Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the world, with an estimated 2.26 million cases recorded in 2020, and the leading cause of cancer mortality in women worldwide [1]. About 685,000 women died from the disease, corresponding to 16% or 1 in every 6 cancer deaths in women [2]. Therefore, the early diagnosis of BC is crucial because BC is asymptomatic in the early stages, resulting in late detection of BC, which reduces the patient survival and efficacy of treatment options [3]. Mammography is needed for early diagnosis of BC because it is an effective method in the detection of early-stage breast cancers, reducing mortality rates and improving treatment outcomes [4].

The treatment of BC depends on surgical resection of the breast for invasive breast cancers [5], radiation therapy after surgical resection of BC to destroy or damage any remaining cancer cells [6], endocrine/hormonal therapy to treat hormone receptor-positive invasive BC [7], and chemotherapy before surgery to reduce tumour size and after surgery to treat BC patients with a high risk of recurrence [8].

Unfortunately, the administration of chemotherapeutic agents in BC treatment results in serious side effects, recurrence, and development of multi-drug resistance [9]. Among others, doxorubicin (DOX), also known as Adriamycin, is an anthracycline drug that is considered as one of the most effective chemotherapeutic drugs in the treatment of BC [10]. It is also used in the treatment of solid tumours, ovary, bladder, and lung cancers [11]. Doxorubicin exerts its effect by intercalation with DNA preventing topoisomerase-II activity leading to DNA damage, and formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to oxidative stress, DNA damage, and membrane damage resulting in cell death [12]. Despite its efficacy, it has significant side effects such as cardiotoxicity (which is the most significant), nephrotoxicity, and hepatotoxicity [13].

In our study, we used the Ehrlich solid tumour (EST) as a tumour model, which is widely used in cancer research in animals to investigate the antitumour activities of natural and synthetic compounds because Ehrlich ascites carcinoma (EAC) cells are undifferentiated, grow rapidly, and are 100% malignant. The solid tumour is generated in mice by subcutaneous injection of the EAC cells [14].

Because of the several limitations of chemotherapeutic medications, it is important to identify and use alternative therapies with potent antitumor activity and lower side effects. Interestingly, Phytochemicals are natural compounds isolated from plants and used for the prevention and treatment of various diseases, including cancers. The antitumour activity is achieved by interfering with the development and progression of cancer through modulation of several mechanisms such as proliferation, angiogenesis, and apoptosis [15]. Moreover, natural products can also mitigate the side effects of chemotherapy administration [16].

Ferulic acid (FA) is a phenolic compound extracted from Ferula foetida, commonly found in the trans-isomeric form and abundant in rice, wheat, grains, vegetables, fruits, coffee seeds, and nuts [17]. It has many biological activities such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antimicrobial, hepatoprotective, and cardioprotective [18]. It exerts its anticancer activity by various mechanisms: inhibition of cell proliferation by blocking PI3K/AKT pathway, induction of apoptosis and autophagy by increasing the levels of caspase-3, Beclin-1, and LC3-II biomarkers, and suppression of angiogenesis by downregulating vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) expression in cancer cells [19]. Moreover, FA can reduce oxidative stress by decreasing malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and increasing total antioxidant capacity (TAC) [20]. Because FA is poorly water-soluble, its oral bioavailability is reduced, limiting its biological activity and clinical applications. Nanotechnology is one approach used to address this issue [21]. Therefore, nanosuspension technology can be used not only to increase the solubility but also to improve the bioavailability and efficacy of FA [22].

The present study aimed to evaluate the antitumour effect of FA and nanosuspension (FA-NS) alone and in combination with DOX on Ehrlich solid tumours to investigate the expected therapeutic synergy of FA and/or FA-NS with DOX by the determination of inhibition or induction of PI3K/AKT pathway or proliferation by estimation of AKT, autophagy by estimation of Beclin-1 and LC3-II expressions, apoptosis by estimation of caspase-3, and angiogenesis by estimation of VEGFR-2 levels. Moreover, we aimed to evaluate the expected protective effect of FA against different toxicities induced by DOX administration through the estimation of the levels of TAC and MDA to assess oxidative stress, troponin-1 (Tn1) and creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) to assess cardiotoxicity, alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) to assess hepatotoxicity, urea and creatinine to assess nephrotoxicity, histopathological and immunohistochemical studies, and to investigate the underlying mechanisms and pathways of FA in breast cancer.

Material and methods

Ethical concerns

The study was approved by the Animal Care and Ethical Committee at the faculty of pharmacy, Damanhour University (Reference no:1021PB24).

Reagents and chemicals

Ferulic acid 99% (Sigma-Aldrich, catalogue no. 128708-5G). Doxorubicin (Hikma Specialized Pharmaceuticals company, Batch no. 210117). Solvents used for FA-NS (sodium lauryl sulphate, tween 80, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and acetone) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK. The parent lines of EAC cells were obtained from the Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University, Egypt. All other required chemicals were supplied in analytical grades from suitable commercial sources.

Preparation of ferulic acid-loaded nanosuspension

Ferulic acid-NSs were prepared by a solvent evaporation antisolvent precipitation method using probe sonication [23, 24]. Ferulic acid was dissolved in acetone to prepare a stock solution of 60 mg/ml. Aqueous PVA solution (0.5% w/w) was prepared separately as the antisolvent solution. Tween 80 and ionic surfactant (SLS) were investigated as co-stabilisers, as illustrated in Table 1. The drug solution was added dropwise over one minute into the antisolvent stabiliser solution under probe sonication (QS4 system, NanoLab, Waltham, MA, USA), which was continued for 15 min (3 cycles each of 5 min) at an amplitude of 80% (of 125 W, 20 KHz) with 10 s pulse on and 5 s pulse off. The sonication was performed in an ice bath to maintain the temperature of the stabiliser solution at 5 ±3°C. This drug dispersion was then allowed to precipitate in nanosized form by solvent evaporation at ambient temperature conditions under magnetic stirring. The prepared formulations were stored in the fridge at 2–8ºC.

Physicochemical properties of NS-preparation

Particle size and zeta potential measurement

Nanosuspension preparations were characterised for particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential analysis by dynamic light scattering using a Microtrac particle sizer and zeta potential analyser (Microtrac Retsch Gmbh, Haan, Germany). The measurements were performed at 25°C after proper dilution (1 : 100) with deionised water.

Drug content homogeneity

To evaluate the drug content homogeneity (DCH%) in FA-NS, an aliquot of 100 µl of the prepared NS was evaporated overnight to dryness [25, 26]. The residue was dissolved in acetone and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min. Then, samples were filtered through a 0.20 µm filter and analysed spectrophotometrically at 325 nm using a UV spectrophotometer T80 UV–Vis 1800 (PG Instruments Ltd., UK). The drug content homogeneity percentage was estimated according to the following equation [26, 27]:

Stability of ferulic acid nano suspension

Ferulic acid nanosuspension were stored at 2–8°C for 2 months and subjected to stability study by monitoring any change in particle size, zeta potential, and DCH%.

Animwlthy and nonpregnant female Swiss albino mice (30 gm), were obtained from the Animal Care Unit of the Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University, Egypt. The mice were housed in polyethylene cages (5 per cage) under controlled laboratory conditions (25 ±1°C, constant relative humidity (about 50%), and an alternating 12 hour dark/light cycle). Food and water were provided ad libitum. All mice were allowed to adapt for one week before the beginning of the study.

Tumour induction

Ehrlich ascites carcinoma cells were injected intraperitoneally (i.p) into mice. The ascitic fluid was withdrawn after 7–10 days from Ehrlich carcinoma (EC)-bearing mice [28]. The ascitic fluid containing EAC cells was suspended in sterile normal saline solution, and 0.2 ml of the suspension containing 2.5 million EAC cells was injected subcutaneously (s.c) into the mammary fat pad on the upper left ventral side of the mice [29]. Trypan blue dye exclusion technique was used to test the viability of EAC cells. All steps of EAC cell aspiration and injection were under aseptic conditions to avoid contamination. After 10 days of tumour induction, solid tumours appeared, confirmed using a caliper, and then the therapeutic protocols were started [30].

Experimental design

Thirty-five female Swiss albino mice were divided into 7 groups, with 5 mice in each group. Group1 (control): normal or healthy mice were injected (i.p) with normal saline (0.1 ml/mouse, day, i.p) for 21 days [31]. Group 2 (EST): Ehrlich solid tumour-bearing mice were injected (i.p) with normal saline (0.1 ml/mouse, day, i.p) for 21 days [20]. Group 3 (FA): EST-bearing mice were treated with oral injection of FA (100 mg/kg/day, p.o) for 21 days [32]. Group 4 (FA-NS): EST-bearing mice were treated with oral injection of FA-NS (40 mg/kg/day,p.o) for 21 days [33]. Group 5 (DOX): EST-bearing mice were treated with i.p injection of DOX (2 mg/ kg/day, i.p) for 21 days [34]. Group 6 (FA + DOX): EST-bearing mice were treated with a combination of oral injection of FA (100 mg/kg/day) and (i.p.) injection of DOX (2 mg/kg/day, i.p) for 21 days. Group 7 (FA-NS + DOX): EST-bearing mice were treated with a combination of oral injection of FA-NS (40 mg/kg/day) and (i.p.) injection of DOX (2 mg/kg/day, i.p.) for 21 days.

At the end of the experiment, mice were euthanised by ether inhalation [35], and blood samples were collected from the orbital sinus. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes. Serum was separated and stored at –80oC until analysis. Solid tumours and organs (heart, liver, and kidneys) were removed. Solid tumours were weighed, cleaned in normal saline, and then divided into 2 parts; the first part was stored at –80oC for DNA examination, and the second part was fixed in 10% formalin solution to be ready for histopathological and immunohistochemical investigation [36].

Estimation of AKT, Beclin-1, and LC3-II by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

RNA extraction from solid tumour tissues was performed using RNeasy® Mini Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, QIAGEN Strasse 1, 40724 Hilden, GERMANY, Catalogue no. 74104), following the manufacturer’s protocols. cDNA was synthesised from extracted RNA using a RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., USA, Catalogue no. K1622), following the manufacturer’s protocols. The resulting cDNA was mixed with AKT, Beclin-1, and LC3-II primers (Table 2) using Maxima SYBER Green quantitative polymerase chain reaction Master Mix (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., USA, Catalogue no. K0251), following the manufacturer’s protocols. AKT, Beclin-1, and LC3-II gene expressions were analysed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction amplification was performed under the following thermal cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95oC for 10 min, then denaturation at 95oC for 15 s repeated for 40 cycles, then annealing with primer at 60oC for 30 s, then extension at 72oC for 30 s. All experiments were repeated 3 times. Relative gene expression levels of Beclin-1, AKT, and LC3-II were compared to β-actin as a house-keeping gene. Then the cycle threshold data were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method [37].

Table 2

Primers sequences for AKT, Beclin-1, LC3-II, and β-actin genes

Estimation of caspase-3, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, total antioxidant capacity, and malondialdehyde

The level of caspase-3 was measured by using a mouse caspase-3 ELISA kit (My BioSource, Inc., USA, Catalogue no. MBS733100). The level of vascular endothelial VEGFR-2 was measured by using a Mouse VEGFR-2 ELISA kit from (Fine Biotech Co., Ltd, Wuhan, China, Catalogue no. EM1445). The level of TAC was measured by using a mouse TAC ELISA kit (My BioSource, Inc., USA, Catalogue no. MBS733680). The level of MDA was measured by using a MDA Colorimetric Assay Kit (TBA method) (Elabscience, Catalogue no. E-BC-K025-M). Each procedure was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Estimation of troponin-1 and creatine kinase-MB

The level of Tn1 was measured by using a Mouse Troponin-1 ELISA kit from (Abcam, China, Catalogue no. ab285235), and the level of CK-MB was measured by using a Mouse CK-MB ELISA kit from (Novus bio, Catalogue no. NBP2-75312), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Estimation of creatinine and urea

The level of creatinine was measured using the Mouse Creatinine kit obtained from (Crestal Chem, Inc., USA, Catalogue no. 80350), and the level of urea was measured using a colorimetric detection kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., USA, Pub. no. MAN0025406), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Estimation of alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase

The levels of ALT and AST were measured by using commercial kits according to the method of Bergmeyer et al., 1980 and Bergmeyer et al., 1976, respectively [38].

Immunohistochemical analysis

The immunohistochemical technique in tumour sections was investigated according to the method described by [39]. Briefly, 4-µm-thick paraffin sections were prepared, deparaffinised by xylene, rehydrated in graded alcohols, then washed with distilled water. After washing with distilled water, deactivation of endogenous peroxidase was performed using 3% H2O2 in absolute methanol for 5 min at 4°C. After washing with phosphate buffer saline (PBS), the nonspecific reaction was blocked with 10% normal blocking serum for 60 min at room temperature. Then, the primary antibody (polyclonal antibody against VEGFR [BioGenex, USA, catalogue no. AR483–5R]) was incubated at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antiserum (Histofine kit, Nichirei Corporation) for 60 min. Then they were washed in PBS, followed by incubation with streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate (Histofine kit, Nichirei Corporation) for 30 min. The streptavidin-biotin complex was visualised with 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB)-H2O2 solution, pH 7.0, for 3 min. Then sections were washed in distilled water, and Mayer’s haematoxylin was used as a counterstain. For the quantitative histomorphometric analysis, original micrographs were captured from the immunostained slides (10 random fields from each section, ×100 by a digital camera [Leica EC3, Leica, Germany]) connected to a microscope (Leica DM500). The percentage areas of the immunostaining reaction were counted in each of the examined fields by using ImageJ software (v1.46r, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) [40].

Histopathological investigation and scoring system

After anaesthetising by ether inhalation, the animals were euthanised by cervical dislocation. Tumours, livers, heart, and kidneys were surgically removed and flushed with PBS (pH 7.4), fixed in 4% PFA dissolved in PBS, for 48 hours. The fixed specimens were processed by the conventional paraffin embedding technique including dehydration through ascending grades of ethanol, clearing in 3 changes of xylene and melted paraffin, and ended by embedding in paraffin wax at 65°C. Four-µm-thick sections were stained by haematoxylin and eosin (HE), as previously described by Bancroft and Layton [41]. In each excised tumour, the semi-quantitative scoring of necrosis was assessed in 10 random fields (40×). The scoring scale ranged 1–4: Score 1 – about 10% necrosis was shown in poorly differentiated neoplasm; Score 2 – about 25% necrosis was shown in poorly differentiated neoplasm; Score 3 – about 35% necrosis was shown in poorly differentiated neoplasm; and Score 4 – more than 50% necrosis was shown in poorly differentiated neoplasm. The mean value of all scores (10 fields/tumour sample) was recorded, analysed, and expressed as the mean of the necrosis scale ± S.E. In relation to histopathological lesion scores in kidney, heart, and liver, semiquantitative scoring of renal and hepatic lesions was calculated according to [42]. Briefly, lesions in 10 fields chosen randomly from each slide for each rat were obtained and averaged. The lesions were scored in a blinded way (score scale: 0 = normal; 1 ≤ 25%; 2 = 26–50%; 3 = 51–75%; and 4 = 76–100%).

Results

Tumour weight

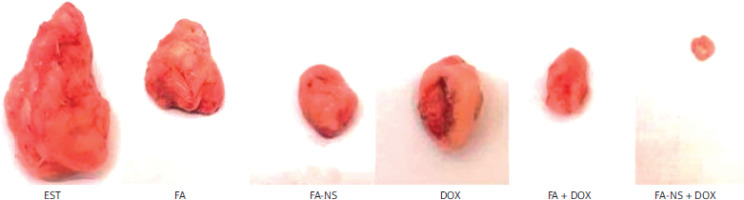

As expected, the EST group showed the highest increase in tumour weight (g), whereas all treated groups including FA (1.89 ±0.69), FA-NS (1.16 ±0.39), and DOX (1.45 ±0.65) showed a significant reduction in tumour weight compared to the EST (4.84 ±0.69) group. Furthermore, the combination groups FA + DOX (0.96 ±0.095) and FA-NS + DOX (0.66 ±0.16) showed a more significant reduction in tumour weight compared to the EST (4.84 ±0.69) group. Moreover, the FA-NS (1.16 ±0.39) and FA-NS + DOX (0.66 ±0.16) groups showed a notable reduction in tumour weight compared to the FA (1.89 ±0.69) and FA + DOX (0.96 ±0.095) groups (Figure 1).

Particle size and zeta potential measurement

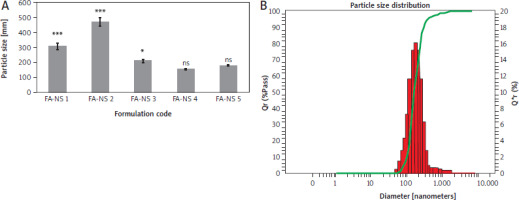

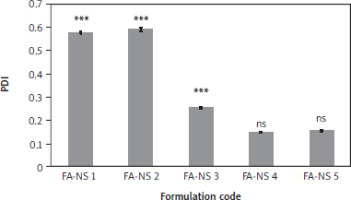

Different FA-NSs were prepared from various combinations of PVA, tween 80, and SLS, as illustrated in Table 1. Particle size, PDI, and zeta potential values were assessed. The obtained particle size distribution and PDI values are shown in Figures 2 and 3. Ferulic acid-NS 4 (3 mg/ml, FA) showed the smallest monomodal particle size of 155.30 ±3.32 nm, PDI of 0.146 ±0.002, and a negative zeta potential of –46.90 ±4.26 mV. Upon increasing the drug concentration into 10 mg/ml in FA-NS 5, particle size recorded 180.65 ±5.40 nm, PDI of 0.153 ±0.004, and a zeta potential of –57.50 ±1.97 mV reflecting an insignificant change in particle size profile and potentiality to form stable NS.

Figure 2

Particle size distribution of nanosuspension of ferulic acid (FA-NS) formulations, means ± SD, n = 3 (A), particle size chart of FA-NS 4 (B) ns – non-significant difference from nanosuspension of ferulic acid 4 *** and * – significant, ns – non-significant difference from nanosuspension of ferulic acid 4 using one-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test.

Figure 3

Polydispersity index of nanosuspension of ferulic acid formulations FA-NS – nanosuspension of ferulic acid, ns – non-significant difference from nanosuspension of ferulic acid 4 Means ± SD, n = 3 *** and * – significant, ns – non-significant difference from nanosuspension of ferulic acid 4 using one-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test.

Drug content homogeneity

An evaporation filtration method was used to evaluate the DCH%. Samples were analysed using spectrophotometric assay. The prepared FA-NS 5 achieved a drug loading of 95.27% ±6.47.

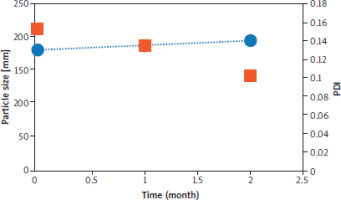

Stability of ferulic acid nano suspension

A 2-month stability study was followed to assess the stability of FA-NS 5. The selected formulation was tested for particle size, PDI, zeta potential values and DCH%. As shown in Figure 4, FA-NS 5 maintained its monomodal particle size distribution and PDI values without significant difference from fresh formulations throughout two months of storage at 2–8°C. Besides, FA-NS 5 kept its negative zeta potential at –60.30 ±1.74 mV and its DCH% at 92.49% ±5.35.

Figure 4

Particle size distribution and polydispersity index values and of nanosuspension of ferulic acid 5 formulations throughout 2 months storage at 2–4°C Blue dots represent particle size (nm) and orange squares represent polydispersity index. Means ± SD, n = 3. ns – non-significant difference using one-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test.

At the end of physicochemical properties tests, FA-NS 5 was selected as the optimum formulation for further characterisation due to homogenous particle size distribution and higher drug loading.

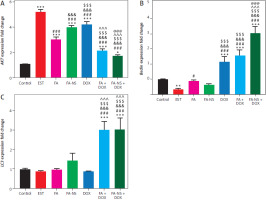

Effect of different treatments on AKT, Beclin-1, and LC3-II expression levels

The AKT expression significantly increased in the EST group compared to the control group. On the other hand, all the treatment groups, including FA, FA-NS, and DOX, as well as the combination groups, showed a significant reduction in the AKT expression compared to the EST group. Furthermore, the combination of FA in normal formulation (FA) and the nano formula (FA-NS) with DOX showed the most significant decrease in AKT expression levels compared to the EST group. Interestingly, the nano formula of FA (FA-NS) with DOX showed a significant decrease in AKT expression levels compared to all other groups (Figure 5A).

Figure 5

AKT, Beclin-1, and LC3-II expressions in Ehrlich solid tumourbearing mice using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Effect of treatment on AKT expression in all studied groups (A), effect of treatment on Beclin-1 expression in all studied groups (B), effect of treatment on LC3-II expression in all studied groups (C) DOX – doxorubicin, EST – Ehrlich solid tumour, FA – ferulic acid, FA-NS – nanosuspension of ferulic acid Gene expression values were normalised against β-actin that was used as the housekeeping gene. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5). Data were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test at p-value < 0.05. *, #, &, $, ^, and @ indicate significant change from control, EST, FA, FA-NS, DOX, and FA + DOX, respectively (* or # represent p < 0.05, ** represent p < 0.01, ***or ### or &&& or $$$ or ^^^ or @@@ represent p < 0.001).

Regarding Beclin-1 and LC3-II expressions, EST group showed a significant reduction in Beclin-1 but comparable in LC3-II as compared to control group, whereas the combination groups FA + DOX and FA-NS + DOX showed a significant elevation in Beclin-1 and LC3-II expressions when compared to EST group. Furthermore, the nano formula of FA (FA-NS) with DOX group showed a significant increase in Beclin-1 expression only when compared to all other groups (Figures 5B, C).

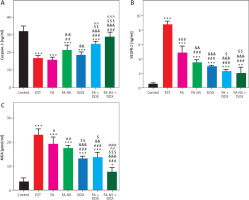

Effect of different treatments on caspase-3, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, and malondialdehyde levels

The caspase-3 levels significantly decreased in the EST group compared to the control group. These levels significantly increased in the FA-NS-treated group compared to the FA group and EST group, whereas the combination groups FA + DOX and FA-NS + DOX showed a significant elevation in caspase-3 levels compared to the EST group and other treated groups. Moreover, the nano formula of FA (FA-NS) with DOX showed a greater increase in caspase-3 levels compared to all other groups. This increase made a nonsignificant difference in caspase-3 levels between the FA-NS + DOX group and the control group (Figure 6A).

Figure 6

Serum levels of caspase-3, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2_, and malondialdehyde (MDA). Effect of treatment on caspase-3 levels in all studied groups (A), effect of treatment on VEGFR-2 levels in all studied groups (B), effect of treatment on MDA levels in all studied groups (C) DOX – doxorubicin, EST – Ehrlich solid tumour, FA – ferulic acid, FA-NS – nanosuspension of ferulic acid, MDA – malondialdehyde, VEGFR-2 – vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5). Data were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test at p < 0.05. *, #, &, $, ^, and @ indicate significant change from control, EST, FA, FA-NS, DOX, and FA + DOX, respectively (* or # represent p < 0.05, ** represent p < 0.01, ***or ### or &&& or $$$ or ^^^ or @@@ represent p < 0.001

On the other hand, the EST group showed a significant increase in VEGFR-2 and MDA levels compared to the control group. All the treatment groups, including FA, FA-NS, and DOX, as well as the combination groups, showed a significant reduction in VEGFR-2 and MDA levels compared to the EST group, whereas the combination groups FA + DOX and FA-NS + DOX showed the most significant reduction in VEGFR-2 and MDA levels compared to the EST group. Furthermore, the nano formula of FA (FA-NS) with DOX group showed a significant reduction in MDA levels compared to all other groups (Figures 6B, C).

Effect of different treatments of on total antioxidant capacity, troponin-1, and creatine kinase-MB levels

The total antioxidant capacity levels significantly decreased in the EST group compared to the control group, whereas the combination groups FA + DOX and FA-NS + DOX showed a significant elevation in TAC levels compared to the EST group. Moreover, the combination of the nano formula of FA (FA-NS) with DOX showed the most significant increase in TAC levels compared to all other groups. This significant elevation made a nonsignificant difference in TAC levels between the FA-NS + DOX group and the control group (Figure 7A). The troponin-1 and CK-MB levels significantly increased in the EST group compared to the control group. The DOX-treated group showed the highest increase in Tn1 and CK-MB levels compared to all other groups. Moreover, the combination of FA in the normal formulation (FA) and the nano formulation (FA-NS) with DOX showed a significant decrease in Tn1 levels compared to the DOX-treated group, so the combination treatment can reduce DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. In addition, the combination groups FA + DOX and FA-NS + DOX showed a notable reduction in CK-MB levels compared to the DOX-treated group (Figures 7B, C).

Figure 7

Serum levels of total antioxidant capacity (TAC), troponin-1 (Tn1) and creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB). Effect of treatment on TAC levels in all studied groups (A), effect of treatment on Tn1 levels in all studied groups (B), effect of treatment on CK-MB levels in all studied groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5) (C) DOX – doxorubicin, EST – Ehrlich solid tumour, FA – ferulic acid, FA-NS – nanosuspension of ferulic acid, TAC – total antioxidant capacity Data were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test at p < 0.05. *, #, &, $, ^, and @ indicate significant change from control, EST, FA, FA-NS, DOX, and FA + DOX, respectively. (* or & or $ represent p < 0.05, ## or && represent p < 0.01, *** or ### or &&& or $$$ or ^^^or &&& represent p < 0.001).

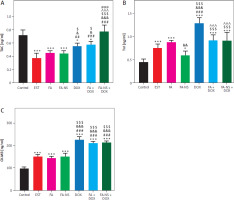

Effect of different treatments on alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase levels

The EST group showed the highest increase in ALT and AST levels compared to the control and other treated groups. However, these levels were significantly decreased in all treated groups compared to the EST group. Additionally, the combination groups FA + DOX and FA-NS + DOX showed a reduction in ALT levels compared to the DOX-treated group, with a significant reduction in the FA-NS + DOX group. Furthermore, AST levels were increased in the DOX group compared to other treated groups. The combination groups FA + DOX and FA-NS + DOX showed a significant reduction in AST levels compared to the DOX-treated group, with a more significant reduction in the FA-NS + DOX group, so the combination treatment can reduce DOX-induced hepatoxicity (Table 3).

Table 3

Levels of alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, creatinine, urea

Effect of different treatments on creatinine and urea levels

The creatinine and urea levels were significantly increased in the EST group compared to the control group. The doxorubicin-treated group showed the highest increase in creatinine and urea levels compared to the control, EST, and other treated groups. The combination groups FA + DOX and FA-NS + DOX showed a significant reduction in creatinine levels compared to the DOX-treated group, with a more significant reduction in the FA-NS + DOX group. This reduction made a non-significant difference in creatinine levels compared to the control group. Concerning urea levels, the combination of FA with DOX showed a significant reduction in urea levels compared to the DOX-treated group, so the combination treatment can reduce DOX-induced nephrotoxicity (Table 3).

Immunohistochemical findings

The expression of VEGFR-2 was estimated in the excised mammary tumour. The Ehrlich solid tumour group showed the highest expression of VEGFR-2 (Figure 8A). On the other hand, EST mice treated with FA and FA-NS revealed lower VEGFR-2 distribution than EST (Figures 8B, C). Moreover, EST mice treated with DOX, FA + DOX and FA-NS + DOX exposed the lowest VEGFR-2 distribution among all groups (Figures 8D–F). The nonparametric quantitative analysis for the area percentage of VEGFR-2 revealed a marked high expression in EST-treated mice compared to FA, FA-NS, DOX, FA + DOX, and FA-NS + DOX (Figure 8G).

Figure 8

Representative photomicrograph demonstrated immunohistochemical expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in mouse tumour from Ehrlich solid tumour (A), ferulic acid (FA) (B), nanosuspension of ferulic acid (FA-NS) (C), doxorubicin (DOX) (D), FA + DOX (E), and FA-NS + DOX (F), arrowheads indicate positive immune expression. Scale bar = 100 μm DOX – doxorubicin, EST – Ehrlich solid tumour, FA – ferulic acid, FA-NS – nanosuspension of ferulic acid Data expressed as mean ± SE, analysed using one-way ANOVA at p ≤ 0.05.

Histopathological findings

Histopathological examination of solid mammary tumour excised from EST, FA, FA-NS, DOX, FA + DOX, and NS. Ferulic acid + DOX-treated (Figures 9A–F) mice showed circumscribed nodules of poorly differentiated viable and necrotic pleomorphic neoplastic cells. The viable neoplastic cells appeared with large hyperchromatic nucleus, prominent nucleolus, anisonucleosis, and bipolar to multipolar mitotic division. The semi-quantitative scoring of necrosis in each excised tumour exhibited significant elevation of necrosis area score in all treated groups compared with the EST group (Figure 9G).

Figure 9

Effect of different treatments on histopathology of Ehrlich solid tumours excised from different experimental groups. Ehrlich solid tumour (A), ferulic acid (FA) (B), nanosuspension of ferulic acid (FA-NS) (C), doxorubicin (DOX) (D), FA + DOX (E), FA-NS + DOX (F), arrows are indicating to the neoplastic tumours and arrowheads are indicating to necrotic areas with different stages. Scale bar = 100 μm DOX – doxorubicin, EST – Ehrlich solid tumour, FA – ferulic acid, FA-NS – nanosuspension of ferulic acid Haematoxylin and eosin semiquantitative scoring of tumour necrosis. Data are expressed as mean ± SE. Data were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test at p < 0.05.

The biosafety and biocompatibility of nanohybrids were examined in the liver and kidney tissues. No tumour cells could be seen in the negative control liver and kidneys (Figures 10A, 11A). Pleomorphic, hyperchromatic, metastatic tumour cells were seen infiltrating the liver tissues of the EST group. Also, Kupffer cell activation was noticeable in all treated groups: FA, FA-NS, DOX, FA + DOX, and FA-NS + DOX; however, comparable histopathologic characterization of malignant cells was seen with various degrees of invasion, particularly for the FA-NS + FA group, which showed only a few abnormal mitotic figures of hepatocytes (Figures 10B–G). The semi-quantitative scoring of metastatic tumour in each liver exhibited significant reduction of metastatic tumour area score in all treated groups compared with the EST group (Figure 10H).

Figure 10

Representative photomicrographs for haematoxylin and eosin stained liver in mouse from negative control (A), Ehrlich solid tumour (B), ferulic acid (FA) (C), nanosuspension of ferulic acid (FA-NS) (D), doxorubicin (DOX) (E), FA + DOX (F), FA-NS + DOX (G). Thick arrow: pleomorphic, hyperchromatic, metastatic tumour foci; arrowheads: invasion of sinusoids with tumour and Kupffer cells. Scale bar = 50 μm DOX – doxorubicin, EST – Ehrlich solid tumour, FA – ferulic acid, FA-NS – nanosuspension of ferulic acid Haematoxylin and eosin semiquantitative scoring of histopathological lesion score. Data expressed as Mean ± SE, analysed using one-way ANOVA at p ≤ 0.05.

Figure 11

Representative photomicrographs for HE-stained kidney in mouse from negative control (A), Ehrlich solid tumour (B), ferulic acid (FA) (C), nanosuspension of ferulic acid (FA-NS) (D), doxorubicin (DOX) (E), FA + DOX (F), FA-NS + DOX (G), thick arrow: periglomerular and perivascular inflammatory infiltration; thin arrow: degenerated tubules. Scale bar = 50 μm DOX – doxorubicin, EST – Ehrlich solid tumour, FA – ferulic acid, FA-NS – nanosuspension of ferulic acid Haematoxylin and eosin semiquantitative scoring of histopathological lesion score. Data expressed as Mean ± SE, analysed using one-way ANOVA at p ≤ 0.05.

Metastatic tumorous invasion was not found in the kidneys of the untreated EST group; nevertheless, the kidneys exhibited severe perivascular and periglomerular aggregations of chronic inflammatory cells, primarily lymphocytes. In addition, renal tubular epithelium showed mild degenerative and necrotic alterations as well as an atrophied glomerulus (Figure 11B). However, animals given FA, FA-NS, DOX, FA + DOX and FA-NS + DOX displayed comparable histopathologic features with varying degrees of inflammatory infiltration, degenerative alterations, and necrotic changes (Figures 11C–G). The semi-quantitative scoring of lymphocytic infiltration in each kidney exhibited significant elevation of lymphocytic infiltration area score in all treated groups compared with the EST group (Figure 11H).

In the heart, the EST group showed hyalinisation and cyto-lysis of myofibers, and perivascular infiltration of mononuclear chronic inflammatory cells (Figure 12B). However, the FA and NS. Ferulic acid groups revealed moderate interfibrillar infiltration of pleomorphic mononuclear chronic inflammatory cells with extensive to moderate degeneration of cardiac myocytes (Figures 12C, D). The doxorubicin group showed myocytolysis and interfibrillar oedema with minimal interfibrillar infiltration of pleomorphic mononuclear chronic inflammatory cells’ extensive disruption and degeneration of myocardiac bundles and mononuclear inflammatory infiltration (Figure 12E). The ferulic acid + DOX group displayed moderate disruption and degeneration of myocardiac bundles and some mononuclear inflammatory infiltration (Figure 12F). The FA-NS + DOX group displayed similar cardiac architecture as seen in the negative control group (Figure 12G). The semi-quantitative scoring of lymphocytic infiltration and myocytolysis in each heart exhibited significant elevation of lymphocytic infiltration and myocytolysis area score in all treated groups compared with the EST group (Figure 12H).

Figure 12

Representative photomicrographs for HE-stained heart in mouse from negative control (A), Ehrlich solid tumour (B), ferulic acid (FA) (C), nanosuspension of ferulic acid (FA-NS) (D), doxorubicin (DOX) (E), FA + DOX (F), FA-NS + DOX (G). Thick arrow: degeneration and lysis of cardiac myocytes; thin arrow: infiltration of mononuclear chronic inflammatory cells. Scale bar = 50 μm DOX – doxorubicin, EST – Ehrlich solid tumour, FA – ferulic acid, FA-NS – nanosuspension of ferulic acid Haematoxylin and eosin semiquantitative scoring of histopathological lesion score. Data expressed as mean ± SE, analysed using one-way ANOVA at p ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in wo-men and the leading cause of cancer death among women in the world. Treatment of BC comprises surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy [43]. Doxorubicin is a first-line chemotherapeutic drug for BC treatment. However, the serious side effects of DOX limit its clinical use [44]. Natural compounds play a great role in the prevention and treatment of BC and can also reduce the side effects related to the administration of chemotherapy [45]. Previous studies reported that FA has several biological activities including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory [46], and anticancer [47].

Nano suspensions are a 2-phase dispersion containing pure crystalline drug particles dispersed in a suitable aqueous medium and stabilised by surfactants. Fundamentally, NSs have addressed the challenges of poor solubility and bioavailability associated with hydrophobic compounds [22]. The formation of nanosized particles leads to increased surface area, which in turn enhances dissolution rates and subsequently improves the drug’s bioavailability [48]. As a carrier-free particulate system, NS offers significant potential for sustained drug release, superior efficacy, reduced toxicity, and lower first-pass metabolism [48]. Given these advantages, NSs were selected as a promising nanomedicine delivery system to enhance the anticancer activity of FA. The formulation of NSs relies on the incorporation of surfactants and stabilisers, with minimal use of organic solvents. Surfactants are essential components because they reduce the interfacial tension through wetting and/or deflocculating mechanisms, which is crucial for the formulation of NSs [49]. Stabilising agents, including polymers like PVA and polysorbates (also known as Tweens or Spans), can improve the wettability of drug nanocrystals. These stabilisers create either steric hindrance or ionic barriers, which help prevent Ostwald ripening and agglomeration of NS particles. Thus, stabilisers are crucial for maintaining the homogeneity of particle size and the physical stability of NSs [22]. It is worth noting that the selected method of preparation, which involves solvent evaporation, antisolvent precipitation, and probe sonication, has eliminated the risk of residual solvent hazards in the final NS preparation.

Particle size distribution and PDI are the most important parameters in the process of nanosuspension optimisation to reflect the drug’s solubility, stability, and pharmacological activities [22, 50]. In the current study, various FA-NS were prepared using different combinations of PVA, tween-80, and SLS. The combination of SLS, tween-80, and PVA (1 : 0.5 : 0.5) in FA-NS-4 successfully produced a homogenous NS with the smallest monomodal particle size (110.23 ±4.59, PDI 0.198 ±0.004). This can be explained by the fact that the combination of polymeric stabiliser (PVA), non-ionic surfactant (tween-80), and SLS provides a protective coating for the surface of the particles, which plays a dual role: preventing crystal growth and reducing particle size. Both electrostatic and steric mechanisms contributed to this effect [48]. Furthermore, increasing the FA concentration 3–10 mg/ml did not significantly increase the particle size in FA-NS 5, which was therefore selected as the optimum formulation with higher drug loading.

The zeta potential value offers an estimate of the electric double layer surrounding the charged particles [51, 52]. The electric charge that develops on the particle surface initiates electrostatic repulsion between the nanoparticles hindering their aggregation and precipitation. Therefore, zeta potential is one of the most important factors influencing nanocarriers stability, entrapment efficiency and interactions with the biological system in vivo [53–55]. It is worth mentioning that when electrostatic stabilisation is combined with steric stabilisation (using appropriate polymers), a zeta potential of 20 mV could be sufficient to prevent the aggregation and precipitation of drug particles [22, 56]. Consequently, the obtained zeta potential of FA-NS was deemed satisfactory.

NSs offer a greater loading capacity compared to polymer- and lipid-based nanocarriers due to their carrier-free nature and high mass per volume ratios. Additionally, NSs keep drug particles in a favourable nanosized crystalline state, which enhances solubility and overcomes delivery issues without the need for actual dissolution [48]. As a result, the prepared FA-NS 5 achieved a high drug loading of 95.27% ±6.47, in line with these advantages.

The stability of nano formulations ensures their safety and effectiveness. In the context of drug delivery, the stability of NSs is a crucial factor [22]. The FA-NS 5 maintained its particle size distribution and PDI values consistently over a 2-month storage period at 2–8°C without a significant difference from fresh formulations. It also retained its negative zeta potential at –60.30 ±1.74 mV and its DCH% at 92.49% ±5.35, indicating long-term stability. This could be attributed to the solid dense state of the formulated NS that enhanced resistance to oxidation and hydrolysis, improving physical stability against settling. The combination of polymeric, ionic, and neutral stabilisers in the developed NS minimised self-repulsion of charged surfactant molecules, leading to greater surface coverage and closer packing, providing synergetic protection [48]. Overall, FA-NS 5 shows promise for further in vivo studies.

In our study, we studied the antitumour activity of FA alone and in combination with DOX. Also, we investigated the ability of FA to reduce DOX-induced different toxicities. Moreover, we compared the effects of FA-NS with FA alone and in combination with DOX. According to our study, EST-bearing mouse groups treated with FA (p < 0.01) showed a significant reduction in tumour weight compared to the EST group, reflecting its antitumour activity [57]. Also, the DOX-treated group (p < 0.001) demonstrated a significant reduction in tumour weight compared to the EST group confirming its antitumour activity [58]. The combination groups (p < 0.001) showed a more significant reduction in tumour weight, indicating the ability of FA to potentiate the antitumour activity of DOX. Additionally, groups treated with FA-NS and FA-NS + DOX showed a notable reduction in tumour weight compared to the FA and FA + DOX groups, indicating the capacity of FA nano formulation to promote the pharmacological effects [59]. In our study, we studied the antitumour mechanisms of FA, including inhibition of proliferation and angiogenesis, induction of autophagy, apoptosis, and reduction of oxidative stress.

The PI3K/AKT signalling pathway that regulates cell growth, proliferation, and survival is considered one of the most important pathways that is hyperactivated in many types of cancer, so it can be used as a target for anticancer drugs [60]. PI3K/AKT pathway inhibition by FA treatment is mediated by induction of G0/G1 phase arrest and cell death through the downregulation of expression of cyclin-dependent kinases such as CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6, which are cell-cycle-related proteins involved in cell cycle progression and hyperactivated in many cancers [61], or by the upregulation of expression of tumour suppressor proteins, such as p53 and p21, leading to cell proliferation inhibition [62]. According to our results, treatment with FA (p < 0.001) and FA-NS (P<0.001) significantly decreased AKT levels compared to the EST group, with the best impact for the combination treated groups, especially the FA-NS + DOX (p < 0.001) group. This was in agreement with a previous study that reported that FA inhibited the proliferation of HeLa and Caski human cervical carcinoma cells by downregulation of AKT expression levels through blockade of the PI3K/AKT pathway [63].

Regarding autophagy, it is a natural degradation mechanism for the clearance of damaged intracellular components in response to several types of stress such as nutrient deficiency and oxidative stress to keep cellular homeostasis [64]. Autophagy induction stimulates the autophagy mediators such as Beclin-1 and LC3-II. Beclin-1 is needed for phagophore formation and LC3-II for phagophore elongation, resulting in the formation of autophagosomes in which the cytoplasmic components are engulfed and fused with lysosome to form autolysosomes, which become ready for degradation leading to tumour suppression [65]. Our results presented that the levels of Beclin-1 and LC3-II were increased in mono-treated groups compared to the EST group. Whereas the combination of FA and FA-NS with DOX (p < 0.001) showed a significant increase in Beclin-1 and LC3-II levels. In agreement with our study, a previous study reported that FA can induce autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by increasing the levels of autophagy biomarkers including Beclin-1 and LC3-II [66].

Apoptosis is a programmed cell death that keeps balance between cell growth and cell death. Any defect occurring in this balance causes abnormal cell growth, leading to the occurrence of cancers [67]. The apoptosis induction is mediated by the upregulation of apoptotic proteins and downregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins. Ferulic acid upregulates the expression of the tumour suppressor gene p53, which activates the pro-apoptotic BAX and downregulates expression of the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 [68]. Therefore, the elevated BAX levels along with activated caspase-3 and decreased Bcl-2 levels after FA treatment lead to induction of apoptosis and cell death [69].According to our results, FA-NS (p < 0.01) alone showed a significant increase in caspase-3 levels compared to the FA group and EST group, with the most significant elevation in the combination groups (p < 0.001) compared to the EST group, especially the FA-NS + DOX group, which showed a non-significant difference compared to the control group. Furthermore, the FA-NS and FA-NS + DOX groups demonstrated a notable increase in caspase-3 levels compared to the FA and FA + DOX groups. In agreement with our study, a previous study determined that FA can promote apoptosis through caspase-3 upregulation in human prostate cancer cell line [70].

On the other hand, angiogenesis is the process by which the malignant cells receive their oxygen and nutrient requirements from the newly created blood vessels to survive and proliferate. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 is one of the most important growth factors that regulates angiogenesis. Therefore, angiogenesis inhibition by downregulation of VEGFR-2 leads to tumour suppression [71]. Regarding our results, groups treated with FA and FA-NS (p < 0.001) significantly decreased VEGFR-2 levels compared to the EST group, whereas the most significant reduction was seen in the combination groups (p < 0.001). Moreover, the FA-NS and FA-NS + DOX groups showed a greater reduction in VEGFR-2 levels than the FA and FA + DOX groups. These results were further confirmed by immunohistochemical expression of VEGFR-2. Furthermore, our results were confirmed by a previous study that reported that FA inhibited angiogenesis in the chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane model through the downregulation of VEGFR-2 expression [72].

Oxidative stress is an excessive production of ROS. The imbalance between ROS and antioxidants leads to carcinogenesis [73]. This was confirmed in our study by the increase in MDA level in the EST group, which is a biomarker of lipid peroxidation [74], whereas the TAC level was decreased in the EST group, reflecting the failure in the antioxidant defence mechanism. On the other hand, the administration of FA (p < 0.05) and FA-NS (p < 0.01) alone and in combination with DOX (p < 0.001) significantly decreased MDA levels, with the greatest impact in the FA-NS + DOX group. Total antioxidant capacity levels significantly increased in the combination groups (p < 0.001) compared to the EST group, with the greatest impact in the FA-NS + DOX group, which showed a non-significant difference compared to the control group. Moreover, the FA-NS + DOX (p < 0.001) group significantly decreased MDA and significantly increased TAC levels compared to FA + DOX, leading to a reduction in oxidative stress levels and an elevation in the TAC in EST-treated mice to maintain the balance between ROS and antioxidants. Our results agreed with a previous study that reported that FA decreases oxidative stress in formaldehyde-induced hepatotoxicity [75].

Doxorubicin is an effective anticancer drug in various types of cancers, but its clinical use is limited because it causes different organ toxicities including cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity [76].

During DOX therapy, there is an overproduction of ROS that made the myocardium under oxidative stress, leading to cardiomyopathy [77]. In our study, DOX-induced cardiotoxicity was indicated by the significant elevation of Tn1 and CK-MB levels in the DOX (p < 0.001)-treated group compared to the control group. The combination of FA and FA-NS with DOX (p < 0.001) significantly decreased Tn1 level and reduced the CK-MB level compared to the DOX group. Our results were confirmed by the study that reported that the efficacy of FA and its nano formulation in reducing cardiotoxicity in isoproterenol induced myocardial injury in rats by decreasing Tn1 and CK-MB levels [78]. Histopathological effects of DOX on the heart, including lysis of cardiac myocytes and infiltration of mononuclear chronic inflammatory cells, were significantly reversed in combination groups compared to the DOX-treated group [79]. These results reflect the cardioprotective effect of FA against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

The toxic effect of DOX on liver occurs mainly by oxidative stress that leads to hepatocytes damage, resulting in leakage of liver enzymes such as ALT and AST [80]. In our study, the combination of FA-NS with DOX (p < 0.01) significantly reduced the elevated levels of ALT compared to the DOX group. Furthermore, the combination groups FA + DOX (p < 0.01) and FA-NS + DOX (p < 0.001) significantly decreased AST levels compared to the DOX-treated group. These results were confirmed by a study that suggested the hepatoprotective effect of FA against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in rats [81]. Additionally, hepatic tissue showed pleomorphic, hyperchromatic, metastatic tumour cells and Kupffer cell activation, but these histopathological findings were significantly reduced by the administration of FA and FA-NS with DOX compared to the DOX-treated group.

Doxorubicin-induced nephrotoxicity is mainly caused by excessive ROS production that induces apoptosis in the kidney, leading to increased glomerular capillary permeability and glomerular atrophy, elevating the levels of urea and creatinine [82]. In our study, the combination of FA with DOX significantly reduced the high levels of urea (p < 0.001) and creatinine (p < 0.01) compared to the DOX-treated group, with a more significant reduction of creatinine levels only in the FA-NS + DOX group (p < 0.001) when compared to the DOX group. Our findings were confirmed by a previous study that approved the nephroprotective effect of FA in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats [83]. Furthermore, these results were confirmed by histopathological investigation of kidney tissue that showed significant reduction in inflammatory infiltration and degenerative alterations.

Although the study emphasises the potential of FA-NS in reducing the toxicities of DOX, there are several key challenges for the clinical translation of nanosuspensions:

Scalability and manufacturing: while nanosuspensions have shown promising results in preclinical studies, scaling up the production to meet clinical demands poses significant challenges. Issues such as maintaining uniform particle size distribution and ensuring batch-to-batch consistency are critical for clinical application [84].

Stability and shelf-life: strategies to maintain stability, such as the use of stabilisers and optimised storage conditions, and the need for extensive stability testing during the development phase are critical [85, 86].

Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution: The unique properties of nanosuspensions can alter the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of their payload. Thus, the importance of conducting detailed pharmacokinetic studies to understand these changes and to ensure that the therapeutic benefits are not offset by unintended side effects cannot be neglected [84].

Regulatory and safety considerations: The translation of nanosuspensions into clinical practice requires rigorous regulatory approval [87, 88].

There is a serious need for comprehensive preclinical and clinical studies to meet the safety and efficacy standards set by regulatory agencies. Additionally, potential challenges in obtaining regulatory approval due to the no-velty of the technology should be addressed.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated the antitumour activity of FA in an EST model. Ferulic acid exerts its antitumour activity by inhibition of angiogenesis and proliferation and induction of autophagy and apoptosis. Interestingly, co-administration of FA with DOX potentiated the antitumour activity of DOX but also reduced DOX-induced cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity; especially FA nanosuspension showed more significant results.