Introduction

Thymic epithelial tumours (TET) are a rare and heterogeneous group of malignancies originating from the epithelial cells of the thymus [1]. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) classification, TET encompass a wide histopathological spectrum ranging from indolent type A and AB thymomas to more aggressive B1, B2, and B3 subtypes and thymic carcinomas [2]. Thymic epithelial tumour samples are frequently preserved through formalin fixation and paraffin embedding (FFPE) due to their long-term stability and compatibility with histological evaluation. However, the fixation and embedding process introduces significant challenges for molecular analysis [3]. Formalin induces crosslinking of nucleic acids with proteins and creates chemical modifications that can degrade DNA and interfere with enzymatic reactions. Additionally, prolonged storage in pathology archives can significantly induce DNA fragmentation and degradation [4, 5].

Recent advances in molecular biology highlight the importance of genomic alterations in the development and progression of human diseases, including TET. Molecular techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), Sanger sequencing, and next-generation sequencing, are increasingly utilised in screening and diagnosing TET [6, 7]. The efficacy of these methods heavily relies on obtaining high quality and quantity DNA, a task complicated by the chemical modifications induced during FFPE processing. The selection of an adequate extraction procedure is critical, particularly when dealing with long-term preserved and limited material [8]. This study conducts a performance analysis of 3 commercial DNA extraction kits: the QIAamp, GeneJET, and MasterPure kits, across 20 FFPE and 3 fresh TET samples. By comparing the yield, purity, and amplifiability of DNA from each extraction method, we aim to identify the most effective strategy for recovering DNA from FFPE TET, thereby ensuring the reliability of the molecular analyses and clinical diagnostics for TET.

Material and methods

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded material and pathological examination

The 23 TET samples used in this study were obtained from the pathology archives of Military Hospital 103. All patients provided consent for the use of their samples in this research study. Twenty FFPE samples were stored 7–9 years at –20oC (Table 1). Three samples were freshly collected through surgical resection and stored in RNAlater® solution at –20oC. Haematoxylin and eosin stain and immunohistochemical staining using specific monoclonal antibodies (CD34, p53, and EMA) were also conducted to assess the quality of all TET samples. The morphology of the TET samples was pathologically diagnosed by 2 independent pathologists based on the WHO classification [2]. All samples showed strong staining signals and maintained their structural integrity, making them suitable for subsequent molecular analysis.

Table 1

Sample quality control report of fresh (TF) and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (TFP) thymic epithelial to samples

DNA extraction methods

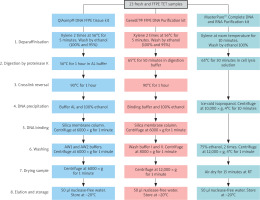

DNA extraction from TET samples was carried out by the QIAamp® DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, USA), the GeneJET FFPE DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA), and the MasterPure Complete DNA and RNA Purification Kit (LGC Biosearch Technologies, USA), following the manufacturers’ instructions (Figure 1). In this manuscript, these kits are shortly referred to as “QIAamp”, “GeneJET”, and “MasterPure” kits, respectively.

Assessment of quality, quantity, and amplifiability of DNA

The DNA yield and integrity were evaluated using a NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) [9] and a Qubit 3 fluorometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) [10].

DNA samples were used for PCR amplification of 3 genes, TP53 (F: 5’-CAGGTCTCCCCAAGGCGCAC-3’; R: 5’-GCAAGCAGAGGCTGGGGCAC-3’; ENSG00000141510), GTF2I (F: 5’-AA GCCAAAGGTCCGGTGAC-3’; R: 5’-ACATAGAACCTAGTGGTGA ATGAAT-3’; ENSG00000263001), and NOTCH1 (F: 5’-TGCACACTATTCTGCCCCAG-3’; R: 5’-ACTTGAAGGCCTCCGGAATG-3’; ENSG00000148400), which are highly associated with the development of TET [11, 12].

The obtained PCR products were used for Sanger sequencing using the BigDyeTM Terminator v3.1 kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). Sequences were evaluated with FinchTV V1.4 software (RRID: SCR_005584) using reference sequences from the EMBL database. DNA samples from TET were then subjected to a quality control test for whole genome sequencing (WES) at Macrogen Inc. (South Korea).

Results

Assessment of the yield and purity of DNA

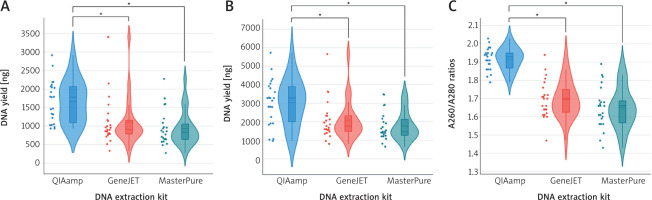

A comparison of three commercial extraction kits was conducted using 23 fresh and FFPE TET samples (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Comparison of DNA yield and purity across thymic epithelial tumor samples. The violin plots illustrate DNA yield measured by the Qubit (A) and NanoDrop (B) methods, as well as the A260/A280 ratios (C)

The coloured dots represent all data points. The asterisk symbol denotes statistical significance (p-value < 0.05). Solid and dashed middle lines within the boxplot indicate median and mean values, respectively. The upper and lower ends of the boxplot correspond to the third and the first quartile.

Both Qubit and NanoDrop techniques showed that the QIAamp kit produced the highest DNA yield among the methods tested (Figure 2). The Qubit and NanoDrop analyses returned median DNA yields of 1785.5 ng (58.33 ng/µl) and 3280 ng (114.51 ng/µl), respectively. The variation in DNA yields obtained from Qubit and NanoDrop measurements comes from their unique quantification methodologies and sensitivities [10]. Qubit employs fluorescent dyes to measure double-strand DNA in a sample, enabling precise and specific quantification of intact DNA molecules. In contrast, NanoDrop measures DNA using UV absorbance at 260 nm, resulting in the nonspecific assessment of all nucleic acid species and other impurities. This method may result in the DNA concentration being overestimated 2–4-fold relative to Qubit, especially in samples containing degraded nucleic acids [9, 10]. GeneJET and MasterPure produced decent DNA yields, but MasterPure had the lowest yields among the extraction methods (Figure 2). The GeneJET kit produced DNA amounts of 902.1 ng (Qubit) and 1771.5 ng (NanoDrop), while the MasterPure kit yielded 838.9 ng (Qubit) and 1460 ng (NanoDrop). The DNA variables obtained from QIAamp compared to GeneJET and MasterPure were statistically significant, demonstrating QIAamp’s superior efficiency in recovering DNA from both fresh and FFPE samples.

In regard to purity, DNA extracted using QIAamp showed the highest and most consistent purity values, with A260/A280 ratios remaining in the optimal range of 1.8–2.0 [9]. GeneJET and MasterPure exhibited lower median purity and greater variability, with many samples below the minimum purity threshold of 1.8, suggesting significant protein contamination in the TET samples evaluated [9]. The reduced purity can affect subsequent applications requiring high-quality DNA, such as Sanger sequencing and WES sequencing [5, 13, 14].

Assessment of the integrity and amplifiability of the DNA extracted from thymic epithelial samples

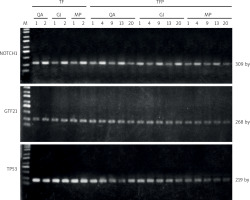

Gel electrophoresis showed successful amplification of NOTCH1, GTF2I, and TP53 genes from all DNA extracted using the 3 different commercial kits. Fresh samples yielded clear bands for all target genes at the expected sizes across the 3 extraction kits, indicating high-quality DNA for PCR analysis (Figure 3). The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples included TFP1, 4, 9, 13, and 20, encompassing both sexes and a diverse age range of 22–68 years. They had been preserved for a maximum duration of 9 years and represent various TET histological subtypes. Figure 3 reveals that all 3 kits yielded distinct single bands, confirming successful DNA recovery from FFPE tissues. However, GeneJET and MasterPure kits exhibited more faint bands for NOTCH1 and TP53 products, particularly in samples from aggressive B2 (TFP13) and B3 (TFP20) subtypes [2]. The DNA extraction efficiency is compromised due to the increased DNA degradation and reduced recovery capabilities of the extraction kits [4, 5]. The varied patient demographics and TET subtypes show that the 3 kits tested can consistently provide adequate DNA in both quantity and quality for PCR analysis of archival FFPE tissues.

Figure 3

Agarose gel electrophoresis of NOTCH1, GTF2I, and TP53 polymerase chain reaction products amplified from DNA extracted from thymic epithelial to samples by the QIAamp (QA), GeneJET (GJ), and MasterPure (MP) kits

M: Biosharp® 1 kb plus DNA ladder; TF1-2: fresh samples; TFP1, 4, 9, 13, and 20: formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples.

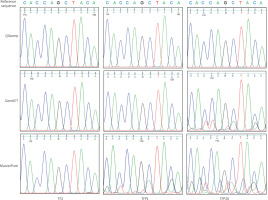

After PCR analysis, products amplified for NOTCH1 were then subjected to Sanger sequencing to assess the reliability of DNA extracted from a fresh TF1 (subtype B3) and 2 FFPE TET samples (TFP1 – subtype A and TFP20 – subtype B3) using 3 commercial extraction kits (Figure 4). The sequencing chromatograms obtained from QIAamp- and GeneJET-extracted DNA display sharp, well-defined peaks with minimal background interference, and the base cells matched precisely with the reference NOTCH1 sequence. The Phred quality scores consistently exceed the minimum threshold of 20, highlighting the effective recovery and suitability of obtained DNA samples for subsequent applications across both fresh and FFPE tissues [15, 16].

Figure 4

Chromatogram depicting the Sanger sequencing results of the NOTCH1 sequence derived from polymerase chain reaction products of fresh (TF2) and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded thymic epithelial to (TFP1 and TFP20) tissue samples

Reference sequence for NOTCH1 was sourced from the EMBL database. Q-scores are represented by a grey bar on each read. The dashed blue line represents the minimum Phred score of 20, which is considered acceptable for accuracy.

DNA extracted with the MasterPure kit exhibited low signal clarity and strong background noise (Figure 4). This indicates that DNA samples may degrade and become contaminated, leading to inconsistent Sanger sequencing results. Fluctuations in peak heights and overlapping signals can reduce the signal-to-noise ratio, obscure genuine heterozygous peaks, and result in false positive outcomes [16, 17]. The findings indicate that the DNA extraction has a critical impact on the quality of Sanger sequencing as well as other sequencing techniques, particularly in the case of difficult FFPE samples. The TFP20 (subtype B3) demonstrated poorer sequencing quality compared to TFP1 (subtype A), indicating that more aggressive subtypes pose additional difficulties in extraction due to their cellular characteristics, such as compact epithelial cells, dense fibrous stroma, necrosis, and incomplete reversal of formalin-induced crosslinks [18].

Our findings are further supported by the quality control report for WES sequencing of TET samples (Table 1). The results of the quantification indicated that all samples achieved satisfactory DNA yields, varying 0.97– 4.58 µg, with integrity numbers exceeding the minimum threshold of 7.0 required for library construction and sequencing [19]. These parameters attained a “Pass” quality control result, confirming the effective preparation of the WES library and subsequent performance of sequencing.

Discussion

The FFPE tissue samples stored in hospital pathology archives serve as valuable sources for disease research at the molecular level. The integrity and quality of DNA, therefore, are crucial to the successful execution of molecular analyses [8, 13]. Failure to obtain high-quality DNA could compromise the molecular techniques, resulting in incorrect interpretations and reduced reproducibility [19]. Therefore, choosing a reliable DNA extraction kit is an essential task.

This study systematically compared the performance of three commercial DNA extraction kits, QIAamp, GeneJET, and MasterPure, using both fresh and FFPE TET samples. Our findings consistently demonstrate that the QIAamp kit provides superior DNA yield, purity, and integrity, supporting its suitability for downstream molecular applications. The superior performance of QIAamp likely arises from its optimized silica-membrane chemistry and its protocol, which effectively removes crosslinked proteins and fixative residues in old FFPE samples [8, 19]. Although GeneJET and MasterPure produced amplifiable DNA, their lower purity and weaker PCR signals indicate limited suitability for old or aggressive FFPE samples. In particular, the dense epithelial architecture and fibrosis characteristic of high-grade TET subtypes may further hinder DNA recovery and exacerbate fragmentation [18]. Our results are consistent with previous studies, which have shown that QIAamp-based protocols frequently yield longer DNA fragments, better variant calling, and coverage indicators from FFPE samples in comparison to the Maxwell™ RSC DNA FFPE Kit from Promega [19]. Watanabe et al. also reported that DNA extracted from FFPE samples aged up to 12 years using the QIAamp kit generated consistent results in both yield and purity [5].

Building upon the assessment of DNA yield and purity, the functional quality of the extracted DNA through Sanger sequencing was evaluated to verify its performance in downstream analyses. High-quality chromatograms from QIAamp- and GeneJET-derived DNA confirmed their compatibility with Sanger sequencing and WES analyses. Conversely, the noisy and overlapping signals from MasterPure-extracted DNA, particularly for old and aggressive type B3 sample, suggest contamination or degradation, which can obscure true genetic variants and compromise downstream analyses [16, 17]. The findings are consistent with previous investigations indicating that QIAamp reliably yields high-quality DNA from FFPE tumor tissues across various cancer types, such as colon, liver, and melanoma [8, 19].

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that the QIAamp kit stands as the superior choice for obtaining high-quality DNA from TET samples across a diverse range of patient demographics and storage durations. The kit consistently produced high-quality DNA, facilitating dependable PCR, Sanger sequencing, and WES sequencing. The GeneJET kit was effective for PCR and Sanger sequencing; however, it proved less suitable for WES sequencing due to the poor DNA quality and quantity derived from the aggressively and long-term preserved FFPE TET samples. The MasterPure kit is solely adequate for PCR analysis.