Introduction

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a common disorder in women characterized by polycystic ovarian morphology, excess androgen production, and ovulatory dysfunctions. Besides obesity, PCOS is closely and strongly associated with metabolic dysfunctions including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, and abnormal glucose metabolism, which elevates the risk of developing PCOS-associated metabolic disorders, including diabetes mellitus and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [1], a condition of abnormal/excessive fat (mainly triglycerides – TG) accumulation in the local tissues of the patient’s liver in addition to documented histological steatosis in > 5% hepatocytes [2].

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) – a chronic intermittent/interrupted hypoxia that involves narrowing of a patient’s upper airways during his/her sleeping times, causing fragmented sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, and low quality of life – is a common sleep disordered breathing among PCOS women with overweight and/or obesity. It should be noted that PCOS females had a thirty-fold higher risk of OSA than healthy age-matched females. Besides hypertension, left untreated, OSA is usually responsible for the development of metabolic derangements including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, abnormal glucose metabolism, and NAFLD (frequency of NAFLD is at least twice that in healthy females without PCOS) [3]; hence, treatment of OSA might be beneficial for NAFLD and vice versa in obese women with PCOS [4].

Since there is no current effective pharmacologic treatment for NAFLD [2] or PCOS [5], weight loss (by diet restriction alone or combined with increasing energy expenditure) is the main therapy for NAFLD [2] and PCOS [6], because it improves NAFLD-associated insulin resistance, liver dysfunctions, and dyslipidemia [2] in addition to the improvement in PCOS-associated excess androgens, abnormal levels of sex hormones, and ovarian functions [6]. Also, weight loss is one of the main therapeutic approaches in OSA patients, because it positively improves apnea frequency, daytime sleepiness, insulin resistance, during-sleep upper airway collapse, associated metabolic co-morbidities, and fat deposition in the neck area [7].

According to our limited best knowledge, no published study has examined the role of weight loss (via diet restriction alone or combined with regular aerobic exercise) in PCOS women with NAFLD and OSA, so this study aimed to assess the effect of lifestyle modification on liver enzymes, TG, sex hormones, and daytime sleepiness in PCOS women with OSA and NAFLD.

Material and methods

Settings

Paper posters urging any woman suffering from PCOS, NAFLD, and OSA to join this study were pasted on the walls of the outpatient clinics of a local general hospital (Mit Ghamr Hospital) affiliated with the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population.

Ethics

The usual approvals to conduct scientific research, both from the participating PCOS women and the Scientific Research Ethics Committee (Cairo University, P.T./REC/012/005321), were obtained while following international recommendations (Helsinki guidelines) in this regard. This study (NCT06591169), registered at www.clinicaltrial.gov, was conducted 5th July – 15th December 2024.

Inclusion criteria

The age of the 40 included PCOS women with OSA and NAFLD ranged 30–40 years. The body mass index (BMI) of the included PCOS women with NAFLD and OSA ranged from ≥ 30 to ≤ 40 kg/m2. The diagnosis of NAFLD was confirmed using ultrasonography (by a gastroenterologist). Non-pregnant women without smoking history or breastfeeding were included.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome women with mild to moderate OSA who had just received their diagnosis of OSA and refused continuous positive airway pressure therapy met the inclusion criteria. The diagnosis of OSA was performed via a referral from a respiratory physician to the staff of a local laboratory for sleep studies. According to the applied sleep study, women with > 5 to ≤ 30 events/hour on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) were diagnosed. Apnea-hypopnea index is an indicator of the severity of sleep apnea which was determined by counting or estimating the number of apneas and hypopneas during sleep.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome was diagnosed by a certified gynecologist based on the Rotterdam consensus, which required the presence of at least two of the following criteria: ovarian cysts, monthly irregularity of women’s menstrual cycle, and hyperandrogenism (clinical and/or biochemical) [8].

Exclusion criteria

Patients with peripheral arterial disease, systemic disorders (e.g. diabetes mellitus), metabolic syndrome, hypertension, cardiac diseases, thyroid disorder, renal dysfunction/disorders, orthopedic disorders of the lower limb that would prohibit regularity of walking exercise, history of psychiatric or neurodegenerative/neurogenic disorders, other hepatic/respiratory problems, history of exercising or following diet protocol less than six months, history of malignancies, gynecological congenital anomalies, a recent history of fertility or contraceptive drugs, local gynecological/uterine problems other than PCOS, or hyperprolactinemia, or pituitary gland tumors (presence of tumors was confirmed by the consistent radiological imaging) were excluded.

Randomization

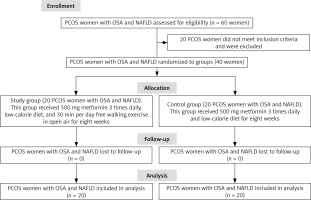

An independent researcher who was a nurse holding a PhD executed the randomization process of this trial (Fig. 1). The data of patients and details of interventions were not explained to this nurse. The nurse randomly assigned PCOS women (n = 40) with OSA and NAFLD to the study and control groups (n = 20 for each PCOS group). Besides the low-calorie diet (LCD), both PCOS groups received 500 mg with-meal metformin tablets which were consumed three times daily (the trade name of this medicine in the Egyptian market was Cidophage, CID pharma, Cairo, Egypt).

Fig. 1

Flow chart of polycystic ovarian syndrome women with obstructive sleep apnea and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease NAFLD – nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, OSA – obstructive sleep apnea, PCOS – polycystic ovarian syndrome

It must be noted here that the long-term use of this drug is associated with disappearance of its gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea [9] (at early use, this issue was demonstrated by the treating physician to all females to ensure women’s regular use of 3-time tablets daily. Moreover, regular calls and follow-ups were made by authors daily to affirm the adherence of patients to the administration of medications). The study group additionally received free 30-minute walking exercise daily. The total duration of this interventional trial was eight weeks. The randomization method was the closed envelope method.

Low-calorie diet

Every PCOS woman with OSA and NAFLD was given a well-balanced detailed LCD consisting of three main meals daily. Every LCD plan was individualized to every PCOS woman based on her required/recommended intake of nutrients. The intended calories supplied to every PCOS woman in this trial were calculated from subtraction of 500 calories from every woman’s basal metabolic rate. Besides fruits, dietary fibers, and vegetables, macronutrients of the recommended meals included lipids/fats (20–30%), sources of proteins (10–15%), and sources of carbohydrates (55–65%). The authors designed a schedule of weekly interviews with both groups of PCOS women with OSA and NAFLD to track, discuss, and gauge their compliance with the recommended information of LCD [10].

Free walking exercise

At each session, PCOS women with OSA and NAFLD were required to commit to a half-hour free walking exercise in the open air, seven days a week for eight weeks. If the woman had government or private employment, the free walking session was held outside of her regular working hours. In order for the patients to finish the suggested walking program, their walking pace needed to be less than 60% of their target heart rate. A wristband heart rate monitor was used to track each woman’s heart rate. The study’s authors oversaw the daily free walking sessions of PCOS women with NAFLD and OSA by using the Imo video calling program (this program was downloaded to women’s phones to facilitate the program’s use).

Outcomes

Besides aspartate transaminase (AST, as the primary outcome), alanine transaminase (ALT), and TG, the following outcomes were assessed in all PCOS women with OSA and NAFLD: waist circumference (WC), neck circumference (NC), BMI, waist-hip ratio (WHR), serum testosterone (assessed via commercial RIA enzymatic kits, Diagnostic Systems), serum dehydroepiandrosterone (assessed via Roche-Cobas-e601, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), ratio of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone (LH : FSH ratio), and AHI.

Also, the Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS, a valid scale that was used to evaluate excessive daytime sleepiness in OSA patients) was assessed before and after eight weeks [11].

Blinding

No interventional data were explained to assessors of outcomes (BMI, ESS, ALT, LH : FSH ratio, WC, dehydroepiandrosterone, NC, WHR, AHI, testosterone, AST, and TG).

Sample size calculation

The effect size (d = 1 at a power of 80%) of AST (this liver enzyme was the primary outcome conducted on 16 pilot-test PCOS women with OSA and NAFLD) directed the author to the need of 17 women in every group. This was obtained during the authors by-G*Power sample size calculation. To account for dropout, an additional 18% of the sample (34 women) was required, so an additional 3 women were added to each group.

Statistical analysis

The statistical test, repeated-measure ANOVA, was used to analyze the significant between-group or within-group changes in outcomes (BMI, ESS, ALT, LH : FSH ratio, WC, dehydroepiandrosterone, NC, WHR, AHI, testosterone, AST, and TG) using SPSS 18 at a p-value < 0.05, because all outcomes were normally distributed, according to the results of the Shapiro test. Also, because the BMI and age of PCOS women with OSA and NAFLD were normally distributed, the pre-treatment between-group significance was tested via the unpaired test.

Results

The pre-treatment comparison of women’s physical and demographic characteristics (WC, WHR, age, NC, and BMI) between groups did not reveal any significant difference as shown in Table 1. Also, the pre-treatment comparison of women’s outcomes (BMI, ESS, ALT, LH : FSH ratio, WC, dehydroepiandrosterone, NC, WHR, AHI, testosterone, AST, and TG) between groups did not reveal any significant difference, as shown in Table 2.

Table 1

Data (basic/demographic) of polycystic ovarian syndrome women with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obstructive sleep apnea

Table 2

Outcomes of polycystic ovarian syndrome women with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obstructive sleep apnea

The within-group comparison of outcomes (BMI, ESS, ALT, LH : FSH ratio, WC, dehydroepiandrosterone, NC, WHR, AHI, testosterone, AST, and TG) showed a significant improvement in both PCOS groups, but the improvements were larger in the study group, as shown in Table 2. Also, the between-group comparison of post values of outcomes (BMI, ESS, ALT, LH : FSH ratio, WC, dehydroepiandrosterone, NC, WHR, AHI, testosterone, AST, and TG) showed a significant improvement in the study group, as shown in Table 2.

Discussion

This is the first study to report a significant improvement in BMI, ESS, ALT, LH : FSH ratio, WC, dehydroepiandrosterone, NC, WHR, AHI, testosterone, AST, and TG after 8-week lifestyle changes in PCOS women with NAFLD and OSA.

Weight loss (via exercise and/diet restriction) is usually associated with improved insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, which are responsible for excess body mass, dyslipidemia, increased androgen production, inhibited production/release of sex-hormone-binding globulin, low reproductive and ovarian functions, and infertility [6, 12]. This may explain the observed improvement in the levels of sex hormones in this study.

Exercise (aerobic form) is usually associated with triggering biochemical substances that evoke a series of physiological stimuli that enhances muscular oxygen uptake [13, 14], increase oxidation of fats (mainly free fatty acids), increase the burning process of fat, decrease local fat deposits (especially visceral fat deposits) and TG, increase tissue sensitivity to insulin, utilize circulating glucose as an energy source, and decrease excess body mass [15, 16]. This may explain the reported improvement in TG and anthropometric measures in this study.

The significant improvements in the levels of TG, dehydroepiandrosterone, BMI, testosterone, WC, and LH : FSH ratio after 12 weeks of ketogenic diet in PCOS women were consistent with our results [17]. Also, consistent with us, the reduction of carbohydrate intake for 45 days in PCOS women significantly improved their LH : FSH ratio, testosterone, BMI, WC, and WHR [18]. Consistent with the presented data, in obese girls with PCOS who achieved weight loss, 1-year lifestyle changes (diet and exercise therapy) significantly improved BMI, testosterone, WC, dehydroepiandrosterone, and TG [19]. Also, exercise for 3 months significantly enhanced weight, testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone, LH : FSH ratio, and TG in overweight and obese adolescents and young females with PCOS [20]. The results of Pilates exercise in PCOS women in the study published in 2020 agreed with our results, because there was a significant improvement in LH, FSH, testosterone, and weight [21]. Also, 12-week intensified aerobic exercise in PCOS women significantly improved their BMI and TG [22]. Lifestyle changes for eight weeks in PCOS women with overweight and obesity significantly enhanced weight loss, body fat, and reproductive measures (LH : FSH ratio and testosterone) [23].

In contrast, the limited nutritional control was the suggested cause of the non-significant improvement in dehydroepiandrosterone, BMI, testosterone, and WHR after the 8-week running program in PCOS women [24]. Despite the significant reduction in WC and WHR, dehydroepiandrosterone and testosterone did not significantly decrease after the performed 12-week aerobic training program in PCOS women [25]. Also, despite the non-significant decrease, LH : FSH ratio and testosterone did not significantly change in response to nutritional counseling alone or combined with exercise training for 12 weeks in PCOS women due to the limited number of women (six women were involved in the intervention of nutritional counseling and six women were involved in the intervention of exercise training combined with nutritional counseling) [26].

On the other hand, regarding the better values of liver enzymes after exercise training, exercise-induced higher production of anti-inflammatory biomarkers, enhanced resistance to additional inflammation of newly formed hepatocytes, enhanced immune system activity, and restored normal functioning of the hepatic tissue to be able to confront, limit, or prevent steatosis [27, 28] may all contribute to the better values of liver enzymes (ALT and AST) observed in this study.

In line with the present results, adding aerobic exercise to diet restriction for eight weeks in ten women with NAFLD significantly improved their ALT and AST [29]. Also, the performance of regular exercise training for 6 weeks in NAFLD women significantly improved their AST, TG, and ALT levels [30]. Due to improved inflammatory cytokine levels, liver enzymes (assessed as ALT and AST) significantly improved after 12 weeks of aerobic exercise in 25 patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis [31].

Regarding the improved OSA parameters (ESS and AHI), it is postulated that increased testosterone levels elevate breathing instability and apneic threshold during sleeping [3]. Improved testosterone levels after the applied lifestyle changes in this study may have contributed to the changes in breathing instability and apneic threshold during sleeping, which were tested via AHI in this study.

Furthermore, it is documented that there is a strong correlation between the overall mass of the patient’s body, the distribution of body fat, and the elevated risk of OSA. Also, it is documented that there is a strong correlation between the amount of visceral fat, the risk of OSA [3], OSA-associated upper airway collapse [32], and OSA-associated repeated frequency of apnea and daytime sleepiness [3]. Improved BMI, WC, and WHR after the applied lifestyle changes in this study may be the cause of the improved OSA-related parameters [33, 34] including AHI and ESS.

Increased fluid displacement around OSA women’s neck area during sleep, even for a short period of sleep, may be the cause of airway collapse that evokes the low quality of sleep in patients with OSA. The strong role of aerobic exercise in regulating fluid dynamics and shifting fluid accumulation away from the neck area may be the cause of improved sleeping quality and reduced excessive daytime sleepiness [35, 36].

Also, the enhanced exercise-induced control of the hypothalamus [37] over the body temperature of an exercised subject elevates the temperature of his/her body after the aerobic exercise, improving the onset of sleep and interrupted sleeping [38, 39].

In line with the findings, a 24-week lifestyle modification program significantly lowered the BMI, TG, and ALT of OSA patients [40]. Additionally, gamma-glutamyl transferase (as a liver enzyme), TG, BMI, NC, and ESS of OSA patients were dramatically improved by a weight-loss program that included LCD, aerobic exercise, and resistive exercise for 16 months [41]. Once more, sleep breathing difficulties/disorders and related metabolic dysfunctions, such as NAFLD, could be lessened or eliminated after three months of non-surgical weight-loss therapy/program [42].

According to Desplan et al. [43], who partially agree with us, OSA patients who underwent a month of exercise training saw a significant improvement in their ESS but not in their TG. Additionally, despite the partial support of BMI and ESS after 6-month lifestyle changes in a study conducted in 2020 on OSA patients, the results of TG, AST, and ALT of those patients opposed our results, because the results did not significantly improve due to the lack of direct supervision over the applied lifestyle changes [44].

Despite the non-significant changes in BMI, NC, WC [31, 44], and ESS [32] in OSA patients, 12-week aerobic exercise (3 times weekly) showed significant improvement in AHI [32, 45]. Also, despite a decrease in AHI after 16 weeks of lifestyle changes (LCD, aerobic exercise, and resisted exercise), it did not reach a significant improvement, possibly due to the low number of included patients with OSA (n = 10) in the study.

Limitations

The lack of long-term follow-up of BMI, ESS, ALT, LH : FSH ratio, WC, dehydroepiandrosterone, NC, WHR, AHI, testosterone, AST, and TG was the main limitation in the study on women with PCOS, NAFLD, and OSA, so it is important to be covered in future trials.

Conclusions

Adding eight weeks of free walking exercise to LCD and administration of metformin led to significant improvements in BMI, ESS, ALT, LH : FSH ratio, WC, dehydroepiandrosterone, NC, WHR, AHI, testosterone, AST, and TG compared to LCD and administration of metformin alone in PCOS women with NAFLD and OSA.