Introduction

Cancer has become a growing global health concern. Data from the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) reveals that cancer cases rose to 20 million in 2022, with approximately 10 million deaths that year [1]. In Indonesia, cancer incidence reached 396,914 cases, with 234,511 resulting in fatalities [2]. Colorectal cancer ranks third globally in incidence and second in mortality rates [1]. In Indonesia, colon and rectal cancers are among the most prevalent and fatal types [2].

Despite challenges in delivering high-quality cancer care, advancements in therapeutic modalities have helped mitigate the burden of colorectal cancers [3]. The Indonesian guidelines distinguish between the management of colon and rectal cancers [4]. Radiotherapy, a cornerstone treatment for colorectal cancer, is particularly crucial for rectal cancer compared to colon cancer [4]. Studies emphasize the importance and cost-effectiveness of radiotherapy [5, 6]. Atun et al. estimated that expanding radiotherapy services in low- and middle-income countries could save 26.9 million life years and generate USD 365.4 bi- llion [7]. However, Indonesia’s radiotherapy resources remain insufficient, meeting only 23.62–34.32% of national demand as per the 2021 Indonesian Radiation Oncology Society (IROS) assessment (unpublished).

The radiotherapy utilization rate (RUR) reflects the percentage of cancer patients receiving radiotherapy during their lifetime [8]. According to the Collaboration for Cancer Outcomes Research and Evaluation (CCORE) in 2012, the optimal RUR (oRUR) for colon cancer was 4%, while for rectal cancer, it was 60% [9]. Globally, Yap et al. found in 2013 that RUR for all cancers was 50%, with significant disparities between high-income (50%) and low- to middle-income countries (53%) due to variations in cancer types and stages [10].

Colorectal cancer presents a growing health burden worldwide, and Indonesia is no exception. Despite advancements in diagnosis and treatment, significant challenges remain within Indonesia’s healthcare system. Although radiotherapy utilization in Indonesia is rising, no RUR data for colon and rectal cancer exists. Addressing these issues is crucial for improving colorectal cancer care in Indonesia. This study aims to calculate the actual and optimal RUR for these cancers in Indonesia as part of the RCARO research project under the IAEA’s initiative to bridge radiotherapy access gaps.

Material and methods

Data collection

The study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia – Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo National General Hospital (ethical review/approval number KET-388a/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2022) before data collection. Data from 2019 was selected to avoid bias from changes in radiotherapy practices during the COVID-19 pandemic [11]. Thirty-eight of Indonesia’s 41 hospitals offering radiotherapy services participated. Secondary data collection occurred in April-September 2022.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

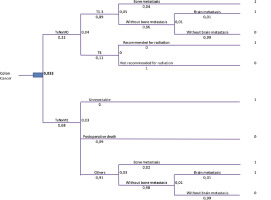

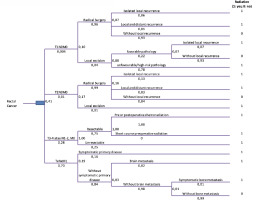

All 2019 colon and rectal cancer patients recorded in hospital cancer registries or medical records were included. No exclusions were made, but data was filtered to prevent duplicate records. The actual radiotherapy utilization rate (aRUR) was calculated as the ratio of colon and rectal cancer patients receiving radiotherapy for the first time to the total diagnosed cases in 2019 [12]. The optimal RUR was determined by adapting the CCORE 2012 tree diagram model to epidemiological data, dividing cases with evidence-based indications for radiotherapy by the total number of cases [13]. Sensitivity analyses, using GLOBOCAN 2020 and unpublished 2019 IROS survey data on radiotherapy infrastructure, refined the aRUR estimates. There are four assumptions made in this study to estimate and extrapolate so that the obtained data can represent a broader population (sensitivity analysis):

assumption 1 (cancer data estimation from 17 hospitals to 33 hospitals, based on the number of teletherapy machines): from the number of cancer patients in 17 hospitals, the number of cancer patients in 33 participating hospitals was calculated using the comparison of the number of radiation machines in 17 and 33 hospitals (30 and 50 teletherapy, IROS survey 2019, unpublished data). Then, the number of cancer patients irradiated in 33 hospitals (based on research results) was divided by the estimated number of cancer patients in 33 hospitals calculated to obtain aRUR;

assumption 2 (extrapolation of survey data from 33 hospitals to 41 hospitals, then compared to GLOBOCAN data, based on the number of teletherapy units/machines): from the number of patients irradiated in 33 hospitals (research results), the estimated number of cancer patients irradiated in 41 radiotherapy centers operational in 2019 was calculated, using the comparison of the number of radiation machines in 33 and 41 hospitals (50 and 61 teletherapy, IROS survey, unpublished data). Then, the estimated number of patients who were irradiated in 41 hospitals was compared with the GLOBOCAN 2020 data to obtain aRUR;

assumption 3 (cancer data estimation from 17 hospitals to 33 hospitals, based on patient load, IROS survey 2019): there are 17 hospitals whose data can be used to calculate aRUR. From the number of cancer patients in those 17 hospitals, the estimated number of cancer patients in the 33 participating hospitals was calculated using the comparison of patient load (total patients irradiated) in the 17 and 33 hospitals (14,556 and 22,192 patients, IROS survey 2019, unpublished data). Then, the number of cancer patients who were irradiated in 33 hospitals (based on research results) was divided by the estimated number of cancer patients in the 33 hospitals calculated to obtain aRUR;

assumption 4 (extrapolation of survey data from 33 hospitals to 41 hospitals, then compared to GLOBOCAN data, based on patient load, IROS survey 2019): from the number of patients irradiated in 33 hospitals (research results), the estimated number of cancer patients irradiated in 41 radiotherapy centers operational in 2019 was calculated using the comparison of patient load (total patients irradiated) in 33 and 41 hospitals (22,192 and 25,061 patients, IROS survey, unpublished data). Then, the estimated data of patients who were irradiated in 41 hospitals was compared with the GLOBOCAN 2020 data to obtain aRUR.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to extrapolate data from participating hospitals to all hospitals with active radiotherapy services and community settings after calculating the aRUR and oRUR. The estimation involved comparing study results with GLOBOCAN 2020 data on colon and rectal cancer patients and the 2019 IROS survey data on teletherapy (radiotherapy) machines and cancer patients.

Results

From 38 centers, questionnaires reported 3,450 cases, including 1,244 colon and 2,206 rectal cancer cases. After data filtering, 24 cases from four hospitals were excluded due to incomplete or mixed data. Among the 34 remaining hospitals, 16 used comprehensive hospital databases (reporting 3,023 cases), 17 used radiotherapy department data (307 cases), and one reported no cases in 2019. Duplicate entries (96 cases) were removed, leaving 3,330 cases (1,211 colon and 2,119 rectal cancers) for analysis. Limited data availability excluded radiotherapy-only reporting centers (25 colon and 282 rectal cancer cases) from aRUR and oRUR analyses. Table 1 highlights these exclusions and their impact on the analysis.

Based on the collected data, the oRUR for colorectal cancer in Indonesia was determined to be 26.21% (18.19–41.56%), and the aRUR was 14.9%. Thus, with a range of 21.4–65.6%, the proportion of unmet needs for colorectal cancer in Indonesia is roughly 45.5%. These numbers will be further broken down for colon and rectal cancer below.

Table 1

List of hospitals and number of colon or rectal patients (analyzed)

Colon cancer aRUR and oRUR

This study found an average oRUR for colon cancer of 3.3 (3–3.7%). As calculated from each center (Table 2), most hospitals have succeeded in meeting the optimal level of radiotherapy utilization; some even exceeded the calculated optimal needs. Overall, the percentage of unmet need for colon cancer is –60.6% (–76.7 to –43.2%).

Table 2

Colon cancer data distribution and actual/optimal radiotherapy utilization rate calculations

Rectal cancer aRUR and oRUR

From 16 radiotherapy centers with reported rectal cancer cases, oRUR was 41% (28–66%). In contrast with oRUR in colon cancer, only half of the hospital’s aRUR met their calculated oRUR. As observed in Table 3, three hospitals’ aRUR is still below optimal, with unmet needs of 55.3% at ID 1 Hospital, 52.8% at ID 7 Hospital, and 30.4% at ID 2 Hospital, respectively.

Table 3

Rectal cancer data distribution and actual/optimal radiotherapy utilization rate calculations

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to extrapolate data from participating hospitals to all hospitals with active radiotherapy services and community settings after calculating the aRUR and oRUR. The estimation involved comparing study results with GLOBOCAN 2020 data on colon and rectal cancer patients and the 2019 IROS survey data on teletherapy (radiotheraphy) machines and cancer patients.

Our findings revealed that the aRUR for rectal cancer was 4.4–22.5%, and for colon cancer, it was 0.5–5.3%. The unmet need was 19.5–93.3% for rectal cancer and –76.7% to 86.6% for colon cancer. Overall, the unmet demand for colorectal cancer was estimated to be 21.4–96.6%.

Discussion

In 2019, Indonesia had 41 active radiotherapy centers with 61 teletherapy (radiotheraphy) machines. Of these, 80.5% participated in the study, though only 21.2% provided complete data for calculating aRUR and oRUR, and 48.5% of participating hospitals’ aRUR could be analyzed.

aRUR and oRUR in colon cancer

The study calculated an average aRUR of 5.3% for colon cancer. While this suggests oRUR fulfillment, extrapolated data (Table 4) indicated significant gaps. Earlier studies comparing aRUR and oRUR showed variations; for instance, Delaney et al. reported oRUR of 14% (4–23%) for colon cancer, while by 2013, it had decreased to 4% (4–6.2%) in Australia [11, 14, 15].

Table 4

Sensitivity analysis

| Parameters | oRUR (%) | aRUR (%) | Percentage of unmet need |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colon cancer | 3.3 (3–3.7) | 0.5–5.3 | –76.7–86.6 |

| Rectal cancer | 41 (28–66) | 4.4–22.5 | 19.5–93.3 |

| Colorectal cancer | 26.21 (18.19–41.56) | 2.4–15.3 | 21.4–96.6 |

Factors influencing higher aRUR include multidisciplinary discussions, rectosigmoid cancer inclusion (10% of colorectal cases), and differing colon cancer indications in Indonesia vs. the 2012 CCORE publication. Lievens et al. advised a 1.7–17% RUR from multidisciplinary input [16]. Radiotherapy’s limited role in colon cancer contrasts with its frequent use for rectal cancer in neoadjuvant or non-surgical therapy. Diagnostic challenges due to advanced disease stages complicate tumor origin determination, affecting treatment accuracy [17, 18].

In a follow-up analysis, 105 patients were reported with T4 tumors, including 29 non-metastatic cases. Among these, four patients underwent radiotherapy, representing 6.3% of all irradiated colon cases and 0.3% of all colon cases. This may reflect variations in treatment guidelines. According to Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital’s 2016 clinical guideline and the 2017 Indonesian National Clinical Guideline for Colorectal Cancer, radiotherapy is recommended only for rectal cancer [4, 19]. Conversely, the 2012 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for colon cancer suggest adjuvant radiotherapy for non-metastatic T4 cases, combined with concurrent chemotherapy using 5-FU to improve tumor resectability. Radiotherapy is also considered for lung or liver metastases [20]. In this study, the aRUR increased due to neoadjuvant radiation for non-metastatic T4 cases and the high prevalence of locally advanced cancers.

Rectal cancer aRUR and oRUR/aRUR and oRUR in rectal cancer

Our findings showed significant variability in oRUR and aRUR for rectal cancer across hospitals, with an average oRUR of approximately 41%. Radiotherapy utilization remains suboptimal (Table 3), with more significant disparities in centers reporting fewer than 50 cases, potentially introducing bias. Demographic factors and varying risk patterns may influence these differences.

In a 2004 study by Delaney et al., the average oRUR for rectal cancer was 61%, while aRURs were 34% in the U.S., 38% in Australia, and 33% in Great Britain [14]. Similarly, the ESTRO-HERO project reported oRURs for rectal cancer in Europe of 55.9–72% [21]. Yap et al. adjusted colorectal cancer models for low-income countries, excluding early-stage rectal cancer (T1N0M0), and found that oRUR increased 22–24%. Using this model, our study estimated a colorectal oRUR of 26.2% (15.2–47.6%), aligning with Yap et al. findings for low-income countries [10].

Indonesian guidelines align with international standards, recommending radiotherapy for stage 2–4 rectal cancer [4, 19]. According to NCCN guidelines, radiotherapy is appropriate for rectal cancer stages beyond T1N0M0 and T2N0M0, excluding cases without high-risk features like positive margins or lymphovascular invasion [22–24].

Based on centers with complete data submissions, the aRUR was highest in T3-4/N1-2 M0 and TxNxM1 cases, accounting for 49.2% and 36.1% of cases in each group, respectively. For T1 or 2, N0M0 cases, only 10 of 1,158 cases had an aRUR of 100% and 37.5% (2 and 8 cases, respectively). Optimizing radiotherapy for the two groups with the highest utilization could help achieve the expected optimal aRUR for rectal cancer. Previous studies have recommended increasing radiotherapy usage for locally advanced and metastatic rectal cancer cases. As most rectal cancer cases in this study were stage III and IV, the indications for radiotherapy increased, suggesting a higher aRUR should be achieved.

Several factors contribute to the suboptimal RUR for colon and rectal cancer. Patient-related issues, clinician decisions, cancer characteristics, and bureaucratic challenges were identified as the primary barriers. A National Cancer Control Plan is essential to address these gaps. Gondhowiardjo et al. highlighted that patient anxiety regarding medical treatment and a preference for alternative therapies delayed management, worsening utilization rates [25]. However, radiotherapy usage in Indonesia is expected to improve as the availability of equipment, treatment centers, and regionalization has significantly increased over the past decade. Awareness campaigns are also raising public knowledge about the benefits of radiation the- rapy [26].

Conclusions

Despite Indonesia’s advancements in radiotherapy, disparities in colorectal cancer RUR persist. While the actual RUR (aRUR) for colon cancer approaches the optimal RUR (oRUR) based on available data, a significant gap remains for rectal cancer. Extrapolations using the 2019 IROS survey and GLOBOCAN data reveal even broader disparities in both colon and rectal cancer RUR across larger populations.

To bridge these gaps, targeted interventions are necessary. First, capacity-building initiatives should focus on expanding the number of trained radiotherapy-related personnel, particularly in underserved regions, through specialized training programs and incentives for practitioners to work in remote areas. Second, infrastructure development should prioritize the establishment of new radiotherapy centers equipped with modern technology to improve access and treatment efficiency. Third, policy reforms should streamline bureaucratic processes, ensuring financial and administrative barriers do not delay or limit patient access to necessary radiotherapy. Additionally, a comprehensive national cancer control plan should be implemented to standardize treatment guidelines, optimize resource allocation, and integrate radiotherapy into multidisciplinary colorectal cancer management. Future studies should also refine radiotherapy indications for colon cancer, particularly in cases such as T4 or rectosigmoid tumors, and assess center-specific factors influencing RUR in each center across Indonesia. Lastly, the inclusion of oligometastatic cases in treatment decision frameworks should be considered in the next revision of clinical guidelines based on the best available evidence.