Summary

Balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) is traditionally performed in hybrid theaters or hospitals with cardiac surgery backup, but limited availability has led to its use in standalone catheterization laboratories (ASC). This study compared the safety and efficiency of BAV in ASC versus cardiac surgery-backed units (CSBU) in a multicenter registry of 514 patients. Despite a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease and anemia in the ASC group, outcomes – including in-hospital mortality, tamponade, bleeding, and pacemaker implantation – were comparable. Both groups showed significant reductions in transvalvular gradient. These findings confirm that BAV in ASC is a safe and effective alternative to procedures conducted in CSBU.

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valvular disease in the elderly population and is typically treated with specific interventions in high-risk groups [1]. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV), first introduced by Cribier et al., involves dilating the aortic valve cusps and annulus, causing microfractures in valve calcifications and partially separating the commissures. Initially, BAV was an alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) for patients with severe calcified AS who were unsuitable for surgery due to other health issues [2–4].

However, BAV’s popularity declined due to high rates of restenosis, symptom recurrence within 6 months, and mortality rates in untreated patients [5, 6]. A significant complication of BAV is uncontrollable aortic regurgitation (AR), often necessitating urgent SAVR [7].

The introduction of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) renewed interest in BAV, using it as a diagnostic tool for patients with other potential causes of symptoms (e.g., advanced lung disease) or as a bridge to valve replacement in acute, decompensated AS cases with significant contraindications to TAVR [2, 5].

The frequency of aortic valvuloplasty has significantly increased as a critical part of the transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) procedure and as a bridging strategy. In the TAVI technique, BAV is essential for assessing the annular size, evaluating the displacement of aortic valve leaflets near the left main coronary artery, and facilitating the placement of the percutaneous valve [3, 4]. Additionally, BAV can be considered palliative in cases where severe comorbidities contraindicate surgery, and TAVI is not feasible [3].

Aim

In our study, we compared the safety and efficiency of BAV, typically performed in hybrid theaters or hospitals with cardiac surgery wards, when conducted in standalone catheterization laboratories (ASC) versus cardiac surgery-backed units (CSBU).

Material and methods

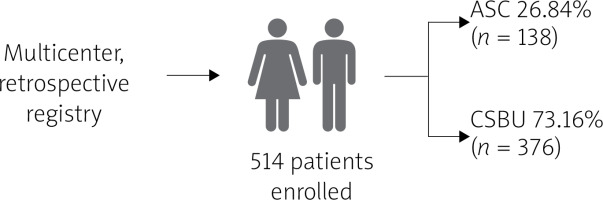

This was a multicenter, retrospective registry of symptomatic patients admitted to cardiology departments with severe AS who underwent BAV. The analyzed group numbered 528 patients; 71.2% (n = 376) of them were performed in the CSBU, and 28.8% (n = 152) in ASC (Figure 1).

Endpoints

The endpoints consisted of stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), myocardial infarction (MI), sudden cardiac death (SCD), all-cause mortality, incidence of tamponades, and significant bleeding requiring transfusions. Post-procedure reduction in transvalvular gradient in both ASC and CSBU settings was also evaluated.

Clinical endpoints were identified retrospectively based on available documentation, including procedural records, echocardiographic assessments, and hospital discharge summaries. Stroke/TIA and myocardial infarction were defined according to current ESC guidelines. Significant bleeding was defined as any event requiring red blood cell transfusion or associated with hemodynamic instability. Tamponade was defined as pericardial effusion requiring drainage or causing hemodynamic compromise.

BAV procedure

BAV was performed using a standard technique that follows this sequence. Initially, patients underwent thorough evaluation, including echocardiography and possibly coronary angiography. After obtaining informed consent and administering pre-procedure medications, the procedure began with local anesthesia and sedation. A vascular sheath was inserted into the femoral artery to facilitate catheter introduction. A guidewire was advanced into the aortic valve, followed by a balloon-tipped catheter. Using fluoroscopic guidance, the balloon catheter was precisely positioned across the stenotic valve orifice and inflated to dilate the valve leaflets, thereby reducing the stenosis. This inflation was meticulously controlled and repeated to achieve optimal valve opening. Following balloon inflation, the catheter was withdrawn, and the hemodynamic improvement was assessed through pressure gradient measurements. The vascular sheath was removed, and hemostasis was achieved using manual compression or a closure device. Patients were closely monitored for potential complications, with regular vital signs and access site checks. A follow-up echocardiogram was performed to evaluate the procedural outcome. Patients typically remained hospitalized for observation and were discharged with detailed post-procedure instructions.

Ethics committee

Due to this study’s retrospective and observational character, the ethics committee’s approval and the patient’s consent were not required.

Statistical analysis

Numerical data were expressed as mean and standard deviation and, depending on the distribution, the Mann-Whitney test and Student’s t-test were used. Categorical data were presented as percentages and as absolute numbers and were compared with the χ2 test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The analyzed groups did not differ statistically significantly in terms of demographic data. Men constituted 39.47% (n = 60) in the ASC group and 40.43% (n = 152) in the CSBU group. The median age was similar in both groups, 81.5 in the ASC group and 82 in the CSBU group. We observed statistically significant differences in clinical data in the following characteristics between ASC and CSBU groups: hypertension 84.21% vs. 63.83% (p < 0.01); percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the last 12 months 34.21% vs. 18.09% (< 0.01); hypercholesterolemia 52.63% vs. 13.56% (p < 0.01); coronary artery disease (CAD) 59.21% vs. 44.95% (p = 0.03); anemia 44.73% vs. 11.97% (p < 0.01) (Table I).

Table I

Clinical characteristics

Upon admission, patients underwent echocardiography. Statistically significant differences were observed between the ASC and CSBU groups in the following parameters: median left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 50% vs. 55% (p = 0.02); peak aortic jet velocity (Vmax) was 4.3 m/s versus 4.6 m/s (p < 0.01); and maximum pressure gradient (PG max) was 73 mm Hg versus 88 mm Hg (p < 0.01) (Table II).

Table II

Echocardiography before the procedure

Balloon dilatation with 18–24 mm diameter balloon catheters reduced the transvalvular gradient in both groups significantly (ASC: 49.6 ±8.2 mm Hg to 34.4 ±5.2 mm Hg p = 0.01 and CSBU: 50.2 ±7.3 mm Hg to 36.5 ±4.3 mm Hg). Moreover, there were no significant differences between groups in the transvalvular gradient after the procedure.

The groups did not differ regarding complications after the procedure (Table III).

Table III

Complications

Discussion

BAV is recognized as an effective palliative procedure for patients with severe aortic stenosis who are not immediately eligible for more invasive treatments due to various risk factors. Although long-term benefits are limited, this procedure significantly improves hemodynamics and symptoms [8–10]. Benefits typically last 6–12 months, making BAV an important bridging option. It is also beneficial in complex cases where time is needed due to numerous comorbidities or for patients preparing for non-cardiac surgery. Compared to TAVI and SAVR, BAV is less costly, making it a practical option in healthcare systems with limited resources [11]. The procedural success rate of BAV is estimated at 94.6%, with a 30% reduction in the mean transvalvular gradient, confirming its safety and cost-effectiveness in high-risk patients [12].

The ESC guidelines recommend BAV as a class IIb intervention for managing severe AS, particularly as a bridge to SAVR or TAVI in hemodynamically unstable patients and as a palliative measure for those ineligibles for SAVR or TAVI due to severe comorbidities. BAV carries risks such as vascular complications, MI, and stroke and is contraindicated in patients with specific conditions. Despite these risks, BAV provides immediate symptom relief, although restenosis remains a concern. Decision-making for BAV should involve a multidisciplinary heart team to ensure comprehensive patient care [5, 13, 14].

Although common among patients undergoing BA, comorbidities such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, CAD, and a history of PCI do not appear to significantly influence procedural outcomes or short-term prognosis. These factors, while important in the context of general cardiovascular risk, have not consistently been shown to affect the safety or efficacy of BAV. This may be due to the fact that BAV is often used as a bridge or palliative procedure in patients with severe aortic stenosis and multiple comorbidities, where other factors – such as hemodynamic instability, frailty, conduction disturbances, or anemia – play a more dominant role in determining clinical outcomes [15–17]. Pre-existing conduction abnormalities such as right bundle branch block (RBBB), left bundle branch block (LBBB), and first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block do not appear to be significantly associated with procedural outcomes or short-term prognosis following BAV [18].

Our study supports these guidelines by demonstrating that BAV can be performed safely and effectively in an ASC and CSBU. Despite the ASC group having a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease and anemia, no significant differences were observed in critical outcomes such as in-hospital mortality, tamponades, significant bleeding, pseudoaneurysm formation, or pacemaker implantation between the two settings. Both ASC and CSBU showed substantial reductions in transvalvular gradients following the procedure. However, the relatively low number of adverse events – particularly in the ASC group – may have limited the ability to detect subtle or clinically relevant differences. These findings should therefore be interpreted with caution and considered exploratory. Nevertheless, they suggest that ASC can effectively handle BAV procedures and may help increase accessibility for patients with severe AS who do not have immediate access to surgical facilities, supporting BAV’s role in symptom relief and its continued use in clinical practice.

In contrast, anemia is considered a strong and independent risk factor for adverse outcomes following BAV. It has been associated with increased short-term and long-term mortality, likely reflecting impaired physiological reserve. However, in our analysis, the rates of death, myocardial infarction, bleeding, and transfusion following BAV were similar between both groups. Moreover, it is worth highlighting that despite a significantly higher proportion of anemic patients in the group where BAV was performed without on-site cardiac surgery backup, the overall complication rate remained low and comparable between groups.

Simultaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty and endovascular abdominal aortic repair has also been described as a successful approach in high-risk patients, further supporting the adaptability of BAV in complex scenarios [19].

Bularga et al. found that although significant hemodynamic and clinical improvements were observed at 30 days and 6 months, the mortality rate was 10.4% at 30 days, 21.6% at 6 months, and 28.3% at 12 months [20]. Major predictors of mortality included age, sex, initial LVEF below 20%, post-BAV LVEF below 30%, comorbidities, and urgency of the procedure. Many patients required repeat interventions, emphasizing BAV’s role as a bridging therapy [19, 20]. Kleczyński et al. found that in 49.4% of cases, BAV was performed as a bridge to TAVI, 6.9% as a bridge to SAVR, and 37.2% as rescue therapy. The 12-month mortality rate for rescue therapy was 66.9% [21]. BAV is also advantageous for patients undergoing urgent non-cardiac surgery, reducing perioperative risk and improving postoperative survival rates [22].

Studies provide valuable insights into various aortic valvuloplasty procedures. Vasquez et al. found that while periprocedural morbidity and mortality were similar across groups, the mortality rate at 6 and 12 months was significantly higher in patients undergoing BAV alone compared to those bridged to TAVI or undergoing TAVI directly [23]. A recent study on repeat TAVR with balloon-expandable valves found that the procedure effectively treated dysfunction of the initial TAVR with low complication rates. Clinical outcomes at 30 days and 1 year were comparable to native-TAVR, suggesting redo-TAVR as a viable option for selected patients [24].

Beyond procedural strategy, patient-specific factors may also influence outcomes. For example, large-scale analyses suggest that women undergoing BAV may experience lower in-hospital mortality compared to men, despite a higher incidence of vascular complications and transfusion requirements. These observations highlight the importance of sex-specific considerations when evaluating risk and choosing the appropriate treatment approach [25].

Despite advancements in TAVI, BAV plays an essential role, especially with new techniques such as transradial and bilateral balloon approaches, which have improved the procedure’s safety and efficacy [9]. Its lower cost and repeatability make BAV a practical choice, particularly in healthcare systems with limited resources. Ongoing research is necessary to refine BAV techniques, enhance patient selection criteria, and improve procedural outcomes. Integrating BAV with advanced treatments such as TAVI will be crucial for future cardiology practices [11].

In many randomized studies and meta-analyses, patients with high-risk aortic stenosis undergoing transfemoral TAVR were compared to those receiving balloon valvuloplasty before implantation versus a self-expanding valve without BAV. It was found that direct TAVR has a similar device success rate, need for postdilatation, and adverse events compared to balloon valvuloplasty before implantation. Subgroup analysis for balloon-expandable valves indicated a lower requirement for postdilatation in the direct TAVR group but a higher incidence of acute kidney injury and severe/life-threatening bleeding. The pooled results from randomized controlled trials showed an increased need for balloon post-dilatation in direct TAVR cases [26–29].

Some studies have also explored the potential impact of BAV on myocardial injury during the TAVR procedure, suggesting that omitting valvuloplasty might reduce myocardial damage and simplify the procedure. It has been proposed that avoiding BAV could reduce complications such as aortic regurgitation, systemic embolism, and annulus rupture. BAV can be useful for determining annular size and assessing the risk of coronary occlusion, particularly when the sinuses are low. However, with detailed assessment available through multislice computed tomographic angiography, it is possible to optimally select patients before TAVR, reducing the necessity of performing BAV during the procedure [30–32]. Moreover, recent data emphasize the importance of electrocardiographic and imaging predictors of conduction abnormalities and pacemaker implantation following TAVI, which may also affect procedural planning [33].

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective and single-center design limits the ability to establish causality and may affect the generalizability of the findings. Second, the relatively low number of adverse events, particularly in the ASC group, may have reduced the power to detect subtle differences between groups. Third, follow-up was limited to in-hospital outcomes, precluding conclusions about long-term safety and efficacy. Finally, patient selection was not randomized, and local practices and operator preference may have influenced decision-making.

Conclusions

BAV performed in ASC is just as safe and effective as that conducted in CSBU. Despite some baseline differences, key outcomes were similar between the two groups. Both groups showed significant improvements in post-procedure transvalvular gradients. This suggests that BAV can be safely and effectively conducted in standalone catheterization laboratories, providing a viable alternative for facilities without immediate surgical backup. Although promising, the results warrant validation in larger, prospective cohorts before this approach can be widely adopted.