Introduction

Large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) represent almost 25–30% of all cases of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. The incidence of the disease worldwide is estimated at 150 000 new cases per year, and in the United States of America alone at 27 500. According to the recently published WHO-HAEM5 classification, LBCL includes: immune deficiency/dysregulation associated lymphoma, LBCL of immune-privileged sites, diffuse LBCL not otherwise specified (DLBCL-NOS), DLBCL/high grade B-cell lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 rearrangement (DLBCL/HGBL), rare B-cell lymphomas, and mediastinal grey zone lymphoma [1]. Diffuse LBCL not otherwise specified is the most common subtype of LBCL [2, 3]. The median age at diagnosis of DLBCL is 70–74 years [2]. In typical cases, the first clinical manifestation of DLBCL is progressive lymphadenopathy. In about 30% of patients, involvement of extranodal organs including the gastrointestinal tract, bones, spleen, testes, and central nervous system is observed [3, 4]. The diagnosis of specific subtypes of LBCL include the assessment of tissue biopsy material with the help of cytomorphological and immunohistochemical (Hans algorithm) methods. Differentiation of DLBCL-NOS from other types of high grade B-cell lymphomas is usually based on c-MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 gene rearrangements status evaluation (Table 1 and Fig. 1) [5, 6]. Recently, assessment of the mutational status of selected genes by the next-generation sequencing (NGS) technique along with gene expression profile (GEP) analysis has been introduced into differential diagnosis of DLBCL subtypes [7]. This strategy has allowed for a better understanding the molecular background of the disease and at least partially explains the reason for first line CHOP-R therapy failure in resistant cases with the same DLBCL diagnostic category according to cell of origin (COO), but a different molecular subtype [8]. In centers that do not have access to NGS/GEP, the evaluation of the DLBCL subtype according to the Hans algorithm, followed by evaluation of the BCL2, BCL6, and c-MYC arrangement state by the FISH technique, still remains the standard procedure.

Table 1

Cell of origin classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified according to immunocytochemistry results (Hans algorithm) [85, 86]

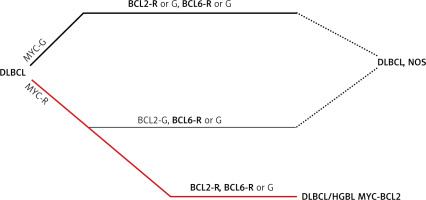

Fig. 1

Algorithm for classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas in the light of MYC, BCL2 and BCL6 rearrangement positivity [1]

BCL2 – gene, BCL6 – gene, DLBCL – diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, G – germline configuration, HGBL – high grade B-cell lymphoma, MYC – gene, R – rearrangement

Unfortunately, until today no uniform molecular classification of DLBCL- NOS has been developed. This is probably the result of the use of various diagnostic approaches in the studies carried out so far. Most of them were based on the assessment of gene rearrangements, gene mutations, copy number variations, and gene expression profiles (in various combinations) in malignant cells. The algorithm proposed by Schmitz et al. (2018) was developed based on analysis of 574 DLBCL biopsy samples with the help of exome and transcriptome sequencing, array-based DNA copy-number analysis, and targeted amplicon resequencing of 372 genes. The main objective of the study was to identify genes with recurrent aberrations. The diagnostic approach mentioned above has made it possible to identify four subtypes of DLBCL: MCD (determined by the presence of MYD88L265P and CD79B mutations), BN2 (specified by BCL6 translocations and NOTCH2 mutations), N1 (with a dominant role of NOTCH1 mutations), and EZB (characterized by the presence of BCL2 translocations and EZH2 mutations) [9]. Another recently proposed molecular classification of DLBCL by Wright et al. (prepared on the basis of the assessment of a group of 574 patients from the NCI cohort and the analysis of the co-occurrence of gene mutations, copy number variations, and BCL2/BCL6 rearrangement based on the LymphGen algorithm), by Lacy et al. (developed as a result of the evaluation of 928 unselected patients – a population-based cohort – with full clinical follow-up and 293-gene NGS analysis, with the average read depth of 500× per base), and by Chapuy et al. (based on the results of research performed in a group of 304 primary DLBCLs using whole exome sequencing [Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon 44Mb v2.0 bait set]) made it possible to distinguish six (MCD, N1, A53, BN2, ST2, EZB-Myc+ and EZB-Myc-), four (NOTCH2, BCL2, TET2/SGK1 and SOCS1/SGK1, MYD88), and five (C1–C5) different molecular DLBCL subtypes, respectively [10–12]. Analysis of the results of these studies, regardless of the methodology adopted, confirmed the existence of clear biological differences between individual DLBCL patients. However, the practical application of these molecular-cytogenetic classifications may encounter a number of difficulties. An important factor limiting the its practical application is the high degree of complexity of existing proposals and the high mutational load of each DLBCL case (7.8 driver mutations per case, and mean number of mutations in acivated B-cells (ABC) subtype and in GCB subtype 23.5 and 31, respectively) [7, 12–17]. For example, the Chapuy et al. classification mentioned above encompasses 5 clusters: C1 grouping the cases with structural variants of the BCL6 gene (observed in 72.8% of cases), mutations in the NOTCH2 gene (found in 41.8% of patients) and NF-kB pathways genes (TNFAIP3 confirmed in 51.6% of individuals); C2 including cases harboring bi-allelic inactivation of TP53 by mutations and 17p copy loss (frequency 86.8%); C3 patients harboring BCL2 mutations and BCL2 structural variants (frequency 68.4%) and frequent mutations in chromatin modifier genes – KMT2D, CREBBP and EZH2; C4 involving cases with mutations in four linker and four core histone genes, multiple immune evasion molecules (CD83, CD58, and CD70), BCR/Pi3K signaling intermediates (RHOA, GNA13, and SGK1), NF-kB modifiers (CARD11, NFKBIE, and NFKBIA) and RAS/JAK/STAT pathway members (BRAF and STAT3); and C5 grouping cases with 18q chromosomal gains with overexpression of BCL-2 protein, concordant MYD88L265P/CD79B mutations (frequency 50% and 48%, respectively) and mutations of ETV6, PIM1, GRHPR, TBL1XR1 and BTG1 present in 55%, 92.5%, 33.8%, 35% and 70%, respectively. Of note, the Chapuy et al. classification made it possible to distinguish low- and poor-risk subsets of the ABC-DLBCL category – grouped in the C1 cluster (associated with MYD88 mutations) and C5 cluster (MYD88-L265P/CD79 mutations) – and the GCB-DLBCL category: grouped in the C4 cluster and C3 cluster, respectively. Additionally, the ABC/GCB-independent group (allocated to the C2 cluster characterized by mutations and deletions of chromosome 17p) was identified [12, 18]. For comparison, according to Wright et al.’s proposed molecular classification of DLBCL, the most common molecular subtype in ABC lymphomas is MCD, in GCB lymphomas the molecular subtypes EZB and ST2, and in DLBCL-NOS the molecular subtype BN2 [10, 18, 19].

Assessment of the molecular profile of DLBCL is likely to allow individualization of the therapeutic management of DLBCL through the use of molecularly targeted drugs. Unfortunately, this method also has some limitations. It may fail in cases when the tissue biopsies do not fully capture initial intratumor genetic heterogeneity [20] or treatment-dependent and treatment-independent clonal evolution of the disease take place [21, 22]. For this reason, research has been undertaken to find a new laboratory method to study the genetic heterogeneity of cancer cells and characterize all lymphoma cells at once, regardless of the origin of the tumor cell tissues and the stage of transformation of the cancer cells. This would enable the optimization and individualization of the DLBCL treatment process depending on the genetic alteration profile and the assessment of measurable residual disease (MRD) after the end of planned treatment. One such diagnostic approach is the evaluation of free circulating DNA (cfDNA) and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) using molecular biology techniques.

Circulating cell free DNA

Free circulating DNA represents degraded DNA that move freely in body fluids. The presence of nucleic acids in the human blood plasma was first documented by Mandel et al. in 1948 [23]. Thirty-one years later, the presence of free, non-cellular DNA in the blood of cancer patients was confirmed [24]. A decade ago, advances in sequencing techniques made it possible to confirm the nature and clinical usefulness of quantitative and qualitative cfDNA evaluation in cancer patients. One such revolutionary technique was the method of deep sequencing presented by Newman et al. called cancer personalized profiling by deep sequencing (CAPP-seq) based on cfDNA evaluation by a panel consisting of biotinylated DNA oligonucleotides targeting recurrently mutated regions in different types of cancer [25].

Free circulating DNA are double-stranded and naturally fragmented DNA molecules (∼166 bp in length) released from active and apoptotic cells, during necrotic cell debris, and decaying extracellular neutrophil traps (NETosis) and extracellular vesicles [26–31]. Short, digested DNA fragments are released from macrophages into the blood during the process of phagocytosis of necrotic or apoptotic cells [32]. DNA fragments are released into the blood circulation by active secretion from living cells as well [33]. For this reason, the cfDNA could be detected at low level in the blood of healthy peoples [34–36]. It was found that cfDNA concentration in the plasma increases with age [34, 37]. Free circulating DNA has a relatively short half-life (~1– 2 hours) due to rapid elimination from plasma by the liver, kidneys and spleen [38]. One of the main cellular sources of cfDNA is hematopoietic cells [39]. The pattern of fragmentation of cfDNA has been found to be tissue specific and depends on the mechanisms of its release [40, 41]. Recently, it was also reported that a substantial proportion of cfDNA consists of single stranded “ultrashort” DNA fragments [31]. It was also documented that cfDNA maintains genetic and epigenetic signatures of the COO [42]. Another feature of cfDNA that may be used in future laboratory diagnostics is its integrity score (IS), defined as the quotient of the concentration of long and short DNA fragments in body fluids [43, 44].

The detailed characteristics of cfDNA are presented in Table 1. The molecular techniques and its characteristic used in quantitative and qualitative studies of cellular free DNA are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Circulating cell free DNA in patients with lymphomas

In most patients with cancer, the total cfDNA concentration in the blood is elevated. It is a result of the proliferation malignant cells and a high apoptosis rate of tumor cells and increased release of tumor-derived fragmented DNA into body fluids. The tumor originated cfDNA fraction is named circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) [45].

Quantification of circulating cell-free DNA in the plasma showed a positive correlation between plasma cfDNA level and stage of the neoplastic process, intensification of the inflammatory reaction, and progression of autoimmune disorders [46, 47]. The concentration of ctDNA and cfDNA in serum varies among different types of lymphoma (Table 2). In some cases of cancer, including lymphomas, the ctDNA content in the entire cfDNA pool can be very low (< 0.01%) [48].

Table 2

Circulating cell free DNA and circulating tumor DNA concentrations in the blood of healthy people and patients with classical Hodgkin disease and different types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma [38, 49–53]

Circulating tumor DNA characteristics and prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

In 2019, Kurtz et al. proposed a new prognostic model, the continuous individualized index (CIRI), which aims to predict the risk of failure of DLBCL treatment better than the currently applicable forecasting scales [54].

Continuous individualized index DLBCL includes well- established risk factors – international prognostic index (IPI), molecular COO (gene expression-based Lymph2Cx assay), interim imaging – and ctDNA variables (pretreatment ctDNA serum concentration, early molecular response (EMR), and major molecular response (MMR) and MMR) [55–57]. The results obtained from the prognostic assessment of CIRI- DLBCL in 132 patients with available ctDNA data confirmed its superiority over IPI and other risk predictors determined before treatment, the assessment of molecular response and interim positron emission tomography (PET) evaluation in predicting EFS over a period of 12–36 months. Its prognostic superiority was also clearly evident compared to IPI and other individual prognostic factors in relation to the assessment of OS at particular time points of follow-up as well as throughout the disease period [54].

Circulating tumor DNA in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

The genetic subtyping in DLBCL is based on the results of whole exome/genome sequencing, RNA sequencing, and fluorescence in situ hybridization data. Despite the large amount of genetic data generated during analysis, it was possible to prepare simplified algorithms for genetic subtyping in DLBCL (mutation-based classification) [58]. Molecular profiling of cancer cells enabled the identification of molecular and cytogenetic aberrations occurring in individual types of lymphomas. The latter facilitate the process of preparing a panel of genes which should be used in genetic subtyping of lymphoma. This strategy is now the basis for the study of individual patients using ctDNA and CAPP-Seq [59]. However, it must be taken into account that the DNA fragmentation patterns may be abnormal in cancer patients. Generally, ctDNA is shorter than non-tumor cfDNA (145bp vs. 166 bp, respectively) [57, 60–64]. It was demonstrated that the information obtained from ctDNA analysis using CAPP-seq is 90% consistent with the results of the assessment of tumor material according to the COO classification. Moreover, ctDNA analysis made it possible to detect most of the BCL2, BCL6 and c-MYC translocations, the presence of which was confirmed by the FISH technique in a routine procedure. It also turned out that ctDNA evaluation using CAPP-seq allowed the detection of other genetic changes than those present in the tumor biopsy material. This observation suggests that the assessment of the genetic profile of ctDNA better reflects the genetic background of cancer cells, regardless of where they are located [65–67]. The latter observation was confirmed by Scherer et al. and Meriranta et al. in patients with aggressive lymphoma. They documented that ctDNA measurement is more informative than tissue biopsy analysis and better reflects DLBCL tumor heterogeneity and molecular feature changes during treatment, especially when disease clonal evolution has occurred [65, 68].

In another study, Roschewski et al. analyzed serum ctDNA levels and computed tomography (CT) results in untreated DLBCL patients (n = 198) without evidence of a previous indolent histology [69]. DNA for a clonotyping study was obtained from pretreatment formalin-fixed paraffin- embedded tissue material (when tumor biopsy material was unavailable, the tumor specific clonotyping was performed using pretreatment serum samples). The genotyping of each tissue sample was based on the LymphoSIGHT method [70]. Briefly, the ctDNA level was measured using a quantitative high-throughput method, which combines amplification of immunoglobin gene segments (variable, diversity, and joining – VDJ) with NGS. The results were expressed as the number of lymphoma molecules (one tumor cell equivalent per 10 diploid genomes). This strategy allowed a tumor-specific clonotype to be identified in 126/198 (64%) of screened patients. The study confirmed that the median ctDNA level in the blood of patients with early-stage DLBCL is significantly lower than those with advanced disease stage. The study also revealed a significant association between the baseline level of ctDNA for immunoglobulin gene sequences and baseline IPI scores and serum lactate dehydrogenase activity [69]. Also, Scherer et al. using a quantitative method of ctDNA assessment documented a significantly higher level of ctDNA in patients with disease stage III + IV in comparison to patients with a less advanced disease (stage I + II) in the blood of non-treated patients with DLBCL. Moreover, the study confirmed the positive correlation between ctDNA concentrations in the blood of non-treated patients and mean metabolic tumor burden, measured from PET/CT imaging. More recent publications also indicate that the IPI, total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) measured by PET/CT, or COO subtypes have largely failed to demonstrate any utility for directing treatment in DLBCL [54, 65, 71, 72].

Lastly, Li et al. evaluated the prognostic and predictive value of ctDNA assessment before, during and after 1-line CHOP-R/CHOP-R like therapy in 73 Chinese DLBCL patients, using targeted DNA sequencing. 79.5% of them were classified as a non-GCB subtype based on Hans’ COO classification. The DNA libraries were captured with the Onco-Lym-Scan panel (Genetron Health) targeting 188 lymphoma-related genes. To improve the quality of assessment, the enriched libraries were sequenced on the NGS platform with a mean coverage depth for white blood cells control samples at least 100×, for tissue genomic DNAs 1000× and for cfDNAs 3000× after removing duplicates. Final analysis was performed in 43 primary pathologically confirmed tumors using 162 blood samples collected before, during, and after first-line therapy. The direct comparison of tumor and ctDNA genotypes among 22 paired baseline tumor/plasma samples showed the median concordance of 77.8%. Analysis of ctDNA revealed the presence of another 170 somatic mutations not detected in the tumor genomic DNA. In 51 out of 52 pre-treatment plasma samples, 951 nonsynonymous somatic mutations were detected mainly in CD79B (42%), PIM1 (42%), BTG1 (33%), KMT2D (33%), and HIST1H1E (31%) genes. The median number of mutations per sample was 14. Quantitative ctDNA assessment showed that the pretreatment ctDNA level is an independent prognostic factor for progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Moreover, in the multivariate analysis, higher ctDNA levels after two therapy cycles were negatively associated with PFS and OS. In the authors’ opinion, the interim assessment of the blood ctDNA clearance may be an alternative to the PET/CT method in predicting PFS and OS [73].

Circulating tumor DNA analysis and central nervous system involvement in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is observed in about 5% of DLBCL patients and in about 25% of persons with high risk of CNS involvement [74]. In most cases, the CNS infiltration has a secondary character and is a result of disease progression/resistance [75, 76]. Extremely rarely, the primary location of DLBCL is the CNS. In such cases, the neoplastic process is usually limited to the parenchyma of the brain, spinal cord, cerebrospinal fluid, leptomeninges, or eyes [52]. In 2024 Kim et al. presented data concerning analysis of ctDNA extracted from archived cerebral fluid (CSF) samples from 17 DLBCL patients with proven diagnosis of CNS involvement (14 with systemic DLBCL with secondary CNS involvement, 3 with primary CNS lymphoma). In 9/17 of cases CNS involvement was associated with isolated disease relapse. In 10/19 patients, CSF cytology was negative. In 13/17 studied cases, ctDNA was detected in CSF. In one case, library construction failed. The central nervous system symptom pattern analyzed using magnetic resonance imaging showed involvement of leptomeninges in 6, parenchyma + leptomeninges in 5, and parenchyma in 6 cases. The study was based on the developed libraries of custom hybridization probes targeting 112 genes recurrently mutated in lymphomas. The overall variant detection rate was 76%. One hundred eighty-two variants were detected in 13 patients (most commonly in KMT2D, HIST1H1, PIM1, and MYD88). The authors concluded that ctDNA sequencing of CSF samples is a feasible method for detection of CNS involvement in DLBCL patients, especially in cases showing negative result of CSF cytology [77].

The relationship between the molecular profile of the tumor and the concentration and molecular characteristics and ctDNA in plasma and CSF of patients with DLBCL were the subject of research undertaken by Wang et al. The study was conducted in a group of 67 patients with DLBCL with a high risk of CNS involvement assessed by a six-risk-factor model (five IPI factors with kidney/adrenal involvement) for CNS (CNS-IPI). Significant differences in cfDNA concentration were found between patients with CNS-IPI 0–3 and CNS-IPI 4–6. The elevated cfDNA level in CSF was confirmed in 20 DLBCL patients. According to authors, demonstrating the above relationship may indicate CNS involvement by DLBCL. The comparison of the general number of genetic aberrations detected in tumor specimens and cfDNA obtained from CSF and plasma showed consistency with 38.39% and 42.41% of cases (the corresponding number of genetic aberrations in tumor tissue, CSF and plasma was 224, 134, and 153). Forty-eight genetic aberrations were found in the CFS only. In a study, an attempt was also made to determine whether these 48 aberrations are related to the involvement of the CNS in DLBCL patients. For this purpose, the profile of gene changes in tumor tissue and CSF was additionally assessed in 10 patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL). This analysis showed a different mutation profile (except for BTG2 S31N) between patients with DLBCL at high risk of CNS involvement and patients with PCNSL. A similar comparison performed with ctDNA isolated from CSF of patients with high IPI-CNS confirmed the presence of the same 13 genetic lesions in both brain lymphoma tissue and CSF of patients with PCNSL. In the authors’ opinion, 5 of them (BTG2, PIM1, DUSP2, ETV6, and CXCR4) could be associated with CNS involvement risk in patients with DLBCL [78].

Circulating tumor DNA as a marker of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma relapse

Accumulating data suggested that monitoring of ctDNA improves early detection of DLBCL relapse. In 2015 Roschewski et al. published data concerning the usefulness of periodic monitoring of disease activity in patients in remission after 1-line treatment through CT examination and serum ctDNA assessment (quantitative high-throughput method that combines amplification of immunoglobin gene segments for IGH and IGK rearrangements with NGS). In the follow-up, seventeen out of 107 patients with DLBCL had disease relapse, with 15 of them having detectable ctDNA at the time of relapse or in the period prior to disease recurrence in CT scan. Interestingly, Cox proportional hazards model analysis showed that the hazard ratio for evident disease progression is 228 for patients with detectable vs. undetectable ctDNA. It was also found out confirmation of the presence of ctDNA in serum of DLBCL patients precedes disease recurrence with a median of 3.5 months (range 0–200). In addition, in 90 patients without relapse, ctDNA was undetectable in blood serum throughout the follow-up [69].

The direct comparison of sensitivity of different molecular techniques in the early detection of disease relapse showed the advantage of the CAPP-seq method over high-throughput sequencing of immunoglobulin (Ig) V(D)J rearrangements. The predominance of the first of these techniques has also been documented in patients with clinically overt disease recurrence. Analysis of PFS in DLBCL patients after therapy discontinuation dependently from ctDNA positivity or negativity confirmed significantly better PFS [79] in individuals remaining ctDNA negative in the follow-up [65]. The prognostic usefulness of baseline ctDNA level measurement with CAPP-seq was confirmed in a larger study including 217 patients with DLBCL across 6 different treatment centers. The study documented that baseline ctDNA is associated with both event-free survival (EFS) and OS both in patients receiving first-line treatment and in those receiving salvage therapy. Moreover, in multivariable analysis the baseline ctDNA in the blood better predicted EFS than traditional prognostic factors including COO, IPI score, or TMTV on FDG-PET scans [69]. Also, ctDNA level monitoring during initial therapy cycles seems to have practical value in patients with DLBCL. Kurtz et al. studied the dynamics of ctDNA level reduction using CAPP-seq to define the molecular response thresholds associated with survival of DLBCL patients. Interestingly, an early molecular response (EMR, defined as a 2-log reduction in ctDNA after 1 cycle of therapy) and major molecular response (MMR, defined as a 2.5-log reduction after 2 cycles of treatment) were more predictive of EFS and OS than baseline ctDNA levels, IPI, or interim PET scan results. Final analysis confirmed that both EMR and MMR were predictive of outcomes independent of the findings of PET/CT imaging [79, 80].

Quantitative and qualitative analysis of circulating tumor DNA in patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplantatio

Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is a therapeutic, potentially curative, option for patients with relapsed/resistant DLBCL. In 2020 Marryman et al. presented data confirming the potential usefulness of ctDNA clonotype analysis in the identification of patients who may not benefit from ASCT, or are at risk of post-ASCT disease relapse and would require preemptive therapy. The circulating tumor DNA was analyzed in a group of 152 patients with R/R DLBCL patients using immunoglobulin-based NGS (IgNGS). Circulating tumor DNA was isolated from autologous stem cells collection (ASC) or peripheral blood samples. The identification of patients’ specific clonotype was possible in 112 cases. Among patients with an available ASC sample, 24% (23/97) were ctDNA-positive. The 5-year PFS rates for ASC ctDNA-positive and ASC ctDNA-negative survivors were 13% and 52%, respectively. The 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse was significantly lower in the ASC ctDNA-negative than the ASC ctDNA-positive group (39 vs. 83%, respectively). Additional analysis confirmed that ASC ctDNA status was the only significant predictor of PFS in a multivariable model taking into account pre-ASCT PET scan result, number of lines of therapy, patients’ age, and primary refractoriness. Post-ASCT ctDNA analysis was possible in 56 patients with at least 3 serum samples available. Twenty-five of them relapsed. Two patients died in remission. 38% (21/52) with detectable ctDNA relapsed. Among 21 patients (38%) who had detectable ctDNA, 86% (18/21) relapsed, with a median lead time from first ctDNA detection to relapse of 52 days. In the authors’ opinion, the identification of ctDNA using IgNGS within an ASC sample is a powerful predictor of post-ASCT relapse, better than pre-ASCT PET in prediction of disease relapse, and it seems to be a strong argument for taking up alternative treatment strategies, e.g. CART cell therapy. Equally important is monitoring of the presence of ctDNA in the serum of patients after ASCT. Its detection seems to be inextricably linked to the emerging disease relapse and should be a premise for preemptive treatment initiation [81]. Quantification of ctDNA in serum of patients after 1st or 2nd line treatment does not fully enable tracking of residual disease at the molecular level, especially with regard to the occurrence of DLBCL clonal evolution features. Their finding would facilitate the decision on ASCT in high-risk patients in remission of the disease after the completion of first-line treatment. Confirmation of the presence of ctDNA would also facilitate the initiation of another form of therapy in the event of a different molecular profile of DLBCL than the initial one. The usefulness of such a strategy is suggested by the results of recently published studies. In 2024 Kim et al. analyzed the dynamics of ctDNA concentration changes in the serum of 10 patients with confirmed diagnosis of DLBCL (7 high risk according IPI), with no contraindications to ASCT, aged 50–60 years, treated with 6 cycles of CHOP-R therapy given every 21 days. Simultaneously, at the time of diagnosis and at the end of treatment, ctDNA genotyping and CAPP-seq studies were performed. The most common mutations at the time of diagnosis were NOTCH1, KMT2D, PCLO, ARID1A, RET, DDX3X, ITPKB, H1-4, CREBBP, and CARD11. Data analysis showed that changes in ctDNA mutation number did not correlate with changes in PET scan images and therapy results. In 7 patients, complete hematologic remission (CHR) was confirmed. In DLBCL high-risk patients, the appearance of new mutations in ctDNA (in most cases, PIK3CA, BRAF, TGM7, and EZH2), not present at initial evaluation, was observed after treatment discontinuation, suggesting the emergence of resistant clones. Interestingly, in 3 low-risk, mutation-positive patients who underwent ASCT, disease relapse was not observed during two years of follow-up. In the authors’ opinion, the emergence of adverse risk mutations during treatment of high-risk DLBCL patients should be considered together with well-known prognostic factors in decision making for ASCT [77].

Circulating tumor DNA in patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy

The usefulness of ctDNA monitoring after CAR T-cell therapy was confirmed by a prospective multi-institutional trial in 2021. The primary objective of the trial was to determine the dynamics and prognostic value of ctDNA measurement in LBCL patients after Axicabtagene Ciloleucel (YESCARTA) infusion [83]. Clonal VDJ gene segment ctDNA sequences were analyzed in 72 LBCL patients to characterize lymphoma-specific clonotype. The study confirmed that one week after axi-cel infusion, ctDNA was undetectable in 70% and 13% of patients with durable remission and patients with signs of disease progression, respectively. Moreover, ctDNA positivity four weeks after treatment discontinuation was associated with poor median PFS and OS (3 months vs. not reached and 19 months vs. not reached, respectively). The study also showed that ctDNA measurement allowed identification of patients at risk of developing higher-grade cytokine release syndrome and of occurrence of immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome, and that may be a useful adjunct to radiographic assessments of disease status by PET/CT after CAR T-cell treatment. A similar study was performed by Colton et al. This analysis also confirmed the usefulness ctDNA-based surveillance in patients with R/R LBCL after tisa-cel CART-cell (KYMRIAH) treatment. In 10 patients, trackable clonotypes were also established prior to CAR T-cell therapy on the basis of VDJ rearrangement studies of serum samples and archived lymphoma tissue. Response to treatment was assessed by PET/CT scan at day 90 and 365 after drug infusion. The measurable residual disease assessment at day 28 by specific clonotype identification was positive in 5 cases. Response evaluation at day 90 confirmed radiographic complete remission in 3 and progressive disease in 6 evaluated patients. Interestingly, MRD positivity was associated with short median OS and median PFS after treatment discontinuation (6.7 and 1.3 months, respectively) as well [84].

Conclusions

During the last 10 years, significant progress has been made in understanding the molecular background of DLBCL. This was made possible by the introduction of high-throughput NGS techniques and new methods for genetic material assessment using panels of the genes most frequently mutated in DLBCL. These approaches have also proven to be effective in assessing the lymphoma-derived genetic material present in circulating blood and body fluids. The assessment of the dynamics of changes in the concentration and mutation profile of ctDNA confirmed the close relationship between ctDNA concentration in the serum and response to treatment applied. Tracking changes in ctDNA serum concentration after therapy may also serve as a predictor of disease relapse, and shortened PFS and OS. This was confirmed regardless of the type of therapy performed, including immunochemotherapy, CAR T-cell therapy or autologous bone marrow transplantation. Positive predictive value of ctDNA measurement is also evident in patients with complete metabolic remission in PET/CT scan after treatment discontinuation. It also enables early detection of recurrence and clonal evolution of the disease.

For these reasons, the assessment of concentration and genetic profile of ctDNA in the body fluids of DLBCL patients is a clinically useful technique for the MRD monitoring. It independently enables a better understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease in individual cases, which may lead to personalization of DLBCL therapy in the future.