Introduction

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), due to their relatively low toxicity and unique, tunable optical properties, are promising candidates for many cancer treatment and diagnostic applications, ranging from medical imaging and drug delivery to light-activated therapies [1]. Apart from their distinctive chemical and physical characteristics and their ease of synthesis in various shapes and sizes, low toxicity is a key factor driving the significant interest in AuNPs. Among the various morphologies, gold nanospheres (AuNSs) of different sizes and rod-shaped nanoparticles (AuNRs) of various sizes and aspect ratios (ARs) have been studied the most extensively [2]. Gold in the form of a colloidal suspension of nanoparticles exhibits high biocompatibility due to its high chemical and physical stability. The negative surface charge on AuNPs facilitates the conjugation of various functional groups, ligands, or other biomolecules and chemicals, including drugs, nucleic acids, and antibodies [3, 4].

The localized surface plasmon resonance band (LSPR) of AuNPs is widely recognized for its coherent oscillations of conduction band electrons on the AuNP surface upon light excitation. The wavelength of the LSPR band is determined by the chemical structure, size, shape, and clustering of the AuNPs [5]. Many biological detection and imaging methods utilize the LSPR bands of AuNPs. In particular, AuNRs are excellent candidates as light absorbers, enabling the selective elimination of tumor cells in photodynamic and photothermal therapies [6]. In photodynamic therapy, AuNRs with suitable properties, when taken up by target cells, facilitate the local generation of reactive oxygen species in tissues irradiated with laser light of an appropriate wavelength within the visible or infrared range [7]. In the photothermal approach, abnormal cells are eliminated through a local temperature increase in cells that internalize light-absorbing AuNPs [8–10].

Further research is needed on the metabolism of gold in living organisms. Therapies using this metal require a thorough evaluation of their efficacy. It would also be desirable to develop a form of gold that can be fully meta-bolized. The shape and morphology of AuNPs impact their biodistribution and circulation in the body. To ensure the safe utilization of AuNPs in clinical practice, it is necessary to improve pharmacokinetics and targeting efficacy and to determine delayed toxicity [11].

AuNPs intended for biomedical applications require functionalization to prevent aggregation and deposition while maintaining their plasmonic functionalities. Naked (nonstabilized), uncharged nanoparticles lose their colloidal stability and tend to aggregate. Aggregated nanoparticles not only lose their plasmonic functionalities but also undergo rapid clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), making them susceptible to being trapped in narrow capillary beds and reducing their total circulation time [12]. A frequently used method for stabilizing AuNPs is coating their surface with polyethylene glycol (PEG) [13] PEGylation prevents the adsorption of surface proteins in biological media [14], reduces clearance by the MPS, and prevents cellular uptake [15].

It has been repeatedly shown that, apart from light- activated effects exploited in cancer therapy, AuNPs alone, despite generally high biocompatibility, negatively affect cell viability [16]. Adverse effects on cells were observed for both naked and PEGylated AuNPs [17]. AuNPs induce the production of reactive oxygen species, reduce the potential of the mitochondrial membrane, and, consequently, induce autophagy, apoptosis, or necrosis [18–20]. The cyto-toxicity of AuNPs depends on factors such as concentration, size, shape, surface area, surface charge, capping (stabilizing) agent, and roughness [21]. It is also influenced by the properties of the medium in which the particles are suspended. The presence of serum proteins forming the protein corona alters the physicochemical characteristics of AuNPs and affects the results of in vitro tests [14, 22].

The size and AR of AuNRs are key parameters that determine their optical properties and interactions with cells. Cellular uptake, retention, and distribution within the cell are highly dependent on the size and dimensions of AuNRs [23, 24]. Both theoretical modeling and experimental studies demonstrate that the toxicity of nanoparticles, which is partly dependent on cellular uptake, is related to the size and shape of the AuNPs.

Computational modeling of nanoparticle-membrane interactions shows that AR affects the rate of AuNP internalization [25, 26]. Experimental evidence demonstrates that cylindrical nanoparticles with a high AR are more efficiently captured by cells due to a greater adhesion force between the cell membrane and the nanoparticle surface [27–29]. However, some experimental studies report conflicting results. In a study on the uptake of citric acid-stabilized AuNSs (AR = 1 : 1), Chithrani et al. [24] found that AuNSs (with diameters of 14 and 74 nm ± 10%) were more readily internalized by HeLa cells than AuNRs (14 × 40 and 14 × 74 ± 10%). Other studies have found a non-linear relationship between dimensions and AuNP internalization. For instance, the cellular uptake of non-PEGylated AuNPs by prostate cancer cells (PC-3) is higher for 50-nm AuNSs than for AuNRs in the size range of 30 to 90 nm [30]. There is an optimal particle size for the most efficient membrane wrapping in receptor-mediated endocytosis, one of the mechanisms of AuNP internalization [26, 31, 32].

The relationship between AuNP internalization and to-xicity is also complex. Smaller AuNSs can enter the nucleus, whereas larger ones tend to accumulate in the cytoplasm [33, 34]. Nuclear localization is usually associated with higher toxicity [35]. Studies have shown that non-PEGylated AuNSs exhibit significant toxicity in vivo only within a certain diameter range (8–37 nm) [36]. An inverse correlation between cellular uptake and AR was found for cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-coated AuNRs with a length range of 33 to 55 nm and ARs from 1.1 to 4.0 in MCF-7 cells, although no association of AR with cell viabi-lity was observed. Instead, the observed cytotoxic effect could be attributed to CTAB molecules in the nanoparticle suspension [37].

Kinnear et al. [38] suggested that the effect of AR on cellular uptake may be overestimated. The synthesis of AuNPs of different dimensions requires different chemical environments, resulting in nonidentical chemical composition of the final AuNP suspensions. To ensure consistent chemical compositions of the AuNP suspensions, the team used the thermal reshaping method to obtain different ARs from a single batch of AuNPs. Experiments involving AuNPs functionalized with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and epithelial-derived cells (A549, HeLa), as well as macrophages (J774A.1), have shown that once variables other than AR were eliminated, there was minimal to no effect of AR on AuNP uptake. The analysis of the size- and shape- dependent cytotoxicity of AuNPs is important in the context of their potential applications, mainly because the size of the AuNPs affects their biodistribution in vivo [39]. Because intravenous injection is the typical route of admi-nistration for biomedical AuNPs, understanding the inter-actions between AuNPs and circulating cells of the immune system is essential.

Here, we present the results of the viability evaluation of activated human peripheral blood lymphocytes exposed to PEGylated AuNSs and AuNRs of two different sizes. Activated lymphocytes were chosen as a model of carcinoge-nesis due to their metabolic similarities with proliferating cancer cells [40]. Lymphocyte viability was assessed after activation with phytohemagglutinin (PHA-L), a potent mito-gen that binds nonspecifically to T-cell receptors and stimulates cytokine production and secretion, expression of surface molecules, and cell proliferation.

Material and methods

Chemicals

Tetrachloroauric acid (HAuCl4•H2O) (with a purity of 99.99%) was purchased from Alfa Aesar (USA), and so-dium citrate (HOC(COONa)(CH2COONa)2•2H2O) (≥ 99.00%), CTAB (99.00%), sodium borohydride (NaBH4) (98.00%), silver nitrate (AgNO3) (99.99%), ascorbic acid (AA) (99.00%), O-(2-mercaptoethyl)-O'-methylpolyethylene glycol (PEG-SH Mw ≈ 2000) (99.99%), and saline solution were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA).

Chemical synthesis of AuNPs

All chemicals were dissolved in ultrapure Milli-Q water (18.2 MΩ•cm, 71.98 ± 0.01 mN•m−1) in glass flasks treated with aqua regia before use. Gold nanospheres (AuNSs) were obtained in one-step bottom-up in situ reactions, using HAuCl4 as the precursor and sodium citrate as the reducer [41, 42]. Sodium citrate was used to reduce the aqueous HAuCl4 solution. Sodium citrate cannot reduce HAuCl4 to metallic gold when the reaction solution is cold; the reaction takes place only when heated. For this purpose, 17.623 ml of a 1% HAuCl4 aqueous solution was dissolved in 500 ml of Milli-Q water. The solution was then placed on a heating plate and brought to a boil with stirring (temperature on the heat plate approx. 170°C). Next, 596.6 mg of sodium citrate was dispersed in 51.762 ml of water and rapidly added with vigorous stirring. The solution should change color from clear to yellow to dark red (Fig. 1). After adding sodium citrate, the solution was stirred and heated (approx. 170°C) for 45 min. Once the heat was removed, the solution continued to be stirred while cooling to room temperature. The reaction mixture then took on the characteristic color of AuNSs. Subsequently, the solution was filtered through syringe filters (22 µm) [41, 43, 44]. Gold nanorods (AuNRs) were obtained in two-step bottom-up in situ reactions using seed-mediated growth methods described by Nikoobakht et al. [43] with modifications [44, 45]. Gold seeds (seed solution) were prepared in the first step by dissolving CTAB surfactant (5 ml, 0.2 M) in deionized water, adding the HAuCl4 precursor (5 ml, 0.0005 M), stirring for 10 min, and then adding the cooled reducing agent NaBH4 (0.6 ml, 0.01 M) and vigorously stirring the mixture for 1.5 h. All reagents were added very quickly (one shot). NaBH4 must be freshly prepared and added before bubbling appears, so we used water that had been frozen in an ice freezer in advance. The color of the mixture changed from yellow to brownish yellow. The seed solution was maintained at 28°C to prevent crystallization of the CTAB surfactant. The second step in the synthesis was the growth of gold seeds in solution (growth of nanorods in solution). Seed solution (12 µl) was added to the growth solution containing CTAB (5 ml, 0.2 M), HAuCl4 (5 ml, 0.001 M), AgNO3 (0.075 ml and 0.25 ml, 0.004 M), and ascorbic acid (0.07 ml, 0.078 M). The seed solution was added at a temperature of 27 to 30°C to allow the growth of the AuNRs. After adding the reducing agent to CTAB, the solution was stirred until it became a clear orange color.

PEG functionalization of AuNPs

The capping of AuNSs by PEG-SH (Mw ≈ 2000) followed the previously described protocol [46–48]. This process prevents aggregate formation and enhances nanoparticle stability. In brief, a small amount of previously sonicated PEG-SH (30 min at 40°C) was added to the nanoparticle solution. The solution was stirred for 24 h to facilitate the exchange of citrate ligands with PEG-SH. Excess PEG-SH was removed by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for approx. 30 min (twice). PEGylated nanoparticle fractions were then suspended in a saline solution and stored at 4°C.

The size and location of the AuNRs’ LSPR were controlled by varying the amount of AgNO3. Excess reactants were removed by double centrifugation (6000 rpm for 30 min). The PEG-SH coating was prepared using a modified method as described previously [49, 50]. An aqueous PEG-SH solution was sonicated for 30 min at 40°C and added to the vigorously stirred AuNP solution. The mixture was stirred for 24 h at room temperature to ensure complete ligand exchange with PEG-SH. The minimal amount of PEG-SH required to stabilize the surface of AuNRs was determined according to Manson et al. [51]. Unbound PEG-SH particles were then removed by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 30 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the nanoparticles in the pellet were dispersed in Milli-Q water. After the second centrifugation, AuNRs were suspended in a saline solution.

Physicochemical characterization of AuNPs

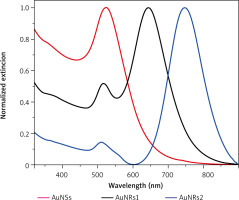

The absorption spectra were obtained using a Varian Cary 4000 spectrometer. All measurements were perform-ed at room temperature (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Normalized extinction spectra of spherical gold nanospheres (AuNSs, red) and gold nanorods (AuNRs) with varying concentra tions of AgNO3 in the growth solution: 0.075 ml (AuNRs1, black) and 0.25 ml (AuNRs2, blue)

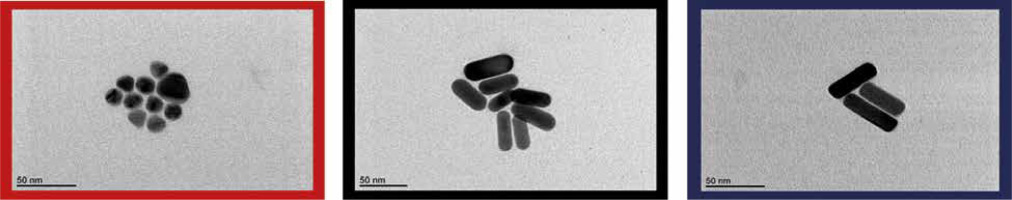

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were taken with a JEOL 1400 microscope operating at 120 kV. AuNSs and AuNRs were drop-casted onto Cu grids and placed on a vacuum desiccator overnight (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

TEM images of spherical gold nanospheres (AuNSs) and gold nanorods (AuNRs1 and AuNRs2). Colors correspond to those in Figure 2 (red, black, and blue, respectively)

The electrokinetic potentials and size distributions of the AuNPs were measured using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS Dynamic Light Scattering Analyzer (Malvern Instruments Ltd.).

Isolation and culture of human lymphocytes

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from buffy coat samples obtained at the local Blood Donation and Blood Treatment Center in Poznan, sourced from healthy volunteers, 8 males aged 29–49 years, who provided individual informed consent. The sodium citrate anticoagulated samples were diluted 1 : 6 in PBS containing heparin (3 mM). PBMCs were then isolated via density gradient centrifugation, using a lymphocyte separation medium (Sigma-Aldrich, C-44010), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the cell suspension was carefully loaded on top of the separation medium, and then samples were centrifuged at 440 × g for 40 minutes at room temperature. The interphase of mononuclear cells was collected and washed twice with culture me-dium. Next, the cell pellet was resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Biowest L0500) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin solution and seeded onto a 96-well plate (2 × 105 cells/well).

Lymphocyte proliferation was stimulated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA-L; 2.5 µg/ml, MP Biomedicals, 151886). Cells were cultured for 72 h at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2.

Evaluation of nanoparticle cytotoxicity

The PEGylated AuNSs had an average particle diameter of 15 nm, whereas the AuNRs were of two different sizes: AuNRs1: 20 × 40 nm and AuNRs2: 22 × 50 nm. All AuNPs were suspended in a physiological saline solution.

Working suspensions of PEGylated AuNPs were prepared from a 0.2 mg/ml stock to produce the desired final concentrations. One hundred microliters of AuNP suspension were added to the cultured lymphocytes at concentrations of 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 µg/ml. Each experiment used a vehicle control with pure physiological saline solution. Every sample was run in triplicate. The cells were incubated with the nanoparticles for 24 h. For the study design diagram see the supplementary figure.

Viability assessment

Cell viability was assessed using a 3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. In this method, metabolically active cells reduce MTT to an insoluble purple formazan via mitochondrial reductases. After solubilization, the formazan concentration was measured spectrophotometrically. The absorbance value was then used as an indicator of cellular viability [52, 53].

After the 24-h incubation with AuNPs, the cells were washed twice in RPMI 1640 without phenol red. Subsequently, MTT reagent (VWR Chemicals 0793, 1.2 mM) was added, and the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Following incubation, the formazan product was solubilized in DMSO, and the absorbance at 540 nm was measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (Epoch, BioTek Instruments, USA).

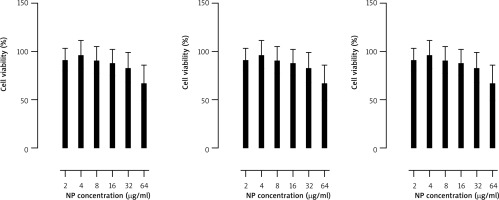

To correct for the absorbance originating from AuNPs remaining in the sample wells despite washing, cell-free samples of AuNP suspensions at concentrations matching those used in the experiment were prepared and processed in the same manner as the experimental samples (washing, centrifugation, and incubations). The absorbance values of the AuNP samples at equivalent concentrations were then subtracted from the absorbance readings of the experimental samples (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Viability assessment of lymphocytes exposed for 24 h to different concentrations of AuNPs of three kinds: AuNSs (left); 15 nm, AuNRs1 (middle); 20 × 40 nm, AuNRs2 (right); 22 × 50 nm. Cell viability was evaluated using an MTT assay. n = 8, mean ± SD in three independent experiments. Numbers indicate pvalues of the t-test for samples significantly different than the control (p < 0.05)

Cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the control, calculated using the following equation:

Statistical analysis

The mean, standard deviation, median, and minimum and maximum values were calculated for all variables. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Statistical analysis was conducted using nonparametric methods because the assumptions for parametric tests were not met.

Changes in the viability of cells exposed to nanoparticles at increasing concentrations were assessed using Friedman’s test. Samples exposed to different types of AuNPs at the same concentration were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Post-hoc Dunn’s test was applied in both cases to identify differing groups. Spearman’s rank correlations were also used to explore possible relationships between nanoparticle concentration and cell viability.

For all calculations, a p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were performed using Statistica software (version 13, TIBCO Software Inc., 2016).

Results

Synthesis and characterization of AuNPs

AuNSs and AuNRs were characterized using UV/vis spectroscopy and TEM (Fig. 3). The location of UV/vis bands provides information about the average particle size, whereas their full width at half maximum can be used to determine the dispersion of particles in a colloidal solution. The UV/vis extinction spectrum of AuNSs showed a characteristic single peak at 520 nm, whereas AuNRs exhibited both longitudinal and transverse LSPRs (Fig. 2). Spectroscopic studies in the UV/vis spectral range showed that the reso-nance maximum was approx. 520 nm in the transverse direction and, in the longitudinal direction, could be tuned from the visible to the near-infrared range, depending on the presence of AgNO3 in the growth solution (the maximum was at 640 nm or 745 nm). The final concentration of AuNPs was calculated according to Fernández-López et al. [46]. The functionalization of AuNPs improves their stability in various solvents. PEG-SH was chosen not only for its biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity but also for its particularly strong affinity for AuNPs, facilitating binding by forming a gold-thiolate bond. All PEGylated AuNPs were prepared in three concentrations: 20, 100, and 200 µg/ml and then transferred to a saline solution (similar to human body fluids with 0.9% NaCl). The hydrodynamic diameter of the AuNSs was measured by dynamic light scattering. The size distribution of the AuNSs was 45 nm and 58 nm before and after functionalization, respectively. The zeta potentials of AuNSs changed from –12.1 mV to –21.3 mV after PEG functionalization. Naked AuNRs showed cationic surfaces 11.7 mV and 12.7 mV for AuNRs1 and AuNRs2, respectively. After functionalization the zeta potentials were reduced to negative levels (–16.0 mV – AuNRs1 and –18.7 mV – AuNRs2).

Cytotoxicity of AuNPs

In our experiments, AuNPs of all three sizes/shapes negatively affected the viability of activated human lymphocytes in a dose-dependent manner, with the highest concentration (64 µg/ml) causing the most significant decrease (Fig. 4). For AuNSs and AuNRs1, a significant decrease in viability was observed at concentrations of 32 and 64 µg/ml. Statistical analysis showed that the difference in effect between concentrations of 32 and 64 µg/ml was significant (p < 0.05) only for AuNSs. For AuNRs2, the effect of AuNPs at 8 µg/ml was significantly weaker than at 16 µg/ml (p < 0.05), 32 µg/ml, and 64 µg/ml (p < 0.001). The concentration of 16 µg/ml had a significantly weaker effect than 64 µg/ml (p < 0.01).

AuNRs2 decreased lymphocyte viability significantly more strongly than AuNRs1 at concentrations of 8, 16, and 32 µg/ml. At concentrations of 16, 32, and 64 µg/ml, AuNRs2 had a significantly stronger effect on lymphocyte viability than AuNSs. AuNRs1 affected lymphocyte viability significantly more strongly than AuNSs but only at a concentration of 64 µg/ml.

Overall, larger AuNRs (approx. 22 × 50 nm) were more toxic than smaller 20 × 40 nm AuNRs and 15 nm AuNSs, but the observed differences in the AuNP-induced reduction in lymphocyte viability were significant only at high concentrations.

Discussion

The literature describes the influence of various media on the stability of AuNPs (water, phosphate-buffered saline, phosphate-buffered saline containing bovine serum albumin, and dichloromethane) [51]. PEGylated AuNSs were also shown to be stable at salt concentrations ranging from 0.15 to 1 M [51], whereas citrate-capped AuNPs aggregated immediately. The PEG coating greatly improved the suspension stability in all tested media. Due to the NaCl, PEG-functionalized AuNSs showed lower stability after redispersion in phosphate-buffered saline and phosphate-buffered saline/bovine serum albumin, compared to dichloromethane and water [51]. Stiufiuc et al. [54] reported a fast and efficient one-step synthesis of AuNSs coated with unmodified PEG of various molecular weights and surface charges. The ligand exchange reaction is often used as a highly versatile tool to functionalize Au-NPs for specific applications. Removing surface-bound CTAB with more biocompatible surface ligands is required for biological applications of AuNPs. CTAB is cytotoxic; hence, PEG-SH is one of the most important ligands used for this purpose, because it confers superior biocompatibility and colloidal protection of PEG-S protected AuNPs. However, it was difficult to produce high-yield ligand exchange products that effectively remove CTAB. During the ligand exchange reaction, the Au-S bond was created, and unbonded PEG was removed through centrifugation.

The results confirmed that the surface-enhanced Raman scattering signal is unaffected by the length of the PEG molecular chain enclosing the nanoparticle and that the stability is not affected by the addition of a strong salt solution (0.1 M NaCl), indicating its potential use for in vitro and in vivo applications.

Although AuNPs have various applications, particularly in humans, their use must overcome the impact of NaCl and pH. Therefore, Tseng et al. [55] incorporated NaCl into a pulse spark discharge system used for AuNP synthesis to simulate the human body and study its stability. The addition of a long-chain carboxymethylcellulose polymer or polyvinylpyrrolidone k30 (PVP-k30) has been shown to prevent aggregation and precipitation in NaCl or different pH values and maintain dispersion by increasing the repulsive force between particles. A similar observation in AuNRs showed that 1.0 M NaCl did not affect the tensile strength of PEGylated AuNRs, whereas CTAB-stabilized nanoparticles aggregated immediately upon the addition of NaCl [56]. Furthermore, the concentration of PEG and the functionalization process do not affect the optical properties of AuNPs.

The size-dependent cytotoxicity of AuNPs in vitro has been extensively researched, but some studies have produced conflicting results. AuNPs affect not only the viability but also the proliferation of lymphocytes. The apparent contradiction in experimental results is unsurprising because the dimensions and AR of AuNPs are just two among many factors that determine their uptake and toxicity. Parameters such as surface charge and ligand chemistry [31], the presence of residual chemicals, surface capping methods, and protein adsorption on AuNPs also affect the rate of internalization [32]. Both inhibitory and stimulatory effects of AuNPs on mitogen-stimulated lymphocyte proliferation have been reported. Liptrott et al. [57] demonstrated a concentration-dependent stimulatory effect of 8.8 nm AuNPs on PHA-stimulated PBMC proliferation. This effect was partially attenuated when the AuNPs were capped with a ligand shell. Conversely, Devanabanda et al. [58] observed dose-dependent inhibition of mitogen-stimulated (PHA or PWM) proliferation of lymphocytes incubated with 50 nm AuNPsClick or tap here to enter text. Mitogen-stimulated lymphocyte proli-feration is typically assessed via [3H]thymidine incor-poration, which allows monitoring of the rate of DNA synthesis [58]. In assessing cell viability by MTT reduction, viability is inferred from the bulk activity of intracellular oxidoreductases and electron donors that reduce MTT to colored formazans. The result of the MTT reaction depends on both cellular metabolism and the number of cells in the sample [59, 60]. Therefore, in our experiments, to avoid confusing the potential stimulatory or antiproliferative effects of AuNPs with a decline in viability, AuNPs were added to the culture at 72 h after mitogen stimulation. We chose this timing because most lymphocytes are expected to have already entered the G1 stage of the cell cycle, and the effect of the nanoparticles on lymphocyte activation should be minimal [61, 62].

Devanabanda et al. [58] found that AuNPs with an average diameter of 50 nm had no effect on the viability of human and murine lymphocytes after 72 h of incubation at concentrations up to 200 µg/ml. However, the prolife-rative response to mitogens, including PHA, was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner. The AuNPs used in their study were not PEGylated and were synthesized through a chemical reduction method using trisodium citrate. Saqr et al. [63] found that 70-nm non-PEGylated AuNPs synthesized via a reduction method involving plant extracts were cytotoxic to HeLa and normal human primary osteoblasts at concentrations as low as 0.62 µg/ml. Abo-Zeid et al. [64] investigated the cytotoxicity of 50-nm and 30-nm PEGylated AuNRs, 15-nm AuNSs, as well as semicubes in human lymphocytes in the concentration range of 0.05 to 1 µg/ml. They observed an increase in cytotoxicity and inhibition of mitotic activity with decreasing AuNP size. Interestingly, Yu Pan et al. [65], in a study with ultrasmall, spherical, non-PEGylated, phenylphosphine-capped AuNPs, found a size difference as small as 0.2 nm to be relevant in terms of cytotoxicity. In HeLa cells, 1.2-nm AuNPs after 24 h of incubation were found to mainly cause apoptosis, whereas incubation with slightly larger 1.4 nm AuNPs resulted in a much higher percentage of necrotic cells in the annexin V/PI assay. As mentioned above, ultrasmall AuNPs can enter the cell nucleus, whereas larger AuNPs tend to accumulate in the cytoplasm; therefore, the mechanism of their toxicity may be different [33]. Nuclear penetration is associated with higher toxicity [66].

Because of a multitude of conditions potentially affecting the experimental results, it is difficult to draw general conclusions about the effect of AuNPs on cell viability based on the outcomes of individual studies. The apparent discrepancies may result from various factors and experimental parameters, apart from AuNP size and AR, which account for differences in cell viability. These factors and parameters include, but are not limited to, cell type [67], incubation time, method of viability assessment [68], size range, surface charge, modifications [69] and the presence of impurities related to the method of AuNP synthesis [22, 70]. The CTAB surfactant commonly used in AuNR synthesis, if not removed or overcoated, can be responsible for the cytotoxicity of AuNR suspensions [22]. It has been suggested that surface chemistry plays a much larger role in AuNPs’ toxicity than their size and morpho-logy [71, 72]. Viability assessment results also depend on culture conditions, such as serum protein concentration, which affects AuNPs’ cellular uptake [73].

Our analysis revealed the high inter-individual variability in response to AuNP exposure. The cytotoxicity of AuNPs as a function of their size and/or shape has been previously studied in various cell types, including cells of epithelial origin: HEP-2 and canine MDCK [74], U87 and primary human dermal fibroblasts [20, 71, 75], HeLa and HEK293T [76], BEAS-2B cells (transformed human bronchial epithelial cells) [77], MCF-7 and SKBR-3 breast cancer cells, as well as PC-3 prostate cancer cells [69, 78], rat cardiomyocytes [79], HepG2 liver cancer cells and HL-7702 J774 normal liver cells [80], A549 and NCIH441 lung adenocarcinoma cells [70], A1 murine macrophages [81] and B lymphocytes [15]. Most of these studies were based on established continuous cell lines. This approach allows for high replicability; however, it might not accurately reflect individual susceptibility to the toxicity of AuNPs. Immortal, genetically altered cell lines have inherent limitations as a model of in vivo state. Assessment of cell viability using a primary culture of donor-derived cells has the potential to be more reliable in predicting AuNP toxicity, albeit at the expense of reproducibility and statistical power. In our study, we used buffy coat, which is a by-product of blood processing in a blood donation center not normally used for transfusion. This provides a convenient way to obtain a large volume of white blood cells. It also allows multiple tests to be performed on cells obtained from a single donor from a single blood draw, eliminating one potential source of inconsistency.

Le Guével et al. [82] reported that AuNPs at nontoxic concentrations induced changes in lymphocyte subpopulations. Dendritic cells pretreated with 12-nm AuNPs stabilized with glutathione and co-cultured with lymphocytes stimulate the proliferation of Th1 lymphocytes and CD56bright NK cells secreting IFN-Click or tap here to enter text. These results suggest that AuNPs at concentrations below the toxic threshold may indirectly shift the balance in Th subpopulations in favor of Th1 cells. Both T and B lymphocytes can internalize AuNPs through endocytosis; however, PEGylation has been shown to significantly reduce the uptake of AuNPs by B cells [15, 83]. As indicated earlier [84], AuNP studies in the context of their biomedical applications must take into account the potential adverse impact of AuNPs on the normal function of the immune system and how the immune response may change the effectiveness of AuNP-based therapeutic or imaging procedures [19].

Our study was limited by the relatively small number of samples. Additionally, the MTT assay detects mitochondrial reductase activity, which generally correlates well with the number of viable cells in culture. However, the assay does not distinguish between changes in metabolic activity and decreases in cell number due to apoptosis and/or necrosis. Further studies will be needed to determine the mechanisms responsible for the decline in cell viability, and to investigate the ability of AuNPs to induce cell death in proliferating cells. Future studies should include an analysis of cellular uptake and membrane adhesion of AuNPs. One of the challenges of cytotoxicity testing is the insufficient sensitivity of available methods. The MTT assay, which is well established and widely used, may not be sensitive enough to measure the cytotoxic effects of nanoparticles at low concentrations. It is crucial to note that the size-dependent toxicity of AuNPs in vivo is related to their tendency to accumulate in organs and is strongly associated with circulation time [85]. Smaller AuNPs tend to pass through the renal filtration system, whereas larger nanoparticles accumulate in tissues, leading to potentially harmful changes in non-target sites of the body [86]. The distribution of AuNPs across organs and tissues adds another layer of complexity that is not addressed in this in vitro study and will require a different experimental approach.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that high concentrations of AuNPs have a detrimental impact on lymphocyte viability in vitro. Specifically, the 22 × 50 nm AuNRs exhibit greater toxicity compared to the 20 × 40 nm AuNRs and 15 nm AuNSs. Thus, when determining a safe dosage of AuNPs for therapeutic or diagnostic purposes, it is crucial to consider not only the concentration but also the shape and size of the nanoparticles. In the context of designing targeted photodynamic and photothermal cancer therapies, it is essential to recognize the light-independent, non-selective cytotoxic effects of AuNPs on both tumor and normal cells. Therefore, current and future in vivo applications of AuNPs necessitate a careful evaluation of the benefits and risks associated with exposing living cells to nanomaterials. Achieving the right balance involves selecting the optimal size and surface modifications to minimize adverse effects while retaining the desired properties of AuNPs.