Introduction

Worldwide, drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is one of the most common drug side effects and significant causes of acute hepatitis and acute liver failure (ALF) [1]. The scale of the problem in Poland is unknown, due to low reporting of adverse drug reactions by healthcare workers, patients and the entities responsible for the drug to the global WHO database (VigiBase) via the European Medicines Agency – EudraVigilance [2]. Currently, more than 1,100 substances with potential hepatotoxic effects are known. Conventional drugs remain the most common cause of DILI in Europe and North America. Amoxicillin-clavulanate is in first place on this list. It is followed by antituberculosis drugs (isoniazid, pyrazinamide, rifampicin), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (diclofenac, ibuprofen), immunosuppressants (azathioprine, infliximab) and other antibiotics (nitrofurantoin, minocycline, azithromycin, levofloxacin) [3-5]. Drug-induced ALF is most frequently caused by acetaminophen (paracetamol) overdose in the West (e.g., Sweden, the UK), South America, and Australia. In Spain and Germany, other drugs, such as antibiotics or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, appear to be more common causes of ALF [6].

DILI classification

Most DILIs are idiosyncratic. They occur in only a small number of exposed individuals (1 in 1000 to 1 in a million), so detection during a clinical trial is extremely difficult, and it usually occurs after the drug is marketed. They are unpredictable, largely dose-independent, and symptoms may appear after a long latency period [7, 8]. Some cases of DILI are due to direct reaction, which is predictable, dose-dependent and occurs in nearly all exposed individuals if a threshold dose or duration is exceeded. Symptoms appear quickly, within hours or days after exposure, and their severity depends on the drug dose taken. Proper dose selection can prevent their development [7, 8]. The third, recently described, mechanism of DILI has been defined as indirect. It arises when the biological action of a drug affects the host immune system, leading to a secondary form of liver injury. Like idiosyncratic DILI, indirect reactions are generally independent of the dose of drug administered and have a latency of weeks to months with varying clinical manifestations [7-9]. Table 1 presents the DILI classification.

Table 1

Diagnosis

Liver biochemical tests

DILI is largely a clinical diagnosis of exclusion, relying on a detailed medical history including medication exposure (start and stop date of the suspected drug, dose changes – if any and when, previous use of the medication, whether the drug was re-dosed), physical examination, the pattern and course of liver biochemistry tests before and after drug discontinuation, and exclusion of other causes of liver disease. Most cases of DILI occur in the first 6 months of taking a new medication, although the latency period from start of intake to onset of liver injury can vary from days to months and even years. A long latency period is typical of nitrofurantoin and methotrexate. The following parameters are used in everyday clinical practice to assess liver injury: the activity of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and serum concentration of total and direct bilirubin. Serum albumin concentration and international normalized ratio (INR) are markers of the DILI severity. Clinically significant DILI is commonly defined as any one of the following: (A) serum AST or ALT > 5× upper limit of normal reference value (ULN) or ALP > 2× ULN (or pretreatment baseline if baseline is abnormal) on two separate occasions at least 24 h apart; (B) total serum bilirubin > 2.5 mg/dl along with elevated serum AST, ALT, or ALP activity; or (C) INR > 1.5 with elevated serum AST, ALT, or ALP activity [3, 8].

The biochemical pattern of DILI is based on increased activity of aminotransferases and ALP, and in general it can be categorized as primarily hepatocellular (serum ALT, AST activity at least 5× ULN or R ratio above 5), cholestatic (ALP activity at least twice the ULN or R ratio less than 2), or mixed (R ratio between 2 and 5). The R ratio is defined as serum ALT/ULN divided by serum ALP/ULN [10, 11]. The pattern of liver injury should be assessed by the first biochemical tests performed after the event. They can change as the condition progresses. The biochemical characterization of DILI may be helpful in managing patients’ therapy, including the decision about hospitalization. Only in the case of mild DILI can treatment be performed in an outpatient setting. In other cases, the patient should be referred to hospital, especially if biochemical parameters increase in the control tests and clinical symptoms occur (jaundice, ascites, encephalopathy, coagulopathy, injury of other organs). The classification of DILI severity is presented in Table 2 [11]. The activity of liver enzymes should decrease rapidly after termination of the suspected drug therapy. Improvement of liver injury after drug discontinuation is important in DILI diagnosis. Resolution of injury after discontinuation helps confirm the causal relationship with the drug. Biochemical improvement occurs faster in hepatocellular than in cholestatic type of liver damage. The time to decrease of liver enzymes activity may be longer in drugs with a long half-life. Certain drugs have their own specific pattern of liver injury, such as hepatocellular with isoniazid, nitrofurantoin, and disulfiram; cholestatic with anabolics; and a mixed pattern with amoxicillin-clavulanate and amiodarone.

Table 2

DILI severity classification according to International DILI Expert Working Group [11]

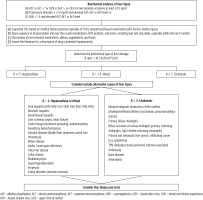

Other laboratory test, including serologic, molecular and liver imaging, are used in differential diagnosis. The proposed diagnostic algorithm for DILI is shown in Figure 1.

Liver imaging

Liver ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging

The results of liver imaging in DILI are usually normal; nevertheless, all patients with suspected DILI should undergo some type of liver imaging. Typically, it starts with abdominal ultrasound (US) to exclude presence of cirrhosis, biliary obstruction, or focal liver changes. The choice of additional imaging depends on the clinical context, i.e. symptoms and biochemical type of liver injury. In patients with cholestatic liver damage, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) should be considered despite normal ultrasound results to evaluate for pancreatic and biliary tract disease (stones, cancer, primary sclerosing cholangitis – PSC) or to confirm drug-induced biliary changes. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis caused by drugs – similar to PSC – has been described after the use of 5-fluordeoxyuridine in hepatic artery infusions for the treatment of cancer metastasis to the liver, metamizole, docetaxel, and in ketamine abusers [12-15].

Liver elastography

Elastography is an uncommonly performed examination in individuals with suspected DILI. So far, only a few studies investigating the use of elastography in DILI have been published. It is an effective and simple tool for monitoring liver injury in patients with psoriasis treated with methotrexate (MTX). This drug causes liver fibrosis and cirrhosis through a direct reaction mechanism. The risk of their development is increased by nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), prevalence of which is higher among patients with psoriasis than in the general population. Studies conducted in Italy, the Netherlands, the United States and India have shown that NAFLD affects 45.2% to 47% of patients with psoriasis [16-19].

Similar studies have been conducted in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treated with MTX. In contrast to psoriasis, in these patients, liver stiffness assessed by real-time shear wave elastography (SWE) and the cumulative MTX dose were not correlated. Substantial liver fibrosis on SWE was observed in about 5% of MTX-treated patients with RA and was associated with only a high body mass index, suggesting that other comorbidities might have a more important role in liver fibrosis [20].

Japanese researchers presented evidence for the usefulness of elastography in assessing liver injury after oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin combination (FOLFOX) treatment used in advanced colon cancer. They observed a clear change in stiffness of the liver after chemotherapy within 48 hours, and the stiffness was normalized in most cases after 2 weeks. In one of the 5 evaluated patients, stiffness did not return to normal and the patient showed biochemical features of liver damage [21]. Oxaliplatin rarely causes a transient increase in serum aminotransferase activity, but it is often associated with sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS) and nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH) with portal hypertension that does not cause cirrhosis [22]. It appears to be too early to recommend elastography for monitoring drug hepatotoxicity.

Liver biopsy

A liver biopsy is not a routine tool use in every case of suspected DILI but it can be helpful in excluding other causes of liver disease. Certain medications are associated with specific histological patterns of liver injury that can be confirmed by biopsy (e.g., autoimmune-like hepatitis, vanishing bile duct syndrome – VBDS, or SOS). On the other hand, histological features may be inconclusive, especially when a single drug causes several different changes. An analysis conducted within the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN), a nationwide registry of DILI in the United States, covering over 2,000 patients, showed that liver biopsy was performed statistically significantly more often when the time between taking a potentially hepatotoxic drug and the onset of liver injury symptoms was longer, on average 2 months, or when more severe liver damage was observed. Ultimately, there was no difference in determining causality between this group of patients and those in whom biopsy was not performed. From the same registry, 50 individuals who had undergone liver biopsies within 60 days of symptom onset were selected. A 5-point scale (DILI probable: 1, 2, 3, DILI unlikely: 4, 5) was used before and after biopsy to assess for causality. Histology review changed the causality score in 34 cases (68%), with an increase in DILI likelihood in 24 (48%) and a decrease in 10 (20%). However, only in 8 cases (16%) did the biopsy change the causality score clinically significantly, i.e. from probable to unlikely DILI [23].

Liver biopsy may be considered in the following cases:

in selected patients with suspected DILI, when the histological features may confirm this diagnosis or provide an alternative diagnosis,

to differentiate drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis (DIAIH) from idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis (AIH),

when the liver biochemistries or symptoms do not improve after drug withdrawal [8, 24].

Clinical diagnoses of AIH and DIAIH are challenging since both conditions have heterogeneous disease manifestations clinically as well as histopathologically. Histological features observed in AIH and previously considered as typical and pathognomonic for it include:

lymphocytic/lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates in portal tracts extending into the lobule beyond the limiting plate into the adjacent lobule with damage and progressive loss of hepatocytes at the portal-lobular interface (interface hepatitis),

presence of an intact lymphocyte within cytoplasm of a hepatocyte (emperipolesis),

hepatocyte rosette formation (a small group of hepatocytes arranged around a small, sometimes centrally visible lumen), are also found in 89%, 34% and 40% of DIAIH cases, respectively [25, 26].

In DIAIH, the presence of portal neutrophil infiltrates and cholestasis is more frequently demonstrated. Confirmation of fibrosis may also be helpful in distinguishing AIH from DIAIH [27].

The spectrum of histological features observed in idiosyncratic DILI is very wide. Table 3 presents the histological phenotypes of DILI. Liver biopsy may assess the severity of the disease and prognosis. A higher degree of necrosis, fibrosis, microvesicular steatosis, and bile duct loss is associated with a worse prognosis, whereas eosinophils and granulomas are more often found in those with a milder degree of DILI [24].

Table 3

Histological phenotypes of DILI [7]

[i] ACE inhibitors – angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, DI-AIH – drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis, DILI – drug-induced liver injury, GCS – glucocorticoids, HMG-CoA – 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, ICI – immune checkpoint inhibitor, NRH – nodular regenerative hyperplasia, NRTI – nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor, NSAIDs – nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, OCPs – oral contraceptive pills, OPV – obliterative portal venopathy, SOS – sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, TNF – tumor necrosis factor

Genetic testing

A missense variant (rs2476601) in the PTPN22 gene, located on chromosome 1, encoding the substitution of tryptophan for arginine in cytoplasmic tyrosine phosphatase, is a genetic risk factor for multiple drugs and across major ethnic groups with an OR of 1.4. The strongest association was demonstrated for DILI induced by amoxicillin-clavulanate in Europeans (OR = 1.62, 95% CI: 1.32-1.98, alleles frequency: 13.3%). Several genetic studies have also identified distinct human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles as risk factors for specific drugs. Among Europeans carrying the HLA A*02:01 and DRB1*15:01 alleles, the rs2476601 variant doubles the risk of DILI induced by amoxicillin-clavulanate [28]. Other HLA alleles have also been found to be specific for certain drugs. For example, HLA-B*57:01 is associated with flucloxacillin, HLA-B*35:02 with minocycline, and HLA-A*33:01 with terbinafine. In general, the identified HLA alleles have low positive predictive value, because of the low incidence of DILI in the general population, but a high negative predictive value. Therefore, pretreatment HLA testing will likely not prove useful in most circumstances to prevent DILI, but HLA testing may be helpful in DILI diagnosis and causality assessment [29-32].

Models of causality assessment

Several clinical tools have been developed for DILI causality assessment. The assessment of causality is made based on laboratory and clinical features following exposure and exclusion of other causes of liver injury. A summary causality score is generated that typically ranges from definite (highly probable) to excluded (unlikely).

The oldest available tool is the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM), also known as the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences scale, introduced in 1993 and modified in 2016. The score ranges from –9 to +14 points, with the same five likelihood categories [10, 33, 34].

The Maria-Victorino Clinical Diagnostic Scale (CDS) uses similar variables to the RUCAM but excludes concomitant medications and includes points for extrahepatic manifestations. The CDS is not used widely in clinical practice because it was shown to be inferior to the RUCAM [35, 36].

The Digestive Disease Week-Japan 2004 score (DDW-J) is a modification of the RUCAM with the inclusion of drug-lymphocyte stimulation test (DLST) results and peripheral eosinophilia. Scores range from −5 to +17 points. Although the DDW-J was shown to be superior to the original RUCAM in Japanese patients, it is not currently used outside of Japan because of the lack of widely available and reproducible DLST assays [37, 38].

The latest Revised Electronic Causality Assessment Method (RECAM) is currently available online. This semiautomated, computerized platform was developed on the basis of the RUCAM scale and additionally uses data from US and Spanish DILI registries, literature data, and the LiverTox database. This scale is at least as effective as RUCAM in diagnosing DILI, but better than the prototype in extreme diagnostic cases. It has been tested only in the United States and Spain and has not been used in patients with liver damage caused by herbs and dietary supplements [39].

Management of DILI

The prompt identification and discontinuation of the offending drug is crucial in early DILI management. An attempt to continue therapy may be considered only in mild idiosyncratic DILI in patients without liver comorbidities and carefully monitored for disease progression. In these cases, the ALT level should not exceed 5× ULN in hepatocellular damage, or 2× ULN in cholestatic injury, and serum bilirubin concentration should remain normal. Transient and self-limited aminotransferase elevations are encountered with drugs such as isoniazid and statins that can resolve with continued dosing, presumably because of metabolic and/or immunological adaptation [7]. Patients with severe acute liver injury need to be closely monitored for disease progression, and those with ALF (coagulopathy and encephalopathy) should be urgently referred to a liver transplant center because of their low likelihood (~25% chance) of spontaneous recovery [8]. General supportive care is recommended for all patients with acute DILI, including the use of antiemetics, analgesics, antipruritics, and parenteral hydration, as needed.

The list of specific antidotes is unfortunately very short. Cholestyramine is used to treat persistent cholestasis caused by terbinafine or leflunomide (a disease-modifying drug used in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis). Cholestyramine is used at a dose of 4 g every 6-8 hours for 2 weeks [40]. L-carnitine improves survival in children with acute liver injury presenting with valproic acid-induced hyperammonemia. An initial dose of 100 mg/kg should be given intravenously within 30 minutes, with subsequent doses of 15 mg/kg every 8 hours until clinical improvement is achieved [41]. In management of severe SOS following hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT), defibrotide (a complex mixture of single-stranded polydeoxyribonucleotides derived from porcine intestine that has antithrombotic and profibrinolytic activity) is used at a dose of 6.25 mg/kg administered every 6 hours (25 mg/kg per day) for the shortest period of 21 days, up to a maximum of 60 days [42]. However, it has not been shown to be superior to the best maintenance treatment for SOS prophylaxis after HSCT [43].

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is the most commonly used antidote in patients with acute paracetamol poisoning. The first dose of 150 mg/kg after dissolving in 5% glucose (volume for adults: minimum 200 ml, recommended 500 ml; for children < 20 kg – 3 ml/kg; and > 20 kg – 100 ml) should be given over 15-60 min intravenously, followed by 50 mg/kg over the next 4 hours (12.5 mg/kg/h) then the third dose of 100 mg/kg over 16 hours thereafter (6.25 mg/kg/h). It is recommended to administer the second and third doses by infusion pump or drip infusion. The total dose of NAC is 300 mg/kg over 24 hours. In patients with liver injury, treatment is extended until ALT is decreasing and INR is below 2. The recommended maintenance dose is 6.25 mg/kg. Intravenous administration is preferred in pregnant women, in cases of intolerance to the oral form of NAC or ileus. Oral dosing: 140 mg/kg load followed by 70 mg/kg every 4 h [8]. A 3-day course of NAC should be considered in adult patients with DILI-related ALF in light of improved 3-week outcomes, particularly in patients with early-stage encephalopathy [44]. Outcomes with a short course of parenteral NAC were poorer in children with non-APAP ALF, limiting enthusiasm for its use in children [45].

Methylprednisolone at a dose of 1 mg/kg is frequently given to patients with severe immune-mediated hypersensitivity reactions, including the drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) [46]. In some instances, a short course of corticosteroids (i.e., 1-3 months) with rapid tapering may be of benefit in patients with autoimmune features (DIAIH) on biopsy as well as for patients with DILI caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors or tyrosine kinase inhibitors [47].

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) may improve symptoms of pruritus and hasten DILI recovery, but large, randomized controlled trials are needed to determine the optimal dose and duration. Currently, UDCA is recommended at a dose of 10-15 mg/kg [8, 48].

Liver transplantation is often the only therapeutic option in patients with acute liver failure.

Conclusions

Idiosyncratic DILI is a rare but life-threatening side effect of drugs. There is evidence showing that patients with pre-existing liver disease, especially cirrhosis, are at increased risk of a severe course of liver disease. The risk/benefit ratio should be assessed in these patients before starting potentially hepatotoxic treatment. Despite ongoing research, there are still no diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers for DILI.