Summary

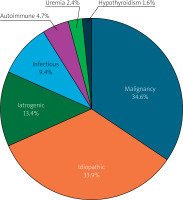

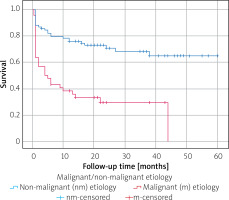

This single-center retrospective study evaluated the etiologies, fluid characteristics, and outcomes of 127 patients who underwent fluoroscopy-guided subxiphoid pericardiocentesis between 2019 and 2024. The most common causes of pericardial effusion were malignancy (34.6%) and idiopathic origins (33.9%). In-hospital and total mortality rates were 21.3% and 44.1%, respectively. Malignant etiology, pericardial tamponade, and low serum albumin were independent predictors of mortality. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed significantly worse survival in malignant effusions. The findings highlight the importance of identifying underlying causes–particularly malignancy–for prognosis and clinical management.

Introduction

The pericardium encompasses the heart and the proximal segments of the great vessels and stabilizes the heart’s position within the mediastinum. The pericardium comprises two delicate layers: a serous visceral layer and a fibrous parietal layer, typically containing 15–35 ml of serous fluid [1]. Pericardial effusion (PE) refers to an abnormal volume of fluid in the pericardial space. Any condition that induces inflammation, injury of the pericardium, or impaired pericardial lymphatic drainage causes PE [2].

Clinical manifestations of PE vary widely, ranging from asymptomatic cases to life-threatening conditions, primarily influenced by the rate of fluid accumulation and the underlying etiology [3]. Pericardial effusion can result from various malignant or non-malignant causes. Malignant PE is associated with poor survival outcomes [4]. Commonly recognized non-malignant causes include infection, autoimmune disease, pericardial injury (post-myocardial infarction, post-pericardiotomy, post-traumatic, iatrogenic), metabolic conditions (e.g., hypothyroidism and uremia) and radiation [5, 6]. In developed countries, idiopathic pericarditis, often considered to have a post-viral origin, is the leading cause of PE, whereas tuberculosis accounts for more than 70% of cases in developing countries [7].

Pericardial tamponade (PT), a severe manifestation of PE, results from increased pericardial pressure that compromises cardiac output and venous return. This condition represents a medical emergency, requiring rapid diagnosis and intervention to prevent morbidity and mortality. Patients with PT and hemodynamically unstable PE undergo pericardiocentesis (PC) to reduce pericardial pressure and alleviate associated symptoms [8].

Pericardiocentesis is performed for diagnostic purposes, particularly in cases of suspected malignancy or bacterial PE [9]. Diagnostic PC is also recommended for symptomatic moderate to large effusions that do not respond to conventional anti-inflammatory therapy. The etiology of PE can be determined by examining the biochemical, microbiological, and cytological characteristics of the fluid [10]. Pericardiocentesis is widely regarded as a safe and crucial intervention involving the percutaneous aspiration of fluid from the pericardial sac in different clinical settings [11, 12].

Despite its importance, comprehensive contemporary data on PC outcomes, etiologies, and prognostic indicators remain limited. A deeper understanding of these factors is crucial for informing risk stratification and patient management.

Aim

The aim of this retrospective study was to evaluate the etiologies, pericardial fluid characteristics, and both in-hospital and total mortality rates in patients who underwent PC. Additionally, we sought to identify factors associated with total mortality following the procedure.

Material and methods

We conducted a single-center retrospective study that included patients who underwent PC performed with the fluoroscopy-guided subxiphoid approach in the catheterization laboratory in our center between November 2019 and November 2024. Data were obtained retrospectively from the catheterization laboratory registry and hospital electronic records. The patients were classified into two groups: survivors and non-survivors. Patients with missing data for analysis were excluded from this study.

Pericardiocentesis procedure

All pericardial drainage was performed with a sheath and pigtail catheter via a subxiphoid approach in the catheterization laboratory. The puncture site (1 mm left of the costo-xiphoid angle) was anesthetized by lidocaine (1–2%). An 18G puncture needle was inserted between the xiphoid and left costal margin and advanced subcostally, directed towards the left shoulder with continuous suction applied to a 10 cc syringe, and the needle was advanced slowly towards the left shoulder while negative pressure was applied to the syringe until the fluid was visualized. When the fluid was seen, the guide wire was inserted. After confirming the position of the guide wire with the fluoroscopy, a small incision was made at the entry site, followed by the insertion of a sheathed dilator (6 Fr to 8 Fr) over the guide wire. After the dilator was removed, a pigtail catheter was inserted directly into the sheath. The pericardial fluid was aspirated using syringe suction until minimal fluid remained. The sheath and pigtail catheter were kept with underwater drainage systems until the drained fluid was less than 100 ml/day.

Patient and pericardial effusion analysis

All pericardial fluid samples were submitted for biochemical tests to determine glucose and protein levels, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, cytological examination, and microbiological culture, as recommended in the guideline [9]. Patient demographic features, comorbidities, laboratory findings, echocardiographic PE size – mild (10 mm), moderate (10–20 mm) or large (20 mm) – the hemodynamic impact of PE (presence or absence of PT), etiologies, pericardial fluid appearance (hemorrhagic/serous), and composition (exudate/transudate) were noted from hospital records.

Definitions

Pericardial fluid size in this study was defined as the largest pericardial fluid at the anterior to the right ventricle in parasternal and subcostal echocardiographic views at the end-diastolic phase of the cardiac cycle. Pericardial tamponade was defined as PE, leading to impaired cardiac filling and hemodynamic instability. A key sign of PT in echocardiography was considered right ventricular diastolic collapse [8]. Patients with pericardial fluid containing atypical cells on cytology, those with known malignancy diagnosis, or those newly diagnosed with imaging methods showing pericardial involvement of malignancy with negative pericardial fluid cytology were diagnosed with malignant PE. Pericardial effusion occurring during invasive cardiac procedures (coronary interventions, electrophysiological study and ablation, pacemaker insertion, percutaneous valvuloplasty, etc.) was defined as iatrogenic PE [13]. Bacterial growth, including tuberculosis in pericardial fluid culture, was defined as bacterial PE. Patients with a recent history of respiratory tract infection with culture-negative PE were diagnosed with viral PE after excluding other possible etiologies. Patients with known autoimmune disease and those with polyserositis were diagnosed with autoimmune PE. Patients with PE requiring dialysis and blood urea nitrogen levels > 60 mg/dl in the absence of other identifiable causes were diagnosed with uremic PE. Patients with profound hypothyroidism (elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) > 10 mIU/l with low free T4 levels) in the absence of other causes of PE were diagnosed with hypothyroidism-associated PE. Patients who did not have a recent history of respiratory tract infection, responded to medical treatment, and in whom other possible etiologies were excluded, were diagnosed with idiopathic PE. Exudates and transudates were distinguished according to Light’s criteria (pericardial fluid was classified as an exudate if one or more of the following conditions were met: fluid protein level 3.0 g/dl, fluid protein/serum protein ratio > 0.5, fluid LDH > 200 IU/l; fluid LDH/serum LDH ratio > 0.6) [9].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), under an institutional license. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of variable distributions. Continuous variables with a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared with Student’s t-test. Continuous variables with non-normal distributions were expressed as medians [interquartile ranges, IQR (Q1–Q3)] and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages and compared using Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to designate survival curves for malignant and non-malignant etiology, and the log-rank test was used for survival comparison. Multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis using the backward elimination method was employed to evaluate the independent predictors of mortality. Parameters with a p-value ≤ 0.1 in the univariate analysis in Tables I and II were included in the multivariate logistic analysis. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 127 patients who underwent fluoroscopy-guided subxiphoid PC were included in this study. The median follow-up was 16 months. In-hospital mortality occurred in 27 (21.3%) patients, and total mortality occurred in 56 (44.1%) patients during follow-up.

One major complication, pneumopericardium (0.8%), occurred and resolved spontaneously within a few days without any intervention.

The median age of the patients was 69 years; about half of the patients were female (49.6%). The age and gender distributions were similar in both groups. Common comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation rates, and left ventricular ejection fraction values, also similar in both groups (Table I). The most common etiology was malignancy with 44 (34.6%) cases, followed by idiopathic PE with 43 (33.9%) cases, iatrogenic PE with 17 (13.4%) cases, infectious PE with 12 (9.4%) cases (8 cases of infectious PE were viral and 4 of them were bacterial), autoimmune PE with 6 (4.7%) cases, uremic PE with 3 (2.4%) cases, and hypothyroidism-associated PE with 2 (1.6%) cases (Figure 1). Lung cancer was the most common malignancy, identified in 23 (52.2%) patients, followed by leukemia and lymphoma in 7 (15.9%) patients. Among the cases of malignancy, breast cancer was observed in 4 (9%) patients, gastrointestinal tract cancer in 4 (9%) patients, genitourinary tract cancer in 4 (9%) patients, and the remaining 2 malignancies were mesothelioma. Malignant cells were detected in PE cytology of 25 of 44 (56.8%) patients with malignant etiology. Among the 17 iatrogenic PEs, 6 occurred during arrhythmia ablation, 4 during pacemaker or intracardiac defibrillator implantation, 4 during transcatheter aortic valve implantation, and 3 during percutaneous coronary intervention. As for infectious PE, of the 4 bacterial pericardial effusions, 2 cultures from pericardial fluid showed M. tuberculosis, 1 showed S. aureus, and the remaining 1 showed E. coli and Proteus mirabilis. As for pericardial fluid composition, 80.3% of PEs were exudate and 19.7% were transudate. Additionally, 70.1% of PEs were hemorrhagic, and 29.9% were serous. In the evaluation of the size of PEs, 81.1% of PEs were large, and 18.9% of PEs were moderate. 74.8% of PC were performed due to PT. The appearance of effusion (hemorrhagic vs serous) and composition of effusion (exudate vs transudate) were not different between the two groups (p = 0.174, p = 0.645, respectively) (Table I). Malignant etiology, large pericardial effusion, and presentation with PT were more common in the non-survival group (p < 0.001, p = 0.042, p = 0.004, respectively) (Table I). In the comparison of laboratory values, BUN was found to be higher in the non-survival group, whereas albumin and total protein were found to be lower in this group (p = 0.008, p < 0.001, p < 0.001 respectively). In the comparison of pericardial fluid examination, fluid albumin and fluid protein values were found to be lower in the non-survival group (p = 0.014, p = 0.001, respectively). The remaining parameters – including LDH and glucose value of serum and fluid, fluid albumin/serum albumin ratio, fluid protein/serum protein ratio, and fluid LDH/serum LDH ratio – were similar between the two groups (Table II). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, malignant etiology, presentation with PT, and low albumin levels were found to be independent predictors of mortality (p < 0.001, p = 0.007, p = 0.026, respectively) (Table III). Malignant PE had a worse prognosis according to the Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis (log-rank p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

Table I

Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and echocardiographic findings of the patients

| Parameter | Total (n = 127) | Survived (n = 71, 55.9%) | Died (n = 56, 44.1%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 69 (56–76) | 67 (54–75) | 70 (60.2–76.7) | 0.219 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 63 (49.6%) | 34 (47.9%) | 29 (51.8%) | 0.663 |

| HT, n (%) | 66 (52.0%) | 38 (53.5%) | 28 (50.0%) | 0.693 |

| DM, n (%) | 27 (21.3%) | 17 (23.9%) | 10 (17.9%) | 0.405 |

| CAD, n (%) | 25 (19.7%) | 16 (22.5%) | 9 (16.1%) | 0.363 |

| AF, n (%) | 35 (27.6%) | 16 (22.5%) | 19 (33.9%) | 0.154 |

| Appearance of effusion, n (%) | ||||

| Hemorrhagic | 89 (70.1%) | 46 (64.8%) | 43 (76.8%) | 0.174 |

| Serous | 38 (29.9%) | 25 (35.2%) | 13 (23.2%) | |

| Composition of effusion, n (%) | ||||

| Exudate | 102 (80.3%) | 56 (78.9%) | 46 (82.1%) | 0.645 |

| Transudate | 25 (19.7%) | 15 (21.1%) | 10 (17.9%) | |

| Pericardial tamponade, n (%) | 95 (74.8%) | 46 (64.8%) | 49 (87.5%) | 0.004* |

| PE size, n (%) | 0.042* | |||

| Moderate | 24 (18.9%) | 18 (25.4%) | 6 (10.7%) | |

| Large | 103 (81.1%) | 53 (74.6%) | 50 (89.3%) | |

| LVEF (%) | 60 (55–60) | 60 (55–60) | 60 (55–60) | 0.837 |

| Malignant etiology, n (%) | 44 (34.6%) | 13 (18.3%) | 31 (55.4%) | < 0.001* |

| Idiopathic etiology, n (%) | 43 (33.9%) | 26 (36.6%) | 17 (30.4%) | 0.459 |

| Iatrogenic etiology, n (%) | 17 (13.4%) | 13 (18.3%) | 4 (7.1%) | 0.113 |

Table II

Laboratory findings of patients

| Parameter | Survived (n = 71, 55.9%) | Died (n = 56, 44.1%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose [mg/dl] | 113 (95–143) | 117 (101–147) | 0.518 |

| BUN [mg/dl] | 18 (14–28) | 24.5 (17.7–39.4) | 0.008* |

| Creatinine [mg/dl] | 0.93 (0.74–1.28) | 0.91 (0.64–1.57) | 0.844 |

| Albumin [g/dl] | 3.6 ±0.6 | 3.1 ±0.5 | < 0.001* |

| Total protein [g/dl] | 6.5 (6.1–7.1) | 5.9 (5.3–6.4) | < 0.001* |

| LDH [IU/l] | 225 (168–306) | 281 (179–433) | 0.072 |

| Hemoglobin [mg/dl] | 11.3 ±1.8 | 10.9 ±2.2 | 0.315 |

| WBC [103/μl] | 9.3 (7.8–12.3) | 8.7 (5.7–13.0) | 0.558 |

| Platelet [103/μl] | 252 (191–379) | 256 (188–338) | 0.657 |

| CRP [mg/l] | 59 (12–140) | 66 (18–98) | 0.894 |

| Fluid glucose [mg/dl] | 99 (81–130) | 99 (79–123) | 0.885 |

| Fluid albumin [g/dl] | 2.9 ±0.7 | 2.5 ±0.7 | 0.014* |

| Fluid protein [g/dl] | 5.0 (4.6–5.6) | 4.3 (3.6–5.0) | 0.001* |

| Fluid LDH [IU/l] | 622 (195–1198) | 509 (215–1421) | 0.919 |

| Fluid albumin/serum albumin ratio | 0.82 ±0.16 | 0.82 ±0.20 | 0.813 |

| Fluid protein/serum protein ratio | 0.76 (0.69–0.84) | 0.74 (0.63–0.81) | 0.352 |

| Fluid LDH/serum LDH ratio | 2.39 (0.89–4.96) | 1.58 (0.83–4.78) | 0.406 |

Discussion

This study presents the results of a retrospective cohort analysis examining the characteristics and outcomes of patients who underwent PC at a single tertiary care center. This study examines the characteristics of patients and pericardial fluid, identifies predictors of mortality, and highlights the safety and efficacy of the procedure.

Pericardiocentesis is generally considered a safe and effective procedure with a low complication rate and high success rate when performed under imaging guidance. Large studies report that major complications occur in approximately 1.2% [14–17] of cases if performed with fluoroscopy or echocardiography guidance. In our study, the frequency of major complications was low, which is consistent with the existing literature. Both fluoroscopy and echocardiography are widely used imaging techniques to guide PC, and neither method is clearly safer than the other. The etiology of PE and comorbidities, rather than the choice of imaging modality, are more predictive of complications [18]. Fluoroscopy-guided PC may be preferred, especially in post-surgical patients where echocardiography may be limited by artifacts and in complex cases [17, 18].

In this study, malignant and idiopathic etiologies were found to be the most common causes of PE requiring PC, with nearly identical rates (34.6% and 33.9%, respectively), which aligns with the literature [13, 19]. The proportion of malignant PE in our cohort was slightly higher, possibly due to a more comprehensive diagnostic approach at our tertiary center.

Malignant cells were detected in 25 (56.8%) PEs with malignant etiology in our study. In a study examining cancer patients who underwent PC, this rate was determined to be 41% [20]. Malignant cells are not always detected by cytology in all malignant PEs. While cytology is a highly valuable diagnostic tool, it may be negative in some malignant patients. Low cellularity in the sample or technical limitations in sample collection may cause false negatives. Fibrinous pericarditis may conceal malignant cells, making them difficult to detect. Lymphomas are a common cause of false-negative results, as their malignant cells may be difficult to identify in fluid. Cancer involvement limited to the pericardial surface without extension into the pericardial space can also result in negative cytology despite malignancy [21, 22]. Moreover, obstruction of the lymphatic system due to cancer infiltration or radiotherapy-induced fibrosis, and fluid retention induced by specific chemotherapies (anthracyclines, dasatinib) may also cause PE in patients with malignancy [20]. Therefore, in our study, as well as patients with pericardial fluid containing malignant cells on cytology, those with known malignancy or those diagnosed with imaging methods showing pericardial involvement of malignancy with negative pericardial fluid cytology were considered to have malignant PE. In the evaluation of PE etiology, it is of great importance to use advanced imaging methods to assess the underlying malignancy as well as cytological analysis of pericardial fluid.

The prevalence of idiopathic PE is a diagnostic challenge. Although advances in diagnostic tools have improved the identification of specific etiologies, many cases remain idiopathic, particularly due to a lack of comprehensive diagnostic approaches [23]. Definitive diagnosis of viral PE is made by the direct identification of viral genomes in pericardial fluid or tissue, achieved through molecular techniques such as PCR. Several viral PEs are often categorized as idiopathic because viral detection in pericardial fluid or tissue is not routinely performed. Consequently, specific viral agents are not identified, which can create challenges in diagnosis and treatment [9, 24]. Idiopathic PE is often presumed to result from viral infections, which may trigger autoinflammatory processes. This suggests that idiopathic PE could be considered an autoinflammatory disease [25–27]. An IL-1 receptor antagonist targets the inflammatory pathways and has shown promise in treating refractory cases of recurrent pericarditis and PE [28]. This promising treatment response supports the hypothesis that virus-induced autoinflammatory processes contribute to idiopathic pericarditis and PE. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting a genetic predisposition to recurrent idiopathic pericarditis and PE. Genetic factors may contribute to the recurrence of the disease [29]. The role of viral infections and genetic factors in etiology remains an area of active investigation [29–31]. There is a need for further research to better understand the pathogenesis of idiopathic pericarditis and PE and to develop more effective treatment strategies. In our study, we hypothesized that viral PEs were detected less frequently because routine PCR was not performed to identify viruses in pericardial fluid at our center. Our findings underscore the importance of conducting a thorough diagnostic examination to identify infectious causes.

In this study, malignant etiology, presentation with PT and low albumin value were found to be independent predictors of mortality. Malignant PEs have been shown to significantly worsen survival rates compared to non-malignant causes [13, 15, 19, 32]. This is likely due to the aggressive nature of underlying cancers and the potential for metastasis, which complicates treatment and management [32]. In our study, malignancy was found to be an independent predictor of mortality, and patients with malignant PE had lower survival rates than those with non-malignant PE. These findings underscore the importance of determining the underlying causes of PE, because etiology significantly influences patient outcomes. Malignant PE, which represents a substantial proportion of patients, is associated with poorer survival rates, emphasizing the need for prompt oncologic evaluation, especially in patients with unknown etiology [20].

Similarly, our study, a tertiary center-based study, identified malignancy as the most common etiology and found it to be a significant predictor of long-term mortality [33]. In our study, presentation with PT was found to be an independent predictor of mortality. Consistent with our observations, previous studies have found that mortality is notably higher in patients with neoplastic PE and those presenting with hemodynamic instability who underwent PC [13, 15]. Its association with increased mortality may reflect the severity of the underlying disease and the hemodynamic compromise at the time of PC. Pericardiocentesis is often life-saving in PT, but the risk of multi-organ dysfunction and delayed cardiac filling recovery remains significant in patients with PT. This underscores the importance of rapid diagnosis and intervention in PT to improve patient outcomes.

In our study, low albumin values were found to be independent predictors of mortality. Similarly, in a retrospective study that included patients who underwent PC, hypoalbuminemia was identified as a predictor of mortality in patients with moderate to large PE requiring PC [34]. Serum albumin levels can predict the necessity for pericardial drainage; a low albumin level was found to be associated with a higher risk of requiring drainage in uremic PE [35]. In another study, hypoalbuminemia was associated with moderate to severe PE in patients with chronic kidney disease [36].

In our center, since bedside PC records were not available, only patients who underwent PC under fluoroscopy guidance in the catheterization laboratory were included. Minor complications were certainly observed during the procedure, but since minor complications were not recorded in the hospital registry, they could not be mentioned in our study. This study has several additional limitations, including its retrospective design, and the cohort examined was based on a single center’s experience, with a relatively small sample size. This limitation may reduce the generalizability of our results. In our center, as in many centers, routine PCR was not conducted to identify viruses in pericardial fluid. Therefore, viral PEs may be detected less frequently.

Conclusions

This single-center study provides valuable insights into the etiologies and outcomes associated with PC required for PE. Pericardiocentesis performed with a fluoroscopy-guided subxiphoid approach is considered a safe and effective procedure with a low complication rate. Understanding etiologies is crucial for the prognosis and management of PE. Malignant PE had a worse prognosis than non-malignant PE. Therefore, in addition to cytological analysis of the pericardial fluid, the use of advanced imaging methods plays a pivotal role in the evaluation of malignancy, especially in patients without a known malignancy, as PE may be the first sign of cancer.