Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a pathological condition characterized by a range of clinical and biochemical symptoms, resulting from an imbalance between the supply of oxygen and essential energy compounds to the heart muscle and its actual demand for them [1]. The predominant cause of this condition is the narrowing of the coronary arteries due to the progression of atherosclerotic process. Coronary heart disease is a chronic and progressive condition, however, it can suddenly transition to a life-threatening unstable state, which is most often a consequence of atherosclerotic plaque rupture or erosion [1–3].

The initial stage of atherosclerotic plaque formation is positive remodelling, during which the arterial walls thicken, while their diameter remains preserved. In contrast, the second stage is negative remodelling, during which the atherosclerotic lesion grows into the lumen of the arteries, causing reduced patency. Based on plaque location, a distinction is made between concentric and eccentric plaques. Concentric plaque is distributed around the entire circumference of the vessel, causing a persistent and progressive restriction of blood flow, while eccentric plaque covers part of the arterial circumference, leaving the uncovered fragment of arterial wall highly responsive to external stimuli. In addition, a distinction between stable and unstable atherosclerotic plaques is also made. The stable form is characterized by a low lipid content, located beneath the vascular endothelium with a thick fibrous cap protecting it from rupture. An unstable atherosclerotic plaque, on the other hand, has a large lipid core covered by a thin fibrous layer. Increased inflammatory processes within it, with a predominant destructive role of macrophages and lymphocytes, can lead to plaque erosion and rupture [1, 4].

Classic risk factors for CHD, which affect both sexes, include non-modifiable factors such as genetic predisposition and age (over 55 years in women, and over 45 years in men) and modifiable factors, i.e. hypertension, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, obesity, vascular endothelial inflammation and dysfunction, abnormal lipid profile (increased low-density lipoprotein – LDL, and triglyceride fractions, decreased high-density lipoprotein – HDL), homocysteinaemia, and those related to unhealthy behaviours, i.e. smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, chronic stress, and poor diet [3, 5, 6]. There are also female-specific risk factors for CHD, including menopause and premature menopause (both natural and artificially induced), the use of hormonal contraceptives, and certain conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome. Risk factors also include psychological aspects, e.g. depression and anxiety, as well as low educational attainment and low socio-economic status [5, 6].

Depending on the variation in clinical features, a distinction is made between chronic and acute coronary syndromes (ACS). Chronic coronary syndromes (CCS), also known as stable syndromes, include the typical chronic coronary syndrome (stable angina) and angina without significant coronary artery stenosis: coronary microvascular disease (microvascular angina), myocardial bridge angina, and Prinzmetal angina (variant angina pectoris). The cause of stable coronary artery disease is the presence of a permanent and significant stenosis (50–80% in diameter) of the arterial lumen, resulting in reduced perfusion pressure and blood flow downstream of the stenosis site. This becomes particularly important during physical exertion, when there is a three- to six-fold increase in myocardial oxygen demand. The resulting myocardial hypoxia due to this imbalance leads to the appearance of symptoms, the most common of which is localized chest pain, felt as pressure or heaviness, which may also present as a burning, pressing, or squeezing sensation. Typically, the pain is localized behind the breastbone, with frequent radiation to the neck, jaw, back, left shoulder, and epigastrium. It usually subsides within 1–3 minutes after taking nitroglycerin or within a few minutes of rest (up to 20 minutes). In addition to physical exertion, pain can be triggered by various factors such as intense emotional stress, cold air, or a heavy meal [1, 2]. Women, compared to men, report typical chest pain symptoms less frequently. Symptoms of CHD in women are more often characterized by breathlessness, weakness, and a pre-syncope/syncope state, with pain located atypically, e.g. in the epigastrium or back. They may also experience dizziness, visual disturbances, and nausea/vomiting. These uncharacteristic or less severe symptoms often lead to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis of CHD in women, especially at the primary care level [1, 6, 7].

Atypical stable coronary syndromes include coronary microvascular disease (formerly known as cardiac syndrome X), which particularly affects postmenopausal women. It is likely caused by impaired vascular endothelial function due to decreased nitric oxide availability and increased endothelial cell production and sensitivity to endothelin-1 (ET-1). The causes of this disorder are believed to include oestrogen deficiency associated with menopause, as well as hyperlipidaemia, smoking, and chronic vascular endothelial inflammation. A large proportion of patients suffering from this type of CHD are individuals with diagnosed depression, anxiety disorders, or a hypochondriacal personality. Microvascular ischaemic angina is characterized by ST-segment depression on exercise electrocardiography and normal coronary artery visualization on coronary angiography. Its symptoms mainly occur after exercise and may be prolonged, lasting up to 15–20 minutes. The administration of nitroglycerin does not provide significant pain relief [1, 8]. The main aim of CCS treatment is to reduce mortality and improve patients’ quality of life. The basic principles of therapy include minimizing atherosclerotic risk factors, managing comorbidities that may aggravate angina (e.g. anaemia, cardiac arrhythmias), increasing physical activity, regular annual influenza vaccination, pharmacological treatment, and invasive procedures [2, 9].

Acute coronary syndrome is caused by a sudden imbalance between oxygen supply and demand in myocardial cells. The patient’s clinical presentation, biochemical markers of myocardial damage, and electrocardiogram findings allow ACS to be classified into non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome, which includes unstable angina (UA) and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (STEMI). The former is caused by a recent or worsening restriction in coronary blood flow, while NSTEMI is specifically induced by damage to an eccentrically located atherosclerotic plaque and the formation of a thrombus on its surface. This results in a small, usually subendocardial, area of myocardial necrosis [1, 2]. In contrast, the main cause of STEMI is rupture of the atherosclerotic plaque cap (in 75% of cases), leading to the release of embolic material and complete occlusion of the vessel lumen [1, 2]. The characteristic symptom of UA/NSTEMI is chest pain or worsening of previously stable angina symptoms. The pain persists despite taking nitroglycerin or stopping physical activity, lasts longer, and may also occur at rest. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction most often develops in the morning, and its main symptom is severe, escalating chest pain of a crushing, burning, or pressing nature. It appears suddenly, lasts longer than 20 minutes, and does not subside with nitroglycerin or rest. Signs of myocardial infarction also include a rapid drop in blood pressure with compensatory tachycardia (cardiogenic shock), weakness, fainting, severe anxiety or fear of death, excessive sweating, shortness of breath, and jugular vein distension, indicative of progressive acute heart failure [1, 2, 10]. Clinical features of ACS in women are often atypical. They may present with palpitations and pain radiating to the left arm, back, neck, or jaw, along with non-specific symptoms such as dyspeptic complaints, nausea/vomiting, epigastric pain, fatigue, or breathlessness. The uncharacteristic presentation of myocardial infarction symptoms in women contributes to delayed diagnosis, hospitalization, and interventional treatment, resulting in a poorer prognosis [2, 5, 10].

The first crucial diagnostic method in CHD is resting electrocardiography. The next immediate step is blood analysis to assess myocardial necrosis markers: cardiac troponins, consisting of three subunits – troponin I, troponin T, and troponin C – as well as creatine kinase-MB levels. Useful and recommended specialized investigations include resting transthoracic echocardiography, differential chest X-ray, cardiac perfusion scintigraphy (single-photon emission computed tomography), and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. The key invasive method for visualizing coronary artery changes is coronary arteriography [1, 2, 11].

Modern pharmacotherapy and effective interventional treatment have contributed to improving the prognosis of patients during their hospital stay. However, the post-hospital period is still associated with a significant risk of heart attack and death. Patients with CHD should attend follow-up visits to assess the presence of symptoms and monitor their adherence to preventive measures and pharmacological treatment [2, 12].

The aim of CHD prevention is the early detection of modifiable risk factors. For this reason, adjustments should be made to the patient’s lifestyle and health behaviours. Health behaviours are actions undertaken by an individual which have a direct or immediate positive or negative impact on maintaining health, both in the physical and mental domains. There are two types of health behaviours. The first, called pro-health behaviours, have a positive effect on health, help prevent disease, and promote good recovery. The second type, anti-health (self-destructive) behaviours, has a negative impact, contributing to more frequent and more severe physical and mental disorders, as well as the development of abnormalities. Examples of health-promoting behaviours include avoiding stimulants, ensuring traffic safety (e.g. wearing seat belts while driving), healthy eating habits (e.g. minimising the consumption of fatty acids and carbohydrates, and eating foods rich in fibre, minerals, and vitamins), positive health practices (e.g. maintaining personal hygiene and engaging in physical exercise), and preventive measures (e.g. regular check-ups and vaccinations). Unhealthy behaviours include the use of stimulants (such as smoking and alcohol consumption) or other psychoactive substances. People who engage in self-destructive behaviours are often characterised by low self-esteem, emotional immaturity, difficulty expressing feelings, and low stress tolerance [2, 12, 13].

Menopause (climacterium) is a natural physiological process occurring between the reproductive period and old age, during which the cyclical functioning of the ovaries ceases. Its main stage is menopause itself, which marks the last menstrual period, after which there has been no bleeding for at least 12 consecutive months. In Western European countries, including Poland, the average age of menopause is estimated at 50 years. The timing of the last menstruation is an important indicator of women’s health, as the overall mortality rate among women decreases with the age at which menopause occurs [14]. The decrease in oestrogen levels, typical during the climacteric period, is significantly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, including CHD. Until menopause, high oestrogen levels exert a protective effect on the cardiovascular system. By stimulating the enzyme nitric oxide synthase (NOS), they increase the production and bioavailability of the vasodilator nitric oxide, preventing the development of atherosclerosis and, consequently, CHD. These changes are accompanied by a decrease in the production of prostacyclin, which acts similarly to nitric oxide, and an increase in the secretion of the vasoconstrictor ET-1. As a result, blood flow within the vascular system is reduced. For this reason, women tend to develop this disease about 10 years later than men [7].

As a result of hormonal changes observed during menopause, women also experience an increase in LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol levels in the blood serum. Blood vessels age at an accelerated rate, mainly due to the destruction of collagen fibres and fibrosis of the basement membrane, which results in stiffening of the arterial walls and the development of hypertension [15]. There is a widespread belief among the general public that CHD is a problem that mainly affects men, but the reality is different. In fact, women suffer from this disease more often. Statistics show that young women are increasingly being hospitalized due to the main complication of CHD – myocardial infarction. For this reason, in 2019 in Poland, one in four women (25.9% of all deaths) died from a heart attack, making it the leading cause of death among women in the country. According to global burden of disease data, in the same year, 95,000 women and 79,000 men died from cardiovascular diseases – not only myocardial infarction – which accounted for 48.6% of total deaths among women and 37.8% among men [5].

The aim of the research was to determine the level of knowledge about CHD among women in the perimenopausal age and to compare this knowledge, particularly regarding risk factors, with the health behaviours undertaken by the respondents.

Material and methods

The study was carried out between 1 February and 30 April 2023, and the study group consisted of women in the perimenopausal period, i.e. between 45 and 65 years of age. Data were collected using a diagnostic survey method, and the research tools included an original questionnaire and Zygfryd Juczyński’s standardized health behaviour inventory (inwentarz zachowań zdrowotnych – IZZ). Before completing the questionnaire, each woman surveyed was informed about the purpose of the study and assured of anonymity and voluntary participation. The research was conducted using the CAWI method, by distributing the questionnaires via popular social media platforms to users associated with the following thematic groups: Menopause – support group, Menopause – group moderated by gynaecologist Marek Kaczmarczyk, and Women and menopause. The original questionnaire consisted of multiple-choice questions concerning definitions, risk factors, causes, symptoms, complications, and preventive methods, as well as methods of diagnosing CHD.It also included true/false questions. Juczyński’s IZZ was used to determine the overall intensity of health-promoting behaviours and to assess the severity of individual components of these behaviours. The following aspects were assessed: proper dietary habits, health practices, preventive behaviours, and positive mental attitude. Respondents indicated the frequency with which they performed the listed activities using a five-point scale, with the following response options: almost never (1 point), rarely (2 points), occasionally (3 points), often (4 points), and almost always (5 points) [16]. The numerical values indicated by the respondents were summed to obtain an overall indicator of the intensity of health behaviours. Its value is 24–120 points, with a higher score indicating a greater intensity of health-promoting behaviours. After conversion into standardised units, the overall index was interpreted using a sten scale. Results within the range of 1–4 stens are considered low, 5–6 stens as average, and 7–10 stens as high. In addition, the intensity of each of the four categories of health behaviours – each of 16–30 points – was calculated separately. In this case, the indicator is the mean score (M) obtained. Statistical analysis was performed using Excel and the Jamovi statistical package. The significance level was set at α = 0.05, so results with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The following methods were used for statistical analysis: descriptive statistics, which were used to characterise the distribution of quantitative variables, and frequency analysis, i.e. the percentage distribution of qualitative variables. To assess the conformity of the observed distribution with the theoretical distribution, the χ2 goodness-of-fit test was used. Fisher’s exact test was also applied to assess the relationship between two nominal variables in small groups. The use of Spearman’s rho monotonic correlation coefficient allowed for the assessment of the strength and direction of the monotonic relationship between two variables.

Characteristics of the study group

The study involved 262 women in the perimenopausal period (aged 46–65). Most of the respondents were aged 46–50 (n = 109; 41.6%), 28.2% (n = 74) were aged 51–55, while the smallest group included women aged 61–65 (n = 28; 10.7%). The largest group of respondents (n = 91; 34.7%) indicated a town with up to 50,000 inhabitants as their place of residence. The next largest group included women living in rural areas, accounting for 32.8% (n = 86) of the respondents, while the smallest group (n = 17; 6.5%) included women living in a city with a population of 150,000–500,000 inhabitants. The majority of respondents (n = 159; 60.7%) were employed in white-collar jobs, while women in blue- collar jobs accounted for 39.3% (n = 103) of the study participants. The largest group of respondents had higher education (n = 116; 44.3%), followed by those with secondary education (n = 110; 42.0%). Vocational education was held by 12.2% (n = 32) of respondents, and primary education was the least common (1.5%, n = 4). Over three-quarters of the women surveyed (n = 204; 77.9%) declared that they were married or in an informal relationship. Divorced women accounted for 10.7% (n = 28), widows for 6.9% (n = 18), and single women for 4.6% (n = 12) of the respondents. The vast majority of participants did not use hormone replacement therapy (HRT) (n = 238; 90.8%), while the remaining respondents were undergoing such therapy (n = 24; 9.2%). More than three-quarters of the respondents had never been treated by a cardiologist (n = 203; 77.5%), while women who had been diagnosed with or suspected of having CHD and were therefore under the care of a specialist accounted for 7.3% (n = 19) of the respondents.

A detailed description of the study group is presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics of the study group

Results

Knowledge of women in the perimenopausal age about the definition, risk factors, causes, symptoms, complications, preventive and diagnostic methods of coronary heart disease

According to the largest group of respondents (n = 186; 71%), CHD involves a reduced oxygen supply to the heart, and simultaneously, 64.5% (n = 169) of participants believe that it is caused by narrowing of the coronary arteries. Notably, 40.1% (n = 105) of respondents indicated heart rhythm disorders, 29.8% (n = 78) marked increased blood pressure, and 18.7% (n = 49) identified weakened heart contractility as the nature of CHD.

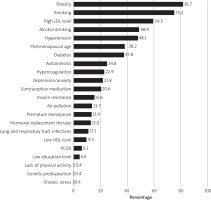

The most frequently reported risk factors for CHD in women, as indicated by the survey participants, included obesity (n = 214; 81.7%), smoking (n = 197; 75.2%), high LDL cholesterol (n = 156; 59.5%), alcohol consumption (n = 128; 48.9%), high blood pressure (n = 126; 48.1%), postmenopausal age (n = 100; 38.2%), and high glucose levels (diabetes) (n = 99; 37.8%). Other factors received fewer than 30% of responses and included hypercoagulation (n = 60; 22.9%), depression and anxiety (n = 57; 21.8%), insulin resistance (n = 40; 15.6%), and respiratory tract and pneumonia infections (n = 29; 11.1%). Hormone replacement therapy was identified as a risk factor for CHD by 13% (n = 34) of respondents. All risk factors identified by the respondents are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Respondents’ awareness of risk factors for coronary heart disease

HDL – high-density lipoprotein, LDL – low-density lipoprotein, PCOS – polycystic ovary syndrome Multiple responses were allowed; therefore, the total percentage exceeds 100.

The research participants correctly identified atherosclerosis (n = 178; 67.9%) as the most common direct cause of CHD. They also mentioned hypertension (n = 120; 45.8%), coronary artery inflammation (n = 79; 30.2%), thrombosis (n = 77; 29.4%) and diabetes (n = 43; 16.4%).

According to the respondents, the main symptoms of CHD include shortness of breath and difficulty breathing (n = 163; 62.2%), widespread chest pain (n = 152; 58%), and pain behind the breastbone radia- ting to the left arm (n = 111; 42.4%). Although reported less frequently, other symptoms mentioned by women included sudden loss of consciousness (n = 82; 31.3%), sudden and rapid pounding of the heart (n = 79; 30.2%), nausea and vomiting (n = 64; 24.4%), and epigastric pain (n = 45; 17.2%). In the opinion of the largest group of respondents, CHD symptoms may appear during or after emotional distress (n = 171; 65.3%), after physical exertion (n = 149; 56.9%), and as a result of experiencing severe anxiety (n = 139; 53.1%).

For the majority of respondents (n = 201; 76.7%,), myocardial infarction was identified as the most prevalent complication of CHD. A substantial proportion of women also reported heart failure (n = 159; 60.7%) and cardiac arrhythmias (n = 104; 39.7%) as notable clinical manifestations. Furthermore, thromboembolic events, including stroke (n = 98; 37.4%) and pulmonary embolism (n = 59; 22.5%), were frequently indicated.

According to the most numerous group of research participants, the main preventive activities for CHD included engaging in regular physical activity (n = 209; 80.1%), abstaining from smoking (n = 205; 78.5%), avoiding alcohol consumption (n = 165; 63.2%), and, less frequently, consuming vegetable fats (n = 98; 37.5%) and limiting the intake of sweets and salty snacks (n = 143; 54.8%).

When asked about diagnostic methods for CHD, respondents most frequently indicated echocardiography (n = 209; 79.8%) and resting electrocardiography (n = 185; 70.6%). A smaller proportion of women selected coronary angiography (n = 98; 37.4%), physical examination involving chest auscultation (n = 49; 18.7%), blood tests (n = 41; 15.6%), and troponin level assessment (n = 40; 15.3%) as relevant diagnostic procedures.

For each correct answer in the multiple-choice section, one point was awarded, whereas incorrect responses received zero points, resulting in a maximum attainable score of 45 points. To assess the respondents’ level of knowledge, a point-to-percentage scale was applied, in which: 0–25% correct responses (0–11 points) indicated a lack of knowledge, 26–50% (12–22 points) reflected a low level of knowledge, 51–75% (23–33 points) corresponded to a good level of knowledge, and 76–100% (34–45 points) denoted a high level of knowledge.

As presented in Table 2, the women participating in the study achieved an average score of 18.82 points (SD = 7.390), corresponding to an average percentage of 41.82% (SD = 16.423). The most frequently observed level of knowledge among respondents was low (n = 144; 55%), while 16.8% (n = 44) of participants demonstrated a complete lack of knowledge. A good level of knowledge was recorded in 24.8% (n = 65) of respondents, and only 3.4% (n = 9) achieved results indicative of a high level of knowledge regarding CHD.

Knowledge of women in the perimenopausal age regarding differences in the incidence of coronary heart disease between women and men, and the impact of female sex hormones and hormone replacement therapy on the progression of this disease

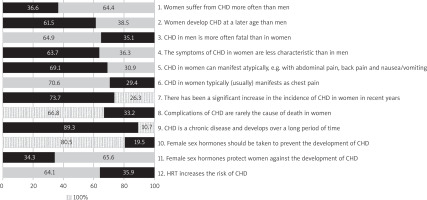

In this section of the results, the true/false statements were analysed and are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Respondents’ knowledge of the specific course of coronary heart disease in women and its differences compared to men

CHD – coronary heart disease, HRT – hormone replacement therapy Responses were based on true/false statements; “True” answers are presented in the first column and “False” answers in the second column of the graph. Correct responses are indicated in black.

Firstly (Statement 1), respondents were asked whether the statement Women suffer from coronary heart disease (CHD) more often than men is true. Only 36.6% (n = 96) of respondents indicated that it was true, while the majority (n = 166; 63.4%) considered it false.

More than half (n = 161; 61.5%) of participants correctly identified the statement (Statement 2) Women develop CHD at a later age than men as true. In Statement 3, respondents assessed whether CHD in men is more often fatal than in women is true. As in the first question, the majority (n = 170; 64.9%) incorrectly identified this statement as true.

In contrast, most respondents (n = 167; 63.7%) correctly agreed with the statement (Statement 4) that The symptoms of CHD in women are less characteristic than in men.

In Statement 5, women were asked whether CHD in women can manifest atypically, e.g., with abdominal pain, back pain, and nausea/vomiting. The majority (n = 181; 69.1%) correctly identified this statement as true. Despite these responses, 70.6% (n = 185) of participants agreed with the next affirmative statement (Statement 6): CHD in women typically (usually) manifests as chest pain. In Question 7, respondents assessed the statement There has been a significant increase in the incidence of CHD in women in recent years. Almost three-quarters (n = 193; 73.7%) correctly agreed with this statement. The majority (n = 175; 66.8%) of participants considered the statement (Statement 8) Complications of CHD are rarely the cause of death in women to be false.

Question 9 presented the statement CHD is a chronic disease and develops over a long period of time. Most respondents (n = 234; 89.3%) correctly agreed with this statement.

Question 10 asked whether Female sex hormones should be taken to prevent the development of CHD. The vast majority (n = 211; 80.5%) correctly identified this statement as false. Statement 11, Female sex hormones protect women against the development of CHD, was accepted by only 34.4% (n = 90) of respondents. In the final question (Statement 12), the majority (n = 168; 64.1%) agreed that the statement HRT increases the risk of CHD is false.

Statements 1–9 concerned the specific characteristics of CHD in women and differences in the incidence of this disease between women and men. Respondents received 1 point for each correct answer. Out of a possible 9 points, the women participating in the survey achieved an average score of 5.25 (SD = 1.572), corresponding to 58.35% (SD = 17.472) (Table 3). The largest proportion of surveyed women scored 6 points (n = 64; 24.4%), while 21% (n = 55) scored 5 points, and 4 and 7 points were obtained by the same number of respondents (n = 47; 17.9%). Only 3 women (n = 1.1%) achieved the maximum score.

Table 3

Descriptive statistics summarising respondents’ knowledge of the specific course of coronary heart disease in women and its differences in occurrence between women and men

| Parameters | N | M | SD | Me | Min | Max | Ske | Kur |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge (points) | 262 | 5.25 | 1.572 | 5.00 | 1.00 | 9.00 | –0.26 | –0.29 |

| Knowledge (%) | 262 | 58.35 | 17.472 | 55.56 | 11.11 | 100.00 | –0.26 | –0.29 |

To determine women’s knowledge about the role of sex hormones and the use of HRT in the development of CHD, respondents could obtain 3 points (Statements 10–12). The survey participants achieved an average score of 1.79 (SD = 0.598), corresponding to 59.67% (SD = 19.946) (Table 4). The majority (n = 163; 62.2%) of surveyed women scored 2 out of 3 points. The remaining scored 1 point (n = 74; 28.2%), 3 points (n = 23; 8.8%), or 0 points (n = 2; 0.8%).

Table 4

Descriptive statistics summarising respondents’ knowledge of the role of female sex hormones and the use of hormone replacement therapy in the prevention and development of coronary heart disease

| Parameters | N | M | SD | Me | Min | Max | Ske | Kur |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge (points) | 262 | 1.79 | 0.598 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | –0.10 | –0.05 |

| Knowledge (%) | 262 | 59.67 | 19.946 | 66.67 | 0.00 | 100.00 | –0.10 | –0.05 |

According to the criteria used earlier, the average scores were classified into one of four categories defining the level of knowledge: lack, low, good, and high. In both areas studied, the results fell into the category of good knowledge level. Next, we analysed whether respondents’ knowledge about the role of sex hormones and HRT in the development of CHD was associated with age, place of residence, and education level (Table 5). The analysis of relationships between variables was preceded by a check of the assumption for the χ2 test regarding sufficiently large expected frequencies (all expected values > 1; 80% of expected values > 5). This condition was not met for any variable pair; therefore, Fisher’s exact test was used, which did not indicate a significant relationship between respondents’ knowledge and their age, place of residence, or education level (Table 6). To examine the direct correlation and determine the strength and direction of relationships between the studied variables, Spearman’s rho was also applied. The results of this analysis likewise did not indicate any significant relationships between demographic data or education level and respondents’ knowledge (Table 7).

Table 5

Associations between respondents’ age, place of residence, and level of education and their knowledge of the role of female sex hormones and the use of hormone replacement therapy in the prevention and development of coronary heart disease

Table 6

Fisher’s exact test results assessing the association between respondents’ age, place of residence, and level of education and their knowledge of the role of female sex hormones and the use of hormone replacement therapy in the prevention and development of coronary heart disease

| Parameters | N | p-value | Cramer’s | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age | 262 | 0.994 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Place of residence | 262 | 0.594 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Level of education | 262 | 0.867 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Table 7

Spearman’s rho correlation analysis examining the association between respondents’ age, place of residence, and level of education and their knowledge of the role of female sex hormones and the use of hormone replacement therapy in the prevention and development of coronary heart disease

| Parameters | N | rho | 95% CI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 (points) | Lower Upper | ||||

| Place of residence | Knowledge | 262 | 0.06 | –0.06 | 0.19 | 0.312 |

| Level of education | Knowledge | 262 | 0.04 | –0.08 | 0.16 | 0.513 |

| Age | Knowledge | 262 | 0.00 | –0.12 | 0.13 | 0.981 |

Health behaviours of women in the perimenopausal age and their correlation with the current level of knowledge about risk factors for coronary heart disease

According to data obtained from the analysis of the IZZ developed by Juczyński, most (n = 107; 40.8%) of the women surveyed achieved average scores on the questionnaire. Low scores were recorded for 34.7% of respondents (n = 91), while fewer than 25% (n = 64) of women obtained high scores, indicating that only a quarter of respondents exhibit health behaviours with a strong positive impact on health. An analysis of the mean (M) values for the four categories of the IZZ showed that respondents scored within the average range in each category, i.e.: correct eating habits – M = 20.93 (SD = 4.573), preventive behaviours – M = 20.94 (SD = 4.396), positive mental attitude – M = 21.11 (SD = 4.186), health practices – M = 19.77 (SD = 4.007).

Basic descriptive statistics for the overall results of the IZZ and its four categories are presented in Table 8, while Table 9 shows statistics for responses to all individual health behaviour items.

Table 8

Descriptive statistics of the health behaviour inventory, including overall scores and scores across four primary subcategories

Table 9

Descriptive statistics summarising respondents’ answers to individual items of the health behaviour inventory

The highest mean values were recorded for the statements: I have friends; my family life is stable (M = 4.19, SD = 1.003) and I limit my smoking (M = 4.02, SD = 1.531), while the lowest were observed for: I avoid overworking (M = 2.75, SD = 1.092) and I avoid excessive physical exertion (M = 3.02, SD = 0.973).

In order to verify the relationship between the surveyed women’s knowledge about the risk factors for CHD and the results obtained from the previous analysis of the IZZ developed by Juczyński, an analysis of the relationship between nominal variables was conducted (Table 10). This was verified using the χ2 association test, assuming sufficiently large expected frequencies (all expected values > 1; 80% of expected values > 5). This condition was met, and the result of the χ2 test did not indicate any significant relationships between women’s knowledge of risk factors for CHD and their health behaviours (Table 11).

Table 10

The association between respondents’ knowledge of coronary heart disease risk factors and their health-related behaviours, as interpreted from the health behaviour inventory results

Table 11

Results of the χ2 test assessing the association between respondents’ knowledge of coronary heart disease risk factors and their health-related behaviours, as interpreted from the health behaviour inventory among surveyed women

| Parameters | N | χ 2 | df | p-value | Cramer’s | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Health behaviour inventory results | 262 | 7.7 | 6 | 0.258 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.14 |

Discussion

No comprehensive studies have been conducted to date in Poland to assess the knowledge of women in the perimenopausal age regarding the importance, causes, symptoms, complications, and diagnostic and preventive methods of CHD. Our study revealed that the level of knowledge among the surveyed women was predominantly low (55%), with only 24.8% and 3.4% of respondents reporting good and very good knowledge, respectively. Olszanecka, a Polish expert in cardiovascular disease and one of the authors of the report prepared by The Lancet Women and Cardiovascular Disease Commission in 2021, stated that women’s awareness of cardiovascular disease is at an increasingly low level [5]. For example, in 2009, 65% of respondents indicated these diseases as the main cause of death in women, while in 2019, the percentage of such responses decreased to 44% [5]. Similar findings emerged from our own analysis, in which the majority of women (66.8%) believed, among other things, that complications of CHD are rarely the cause of death in women.

The respondents’ knowledge regarding the nature of CHD was considerably better, as 71% of respondents believed that the disease is associated with a reduced supply of oxygen to the heart, and 65% understood it as a narrowing of the coronary arteries. In the study conducted by Krzyżanowska et al. among students at the Medical University of Lublin, as many as 94.5% of respondents knew the correct definition of CHD, although it should be noted that this knowledge may have been acquired during their coursework [17]. In another study conducted by Sawicka et al. on a group of patients after myocardial infarction (40% of whom were women), the majority of respondents correctly identified atherosclerosis as the primary cause of CHD [18]. Comparable results (approximately 68% of respondents) were obtained in our own study. The aforementioned study by Sawicka et al. also examined patients’ knowledge of CHD risk factors. Respondents accurately, although to a limited extent, identified diabetes (20%) and high blood cholesterol levels (17%) as such. Overweight/obesity, stress, and smoking were each indicated by 16% of respondents, while the least frequently selected risk factor was low physical activity (15%) [18]. Research in this area was also carried out by Krzyżanowska et al. among medical university students. In this study, students demonstrated a higher level of knowledge, most frequently indicating age (93.5%), smoking (87%), hypertension (86.5%), followed by genetic factors (84%) and diabetes (79%). According to the results, female respondents demonstrated a higher level of knowledge about CHD risk factors compared to male participants [17]. The conclusions from the above studies are partially consistent with the responses obtained in our study, in which the most frequently indicated risk factors were obesity (81.7%), smoking (75.2%), high LDL cholesterol levels (59.5%), alcohol consumption (48.9%), and hypertension (48.1%). In contrast, responses such as diabetes, hypercoagulability, or postmenopausal age were selected by fewer than 40% of participants. Similarly, a study conducted by Dziedzic et al. among patients treated at a cardiology clinic showed that respondents had a low level of knowledge, particularly regarding diabetes as a risk factor for CHD. The authors, unlike in our study, indicated that genetic factors have a greater impact on the development of CHD than lifestyle-related factors [19].

In our analysis of respondents’ knowledge regarding the main symptoms of CHD, we found that half of them responded correctly, indicating shortness of breath and difficulty breathing (62.2%), widespread chest pain (58%), and pain behind the breastbone radiating to the left arm (42.4%). A comparable study was conducted by Rasool et al., who assessed knowledge of CHD symptoms among patients admitted to hospital for various reasons. In that study, the most commonly reported symptoms were chest pain (42%), arm and back pain (23%), and profuse sweating (19%) [20]. In our study, the majority of respondents (69.1%) correctly stated that CHD in women can manifest as abdominal pain, back pain, and nausea/vomiting. A slight majority (63.7%) also believed that the symptoms of CHD in women are less characteristic than in men, which contradicts the analysis of another question, in which about half of respondents (58%) incorrectly stated that CHD in women usually manifests as chest pain. Partially consistent findings were reported by Ferry et al., who compared the symptoms of myocardial infarction in men and women. Their study showed that women more often reported pain radiating to the left arm, back, neck, or jaw. Nausea and heart palpitations were also common symptoms among the women analyzed [10]. In contrast, a study conducted by Khan et al. demonstrated that myocardial infarction in women is more likely to occur without chest pain compared to men [21].

Our research has shown that women’s knowledge about the role of female sex hormones and the use of HRT in the development of CHD is moderate. Slightly more negative findings were reported by Smail et al. in a study conducted among women from the United Arab Emirates. Their research indicated that participants had limited awareness of the increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease after menopause [22]. This finding is consistent with our own analysis, in which 65.6% of surveyed women incorrectly indicated that female sex hormones have no protective effect against the development of CHD, and only 40% correctly identified postmenopausal age as a CHD risk factor. Research conducted in Saudi Arabia by Albaqami et al. provides valuable insights into women’s knowledge of the impact of HRT on cardiovascular disease [23]. It was shown that 19.3% of respondents believed that HRT reduces the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, 9.7% disagreed, while as many as 71% had no opinion. When asked whether taking female sex hormones increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, 10.7% of respondents answered affirmatively, 11.5% considered this false, and 77.8% did not know the answer. In summary, the analysis of Albaqami et al.’s results indicates that participants lacked knowledge in the area under study [23]. The findings of Albaqami et al. contradict our results, in which 64.1% of respondents correctly stated that HRT does not increase the risk of CHD, and the vast majority (80.5%) correctly indicated that taking female sex hormones does not protect against its development [23].

The appropriateness of HRT in postmenopausal women, in the context of the potential risk of cardiovascular disease, has been the subject of numerous studies. However, the recommendations and safety of HRT remain controversial [24, 25]. A publication by Lesiak et al. and a meta-analysis by Lobo et al. presented a review of the available and current literature on this topic [25, 26]. The first studies conducted in the 1990s demonstrated the beneficial effects of HRT on cardiovascular disease risk. Similarly, subsequent observations from the nurses’ health study confirmed the cardioprotective effects of this therapy in both primary and secondary prevention. Another study aiming to verify these earlier findings was the heart and oestrogen/progestin replacement study. Unfortunately, this study challenged the previously emphasized preventive role of HRT. Its results revealed, for the first time, that the use of oestrogen-progestogen HRT is not safe and may increase the risk of thromboembolic events. A study conducted by the women’s health initiative (WHI) also questioned the efficacy and safety of this therapy. According to WHI findings, the incidence of thromboembolic disease, stroke, and myocardial infarction increased among women using HRT, leading to the conclusion that this therapy should not be used for primary prevention of CHD. However, subsequent studies have shown that initiating oestrogen therapy within 10 years of menopause onset may offer several benefits, including a reduced risk of death, myocardial infarction, and colorectal cancer. Another study, presented in 2003 by Lobo et al., investigated the effect of HRT on the progression of atherosclerosis in blood vessels. It was found that taking female hormones during menopause does not inhibit the progression of atherosclerotic changes, and therefore, according to the authors, cannot exert a protective effect against CHD. However, further studies published in 2007 by the WHI and in 2011 by the women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation concluded that early initiation of HRT during the perimenopausal period may be associated with a reduced risk of CHD, compared to women who started treatment later after the onset of menopause. A subsequent study by Harman et al., similar to that by Lobo et al., again demonstrated that early initiation of HRT does not inhibit the progression of atherosclerosis, and only slightly improves cardiovascular risk markers. In 2015, a meta-analysis by Boardman et al., published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, concluded that HRT is not recommended as a preventive measure for cardiovascular disease. Taking into account all the above findings, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists published a position statement indicating that HRT should not be used as a preventive intervention, but that early initiation of therapy – within 10 years of the last menstrual period or before the age of 60 – significantly reduces mortality and the risk of developing CHD [25–28]. Consistent with this review, the women surveyed in our study correctly recognized that HRT does not increase the risk of CHD, but also does not protect against it. Our analysis showed no correlation between women’s knowledge of the role of sex hormones and the use of HRT, and their age, place of residence, or level of education. Hamid et al. reached different conclusions. According to their results, knowledge about the relationship between the onset of menopause or the use of HRT and CHD was associated with the respondents’ level of education [29]. In turn, a study by Doamekpor et al. demonstrated that the likelihood of a high level of knowledge about the role of HRT in the development of CHD increased with age [30]. Observations by Jin et al. showed that knowledge about the potential protective effect of female sex hormones was associated with menopause onset, social status, and occupation [31]. An observation by Rasool et al. showed that the level of knowledge about CHD symptoms did not depend on the presence of the disease [20]. This finding is comparable to our results, which also showed no correlation between the level of knowledge among patients with CHD and their referral to specialist cardiological care.

Analysing the results of Juczyński’s IZZ, we found that the overall average health behaviour score, as well as the scores obtained in each of the four categories, were at a moderate level. Similar conclusions were drawn by Weber-Rajek et al. in their study assessing the health behaviours of women, including those in the perimenopausal period [32]. Identical findings were also reported by Kurowska and Kierzenkowska [33], and a similar observation was made by Asrami et al., although they used the Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile II as the research tool. Their study showed that women in the menopausal period exhibited moderate health-promoting lifestyle behaviours [34]. Our own analysis showed no correlation between the knowledge of women in the perimenopausal period regarding CHD risk factors and their health behaviours. Similar conclusions were reached by Sawicka et al. in their study involving individuals who had experienced myocardial infarction [18]. In a study by Buraczyński and Gotlib, which examined the level of knowledge among patients undergoing coronary angioplasty regarding CHD risk factors, comparable results were obtained. According to their findings, a discrepancy was observed between the high level of knowledge presented by respondents about the impact of lifestyle on CHD risk and the presence of multiple risk factors for the disease [35]. Kawalec et al. also reached similar conclusions. Their study was conducted exclusively among women in white-collar professions, aged 20–59. The results showed that the respondents had a satisfactory level of knowledge about a healthy lifestyle and were aware of their health status; however, most of them exhibited modifiable risk factors that increased the likelihood of developing CHD [36].

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the large number of respondents whose answers were analysed, as well as the data collected from women aged 45–65, which covers a broad age range within the perimenopausal period. Another strength is the use of Juczyński’s standardized IZZ, a validated research tool. However, the study has certain limitations, including the recruitment of participants exclusively through social media platforms. This method may have introduced selection bias, as it likely excluded women without internet access or those less active online, potentially limiting the representativeness of the sample.

Future research should be expanded to include additional methods of data collection.

Conclusions

The respondents most frequently demonstrated a low level of knowledge regarding the essential characteristics, risk factors, causes, symptoms, complications, prevention, and diagnostic methods of CHD. However, they presented a good level of knowledge concerning the differences in the incidence of CHD between women and men.

The research participants demonstrated a good level of knowledge about the role of sex hormones and HRT in the development of CHD. Nevertheless, no correlation was found between the level of this knowledge and the age, place of residence, or education level of the women surveyed.

Moreover, no correlation was observed between the respondents’ knowledge of CHD risk factors and their health behaviours. This finding suggests a continued need to educate women – particularly those in the menopausal period – about CHD risk factors and appropriate health-promoting behaviours.