In cases of myocardial infarction (MI) complicated with cardiogenic shock (CS), the use of circulatory support devices, such as venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO), and left ventricle assist devices, such as Impella – or a combination of them, termed ECMella – prior to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has demonstrated the potential to enhance patient outcomes [1, 2]. However, it presents challenges, as some studies report an elevated incidence of complications in patients receiving ECMella support. Such interventions may facilitate myocardial recovery or serve as a bridge to heart transplantation or durable left ventricle assist device (LVAD) and biventricular assist device (BiVAD) [3].

A 57-year-old man called Emergency Medical Services due to severe gastrointestinal symptoms accompanied by diarrhea. While awaiting the arrival of the ambulance, the patient experienced a CS due to extensive anterior myocardial infarction, resulting in an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). The patient was defibrillated three times unsuccessfully. Upon arrival at the nearest hospital, he was connected to VA-ECMO, which restored spontaneous rhythm and revealed a newly diagnosed left bundle branch block.

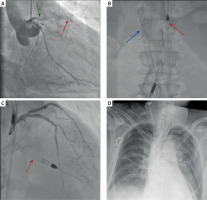

The patient was transported to our facility and underwent coronary angiography, which revealed multivessel coronary disease (MVD) with occlusion of the left anterior descending artery (LAD), circumflex artery (Cx), and right coronary artery (RCA) (Figure 1 A).

Figure 1

A – Total occlusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery from the ostium (green arrow), showing a visible stent (red arrow) from a previous percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). B – Implantation of the Impella CP (red arrow). The ECMO cannula is visible (blue arrow). C – Coronary angiography following PCI of the left coronary artery (LCA) with Impella CP (red arrow). D – Radiographic image of the new heart, captured on the first day after heart transplantation

The patient was deemed suitable for primary PCI and required Impella CP support due to severe LV dilation while presenting with CS despite ECMO and escalated doses of vasopressors. The Impella was inserted via right femoral access after paving the way to the left ventricle with balloon angioplasty of the right external iliac artery (Figure 1 B). Under intravascular ultrasound guidance, the PCI of the eft main artery (LM), left anterior descending artery (LAD), left circumflex artery (LCx), and marginal branch (Mg) was performed. Three drug-eluting stents were implanted, with optimal results (Figure 1 C).

The Impella CP was sustained for the next 7 days, until hemolysis signs appeared. After a period of improvement and stabilization, the patient’s condition deteriorated, leading to qualification for a heart transplant, which was performed 23 days after OHCA (Figure 1 D).

The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit, where comprehensive, recommendation-based intensive treatment with hemodynamic monitoring and intensive rehabilitation was implemented. Due to prolonged mechanical ventilation, a tracheostomy was performed. Further hospitalization was also complicated by pneumonia.

Despite the implementation of intensive treatment strategies, no long-term significant clinical improvement was observed, leading to multiorgan failure exacerbated by multiple infection-related complications. That culminated in the patient’s death following a 3-month hospitalization.

CS represents a considerable challenge within the healthcare system, particularly for post-MI patients who have experienced cardiac arrest. Emergency care systems strive to enhance the application of ECMO treatment in 10 min when we cannot achieve ROSC after 10 min of RKO (20 min from CA in hospital and under 60 min in OHCA). However, this strategy remains challenging to implement due to several factors, including extended ambulance response times and the transport of patients to specialized facilities, compounded by a shortage of qualified personnel. It underscores the necessity of establishing a network of hospitals equipped with “shock teams” to facilitate prompt intervention and improve patient prognoses [4].

This case highlights the potential for saving critically ill patients experiencing CS. The ultimate unfavorable outcome was not attributable to CS per se but to complications arising from infections during prolonged hospitalization. This highlights the need for continued research focusing on enhancements in the accessibility and efficacy of treatment for such high-risk patients.