Introduction

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disease in which the body either does not produce insulin or does not fully use it. As a result, it cannot properly absorb carbohydrates, and to a lesser extent proteins and fats. This disease is classified as a civilization disease for a reason. The number of people with diabetes in the world has increased from 108 million in 1980 to 422 million in 2014 and is increasing every year. Considering the upward trend in the incidence of diabetes, experts estimated that in 2035 this disease will affect 8.8% of the population, i.e. as many as 591.9 million people [1].

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a disease that has an autoimmune etiology, which leads to the destruction of the β-cells located in the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas [2]. According to the International Diabetes Federation 2022 report, it is estimated that there are 8.75 million patients with T1DM worldwide. It is estimated that the number of patients with this disease will double by 2040 [3]. The incidence of T1DM is increasing at a rate of 2.7% to 4.4% per year depending on the ethnic group [4]. The global analyses include data on children patients up to 14 years of age. In Poland, pediatric diabetologists treat people up to 18 years of age, which is why we have included these children in the analysis. Due to the constant and accelerating increase in incidence, we have performed epidemiological studies for more than 30 years in our macroregion [5–7]. Analysis of the incidence and prevalence rates of T1DM in children in Poland, changing over several years of observation, allows us to assess the scale of the problem, provides information to improve prevention programs, predicting the needs in medical care and the effectiveness of treatment [8].

There is a link between viral infections and the development of T1DM, such as enterovirus infections [9]. Since there is a potential role of respiratory infections in developing these conditions there might also be a possible effect between SARS-CoV-2 and a higher risk of creating autoimmune reactions against β-cells [10–12]. The aim of the study was to evaluate the incidence of T1DM in children and adolescents in northeastern Poland (Podlaskie Voivodeship) in 2010–2022 and to analyze the incidence rates according to study year, age, and sex. We also aimed to speculate about the possible influence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and methods

This retrospective study covered the period from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2022. All new cases of T1DM in children aged 0–18 years in Podlaskie Voivodeship were registered. The study included 777 patients (369 girls and 408 boys). Diabetes diagnosis was established, based on ISPAD criteria [13]. The day of first insulin administration was taken as the day of onset. Data on the population size were taken from the Demographic Yearbooks of the Central Statistical Office (GUS) from 2010–2022 [14]. The data were standardized with a 2010 population of Poland as a standard population. Then we have analyzed the data dividing the studied population into 4 age groups: 0–4 years old, 5–9 years old, 10–14 years old, 15–18 years old. We have also analyzed the differences between the sex groups, different months of diagnosis and years of the analysis. Analyzes were performed using JASP, RStudio and MS Excel software. We have calculated the incidence rate as the number of newly diagnosed cases of autoimmune diabetes during the year per hundred thousand age-matched population. The differences between the age and sex groups were calculated using χ2 test. The trend of the incidence was shown using linear regression. We have also performed Poisson regression analysis to analyze the trend of diabetes incidence over time. The data were fitted with a Poisson regression model, which included the number of diabetes cases as the dependent variable and year and month as independent variables. The Poisson regression was chosen due to the count nature of the dependent variable and the relatively low mean values of cases in the individual months. Data for analysis were obtained from electronic medical documentation of University Childrens’ Clinical Hospital, the Medical University of Bialystok, Poland.

Results

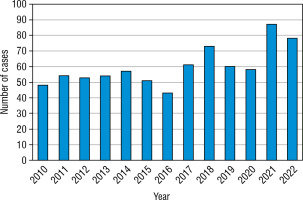

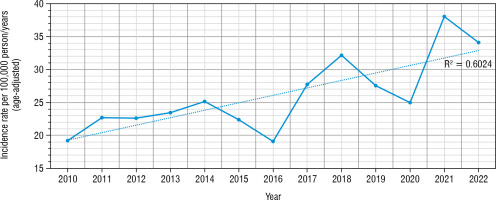

The study included 408 boys and 369 girls (52.51% vs. 47.49%). We have found that T1DM incidence rate increased nearly 1.8-fold during the study (increase in total age-standardized incidence rate from 19.48 up to 36.68/100,000 person/years, R2 = 0.6, slope = 1.138, t-test statistic: 2.78, p = 0.001; Fig. 1).

Figure 1

The incidence of T1DM in patients diagnosed in the years 2010–2022 was calculated per 100,000 person/year (age-adjusted)

The blue line indicates the incidence rate during the analyzed years adjusted to age; The dotted line indicates the linear regression graph.

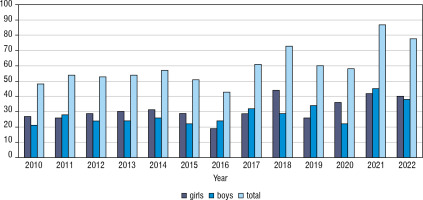

The Poisson regression analysis revealed a statistically significant positive trend in the number of diabetes cases over the years. The coefficient for the year was 0.039240 (SE = 0.009651, z = 4.066, p < 0.001), indicating that each additional year is associated with an approximate 3.95% increase in the number of diabetes cases (Fig. 2).

Figure 2

Annual diabetes cases with a fitted Poisson regression line, highlighting the trend over the years

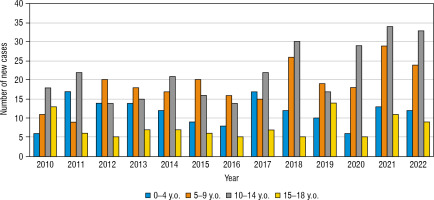

During the studied period we have found a drop in the IR in years 2019 and 2020 (IR = 27.56/100,000 and 24.97/100,000 accordingly), with a peak of incidence in 2021 (38.05/100,000 person/years). The highest number of new cases have been found in 10–14 years old age group, and the lowest – in 15–18 years old (Fig. 3).

Figure 3

The number of newly diagnosed T1DM cases in the analyzed period in different age groups

The age group from 0 to 4 years old is marked in blue. The age group from 5 to 9 years is marked in orange. The age group from 10 to 14 years is marked in grey. The age group from 15 to 18 years is marked in yellow.

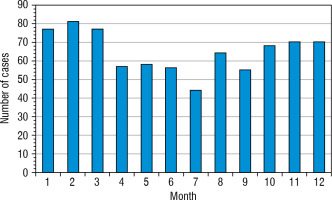

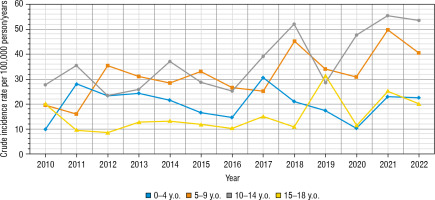

The greatest increase has been found in the youngest age group, nearly 2.3-fold (0–4 years old – from 9.86/100,000 person/year in 2010 up to 22.56/100,000 person-year in 2022). In the second age group (5–9 years old) it was 19.61/100,000 person-years in 2010 up to 40.58/100,000 in 2022, in the group 10–14 years old increase from 27.72/100,000 to 55.36/100,000 person-years, and in the group 15–18 from 20.16/100,000 in 2010 to 20.17 in 2022 (hardly any difference) (Fig. 4). Overall, the highest number of cases was found in 2021 – 87 cases, and the lowest in 2016 – 43 new cases (Fig. 5). Despite differences in IR between age groups, none were statistically significant (χ2 = 2.66, p = 0.447). We have also not found any significant difference between the number of males and females (Fig. 6). We have observed the seasonality of the new T1DM cases, with the peak of the incidence from October to March and the low from April to September. The lowest number of new cases was diagnosed in July, whereas the highest – in February (Fig. 7).

Figure 4

The crude incidence rates of T1DM in different age groups in years 2010–2022

The age group from 0 to 4 years old is marked in blue. The age group from 5 to 9 years is marked in orange. The age group from 10 to 14 years is marked in grey. The age group from 15 to 18 years is marked in yellow.

Discussion

In our study, including a period of last 13-years, we’ve shown that the incidence rate of type diabetes mellitus has increased, after analyzing almost 800 children. This is one of the first analyses of T1DM incidence rates after COVID-19 pandemic, and to the best of our knowledge – first in Poland, describing Polish population. The increasing trend is visible all over the world. One of the latest meta-analyses states that the mean incidence of T1DM is 15 per 100,000 people which is quite alarming [15]. The continent with the highest mean Incidence was America (20/100,000 people), whereas the lowest – Africa (8/100,000). In our region – Podlaskie Voivodeship – epidemiological data has been collected over the years. In the period 1988–1999, it was observed an increase in the incidence rate of diabetes from 4.6 in 1988 to 10.1 in 1999 [16]. In 2000–2004 it was 15.1 cases per 100,000 age-matched population [6]. In 2005–2012 a further increase in incidence was observed from 15.23/100,000 of the age-matched population to 20.84/100 thousand in 2012 [6]. Considering the previously mentioned sources and our data, we can conclude that the incidence of T1DM is increasing globally, especially in the pediatric population.

As for individual countries, the highest incidence rate can still be observed in Scandinavian countries like Norway, Sweden, and Finland, exceeding 60 cases/100,000 people per year [17, 18]. Also in Sardinia (Italy) the IR is really high, reaching 45 cases/100,000 person-years [19]. Podlasie region, with its IR of 38/100,000 person-years in recent years, seems to also fall into the category of high-risk regions for T1DM.

Referring to the predictions of Jarosz-Chobot et al. from 2011, up to 2025 the number of new cases in Poland would reach 46,600, with an evident downward shift in the age of onset [5]. On the other hand, there are publications from Finland, Norway, Sweden, Sardinia and the Czech Republic suggesting that T1DM can reach the plateau phase at a certain level of incidence [19–23]. Such a scenario was also expected for Poland, but so far we are observing the upward incidence trend among Polish children [24, 25]. Similarly, we can observe the increasing trend in Finland, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas in Sweden, the incidence rate seems to have reached the plateau and is now fluctuating with ups and downs through the recent years [17, 18].

According to the Central Statistical Office data and previous studies, in Poland and the world, the age group 5–9 years old used to be ranked first in terms of the number of new cases of diabetes [14, 26]. However, one of the latest worldwide studies shows that the 10–14 year-old group took the lead in terms of the number of new cases and the incidence rate [27]. In our region, the 10–14-year-old group also records the highest number of T1DM cases, which seems to be because this age group predominates in Podlasie in children. Similar results are presented by publications from several countries, including Iran, Bosnia and Herzegovina, England, and the global epidemiological meta-analyses [27–31]. Also, after calculation per 100,000 people in this age group in our region, the incidence rate remains high, especially in the last two years of our study. Therefore, it must be elaborated why this age group shows such high incidence rates despite much lower exposure to infections than younger children at preschool and school age.

Also, a worth-mentioning fact is that the highest increase in incidence (2.3-fold during the studied period) we have found in children aged 0–4 years old. We could speculate that it can be caused by pretty low exposure to infection – as toddlers before school age they are not exposed to infections in school or kindergarten. It supports the hygiene hypothesis, which indicates that advancements in hygiene and living standards have reduced the occurrence of childhood infections. This has resulted in alterations to the developing immune system, potentially elevating the susceptibility to autoimmune conditions like T1DM [32].

T1DM etiology is considered multifactorial with the strong contribution of the MHC on chromosome 6 [33]. In recent years, there has been increasing support for the theory that environmental factors, such as dietary patterns, the composition of the intestinal microbiome, exposure to toxins, and, notably, infections, play a significant role in triggering islet autoimmunity [34, 35]. The theory suggests that insufficient early exposure to a diverse range of environmental microbes and an imbalance in the gut microbiota ecosystem may contribute to the breakdown of immune tolerance, thereby increasing the risk of developing T1DM [36]. A link between infections and T1DM onset is worth mentioning. The strongest virus candidates are enteroviruses [37], but also coronaviruses like SARS-CoV2, which remain a matter of much ongoing research [11, 38].

As for the COVID-19 pandemic, its impact on the incidence rates up to date is difficult to evaluate precisely and remains the subject of various studies. For example, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the highest number of cases occurred in 2020 (the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic), while in Podlaskie Voivodeship and Upper Silesia the highest number of cases among children occurred in 2021. In 2020, we had a decline in the incidence [31]. In both studies, an incidence decline was recorded after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar situation occurred in some Italian regions [39].

In one of the recent meta-analyses performed by D’Souza et al. it has been revealed a higher incidence rate in the initial year of the pandemic compared to the period before the pandemic (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.14) Furthermore, there was a notable increase in diabetes incidence during months 13 to 24 of the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period. Also the diabetic ketoacidosis incidence was higher during the pandemic than before [40].

The increase in childhood T1DM during the COVID-19 pandemic can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, studies utilizing extensive health service datasets have proposed a potential direct impact of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) on T1DM development [41]. Secondly, there’s a possibility that the rise in childhood T1DM is linked to autoimmunity rather than direct cytotoxic destruction of beta cells in children. Recent findings from Finland indicated an elevated incidence rate ratio during the initial 18 months of the pandemic, yet only a small percentage of newly diagnosed children tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies [17]. Additionally, a study involving a large cohort of children and adolescents from Colorado, US, and Bavaria, Germany, found no significant connection between SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and the development of T1DM-associated autoantibodies [42].

But regardless of the exact cause, the increase in the incidence of T1DM and DKA remains alarming, also in the Polish population [43]. Therefore, it is even more important to develop research towards early detection, prevention, and inhibition of the progression of diabetes to the symptomatic phase. There are many attempts to achieve this.

In terms of prevention, more and more large-scale screening programs are being developed for preschool and school-age children. Since the vast majority of patients with multiple autoantibodies progress to Stage 3 of T1DM, it is now officially recommended by 2022 ISPAD consensus guidelines to perform targeted screening for autoantibodies in susceptible individuals to reduce the DKA risk and refer suitable candidates to trials and drug programs aimed at delaying or preventing ongoing beta cell loss [44].

A screening program of this kind was started in April 2023 and it is being currently performed in our center using 3 Screen ELISA test method [45]. Right now, we have more than 3 thousand school and preschool children from Podlasie screened for T1DM with positive test results in 3,65% of them (data in publication).

Also worth emphasizing are trials with orally administered insulin and probiotics aimed at inhibiting immunization against insulin molecules and the registration of teplizumab as a disease-modifying therapy to preserve β-cell function [46–48].

Limitations of the study

The study has limitations due to its single-center nature, which restricts the generalizability of its findings. However, its extensive duration of 13 years enhances the reliability of its conclusions, offering a genuine evaluation of the persistent upward trend in the incidence rates of T1DM in the childhood population.

Conclusions

The incidence of type 1 diabetes continues its rising trend in children aged 0–18 years old in Podlaskie Voivodeship in Poland from 19.48 in 2010 up to 36.68/100,000 person/years in 2022.

Various factors may influence this, but the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is worth considering.

The greatest increase is observed in the youngest age group, 0–4 years (nearly 2.3-fold during the study period). The highest number of cases and mean incidence have been shown in the 10–14-year-old age group.

Researchers and clinicians should focus on developing and promoting methods of preventing the development of diabetes to slow down the alarming trend of increasing incidence of T1DM.

POLSKI

POLSKI