.25–3.5] and 6 months [95% CI: 4.75–40], respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in ORR and DCR percentages or median PFS and OS between patients treated with different chemotherapy regimens. There was nonsignificantly higher ORR and DCR and longer median PFS for patients treated with CVD than for those receiving the other regimens. In contrast, nonsignificantly longer OS was noted for patients receiving DTIC monotherapy. Details of treatment outcomes for each regimen are shown in Table 2 as well as Figures 1, 2.

Fig. 1

Kaplan-Meier curves showing progression-free survival of pa tients undergoing chemotherapy with different regimens

BOLD – bleomycin, dacarbazine, lomustine, vincristine, CVD – cisplatin, dacar bazine, vinblastine, DTIC – dacarbazine, PFS – progression-free survival

Fig. 2

Kaplan-Meier curves showing overall survival of patients un dergoing chemotherapy with different regimens

BOLD – bleomycin, dacarbazine, lomustine, vincristine, CVD – cisplatin, dacar bazine, vinblastine, DTIC – dacarbazine OS – overall survival

Table 2

Treatment outcomes

Therapy with the CVD regimen administered every 3 weeks according to the standard protocol compared to treatment with the modified version, i.e. in absolute doses administered once a week, showed a statistically significant advantage in terms of ORR (53% vs. 13% (p = 0.001)) and DCR (63% vs. 36% (p = 0.045)). There were no statistically significant differences in PFS (4 vs. 3.5 months; p = 0.7261) and OS (6.5 vs. 6 months; p = 0.5107). The aforementioned groups differed statistically significantly in the number of patients in the respective stages. In the group of patients receiving the modified version of CVD at fixed doses, there was a higher proportion of patients in M1c and M1d stages, while there were no patients in M1a and M1b stages at all (p = 0.0001). The compared groups did not differ statistically significantly in other prognostic factors such as LDH levels, number of metastatic organs involved, and BRAF mutation status.

The conducted analyses did not show an effect of the sequence of prior therapies used on the efficacy of chemotherapy. In the groups formed according to the treatment used in the first line of treatment, i.e. PD-1 vs. PD-1 immunotherapy and CTLA-4 vs. BRAFi and MEKi, there were no statistically significant differences in the efficacy of chemotherapy in the second to fourth lines: ORR p = 0.449, DCR p = 0.851, PFS (p = 0.4040), and OS (p = 0.0644). There was also no correlation between the type of response achieved during the first and second lines of treatment and the type of response to subsequent chemotherapy.

Discussion

For many years, therapeutic strategies in the systemic treatment of advanced melanoma were limited to the use of chemotherapy. Access to ICIs and targeted therapy has initiated a new era in the treatment of melanoma patients. Despite the therapy, many patients experience disease progression, and treatment options after progression represent an unmet medical need. The efficacy, good tolerability of treatment, and appropriate management of toxicities of the new generation therapies have resulted in many patients remaining in very good functional status after disease progression.

Advances in immunology and molecular biology of cancer have led to the development of new therapies to overcome primary or secondary resistance to immunotherapy, such as vaccines (e.g. peptide-based, DNA-based, mRNA- based, vector-based) [1–3], bispecific antibodies [4], therapies using modified chimeric T-cells [5], or nanoparticles (liposomes and exosomes transporting cytotoxic drugs, antibodies or mRNA) [6]. The goal of modern oncology is to introduce new drugs for next-line therapy in melanoma patients, which will reduce the use of chemotherapy in daily clinical practice.

In the studies conducted so far in patients after ICI failure, some of the best results have been observed when anti- PD-1 was used in combination with anti-CTLA-4. This therapy has shown response rates of 8–29%, PFS of 3–5 months, and OS of 5–26 months [7–9]. A more recent combination of anti-PD1 and anti-LAG-3 antibodies showed an ORR of 11.5% and a DCR of 49% [10]. Adoptive cell therapy using tumor infiltrating lymphocytes has shown high activity in patients with ICI-resistant melanoma. The efficacy and safety of this therapy (lifileucel) were compared to ipilimumab in a multicenter phase III trial involving 168 patients with advanced melanoma after failure of prior therapy. The median PFS of patients receiving lifileucel was 7.2 months, while that of patients treated with ipilimumab was 3.1 months (hazard ratio [HR] 0.5, p < 0.001). Based on the results of this study, this drug was approved in the United States [11].

As the first systemic therapy to be introduced for the treatment of patients with advanced melanoma, chemotherapy showed little anti-tumor activity, with a low ORR and short OS. A now-historic meta-analysis of 42 clinical trials conducted in 2,100 patients with metastatic melanoma showed that median OS was 6.2 months, and one-year survival was observed in only 25.5% of patients [12].

The first cytotoxic drug to be introduced for the treatment of melanoma patients was DTIC, which, despite a 5-year survival rate of less than 10% [13], remains one of the most commonly used chemotherapeutics to this day after failure of new-generation drugs. This cytostatic has also been a comparator for modern drugs in many clinical trials, including nivolumab, vemurafenib, and dabrafenib. Fotemustine and temozolomide stand out among other drugs used. Due to their ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, there have been particularly high hopes for their use in patients with brain metastases. A meta-analysis of 26 phase I–III trials [14] showed no significant difference in terms of response rate and OS rates in patients treated with temozolomide compared to DTIC. Another treatment regimen used is a combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel. The regimen is used mainly in second-line treatment. In a phase III trial involving 823 patients with stage IV melanoma, the median OS for first-line treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel was 11.3 months (95% CI: 9.8–12.2) [15].

Multidrug regimens such as BOLD and CVD were introduced to intensify the antitumor effect. They induced a higher ORR rate, but this did not translate into prolonged OS rates and improved patient prognosis [16]. Also, a 2018 Cochrane meta-analysis of more than 1,000 patients did not confirm the superiority of polychemotherapy over mono- therapy [17].

Currently, no scientific societies recommend the use of chemotherapy as first-line therapy and, due to its limited efficacy, recommend its consideration after the failure of ICI/targeted therapy. These recommendations are mainly based on data from a period when patients were not receiving new more effective systemic treatments.

In our analysis, the effects of chemotherapy in terms of PFS and OS were not good enough in patients previously treated with ICI, and the results of therapy are similar to those observed before the era of modern therapies. Although the differences between the regimens were not statistically significant, the most favorable trend was observed for CVD chemotherapy in terms of ORR and PFS, and for DTIC in terms of OS. In addition, it was found that the CVD regimen administered every 3 weeks according to the standard protocol showed a higher ORR (53% vs. 13%; p = 0.001) and DCR (63% vs. 36%; p = 0.045) compared to the modified version treatment, with no difference in terms of PFS and OS. In this regard, the standard regimen may be considered in patients requiring rapid tumor mass reduction when malignant disease-related symptoms are present or when disease progression is dynamic.

Another retrospective multicenter study analyzed 463 me-- tastatic melanoma patients treated with chemotherapy after failure of ICI (including carboplatin + paclitaxel – 32%, DTIC – 25%, temozolomide – 15%, taxanes in monotherapy: paclitaxel and nab-paclitaxel – 9%, fotemustine – 6%) with a median PFS of 2.7 months and median OS of 7.1 months. The study reported complete remission in 0.4%, partial response in 12%, stable disease in 21% and PD in 67%. The highest activity was achieved after taxane monotherapy, with an ORR of 25%, median PFS of 3.9 months (2.1–6.2), and median OS of 7.1 months (6.5–8.0) [18]. This study, similar to our observations, shows that the role of chemotherapy at this point is limited, although there are patients who obtain a measurable benefit from its use. Among our patients, isolated survivals of up to 40 months have been reported.

Among other studies, the efficacy of chemotherapy was analyzed in patients who received prior immunotherapy compared to patients who did not receive immunotherapy. Out of 72 patients, 17 (23.6%) received DTIC after ICI, and 55 (76.3%) without prior ICI. Despite the observed higher rate of poor prognostic factors in patients pretreated with ICI, the ORR was 35.3% and 12.7%, respectively (p = 0.0007) and median PFS was 4.27 months (range 0.89–43.69) vs. 2.04 months (range 1.25–39.25; p = 0.03). Median OS and incidence of adverse events were similar in both groups [19]. Another study observed better outcomes in 35 metastatic melanoma patients receiving chemotherapy (including DTIC) when they were previously treated with ICI, with a median PFS of 5.2 months vs. 2.5 months HR 0.37 [95% CI: 0.144–0.983], p = 0.046 [20].

Another retrospective study included 71 patients receiving DTIC or CVD. Most of the patients had previously received pembrolizumab. Only 16 subjects had not previously received pembrolizumab. Median PFS was 2.3 months in the group receiving chemotherapy alone and 3.9 months in the group treated with chemotherapy after prior pembrolizumab therapy (HR 0.246, 95% CI: 0.106–0.576, p = 0.001). Median OS was also significantly longer in patients receiving prior pembrolizumab – 19.0 vs. 6.8 months (HR 0.198, 95% CI: 0.068–0.574, p = 0.003) [21].

The basis for consideration of the potentially greater activity of chemotherapy when it is administered after the failure of ICI has become the idea that chemotherapy can enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy. The effect of some cytotoxic drugs on stimulating the anti-tumor immune response is multidirectional. It has been reported that some cytotoxic drugs can directly stimulate cells of the immune system, i.e. T-lymphocytes or NK- cells, or indirectly by inhibiting immunosuppressive immune system cells such as regulatory T-cells, MDSCs (myeloid-derived suppressor cells) or by inhibiting polarization of M1-type macrophages toward M2-type [22]. In addition, some cytotoxic drugs can induce immunogenic cell death by leading to the secretion of calreticulin, adenosine triphosphate, and high mobility group box 1, which stimulate maturation, recruitment, phagocytosis, and antigen presentation by dendritic cells [23]. Dacarbazine, temozolomide and cisplatin have also been shown to induce the expression of chemokines inside the tumor and consequently enhance the recruitment of immune cells to the tumor, potentially contributing to the efficacy of immunotherapy [24]. The above observations were the basis for the evaluation in clinical trials of the association of immunotherapy, mainly anti-PD-1, with chemotherapy, which translated into the approval of nivolumab or pembrolizumab in combination with cytotoxic drugs in many indications. It cannot be ruled out that, in addition to the cytotoxic effect of chemotherapy, the prior use of ICI and its long-term effect on the immune system along with the subsequent stimulating effect of cytotoxic drugs will have a beneficial effect on the anti-tumor immune response directed against melanoma. However, this hypothesis requires confirmation in further studies.

A limitation of our analysis is the heterogeneity of groups in terms of disease stage. It is notable that in the cohorts with multidrug regimens, more than half of the patients showed poor prognostic factors (elevated LDH activity, brain metastases). Interestingly, the presence of mutations in the BRAF gene (our groups showed heterogeneity in this aspect) does not show predictive value in the evaluation of the efficacy of chemotherapy [25, 26]. The lack of a statistically significant difference between the regimens may also be due to the small number of patients in each group, although there are observations involving much larger groups of patients with similar results in terms of survival factors.

Conclusions

Chemotherapy used as second-, third- or fourth-line treatment, after prior failure of modern therapies, has minimal effect on patients’ course of melanoma and still has no proven effect on prolonging OS. So far, the superiority of any of the regimens used over the others has not been demonstrated. The observed statistically nonsignificant higher ORR and longer median PFS with the CVD regimen and OS with DTIC perhaps warrant further observation and analysis in a larger group of patients. In advanced melanoma patients, after failure of ICIs with or without BRAF/MEK inhibitors, chemotherapy should be offered. The choice of chemotherapy regimen remains dependent on the patient’s general condition, comorbidities, the need for rapid reduction of tumor masses, toxicity of chemotherapy, as well as physician and patient preference. However, it is important to keep in mind the eligibility for clinical trial treatment as a preferred option.