Introduction

Pulmonary contusion (PC) is observed in approximately 24–34% of blunt thoracic traumas [1]. It is characterized by the rupture of alveoli, intraalveolar hemorrhage, interstitial edema, and damage to the alveolocapillary membrane. Severe cases can progress to acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which are associated with high morbidity and mortality. Due to the lack of targeted therapies, experimental and clinical research on lung contusion continues to the present time.

Glutamine is the most abundant amino acid in the body and plays a critical role in nitrogen transport, immune function, and pH regulation [2]. It has been shown to inhibit neutrophil migration and also total protein concentrations in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid in a rat model of ALI [3].

L-arginine plays a significant role in the metabolic, immune and reparative response following trauma. As the sole substrate for nitric oxide synthase, it is essential for the production of nitric oxide (NO), a key regulator of cellular metabolism that exerts its effects via cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) [4]. Nitric oxide has several physiological effects such as vasodilation, inhibition of platelet aggregation, neutrophil adhesion and suppression of xanthine oxidase (XO) activity [5]. Under catabolic conditions such as hemolytic anemia, burns, sepsis, and trauma, endogenous arginine synthesis decreases [6, 7]. Therefore, arginine supplementation may be beneficial particularly during oxidative stress, as it helps maintain T-cell function and reduce the risk of infection [8].

Aim

This study aimed to evaluate the histopathological effects of early glutamine and/or arginine administration, which plays an important role in the immuno-inflammatory response for the reduction of inflammation following experimental pulmonary contusion.

Material and methods

This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Dokuz Eylul University (Protocol No: 23/2020). Thirty male Wistar Albino rats (mean weight 441 g; range 405–493 g) were housed under standard laboratory conditions (21–23°C, 12-hour light/dark cycle). The rat model was used due to its easy availability, reliable results, and high reproducibility.

Rats were randomly assigned to five groups (n = 6 each):

Group I (sham): no trauma or treatment;

Group II (trauma control): pulmonary contusion induced under anesthesia followed by intraperitoneal 0.9% saline (4 ml/day) for 3 days;

Group III (glutamine): 200 mg/kg/day glutamine in 0.9% saline, intraperitoneally for 3 days [9];

Group IV (arginine): 200 mg/kg/day arginine in 0.9% saline, intraperitoneally for 3 days [10];

Group V (combined): glutamine (200 mg/kg/day) + arginine (150 mg/kg/day) in 0.9% saline, intraperitoneally for 3 days.

Anesthesia, trauma, and pulmonary contusion

All rats included in the study were weighed prior to experimental procedures. Anesthesia was administered intraperitoneally using 80 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride and 8 mg/kg xylazine. Throughout the procedure, the rats remained under anesthesia with spontaneous respiration preserved.

Pulmonary contusion was induced by the free-fall impact of an aluminum cylindrical weight dropped through a vertically aligned stainless steel tube fixed on a platform (Figure 1). This was based on a modified version of the isolated bilateral pulmonary contusion model originally described by Raghavendran et al. [11]. The kinetic energy (E) imparted during impact was calculated using the standard equation E = mgh, where m represents mass (in kilograms), g is the gravitational acceleration (9.8 m/s²), and h denotes the height (in meters) from which the weight was dropped. Friction forces were considered negligible. With a mass of 180 g and a drop height of 110 cm, the calculated impact energy delivered to the chest wall was 1.94 joules.

Following trauma induction, oxygen therapy (Gez Oxyhome Oxygen Concentrator) was administered at a flow of rate 2 l/min (Figure 2). After trauma, all rats had unrestricted access to food and water, and their nutritional and hydration requirements were closely monitored. No limitations were imposed on feeding or fluid intake during the post-trauma period.

Histopathologic evaluation

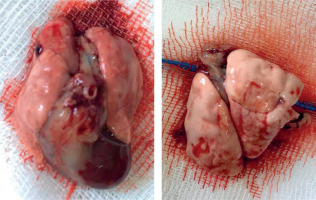

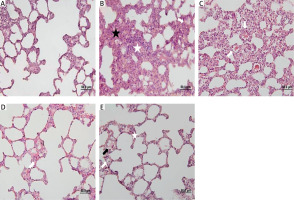

Subjects in all groups were sacrificed on the third day after trauma. The right lung tissue was divided from the main bronchus and the tissues were placed in 10% formalin (Figure 3). The samples were kept in formalin for 48 hours and fixed. After fixation, they were processed with 70% alcohol, 95% alcohol, and 100% alcohol in the dehydration stage, xylene in the transparency stage, and paraffin in the infiltration stage. The samples were embedded in hard paraffin blocks. Rotary microtome (RM 2255, Leica) was used to obtain 5-μm thick sections. Each section was stained with hematoxylin-eosin stain to evaluate the general histomorphological features of the tissue (Figure 4).

For each subject in the experimental groups, lung specimens were obtained from five regions of the right lung. Parenchymal inflammation, alveolar congestion, and alveolar hemorrhage were evaluated semiquantitatively according to intensity. Histologic damage was scored between 0 and 3 for each parameter (0: no change, 1: slight damage < 25%, 2: moderate damage 25–50% and 3: severe damage > 50%).

Parenchymal inflammation score: based on cell density. Grade 0 – no inflammation, Grade 1 – slight damage < 25%, Grade 2 – moderate damage 25–50%, Grade 3 – severe damage > 50%.

Intraalveolar hemorrhage score: Grade 0 – no hemorrhage, Grade 1 – focal hemorrhage, Grade 2 – patchy (foci smaller than 5 magnification fields, but multifocal), Grade 3 – diffuse (across 5 large magnification fields).

Alveolar congestion score: Grade 0 – no alveolar congestion, Grade 1 – focal alveolar congestion, Grade 2 – patchy (foci smaller than 5 magnification fields, but multifocal) Grade 3 – diffuse (across 5 large magnification fields).

Results

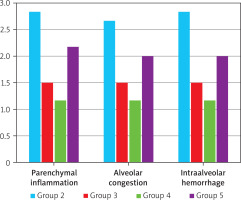

In the comparative histopathological evaluation, no inflammation, alveolar congestion, or intraalveolar hemorrhage was observed in the sham group (Group I) (Grade 0). In contrast, the trauma group (Group II) exhibited the most severe histopathologic changes across all parameters (Grade 3). The treatment groups – glutamine (Group III), arginine (Group IV), and combined glutamine + arginine (Group V) – showed notable reductions in histopathologic scores compared to the trauma group. All treatment groups exhibited significantly lower scores for inflammation, alveolar congestion, and hemorrhage (p < 0.05) (Table I).

Table I

Histopathological scores (mean ± SD, min.–max.). Statistically significant differences were observed between Group 2 and Groups 3, 4, and 5 for all parameters. Additional significant differences were observed between Groups 3 and 5 (parenchymal inflammation), and between Groups 4 and 5 (all parameters)

No statistically significant difference was found between the glutamine-only and arginine-only groups (p > 0.05), suggesting similar efficacy. However, glutamine monotherapy was more effective than combined treatment in reducing parenchymal inflammation (p < 0.05) (Figure 5). Notably, arginine monotherapy was significantly superior to combined therapy in all three histopathologic parameters (p < 0.05) (Table II).

Table II

Pairwise statistical comparisons (p-values)

| Groups | Parenchymal inflammation P-value | Alveolar congestion P-value | Intraalveolar hemorrhage P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 – Other groups | < 0.05* | < 0.05* | < 0.05* |

| Group 2 – Groups 3, 4, 5 | < 0.05* | < 0.05* | < 0.05* |

| Group 3 – Group 4 | 0.241 | 0.241 | 0.241 |

| Group 3 – Group 5 | 0.043* | 0.171 | 0.171 |

| Group 4 – Group 5 | 0.006* | 0.026* | 0.026* |

Discussion

This study investigated the therapeutic effects of glutamine and arginine on histopathological parameters in a rat model of pulmonary contusion induced by blunt thoracic trauma. Our findings confirmed that both agents, when administered individually, reduced inflammation, intra-alveolar hemorrhage, and alveolar congestion effectively.

Previous studies have demonstrated that pulmonary contusion triggers an acute inflammatory response within 24 hours, characterized by increased neutrophil infiltration. By 48 hours, subacute changes such as lymphocyte infiltration and alveolar edema become apparent [12].

Our findings support these pathophysiological timelines. Nutrition-immunity interaction gained attention especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the potential role of amino acid-based support [13]. The anti-inflammatory properties of glutamine have been demonstrated in several studies. Recent studies also confirm glutamine’s protective effects on alveolar epithelial regeneration during lung injury [14]. For example, Oliveira et al. reported that intravenous glutamine (0.75 g/kg) significantly improved alveolocapillary membrane integrity and oxygenation while reducing neutrophilic infiltration and alveolar collapse [15]. Similarly, our study demonstrated significant reductions in inflammatory damage following intraperitoneal glutamine administration. Moreover, glutamine has been shown to reduce lung inflammation in LPS-induced injury models as well [16].

L-arginine, a precursor of nitric oxide, enhances immune function and improves microcirculatory dynamics under stress conditions. Additionally, arginine supplementation has been shown to support immune cell signaling and reduce inflammatory and septic responses [17, 18]. Dong et al. showed that arginine-treated rats had lower wet/dry lung ratios and better-preserved pulmonary histology after contusion [19]. In another study, L-arginine was found to prevent pulmonary neutrophil accumulation and preserve endothelial function following endotoxemia [20]. Our study also showed near-normal alveolar architecture and significantly improved histopathological scores in the arginine group, confirming its potent protective effect.

Interestingly, the combined glutamine and arginine treatment was less effective than either agent used alone. This may be attributed to competitive or antagonistic metabolic pathways, as both amino acids influence similar immune and inflammatory cascades [21]. A similar finding was reported in a recent animal study, where combined L-arginine and L-glutamine supplementation improved immune response but did not enhance overall physiological outcomes [21]. These findings suggest that while each amino acid may have beneficial effects individually, their combination does not necessarily lead to additive outcomes and may, under certain physiological conditions, limit each other’s efficacy. To our knowledge, such antagonistic behavior in the context of pulmonary contusion has not been previously reported and warrants further investigation.