Introduction

A goiter is defined as an enlargement of the thyroid gland, typically resulting in a size exceeding twice its normal dimensions or a weight surpassing 40 grams (Figure 1). It is estimated that approximately 5% of the global population is affected by goiter [1]. Among these cases, a specific subtype known as a substernal or diving intrathoracic goiter occurs when more than 50% of the thyroid gland descends into the mediastinum. The reported incidence of diving goiters varies widely in the literature, ranging from 5% to 15.7% across different studies [2–10]. There are alternative criteria for defining a diving goiter. One common definition, based on chest computed tomography (CT), describes it as the extension of the thyroid gland more than 3 cm beyond the thoracic inlet with the patient’s neck in hyperextension, or when the gland extends below the fourth thoracic vertebra [11, 12].

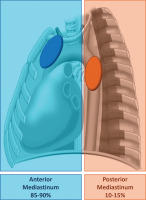

Figure 1

A goiter (arrow) is defined as an enlargement of the thyroid gland, typically resulting in a doubling of its size or an increase in weight beyond 40 g

Epidemiology and distribution

Substernal goiters occur more frequently in women than in men, with a female-to-male ratio of approximately 1.6 : 1. The average age of diagnosis tends to be in the sixth decade of life. In terms of anatomical distribution, the majority of these goiters (85–90%) descend into the anterior mediastinum, while a smaller proportion (10–15%) extend into the posterior mediastinum (Figure 2) [1–4].

Clinical significance

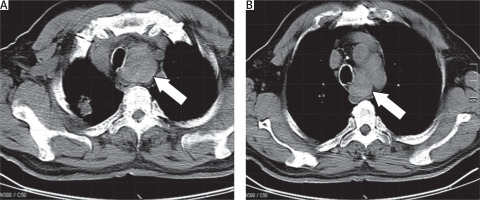

Retrosternal or diving goiters are clinically significant due to their potential to compress mediastinal structures such as the trachea, esophagus, and blood vessels, leading to respiratory distress, dysphagia, or superior vena cava syndrome in severe cases (Figure 3). Surgical intervention is often required when symptoms develop, particularly when airway compromise is a concern [2–6].

Methods

This review was based on a comprehensive analysis of peer-reviewed literature addressing the preoperative evaluation and surgical management of retrosternal diving intrathoracic goiters. Key sources were identified from the PubMed, Scopus and Cochrane databases, focusing on articles from 1946 to 2024, using search terms such as retrosternal goiter, substernal goiter, diving goiter, intrathoracic thyroid, sternotomy, and sternotomy. Clinical and radiological characteristics influencing the need for thoracic surgical approaches were extracted from the studies, with emphasis on predictive factors for sternotomy or lateral thoracotomy. Literature sources used provided data on incidence, surgical techniques, and outcomes associated with diving goiters.

Discussion

Overview of substernal goiters and complications

Substernal goiters develop gradually as the cervical thyroid gland extends into the mediastinum, a process that typically spans more than 5 years. Despite the slow progression, these goiters can lead to significant complications, even in patients who are asymptomatic. The gradual increase in size may result in tracheal compression (Figure 3), which is a critical concern as it can impair breathing and contribute to tracheomalacia – a condition in which the tracheal walls become weak and prone to collapse. While tracheomalacia in substernal goiters is relatively rare, it can result in severe respiratory compromise during surgery and may necessitate tracheostomy to secure the airway [3, 13].

In addition to tracheal compression, large substernal goiters may cause vascular compression and dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) due to their proximity to the esophagus and great vessels in the chest. In extreme cases, substernal goiters can lead to sudden and catastrophic outcomes, including respiratory distress and even sudden death if not properly managed. Furthermore, the risk of malignancy within substernal goiters is not insignificant, ranging from 3% to 21%. Given these risks, surgery remains the only definitive and effective treatment, even for asymptomatic patients [1–4, 13].

However, thyroidectomy for substernal goiters is not without risks. One of the most common postoperative complications, especially following bilateral thyroid surgery, is hypoparathyroidism. This occurs when the blood supply to the parathyroid glands is disrupted during the ligation of thyroid vessels, leading to transient hypocalcemia in many cases. While temporary hypocalcemia is common, permanent hypocalcemia has been reported in 1–3% of patients. Preserving the parathyroid glands during large thyroid surgery can be particularly challenging, given the size of the goiter and the complexity of the procedure. Careful identification of the parathyroid glands and meticulous dissection near the thyroid tissue can reduce the risk of accidental removal or damage. In cases where the parathyroid glands are damaged, autotransplantation into nearby muscle tissue should be considered to preserve their function [13].

Preoperative evaluation and surgical approach

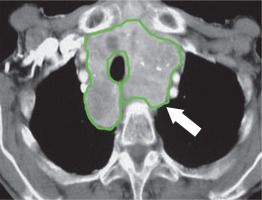

Accurate preoperative evaluation is crucial for determining the optimal surgical approach in patients with substernal or diving goiters. The primary diagnostic tool for this evaluation is chest CT, which is widely recognized as the gold standard in assessing the extent and characteristics of substernal and intrathoracic goiters. CT imaging provides detailed information about the size, shape, and anatomical position of the goiter, as well as its relationship with surrounding mediastinal structures, including the trachea, esophagus, and great vessels. This detailed anatomical mapping is essential in predicting whether a more invasive surgical approach, such as sternotomy or lateral thoracotomy, will be required for safe and complete removal of the thyroid gland [14].

For the majority of thyroidectomies, a cervical approach is sufficient, even in cases of substernal goiters. However, approximately 2–5% of patients with diving goiters require a more extensive approach that goes beyond the cervical region, including sternotomy [15]. The reported need for sternotomy varies from 1 to 11% of cases, largely depending on the size and extent of the goiter’s mediastinal extension [16].

The anatomical location of the goiter plays a critical role in guiding the choice of surgical approach. A cervical incision is typically appropriate when the thyroid gland is located above the aortic arch, at the level of the T4 thoracic vertebra. In contrast, when the goiter extends below the right atrium, a full sternotomy is usually required to provide adequate exposure for safe excision. For goiters descending between the aortic arch and the pericardium, a partial sternotomy or a sternal split may offer sufficient surgical access while minimizing the invasiveness of the procedure [17]. In these instances, the decision is made based on the extent of the goiter and its proximity to critical structures, balancing the need for complete removal with minimizing surgical risks (Table I).

Table I

Surgical access of diving goiter according to anatomical location

CT imaging not only guides the surgical approach but also helps surgeons anticipate potential complications by identifying critical anatomical relationships. For example, when the goiter exerts pressure on mediastinal structures such as the trachea or great vessels, preoperative imaging allows for a tailored surgical plan that reduces the likelihood of intraoperative and postoperative complications [14–17].

Recent studies and sternotomy predictors

Several recent studies have provided valuable insights into the management of diving goiters and the factors predicting the need for more invasive surgical approaches, such as sternotomy.

A study by Oukessou et al. analyzed the outcomes of 116 patients with substernal goiters, treated between 2014 and 2020 using a cervical approach. Of these patients, 84.48% had goiters extending into the anterior mediastinum and 15.52% into the posterior mediastinum. Notably, none of the patients required sternotomy, and the cervical approach was successful in all cases. Postoperative complications included transient vocal cord paralysis in 2.58% of patients, permanent paralysis in 1.72%, transient hypocalcemia in 8.62%, and permanent hypocalcemia in 1.72%. The authors concluded that the cervical approach is both safe and effective, with low morbidity and no reported mortality [18].

A recent meta-analysis of 69 studies examined the prevalence of extracervical approaches (ECA), such as sternotomy or thoracotomy, in the excision of substernal goiters. The study used three common definitions, with Definition 1 (goiters descending below the thoracic inlet) being the most widely used. This definition included 3,441 patients from 31 studies, and the pooled prevalence of ECA was 6.12%. Definitions 2 and 3 included 2,957 and 2,921 patients, respectively, but specific prevalence rates for ECA were not detailed for these groups. The results indicate that approximately 6% of patients with substernal goiters require an extracervical approach, underscoring the importance of patient counseling regarding the potential risks and morbidity associated with these procedures, even though they are relatively rare [19].

In another study, Linhares et al. conducted a retrospective review of 109 patients with substernal goiters to identify preoperative factors associated with the need for transthoracic surgical excision. Of these patients, 11 (10%) underwent partial sternotomy, and 6 (5.5%) required total sternotomy. Logistic regression analysis revealed that goiters extending beyond the sternal notch into the mediastinum were significantly associated with the need for sternotomy. A mediastinal extension of ≥ 5 cm beyond the sternal notch was particularly predictive of the need for sternotomy, with a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 86.5%. The study concluded that, while most substernal goiters can be managed with a transcervical approach, those with deeper mediastinal extension (≥ 5 cm) are more likely to require a sternotomy [20].

A comprehensive review by Gordon McKenzie and William Rook in 2014 assessed whether specific clinical and radiological features could reliably predict the need for sternotomy in thyroidectomy for retrosternal goiters. Their analysis of studies from Medline (1946–2014) and Embase (1974–2014) identified several key predictors. Clinical risk factors included a goiter history exceeding 160 months and increased thyroid tissue density, the latter of which increases the risk of sternotomy by 47-fold. CT findings of posterior mediastinal or subcarinal extension were also significant predictors. In addition, features such as ectopic nodules, dumbbell-shaped goiters, and thoracic components wider than the thoracic inlet were associated with a higher likelihood of requiring sternotomy. In some cases, minimal upper sternotomy may suffice, particularly when the goiter extends only to the aortic root. Importantly, patients with bilateral multinodular goiters and intrathoracic extension face a higher risk of complications, such as recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, which should be discussed with patients during the informed consent process [21]. A summary of the most relevant clinical features associated with the need for sternotomy is presented in Table II.

Table II

Clinical features associated with increased complexity of surgical management in diving goiter. These characteristics suggest a need for thoracic surgical assistance due to the potential difficulty in accessing and removing the goiter through a cervical approach alone

Radiological predictors and surgical planning

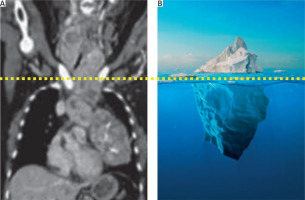

From a radiological perspective, several key features help predict the need for sternotomy in the management of substernal goiters. Goiters extending below the aortic arch or into the posterior mediastinum, as well as those with a bell-shaped appearance, are strongly associated with the requirement for more invasive surgical approaches. Additionally, if the width of the goiter exceeds the thoracic inlet, this serves as another significant predictor of the need for sternotomy. These radiological features demonstrate a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 75%, making them reliable indicators for planning surgical intervention. Other notable radiological markers include the presence of primary intrathoracic goiters (thyroid tissue originating entirely within the chest cavity) and cases where the goiter appears to lack clear boundaries on imaging, which may suggest malignancy or fibrosis (Table III). Additional indications for sternotomy include recurrent goiter cases, particularly when scarring from previous surgery complicates a cervical approach. Goiters forming an “iceberg phenomenon”, where the mediastinal mass is larger than the thoracic inlet, are also likely to require sternotomy. Large goiters, typically exceeding 15 cm in diameter or 162 cmł in volume, are more likely to necessitate a more invasive surgical approach, as are cases involving malignancy, a long disease history (over 13.5 years), significant tracheal compression, or deep extension into the posterior mediastinum [22–25] (Figure 4).

Table III

Radiological features from chest CT and other imaging modalities that suggest a need for thoracic surgery in the management of diving goiters. These features predict difficulties in cervical access and are strong indicators for considering sternotomy or thoracotomy

Figure 4

Sternotomy is indicated when the mediastinal mass has a diameter exceeding that of the thoracic inlet. The image shows a characteristic “iceberg” appearance, where the majority of the goiter is hidden beneath the sternum

Akinci et al. conducted an analysis of the CT findings of 41 patients who underwent thyroidectomy for substernal goiter. Their study revealed that patients requiring sternotomy had significantly larger total thyroid volumes, retrosternal thyroid volumes, craniocaudal lengths, and anterior-posterior dimensions compared to those treated with a cervical approach. Furthermore, while most patients in the cervical group exhibited grade 1 mediastinal extension, the majority of those in the sternotomy group presented with grade 2 extension. The study concluded that these CT findings, particularly total thyroid volume and mediastinal extension, are valuable predictors for determining the need for sternotomy [22].

Sormaz et al. investigated the relationship between the volume and craniocaudal length of the mediastinal portion of the thyroid gland and the requirement for an extra-cervical approach in retrosternal goiter surgery. Their study, which included 47 patients, found that 8 (17%) required an extra-cervical approach. Patients in the extra-cervical group had significantly larger craniocaudal lengths (77 mm) and mediastinal volumes (264 cm3) compared to those managed with a cervical incision (31 mm and 40 cm3, respectively). The study identified cut-off values of ≥ 66 mm for craniocaudal length and ≥ 162 cm3 for mediastinal volume, with high sensitivity and negative predictive values of 100%. These findings suggest that a thyroid volume of ≥ 162 cm3 extending below the thoracic inlet is a key predictor of the need for an extra-cervical approach, while smaller volumes strongly favor the feasibility of a cervical approach [23]. Further research with larger patient populations is recommended to validate these results.

In a study conducted by Riffat et al., 97 cases of retrosternal goiter surgery were reviewed to assess the radiological factors predictive of sternotomy. Of the 97 cases, 17 required sternotomy, while 80 were managed with cervical excisions. The CT analysis showed that significant predictors for sternotomy included posterior mediastinal extension, extension below the carina, and a conical-shaped goiter where the thoracic inlet becomes constricted. The study concluded that CT imaging is a useful tool for predicting the need for sternotomy, allowing for better preoperative planning and coordination between surgical teams [24].

Casella et al. also aimed to identify preoperative risk factors for sternotomy in the management of mediastinal goiters. Their analysis of 98 patients treated between 1995 and 2008 found that 12 (12.2%) required a sternotomy. Logistic regression analysis highlighted significant risk factors for sternotomy, including goiter extension below the aortic arch, posterior mediastinal involvement with subaortic extension, and a long history of mediastinal goiter (> 160 months). The study concluded that sternotomy can be predicted effectively in certain cases, and performing it when necessary minimizes surgical complications [25].

Surgical techniques and alternatives

Pata et al. compared the use of sternal-split versus cervicotomy for the removal of mediastinal goiters, finding that the sternal-split provided adequate access to both anterior and posterior mediastinal goiters without requiring full sternotomy. While hospitalization was slightly longer for sternal-split cases, complication rates were similar between the two approaches, and no serious complications occurred [26]. While sternotomy may seem like a more invasive approach, it offers several advantages. A median sternotomy or lateral thoracotomy provides a wider operative field, minimizes the risk of catastrophic bleeding, and ensures the complete removal of potentially malignant tissue, along with any affected lymph nodes. These approaches may be particularly beneficial when malignancy is suspected or when the goiter extends into deeper mediastinal structures [27].

Emerging minimally invasive techniques

Since the first report of endoscopic thyroidectomy by Hüscher in 1997, there has been ongoing debate about whether endoscopic thyroidectomy qualifies as minimally invasive surgery. Over time, various techniques have emerged, with the transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach (TOETVA) becoming a popular choice for managing thyroid diseases [28]. Among endoscopic approaches, TOETVA is the only scar-free method, making it highly appealing to patients for cosmetic reasons.

Despite these advantages, TOETVA presents several technical challenges. Maintaining the surgical workspace can be difficult, especially with CO2 insufflation, which is necessary to create adequate space for the procedure. This can lead to potentially serious complications such as CO2 embolism, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and subcutaneous emphysema. To reduce these risks, the development of gasless TOETVA has offered an alternative with improved safety. However, gasless TOETVA introduces new challenges, such as smoke accumulation due to limited gas circulation and instrument interference from multiple concentrated incisions [29, 30].

Several innovations have been proposed to overcome these technical barriers in gasless TOETVA. These include the use of customized trocars, a novel suspension system to maintain the surgical field without CO2, and flexible suction placement to resolve the issue of smoke accumulation. These advancements have significantly improved both the safety and effectiveness of gasless TOETVA, making it a more practical option for patients [30].

In comparison, a newer technique, the endoscopic thyroidectomy via sternocleidomastoid muscle posteroinferior approach (ETSPIA), has also shown promise as a minimally invasive alternative to TOETVA. A study comparing 50 patients undergoing ETSPIA with 50 patients undergoing TOETVA found that ETSPIA had several advantages, including shorter operation time (243.40 vs. 278.08 minutes), less intraoperative blood loss (20.60 vs. 33.00 ml), and a shorter length of stay (6.82 vs. 8.26 days). Furthermore, ETSPIA resulted in better protection of the parathyroid glands, as evidenced by smaller postoperative changes in parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels compared to TOETVA. Although ETSPIA had more central lymph node dissections, the number of positive lymph nodes was not significantly different between the groups. Overall, ETSPIA was associated with faster recovery, reduced trauma, and better parathyroid preservation [28].

Moreover, the first reported case of simultaneous removal of a primary substernal goiter and parathyroid adenoma using gasless TOETVA demonstrated its feasibility for treating small tumors without any postoperative complications. This milestone case illustrates the expanding role of gasless TOETVA in thyroid and parathyroid surgery, providing a viable, minimally invasive option for selected patients [31].

In conclusion, while TOETVA remains an innovative and scar-free option for endoscopic thyroidectomy, newer approaches such as ETSPIA are proving to be valuable alternatives, offering shorter operative times, reduced trauma, and enhanced recovery. As these techniques evolve, the choice between them should be individualized based on the patient’s specific anatomical and clinical considerations.

Non-surgical alternatives and emerging therapies

Approximately 20–40% of diving goiters are asymptomatic and are often discovered incidentally during routine radiological screenings or imaging conducted for unrelated reasons [32]. Despite the lack of symptoms, these goiters can still pose significant risks, which must be carefully considered, particularly in high-risk surgical patients. In selected cases where surgery may not be the optimal approach, radioiodine therapy has been shown to reduce the thyroid gland volume by approximately 30% [33]. However, while this non-surgical option can be effective in shrinking the gland, it is important to note that papillary carcinoma – a common form of thyroid cancer – has been diagnosed in approximately 19% of patients with asymptomatic diving goiters, with a reported range of 3–21% [34].

A recent study by Wang et al. evaluated the long-term efficacy and safety of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for intrathoracic goiter in 22 patients over a median follow-up of 12 months. The results demonstrated a significant reduction in goiter volume, with a volume reduction rate (VRR) of 64.6%, and patients who underwent multiple RFA sessions experienced greater volume reduction compared to those with single sessions. The study emphasizes the importance of using CT/MRI, in addition to ultrasonography, for accurate pre- and post-RFA assessments. This confirms that RFA is a viable treatment option for nonsurgical candidates, offering a minimally invasive alternative in specific cases [35]. These findings underline the necessity for a comprehensive evaluation to determine the most appropriate treatment approach.

Multidisciplinary approach

Managing substernal goiters requires a multidisciplinary team, including general surgeons, otolaryngologists, thoracic surgeons, and anesthesiologists. A collaborative approach ensures safe and effective outcomes, especially in complex cases involving deep mediastinal extension. Successful management relies on careful preoperative planning, coordination between specialties, and adherence to the principles of surgical excellence and patient safety [1, 4, 6].

Future perspectives

Looking ahead, advances in imaging and minimally invasive techniques may further refine the management of substernal goiters. Gasless transoral endoscopic techniques and robot-assisted procedures hold promise in reducing the invasiveness of goiter excision. Continued research into preoperative risk stratification, alongside innovations in non-surgical therapies such as radiofrequency ablation, may broaden treatment options, particularly for high-risk or nonsurgical candidates. As surgical technologies evolve, the goal remains to improve patient outcomes while minimizing risks and postoperative complications.

Limitations

This study is limited by its reliance on previously published literature, which may vary in terms of study design, sample size, and quality of evidence. The heterogeneity of the included studies, particularly regarding definitions and classifications of retrosternal goiters, may affect the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the retrospective nature of many of the studies analyzed introduces potential biases, such as selection bias and incomplete data reporting. The review also lacks prospective, randomized clinical trials that could offer higher levels of evidence to definitively guide the surgical management of diving goiters. Additionally, variations in imaging techniques and surgical approaches across institutions could influence the outcomes reported, limiting the consistency of the conclusions drawn.

Conclusions

Diving goiters, although often asymptomatic, can pose significant clinical challenges due to their potential to compress vital mediastinal structures and their association with malignancy, particularly papillary carcinoma. While radioiodine therapy offers a non-surgical option for reducing gland volume in select cases, surgical removal remains the definitive treatment for symptomatic or complex goiters. Preoperative imaging, particularly chest CT, plays a critical role in determining the appropriate surgical approach, with sternotomy being necessary in a small percentage of cases based on anatomical and radiological features. The use of a sternal-split technique has emerged as a viable alternative to full sternotomy, offering adequate access to the mediastinum with comparable outcomes and minimal complications. Successful management of diving goiters requires meticulous planning, advanced surgical skill, and a multidisciplinary approach to ensure patient safety and optimal outcomes. By adhering to these principles, even the most complex cases can be managed effectively, with a commitment to minimizing harm and ensuring patient well-being.