Acute myocardial infarction (AMI), particularly ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), remains a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality, demanding sustained attention from the medical community [1]. While decades of progress have refined reperfusion strategies and systems of care, the most crucial determinant of improved patient outcomes continues to be timely treatment delivery [2]. As Giuseppe De Luca established nearly two decades ago, every minute of delay from symptom onset to reperfusion significantly increases mortality risk [3]. This observation gave birth to the now-canonical principle that “time is muscle” [4].

The devastating impact of ischemic time underscores the necessity for relentless efforts to accelerate reperfusion. Delays – whether patient-related, system-based, or logistical – can exponentially compound myocardial damage. Current clinical guidelines emphasize that the time from first medical contact to reperfusion through primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) should not exceed 120 min, with an optimal target of under 60 min for patients presenting directly to PCI-capable centers [1]. However, data from contemporary registries reveal persistent gaps in achieving these targets. For instance, analysis of the ORPKI registry in Poland demonstrated median system delays of approximately 120 min, indicating that 50% of patients receive treatment outside recommended timeframes – a sobering reminder of ongoing challenges [5]. Various initiatives, including the “Stent for Life” and “Stent – Save a Life!” programs, have demonstrated that coordinated efforts can successfully reduce treatment delays [6, 7]. Nevertheless, sustained focus and robust data collection remain crucial, particularly as these programs have faced setbacks due to external factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic [7, 8].

Minimizing delays requires a comprehensive approach addressing factors at every stage of care. Patient-related delays, often stemming from symptom misinterpretation or lack of awareness, deserve particular attention. Vulnerable populations – including women, elderly individuals, and those with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease – may experience atypical presentations that result in further delays [5, 9–11]. Public health campaigns focused on increasing awareness of early AMI symptoms and promoting prompt emergency medical services (EMS) activation are essential, especially within these high-risk demographics [1]. Emerging wearable technologies capable of monitoring heart rhythms and detecting ischemic changes show promise for facilitating rapid intervention, though their validation and widespread implementation remain crucial prerequisites for proving efficacy. These technologies may prove particularly valuable for highest-risk patients, including those experiencing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). Recent research by Goniewicz et al. [12] demonstrates that shorter EMS response times correlate with improved rates of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) in OHCA patients, emphasizing the critical importance of EMS prioritization and rapid response protocols.

System-related delays frequently arise from fragmented care pathways and workflow inefficiencies. The “hub-and-spoke” model, wherein PCI centers collaborate with non-PCI hospitals and EMS providers, offers a valuable organizational framework [1, 6]. This system requires expedited transfers to PCI centers, supported by pre-hospital electrocardiogram (ECG) transmission and early cathlab activation [1]. Within hospitals, standardized operating procedures, continuous time monitoring, and emphasis on reducing door-to-balloon time remain vital. The importance of streamlining in-hospital processes is further highlighted by recent research from Söner et al. examining emergency department delay time (EDDT) [13]. While EDDT did not predict in-hospital mortality, it demonstrated an independent association with increased one-year mortality risk. Additionally, opportunities for improvement exist even within primary PCI procedures. Recent evidence supports immediate reperfusion of the culprit vessel before completing comprehensive angiography, potentially reducing delays without compromising patient safety or clinical outcomes [14]. In addition, a new subcutaneous glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitor (Zalunfiban) has shown promising initial results and is currently being tested as a facilitation strategy in a large randomized trial [15]. This development may prove valuable in accelerating treatment for STEMI patients and reducing reperfusion delays in the coming years.

While STEMI remains the primary focus of rapid reperfusion strategies, it is crucial to recognize the limitations of relying solely on ST-segment elevation as a criterion for emergency intervention [1]. Approximately one-third of patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction have acutely occluded coronary arteries that could benefit from urgent reperfusion. The emerging concept of “occlusion MI” advocates for a more comprehensive approach that transcends traditional ECG classifications [16]. This paradigm emphasizes the importance of subtle ECG changes, including the De Winter pattern and Sgarbossa criteria, as potential indicators of vessel occlusion [16–18]. Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms show promise in identifying these nuanced changes, though such technologies require rigorous validation through additional clinical studies [16, 19].

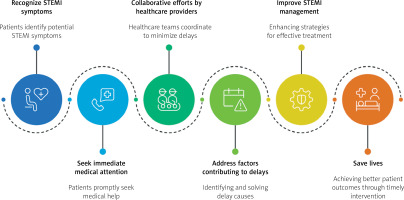

In conclusion, improving outcomes in AMI necessitates a sustained, multifaceted approach across all domains of care, with particular emphasis on minimizing treatment delays (Figure 1). Key components include enhanced public education, innovative technology implementation, and optimized clinical protocols. Patient-focused initiatives must prioritize awareness and promote rapid EMS access. Healthcare systems must continue streamlining EMS protocols, improving in-hospital efficiency, and fostering inter-facility cooperation. Novel strategies – including culprit vessel revascularization before complete angiography and AI-enhanced ECG analysis – show considerable promise but require further validation before widespread implementation. Most importantly, the fundamental message derived from decades of research remains unchanged: every minute of delay still counts!