Introduction

The carbohydrate-restricted diets are becoming increasingly popular among the general population, as well as among obese and insulin-resistant individuals, and patients with both type 2 and type 1 diabetes (T1D), including adolescents and children. There are several types of these diets: low-carbohydrate diets (LCD), in which carbohydrates constitute < 26% of the total energy intake; very low-carbohydrate diets (VLCD), in which carbohydrates constitute < 10% and ketogenic diets (KD), defined as diets with a very high fat content, up to 60–85% (mainly animal fat), 15–30% protein, 5%-10% carbohydrates without the consumption of vegetables (Table I) [1]. There is insufficient scientific evidence to establish a single optimal amount of carbohydrates in the diet of people with diabetes. Current ISPAD guidelines for the nutrition of T1D recommend maintaining a healthy calorie balance, with moderate carbohydrates intake at 45% of daily calories, limiting sucrose up to 10% of total energy, and including a serving of vegetables with each meal [2]. These basic principles of healthy eating for children with diabetes remain the same as for their healthy peers. T1D is a chronic metabolic disease characterized by autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic cells, treated with exogenous insulin injections adjusted to the amount of carbohydrate consumed; however, achieving stable glycemic control remains an ongoing challenge. Historically, carbohydrate restriction, used since the 18th century, was one of the few effective methods of extending the life of people with T1D before the discovery of insulin [3]. Nevertheless, the scientific evidence supporting the effectiveness of this approach in managing T1D is limited. Moreover, these are usually case reports (especially those with adverse effects), surveys or short-term observational studies, which only in some cases seem to confirm a positive effect on reducing the frequency of diabetic complications, while on the other hand there are multi-year, highly documented DCCT/EDIC studies clearly showing that lowering HbA1c reduces the prevalence of these complications [4]. An additional problem facing research in this area is selection bias, as most data come from individuals who have self-decided to follow a carbohydrate-restricted diet rather than from clinical trials. The greatest concerns of physicians about this practice arise from the fact that it may cause ketonemia or ketosis and consequently diabetic ketoacidosis, dyslipidemia, eating disorders, interfere with normal growth in children, increase the risk of hypoglycemia, and impair the effect of glucagon used to treat it and, in general, may be nutritionally inappropriate for the development of children. Another problem is the fact that in anonymous surveys from a multicenter study involving 1,040 young people with T1D, about 40% of parents/legal guardians of children using the LCD diet did not disclose this to their diabetologists, and about 30% admitted that they informed their doctors about the diet but did not receive any understanding or support from them [5]. The main motivators for adapting carbohydrate-restricted diets by patients include postprandial glycemia variability caused mainly by carbohydrates (which is an independent cardiovascular risk factor), and their impact on the average glycemia and the time in range, the inability to match the insulin dose to the increases in glycemia (the more carbohydrates, the more errors and mismatches), greater risk of weight gain due to the high doses of insulin administered. In this narrative review, we aimed to summarize the latest findings on low-carbohydrate diets, the potential consequences of their use, as well as their suggested benefits and impact on glycemic control in children with T1D (Table II).

Table I

Definition of diets based on percentage of carbohydrate in total energy intake and suggested amount of carbohydrate in grams/day, depending on the age of the child [1]

Table II

Potential consequences and suggested benefits of low-carbohydrate diets in children with type 1 diabetes

Concerns about low-carbohydrate diets in children with type 1 diabetes

Dyslipidemia

Carbohydrate restriction requires increasing dietary fat intake in order to maintain caloric demand, which may result in the development of hypercholesterolemia in individuals following LCD, as indicated by a series of case reports and researches [6–9]. This diet-induced dyslipidemia does not correspond to the commonly known pattern of atherogenic dyslipidemia – an increase in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration is accompanied by an increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) concentration, while triglycerides (TG) levels often remain within the normal range [7]. Lipid abnormalities due to LCD can be very serious, particularly in predisposed patients. Güleryüz et al. described a case of a 9-year-old girl, whose LDL-C level was over 800 mg/dL and total cholesterol (TC) level over 1,000 mg/dl after two years of LCD [8]. It is recognized that both T1D and hypercholesterolemia are two independent risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, and their combination further exacerbates this risk [10]. Dyslipidemia may therefore require the initiation of statin treatment, as cases with well response to this therapy have been observed [8, 11].

Ketoacidosis

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a relatively rare complication of diabetes; however, it is potentially life-threatening. It is characterized by metabolic acidosis, ketosis, and a blood glucose level above 250 mg/dl (below in euglycemic DKA) [12]. The prevalence of euglycemic ketoacidosis has increased recently due to the growing popularity of ketogenic diets. A prolonged starvation or diet with a very low carbohydrate intake redirects the body to metabolize stored triglycerides, which results in the formation of ketone bodies, such as acetone, acetoacetic acid and beta-hydroxybutyrate [11]. Although nutritional ketosis is usually insufficient to cause ketoacidosis, it is a condition that requires special caution, and monitoring ketone levels is necessary to prevent it from developing into an acute, severe complication. Patients should be educated about the potential symptoms of DKA, which may include malaise, fatigue, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain. Additionally, they should be aware of other factors exacerbating the risk of DKA, such as infection, inappropriate or insufficient insulin doses, gastroparesis, excessive alcohol consumption, and dehydration.

Hypoglycemia

Carbohydrate restriction and the often concomitant reduction in total caloric intake may lead to a depletion in liver glycogen stores and an increase in the frequency and duration of hypoglycemic episodes. Counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia may also be impaired, particularly at the beginning of LCD [13]. Leow et al. evaluated the effect of VLCD in adults with T1D. Although good glycemic control was achieved, many participants reported more frequent episodes of hypoglycemia [6]. To detect and prevent severe hypoglycemia episodes early, continuous glucose monitoring may be useful. Since a common error in LCD is insufficient calorie intake, a dietetic consultation is recommended to maintain an optimal calorie content in the diet.

Growth disturbances

Insulin is involved in the regulation of the linear growth process directly by stimulating anabolic effects in bone and promoting chondrocytes proliferation and differentiation via insulin receptors, and indirectly through the effect on growth hormone via the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis [14]. In children without T1D, the ketogenic diet resulted in significantly slower growth rates as well as reduced height and BMI [15]. Furthermore, T1D may aggravate growth retardation. Patients with T1D presented reduced serum IGF-1 levels compared to healthy controls, which is associated with growth hormone resistance due to poor glycemic control [16]. Adherence to LCD in patients with T1D may result in more serious growth impairment than in children with epilepsy on a ketogenic diet [15, 17]. The growth retardation may be also related to a higher risk of malnutrition due to the dietary restriction.

Nutritional deficiencies

Another concern with LCD is the risk of nutrient deficiencies. Studies suggest an increased risk of iron deficiency due to a high-fat diet [6]. Another study examined the effect of LCD on micronutrient content and found deficiencies in 6 micronutrients (vitamin B7, vitamin D, vitamin E, chromium, iodine, and molybdenum) [18]. Limited intake of fiber-rich grains and legumes, which are an important source of energy for the microbiome, can lead to dysbiosis and be another cause of B vitamin deficiency [19]. Therefore, in patients with T1D following LCD, it is necessary to monitor vitamin and mineral status, and multivitamin supplementation may be recommended to reduce the risk of above-mentioned deficiencies.

Psychosocial life

Negative consequences of LCD can also affect the psychosocial life of children. The restrictive nature of the diet makes it difficult to follow and involves many sacrifices. When so-called “bad food” is hidden or restricted at home, there is a risk that the child will snack or hoard these products, which can lead to the development of bad eating habits and conflicts with the family [20, 21]. Restrictive meals are not always available in public spaces, which can lead to a social isolation among peers. In addition, the inability to estimate carbohydrates in products that the child is not familiar with causes glycemia fluctuations in the event of their uncontrolled consumption. Moreover, such a restrictive diet increases the risk of developing eating disorders in the future [19].

Potential benefits of low-carbohydrate diets in children with type 1 diabetes

Since the main problem in T1D is the lack of endogenous insulin and thus impaired ability to control blood glucose levels, it seems logical to strive to reduce the intake of carbohydrates due to their greatest impact on increases in glycemia. Recently, LCD have gained enormous popularity in patients with T1D. One of the main reasons may be the very fast noticeable effect in weight loss compared to other weight loss diets considered healthy. The study on 40 youths with T1D, in which participants were randomly assigned to the LCD or to the Mediterranean diet group for six-months, showed significantly greater reduction in body weight and waist circumference at 3 months in the LCD group, however the effects in both groups were comparable after 6 months [25]. The beneficial effect of a carbohydrate-restricted diets on body weight is particularly important today, when more and more children with T1D also struggle with obesity and metabolic syndrome [26]. This can motivate patients to follow the diet and other recommendations, resulting in better metabolic control.

External carbohydrate intake has the greatest impact on blood glucose fluctuations, therefore, a low-carbohydrate diet can stabilize glucose levels, preventing excessive postprandial spikes and subsequent glycemia drops [12]. Studies indicate better improvement in TIR on LCD compared to the Mediterranean diet [25], and a 5% reduction in carbohydrate intake helps achieve the desired time in range above 70% [27]. Another randomized controlled cross-over study of 35 children indicate significantly lower BMI and body weight during the LCD. Moreover, in comparison to a normal healthy diet, adolescents on LCD had higher TIR without episodes of hypoglycemia as well as no disturbances in lipid profile [28]. Maintaining euglycemia for a longer period of time results in lowering HbA1c, while good glycemic control prevents micro- and macrovascular complications [29]. Ozoran et al. reported a case of a 37-year-old patient with late-onset of T1D, who self-implemented a low-carbohydrate diet shortly after the diagnosis. He did not require insulin therapy for the first 18 months, then remained on a minimal dose of long-acting insulin, maintaining good glycemic control and, importantly, no episodes of hypoglycemia or supraphysiological ketonemia were noted [9]. This suggests the possibility of achieving good glycemic control by reducing the need for insulin, which, when administered in large doses, leads to weight gain, increases the risk of obesity and metabolic disease [30, 31]. Avoiding excessive increases and decreases in glycemia reduces the experience of symptoms accompanying these conditions and, consequently, reduces the number of insulin injections and its dose, which reduces the risk of lipodystrophy as well as the costs of treatment and may improve the quality of patients’ life. However in that patient, it was not clear whether adherence to the LCD contributed to the preservation of endogenous pancreatic function or whether maintaining C-peptide may be the reason why carbohydrate reduction was so effective in achieving tight glycemic control in this patient. Moreover, a gradual increase in blood cholesterol levels was observed, which ultimately led to extreme hypercholesterolemia after 6.5 years of follow-up.

As most studies show, limiting carbohydrate intake is associated with a higher risk of hypercholesterolemia [6–9]. However, there are cases where lipid levels did not increase significantly or even decreased [25, 32]. This is presumably related to the degree of carbohydrates restriction and the predominance of unsaturated over saturated fats and trans fatty acids in the diet of these individuals.

Proposed protocol for the management of children with type 1 diabetes on low-carbohydrate diets

An interdisciplinary committee from the Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA, undertook to develop a management protocol for healthcare professionals that outlines the clinical and biochemical follow-up of children with T1D who elect to follow a carbohydrate-restricted diet to ensure medical safety [33]. The scientists also identified key health parameters that required monitoring, such as growth, glycemic control, bone health, cardiometabolic health, and nutritional status.

Once the family expresses a desire to begin a carbohydrate-restricted diet or reports that the patient is consuming less than 100 g of carbohydrates per day, dietary education brochures are provided. Monitoring ketone levels daily in the morning or after the longest fast for 1 week is also recommended. If the blood ketone level is ≤ 1.0 and there are no urine ketones, the child is referred for routine diabetes follow-up at the next visit. If the blood ketone level is >1.0 or urine ketones are present, the medical care provider begins close laboratory and clinical monitoring of the patient according to the protocol (Fig. 1). Routine diabetes follow-ups occur every 3 months, when the physician adjusts insulin doses, reviews insulin dosing strategy, determines whether the carbohydrate-restricted diet meets the family’s expectations for optimal glycemic control, assesses side effects, as well as the child’s height, weight, and puberty status. Laboratory testing is performed at the beginning of the diet, if possible, then every 3 months for the first year, and every 6 months thereafter. Vitamin and mineral supplementation should also be implemented. If at any time the child develops symptoms of ketosis, the healthcare team helps the family reduce ketone levels and provide additional medical assistance if necessary. In addition, if there is any concern based on laboratory evaluation, growth parameters, or blood glucose monitoring (using standard reference ranges for hypoglycemia and time in range), the physician is obliged to issue a strong recommendation to discontinue the low-carbohydrate diet and return to a well-balanced diet. Moreover, if the child has been on a low-carbohydrate diet for more than 2 years, a DEXA scan is recommended.

Case description

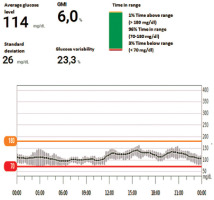

We present the case of a seven-year-old girl with T1D diagnosed in 2022 in our Department of Pediatrics, Endocrinology, and Diabetology with Cardiology Division of the Medical University of Białystok. Since the onset of the disease, she has been treated with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion using a Medtronic 640G pump. In 2023 the pump was replaced with an Omnipod Dash, and a Dexcom continuous glucose monitoring system was applied. Results from March 2025 are presented in Fig. 2. The child uses the ANDROID APS loop – AMA system in the basal version with automatic corrections, without the need to administer meal boluses.

At the time of diagnosis, she consumed daily about 150 g of carbohydrates, and her lipid profile remains normal. Lipid profile 2 years after diagnosis revealed TC 333 mg/dl, LDL-C 258 mg/dl, HDL-C 70 mg/dl, TG 82 mg/dl, both parents without hyperlipidemia. The patient’s mother admitted that she was on a very low-carbohydrate diet (up to 50 g per day). A change in meal composition, nutritional re-education, and administration of meal boluses were recommended. A year later, control lipid profile showed TC 233 mg/dl, LDL-C 170 mg/dl, HDL-C 80 mg/dl, TG 80 mg/dl. The pump was still in the algorithm without meal boluses. Daily insulin requirement was 10 units, including basal insulin in the amount of 8 units (insulin aspart). The patient’s anthropometric development has not deteriorated and remains in the 50th percentile [34] since the onset of the disease – her current weight is 25 kg and height is 120 cm. Her recent HbA1c was 6%. Fortunately, the patient has not experience euglycemic acidosis or episodes of severe hypoglycemia.

Summary

Low-carbohydrate diets are popular, also among patients with T1D, and are usually used with effective metabolic control. However, there is no consensus on the use of LCD in children with T1D and they are not recommended due to the possible side effects. The lack of understanding on the part of the medical team can lead to alienation of these families and poses additional risks. Emphasis should be placed on maintaining a positive relationship between the family and the medical team since supervision of patients using such a nutritional model is necessary, i.e., monitoring ketones and lipid profile, adjusting insulin doses, monitoring the child’s growth and development, supplementation of micronutrients, as well as medical assistance on sick days. If the child or family decides to adapt a carbohydrate-restricted diet, this should be discussed with a dietitian to ensure that the diet is nutritionally complete and to conduct a detailed nutritional assessment with the family, discuss the risks associated with restrictive diets in children and adolescents, including eating disorders, and suggest a range of strategies that the family can use to ensure that their goals are consistent with the medical needs of the child. The LCD diet, designed with the help of a dietitian, can be eucaloric and similar to the Mediterranean diet, ensuring energy requirements while maintaining the glycemic expectations. Open and honest patient-therapeutic team dialogue, considering benefits and risks, monitoring patients are key factors in maximizing glycemic benefits and reducing risk. Nevertheless, multicenter, randomized, multi-year studies are needed to clearly define the modification of carbohydrates in the nutrition of patients with T1D and to resolve the existing controversies.

POLSKI

POLSKI