Summary

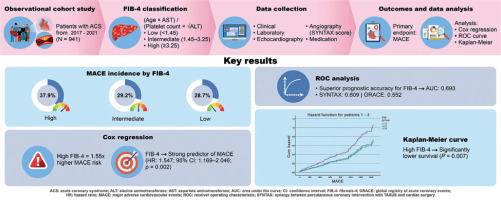

This study investigated the prognostic value of the Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index, a non-invasive liver fibrosis marker, in predicting major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). A total of 941 patients hospitalized with ACS were categorized into low, intermediate, and high FIB-4 groups and followed for a median of 67.5 months. The incidence of MACE was significantly higher in the high FIB-4 group (37.9%) compared to the low and intermediate groups (28.7% and 29.2%, respectively). Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified FIB-4 as an independent predictor of MACE (HR = 1.547), and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis showed that FIB-4 had better predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.693) than traditional clinical scores such as SYNTAX (AUC = 0.609) and GRACE (AUC = 0.552). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis further confirmed that patients with high FIB-4 values had significantly lower survival. The study concludes that FIB-4, by reflecting systemic metabolic and inflammatory burden, can serve as a simple, cost-effective, and superior tool for cardiovascular risk stratification in ACS patients, supporting its potential integration into routine clinical assessment.

Introduction

Due to similarities in cardiometabolic risk factors, the etiologies of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) often follow parallel trajectories. Parameters of metabolic syndrome such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia, and abdominal obesity are prevalent in a substantial portion of patients with ACS [1].

ACS is characterized by thrombotic processes that can lead to dramatic and life-threatening complications, and remains one of the most common causes of mortality worldwide. Concurrently, NAFLD, sharing common risk factors, has been identified as associated with increased mortality and morbidity in ACS [2]. Risk assessment and prognosis prediction in ACS are clinically significant, influencing both the duration of hospital stay and the intervals for follow-up. Hence, there is a growing interest in identifying novel biomarkers that can enhance the prognostic accuracy beyond conventional clinical and biochemical parameters [3].

The Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index is a non-invasive scoring system initially developed to evaluate liver fibrosis in NAFLD [4]. This index distinguishes patients with significant fibrosis from those without, and is particularly useful in the clinical setting because it does not require advanced imaging or biopsy. The simplicity and cost-effectiveness of FIB-4 make it widely used in routine clinical practice.

Recently, the relevance of FIB-4 has expanded into other areas of medicine, including cardiology, suggesting its potential role in systemic inflammation and cardiovascular diseases [5]. Systemic inflammation plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis and progression of ACS. Elevated levels of hepatic enzymes, which are components of FIB-4, are associated with poor cardiovascular outcomes, positing FIB-4 as a predictor of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in patients with ACS [6].

Aim

Therefore, we aimed to investigate the prognostic value of FIB-4 in predicting MACE in patients presenting with ACS. Furthermore, we compared its predictive ability with two established cardiovascular risk models, the SYNTAX and GRACE scores, to assess whether this metabolic fibrosis index could serve as a complementary or superior tool in the prognosis of ACS. This approach may offer a simple, cost-effective tool to enhance current risk stratification methods and improve clinical decision-making in the management of patients with ACS.

Material and methods

Study population

This observational cohort study included 941 consecutive patients treated for ACS with symptoms of angina or equivalent, admitted to the cardiology clinic between January 2017 and December 2021. Eligible participants over 18 years of age diagnosed with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (non-STEMI), and unstable angina pectoris, who underwent coronary angiography followed by medical monitoring and percutaneous and/or surgical revascularization, were included. Patients with chronic liver disease, carriers or patients of hepatitis B or C, those infected with human immunodeficiency virus, and those diagnosed with any malignancy were excluded from the study. Additionally, individuals consuming more than 20 g of alcohol per day and those with a history of using chemotherapeutic drugs that have toxic effects on the liver, such as steroids, estrogens, amiodarone, or tamoxifen, were excluded. Patients with incomplete data – defined as missing values in any of the core clinical, laboratory, or follow-up variables – were also excluded from the analysis.

The study protocol was granted ethical approval by the local ethics committee (approval number 2025/296 issued on 07.05.2025). In compliance with international standards, the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. This consent process ensured that all individuals were fully informed of the study purpose, the procedures involved, potential risks, and their rights as study participants, including the right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence.

Data collection and definitions

All patients were followed for the occurrence of MACE through a combination of hospital records, scheduled outpatient visits, and telephone interviews. Follow-up was conducted at 6-month intervals for up to 5 years. The median duration of follow-up was 67.5 months (interquartile range (IQR): 25–96). Events were confirmed by clinical documentation and adjudicated by two independent cardiologists.

The diagnosis of ACS, including STEMI, non-STEMI, and unstable angina, was based on the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction [7]. This included clinical symptoms of ischemia, dynamic electrocardiographic changes, and elevated cardiac biomarkers (primarily troponin), confirmed by coronary angiography.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (including age and sex) were systematically recorded for all participants. The presence of comorbid conditions, specifically DM, hypertension (HT), and dyslipidemia, was documented through a review of each patient’s medical history and verification of ongoing medication regimens. HT was defined as systolic blood pressure > 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure > 90 mm Hg or patients already on hypertension treatment. DM was defined as fasting glucose readings > 126 mg/dl in two measurements, glycated hemoglobin > 6.5%, or patients previously diagnosed with DM and on treatment. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was measured using the Cockcroft-Gault equation [8].

As part of the initial evaluation, laboratory data were obtained within the first 24 h of hospital admission, after an overnight fasting period of 8–12 h. Blood tests included a complete blood count (with platelet count), liver function tests – aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) – and a fasting lipid profile (total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides). Using these laboratory values, the FIB-4 index was calculated for each patient according to the following formula: FIB-4 = (age × AST)/(platelet count × √ALT) [9]. The resulting FIB-4 values were then stratified into three categories for risk assessment: low, FIB-4 < 1.45; intermediate, 1.45–3.25; and high, ≥ 3.25 [10].

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed for all patients during the index hospitalization, and conventional echocardiographic parameters were recorded. This included measurement of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) along with assessment of cardiac chamber sizes, wall motion abnormalities, and valvular function. LVEF was quantified using the modified biplane Simpson’s method in apical two- and four-chamber views, in accordance with standard echocardiography guidelines.

All patients underwent coronary angiography for evaluation of coronary anatomy and extent of disease. The complexity of coronary artery disease was quantified by calculating the Synergy Between PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) score for each patient. The SYNTAX score, an established angiographic tool that grades the complexity and severity of coronary artery disease, was determined by experienced interventional cardiologists using the standard SYNTAX scoring algorithm [11]. For each coronary lesion identified, the scoring algorithm accounts for features such as lesion location, presence of total occlusions, bifurcation lesions, calcification, and vessel tortuosity, summing these to yield an overall SYNTAX score. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events Score (GRACE) risk score was calculated using the standard algorithm based on age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, serum creatinine, Killip class, cardiac arrest at admission, ST-segment deviation, and elevated cardiac biomarkers. The score was computed electronically using the GRACE calculator, and the values were recorded at the time of admission [12].

Medication data were also collected, particularly regarding acute antiplatelet therapy. In accordance with current ACS treatment protocols, all patients received dual antiplatelet therapy. Each patient was administered a loading dose of a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor on presentation – either ticagrelor (180 mg) or clopidogrel (300–600 mg) – based on clinical indications and the treating physician’s discretion. This was followed by maintenance therapy with ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily or clopidogrel 75 mg once daily, respectively. Additionally, aspirin was administered to all patients (300 mg loading dose, followed by 81–100 mg daily) as part of the dual antiplatelet regimen, unless contraindicated. This standardized approach to antiplatelet therapy was maintained throughout the hospitalization for all patients with ACS in the study.

Following the commencement of dual antiplatelet therapy, a routine catheterization process involving selective contrast injections into both the right and left coronary artery systems was carried out prior to the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the identified culprit lesion for all patients. The choice of pre-dilatation of the culprit lesion and the PCI technique employed was at the discretion of the operating physician.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 23.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and main outcomes of the study. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median with IQR, depending on distribution, as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. For inferential statistics, the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables between groups, while Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test was applied for continuous variables, based on the normality of the data. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated to assess the accuracy of the FIB-4 index, with values closer to 1.0 indicating better discriminative ability. Confidence intervals for the AUC were computed to provide an estimate of the precision of the ROC analysis. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the time to occurrence of MACE, and differences between groups based on FIB-4 categories (low, intermediate, high) were assessed using the log-rank test. For all analyses, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In this retrospective observational cohort study 1,098 patients were evaluated, 941 (85.7%) patients met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study, while 157 (14.3%) patients were excluded due to incomplete data or as per the exclusion criteria. The median clinical follow-up period was 67.5 months (IQR: 25–96 months). The mean age of the included patients was 60.2 ±11.7 years, with 71% (n = 668) being male. The in-hospital mortality rate for patients hospitalized with ACS was 5.95% (n = 56), and the occurrence rate of MACE during the follow-up period was 30.8% (n = 290) (Figure 1). Demographic data, patient characteristics, vital signs at presentation, laboratory values, and calculated scores for GRACE, SYNTAX, and FIB-4 index are presented in Table I.

Table I

Baseline characteristics, clinical parameters, and outcomes according to major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome

| Parameter | Overall | MACE (290) | Survival (651) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 60.2 ±11.7 | 66.8 ±11.5 | 57.3 ±10.6 | < 0.001 |

| Male gender, % (n) | 71 (668) | 65.9 (191) | 73.3 (477) | 0.021 |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 59.1 (556) | 74.8 (217) | 52.1 (339) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % (n) | 36.3 (342) | 45.9 (133) | 32.1 (209) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia, % (n) | 52 (489) | 49 (142) | 53.3 (347) | 0.21 |

| Previous CAD, % (n) | 26.8 (252) | 31 (90) | 24.9 (162) | 0.06 |

| Current smokers, % (n) | 53.5 (503) | 46.6 (135) | 56.5 (368) | 0.005 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 27.8 ±4.5 | 28.6 ±4.8 | 27.4 ±4.3 | 0.012 |

| Statin usage, % (n) | 39.8 (375) | 43.4 (126) | 38.2 (249) | 0.08 |

| Heart rate [bpm] | 80.8 ±19.6 | 76.6 ±13.7 | 83.1 ±20.1 | < 0.001 |

| Systolic BP [mm Hg] | 138.3 ±25.4 | 136.4 ±21.6 | 139.4 ±26.2 | 0.25 |

| Diastolic BP [mm Hg] | 83.0 ±13.1 | 81.8 ±11.4 | 83.5 ±13.5 | 0.15 |

| Fasting glucose [mg/dl] | 128.1 ±133.9 | 138.6 ±64.6 | 123.4 ±53.1 | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.8 ±1.7 | 7.24 ±1.8 | 6.6 ±1.6 | < 0.001 |

| ALT [u/l] | 25.6 ±31.5 | 26.3 ±50.6 | 25.3 ±17.4 | 0.66 |

| AST [u/l] | 40.1 ±10.4 | 45.4 ±93.2 | 37.7 ±34.8 | 0.07 |

| Total C [mg/dl] | 188.3 ±47.4 | 183.5 ±45.7 | 190.4 ±48.0 | 0.040 |

| LDL-C [mg/dl] | 125.5 ±41.0 | 120.3 ±41.5 | 127.8 ±40.6 | 0.009 |

| HDL-C [mg/dl] | 38.4 ±11.1 | 39.0 ±12.2 | 38.2 ±10.6 | 0.30 |

| Triglyceride [mg/dl] | 184.4 ±133.9 | 168.1 ±105.8 | 191.7 ±144.2 | 0.013 |

| eGFR [ml/min/1.73 m2] | 93.5 ±32.9 | 75.9 ±29.4 | 101.3 ±31.4 | < 0.001 |

| Hgb [g/l] | 13.38 ±1.88 | 12.85 ±2.04 | 13.62 ±1.75 | < 0.001 |

| Platelets, [× 109/l] | 247.54 ±72.85 | 256.06 ±84.94 | 243.75 ±66.50 | 0.017 |

| WBC [× 109/l] | 9.61 ±2.91 | 9.61 ±2.80 | 9.60 ±2.96 | 0.63 |

| Leu [× 109/l] | 2.36 ±0.98 | 2.17 ±0.96 | 2.45 ±0.98 | < 0.001 |

| Mon [× 109/l] | 0.67 ±0.28 | 0.68 ±0.31 | 0.67 ±0.26 | 0.63 |

| Neut [× 109/l] | 6.26 ±2.67 | 6.40 ±2.57 | 6.20 ±2.70 | 0.27 |

| LVEF, % | 52.73 ±9.22 | 49.00 ±11.43 | 54.40 ±7.47 | < 0.001 |

| GRACE score | 136.95 ±35.44 | 149.21 ±35.28 | 124.70 ±34.96 | < 0.001 |

| SYNTAX | 13.57 ±11.02 | 16.63 ±11.80 | 12.21 ±10.38 | < 0.001 |

| Hospital stay [days] | 6.40 [3–7] | 7.76 ±5.89 | 5.80 ±4.44 | < 0.001 |

| FIB-4 index | 2.06 ±1.43 | 2.49 ±3.74 | 1.87 ±1.44 | < 0.001 |

[i] MACE – major cardiovascular adverse event, CAD – coronary artery disease, BMI – body mass index, bpm – beats per minutes, BP – blood pressure, ALT – alanine aminotransferase, AST – aspartate aminotransferase, Total C – total cholesterol, LDL-C – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C – high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate, Hgb – hemoglobin, WBC – white blood cell, Leu – leukocytes, Mon – monocytes, Neut – neutrophils, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, FIB-4 – Fibrosis-4 index.

Patients in the MACE group were statistically significantly older compared to the survival group (66.8 ±11.5 vs. 57.3 ±10.6; p < 0.001). Hypertension, DM, and previous coronary artery disease were more commonly observed in the MACE group, whereas higher rates of hyperlipidemia and active smoking were seen in the survival group (Table I). Statistically significantly higher levels of cholesterol parameters (total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides) were observed in the survival group without MACE (p-values = 0.040, 0.009, and 0.013, respectively).

After stratification by FIB-4, the baseline characteristics showed significant differences across the groups in terms of age, with the high FIB-4 group being the oldest (age 64.8 ±12.3 years) and showing a higher prevalence of MACE at 37.9% compared to 28.7% in low and 29.2% in intermediate FIB-4 group (p = 0.046). Comorbidity profiles also varied significantly with FIB-4 risk categorization, particularly for hypertension and hyperlipidemia, which showed greater prevalence in higher FIB-4 categories (Table II).

Table II

Clinical outcomes and patient characteristics by FIB-4 index categories in acute coronary syndrome patients

[i] The resulting FIB-4 values were then stratified into three categories for risk assessment: low (FIB-4 < 1.45), intermediate (1.45–3.25), and high (≥ 3.25). FIB-4 – Fibrosis-4 index, MACE – major adverse cardiovascular events, CAD – coronary artery disease, SYNTAX score – Synergy Between PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery score, GRACE Score – Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events Score, Total C – total cholesterol, LDL-C – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Tg – Triglycerides, HbA1c – hemoglobin A1c, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate, MI – myocardial infarction, SVO – stroke or vascular occlusion.

Cox regression analysis underscored the FIB-4 index as a strong predictor of MACE, with an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 1.547 (95% CI: 1.169–2.046, p = 0.002). This model also confirmed the independent predictive relevance of age and the SYNTAX score, with HRs of 1.059 (95% CI: 1.044–1.074, p < 0.001) and 1.016 (95% CI: 1.005–1.026, p = 0.003), respectively (Table III).

Table III

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of factors influencing major adverse cardiovascular events in acute coronary syndrome patients

| Variables | Exp B (OR) | CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.059 | 1.044–1.074 | < 0.001 |

| Gender | 1.217 | 0.938–1.579 | 0.140 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.262 | 0.996–1.598 | 0.054 |

| SYNTAX | 1.016 | 1.005–1.026 | 0.003 |

| GRACE | 1.013 | 0.990–1.017 | 0.097 |

| FIB-4 | 1.547 | 1.169–2.046 | 0.002 |

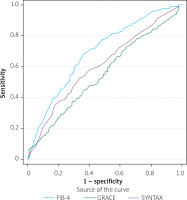

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis further substantiated the diagnostic utility of the FIB-4 index, achieving an AUC of 0.693 (95% CI: 0.658–0.729, p < 0.001), outperforming both SYNTAX (AUC = 0.609, p = 0.008) and GRACE scores (AUC = 0.552, p = 0.10) in predicting clinical outcomes (Table IV, Figure 2).

Table IV

Receiver operating characteristic analysis for assessing the predictive power of FIB-4, SYNTAX, and GRACE scores in patients with acute coronary syndrome

| Variable | Area under curve | CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIB-4 | 0.693 | 0.658–0.729 | < 0.001 |

| SYNTAX | 0.609 | 0.570–0.649 | 0.008 |

| GRACE | 0.552 | 0.511–0.592 | 0.102 |

Figure 2

ROC curve analysis of FIB-4, SYNTAX, and GRACE scores to assess clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndrome patients. Comparison of ROC curves evaluating the discriminatory ability of the FIB-4 index, SYNTAX score, and GRACE score in predicting major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). The FIB-4 index showed superior predictive performance (AUC = 0.693), compared to SYNTAX (AUC = 0.609) and GRACE (AUC = 0.552)

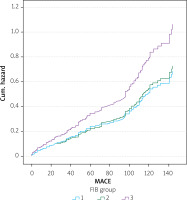

Kaplan-Meier plots illustrated that patients in the high FIB-4 category had significantly lower survival probabilities than those in lower risk categories (p = 0.007), affirming the prognostic severity indicated by higher FIB-4 values (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for acute coronary syndrome patients stratified by FIB-4 categories. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) χ2 = 10.065, p-value = 0.007. Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating the cumulative MACE-free survival over time, stratified by FIB-4 index categories: low (< 1.45), intermediate (1.45–3.25), and high (≥ 3.25). Patients in the high FIB-4 group demonstrated significantly lower event-free survival compared to those in the other categories (log-rank p = 0.007)

Discussion

An elevated FIB-4 index was directly associated with MACE following ACS and demonstrated greater sensitivity in predicting MACE compared to clinical scores such as the GRACE and SYNTAX scores. Our findings highlight that elevated FIB-4 scores correlate with increased MACE, aligning with previous studies regarding the predictive value of systemic inflammation and hepatic function markers in cardiovascular disease outcomes. The prognostic relevance of the FIB-4 index in the context of ACS marks a significant advancement in cardiovascular risk stratification, extending its utility beyond its traditional domain within hepatological disorders.

NAFLD is more than simply a hepatic condition, having significant implications for cardiovascular health. The pathophysiological links between NAFLD and coronary artery disease (CAD) are becoming clearer, underscoring a shared foundation in metabolic dysfunction. NAFLD and CAD share common metabolic risk factors, including insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension – each a critical component of the metabolic syndrome that contributes to pathogenic processes in both the liver and the cardiovascular system [13]. Indeed, the presence of NAFLD has been associated with an increased risk of developing CAD, suggesting that the liver disease may not only be a marker of systemic metabolic dysregulation but also an active contributor to the development of cardiovascular disease [14, 15]. This overlap suggests that incorporating NAFLD assessment into cardiovascular risk evaluation could provide a more comprehensive understanding of a patient’s health status, potentially leading to earlier intervention and better management of both hepatic and cardiac risks [16]. Thus, evaluating NAFLD could enhance cardiovascular risk stratification and improve preventive strategies in general and high-risk populations.

Given the intertwined relationship between NAFLD and systemic metabolic disorders, the FIB-4 index, initially developed to assess liver fibrosis in NAFLD patients, emerges as a valuable tool to identify individuals at elevated risk of cardiovascular diseases. This connection supports the utility of FIB-4 not only in hepatic evaluations but also as a predictor of cardiovascular complications in patients with NAFLD [5, 17].

Although current risk scores make significant outcome predictions based on angiographic and clinical data, the metabolic assessment of the patient and the inclusion of these parameters in scoring models are crucial [18]. A meta-analysis, which included over 34,000 patients across 16 studies with a median follow-up duration of 6.9 years, showed that NAFLD significantly increases the frequency of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events (OR = 2.58, 95% CI: 1.78–3.5) [19]. In another comprehensive meta-analysis, encompassing 36 longitudinal studies of 5,802,226 middle-aged adults (mean age: 53 ±7 years) with 99,668 reported instances of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular disease (CVD) events over a median follow-up period of 6.5 years, a robust association was found between NAFLD and a heightened long-term risk of CVD events; the pooled hazard ratio (HR) was calculated at 1.45 (95% CI: 1.31–1.61) [20]. The risk of CVD was even greater among individuals with more severe liver disease, particularly those at advanced stages of fibrosis. In a study analyzing the correlation between the SYNTAX score and NAFLD in patients with ACS, patients with a SYNTAX score of 15 or higher exhibited significantly higher prevalence of NAFLD. In patients with ACS who also had NAFLD, the coronary anatomy was observed to be more challenging and complex. This finding suggests that NAFLD may contribute to the severity of CAD, necessitating more comprehensive assessments in patients with high SYNTAX scores [21].

While liver biopsy is traditionally viewed as the definitive method to diagnose and assess the severity of NAFLD, modern guidelines advocate for the use of clinical scoring systems in all NAFLD cases [22]. Among these, the FIB-4 index stands out due to its straightforwardness, wide availability, and proven dependability. It not only serves as a method to gauge liver-related complications in NAFLD patients but has also been linked to a heightened cardiovascular risk. Furthermore, evidence from a recent comprehensive meta-analysis, which included 12 studies and 25,252 CVD patients, indicates a strong correlation between elevated initial FIB-4 levels and increased incidence of cardiovascular events (HR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.53–2.00), cardiovascular mortality (HR = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.19–3.61), and overall mortality (HR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.24–2.66) [23].

In a study investigating the relationship between the uric acid to HDL-cholesterol ratio and the SYNTAX score, metabolic parameters associated with increased cardiovascular risk were found to be effective in predicting the severity of coronary artery disease [24].

Biccirè et al. demonstrated that in-hospital mortality after ACS is associated with liver fibrosis [25], observing that a high FIB-4 index is associated with increased in-hospital complications and poorer outcomes. Additionally, the FIB-4 index correlates with an increased incidence of MACE following ACS, in line with our results. Particularly, in patients with an FIB-4 index above 3.25, there was a 3.1-fold higher rate of in-hospital adverse events compared to those with lower scores [25]. This further underscores the importance of considering liver fibrosis in the clinical management of patients with ACS.

In another study involving 612 patients who underwent coronary computed tomographic angiography, a 5-year follow-up assessed the implications of liver fibrosis. It was found that an FIB-4 score of 2.67 or higher serves as an independent predictor of MACE in hypertensive patients. This reinforces the significance of the FIB-4 score in identifying cardiovascular risk among patients with existing cardiovascular conditions [26].

In an observational study from Sri Lanka involving 120 patients with ACS, NAFLD significantly increased the risk of mortality, as estimated by the GRACE score. Individuals with NAFLD exhibited a substantially higher risk of mortality during their hospital stay (OR = 31.3, 95% CI: 2.2–439.8, p = 0.011) and at 6 months post-discharge (OR = 15.59, 95% CI: 1.6–130.6, p = 0.011) [1]. Patients with an FIB-4 index over 3.25 exhibited a clearly elevated incidence of MACE, as shown in the hazard curve, compared to other groups. The same observation was made in our study, and the notable rise highlights the risk associated with higher FIB-4 levels in predicting cardiovascular outcomes.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the FIB-4 index is not only predictive of long-term outcomes but also associated with increased in-hospital and periprocedural mortality in patients with ACS, suggesting that liver fibrosis may reflect systemic vulnerability affecting early adverse events during hospitalization and intervention [27]. While our study focused on long-term events, a separate evaluation of FIB-4 in the context of in-hospital outcomes remains an important area for future research.

Another accessible marker is the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, derived from fasting glucose and triglyceride levels. It has shown predictive value for cardiovascular events and short-term mortality in ACS and post-PCI patients [28]. Comparative studies of FIB-4 and TyG may help refine risk models in acute settings.

In addition, established clinical variables such as Killip class, baseline renal function, and LVEF remain critical for perioperative risk stratification. Composite scores such as GRACE and TIMI may be enhanced by incorporating hepatic or metabolic indices such as FIB-4 or TyG [29]. Such integration of non-traditional risk markers into established scoring systems has also been supported in recent literature, which highlights the evolving nature of prognostic modeling in ACS [30]. Furthermore, recent national registry data emphasize the importance of refined risk stratification for perioperative mortality and sudden cardiac arrest, underscoring the relevance of incorporating clinical and metabolic predictors [31]. Taken together, the accumulating evidence underscores the added value of metabolic and hepatic markers in contemporary risk stratification; nevertheless, several study constraints should be acknowledged.

Our study had some limitations. While the FIB-4 index is a significant marker for liver fibrosis in NAFLD, liver biopsy remains the gold standard. One major limitation of our study is the lack of biopsy confirmation to support the scoring. Additionally, the retrospective nature of our study limits the availability of data regarding past medical conditions and medication usage, which could influence the outcomes. The prevalence of risk factors such as DM and hyperlipidemia in the MACE group may dilute the apparent impact of the FIB-4 index alone. Further subgroup analyses including gender and DM may alter the results. Another limitation is the lack of separate reporting for different MACE subgroups – such as myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular events, death, and hospitalization – within the follow-up period, which restricts a more detailed outcome analysis.

Conclusions

The FIB-4 index, recognized as a scoring system accepted in NAFLD for its encapsulation of biomarkers indicative of liver health, provides significant metabolic data. This index has been used to assess outcomes of ACS, one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, highlighting its relevance to cardiovascular health. The affordability and simplicity of calculating the FIB-4 index allow it to serve not only as a predictor of MACE but also to demonstrate greater sensitivity and specificity in predicting MACE outcomes when compared to other scoring systems such as the GRACE and SYNTAX scores. This article underscores the utility of FIB-4 as a multifaceted tool in the clinical evaluation of patients with ACS, suggesting that broader metabolic and hepatic health assessments could be integral components of cardiovascular risk management strategies. The integration of such tools into clinical practice requires further validation through prospective studies, which should also consider detailed subgroup analyses to enhance the understanding of the index’s predictive power across different patient demographics.