Introduction

Infertility is a distressing concern among women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), a prevalent endocrinopathy that accounts for a substantial proportion of anovulatory infertility. Affected cases often experience a combination of factors that impair fertility, including chronic anovulation, hyperandrogenemia, a range of metabolic disturbances, including insulin resistance (IR), and obesity [1].

These interconnected metabolic and hormonal factors collectively impact ovarian function and reproductive potential. Our understanding of PCOS pathophysiology has progressed, but significant gaps remain in elucidating the metabolic mechanism behind PCOS-related infertility, making addressing PCOS infertility challenging [2].

An emerging area of research involves zinc-α2-glycoprotein (ZAG), an adipokine involved in lipolysis, insulin sensitivity and fat mobilization. Zinc-α2-glycoprotein levels were found to be reduced among obese individuals and those suffering from IR, two metabolic features prevalent among PCOS cases [3, 4].

Zinc-α2-glycoprotein is increasingly recognized for its regulatory role in metabolic haemostasis and energy balance. It plays a significant role in counteracting obesity-related metabolic dysfunction and was found to be downregulated in cases showing features of metabolic syndrome. Moreover, it showed a promising connection with body mass index (BMI), waist circumference and IR [5, 6]. Although ZAG’s role in metabolic regulation, PCOS, and type 2 diabetes was explored [7, 8], its role in reproductive dysfunction, especially infertility, remained unexplored. Given that PCOS is defined as both a reproductive and metabolic disorder [8, 9], we hypothesized that alteration in ZAG expression may contribute to the pathophysiology of infertility by influencing both adiposity and IR [6].

The current markers of fertility potential in PCOS, including the anti-Müllerian hormone and luteinizing hormone/follicle-stimulating hormone (LH/FSH) ratio, have been widely studied [10, 11]. In contrast, ZAG’s role in fertility in these populations remained unexplored.

This study is designed to examine the relationship between circulating ZAG levels and anthropometric, hormonal and metabolic parameters among PCOS women. Additionally, the study is aimed to evaluate ZAG ability to predict fertility potential among PCOS women and test its efficacy as a superior or complementary marker compared to traditional fertility predictors. Addressing this knowledge gap will improve our insight into ZAG’s clinical applications and potential diagnostic or therapeutic avenues in managing PCOS infertility.

Material and methods

Study type and setting

A comparative observational cross-sectional study was conducted in the infertility department of the Al-Yarmouk Teaching Hospital from 20 April 2023 to 1 March 2024. The study employed purposive sampling to recruit PCOS cases who agreed to participate after being informed of the study’s aim and objective. The Mustansiriyah University Ethics Committee granted ethical approval, with No. IRB 67; dated 1/2/2023. The study adheres to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration in all its procedures.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Women aged 18–35 years diagnosed with PCOS based on Rotterdam criteria 2003 [12],not aiming to get pregnant and not breastfeeding were invited to participate. No restriction was placed on body weight as the study aimed to examine ZAG impact across the full spectrum of obesity. Exclusion was made for cases with medical conditions such as diabetes, thyroid disorders, or other endocrinopathies. Cases with chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and those on chronic drugs such as steroids, aspirin, or NSAID, ovulation induction drugs, oral contraceptive pills, and smokers were all excluded.

Eligible cases (n = 120) were sub-grouped into infertile (60/120) and fertile categories (60/120) based on World Health Organization and American Society for Reproductive Medicine definitions of infertility. Women were defined (as infertile) when they failed to achieve a clinical pregnancy after one year of regular unprotected sexual intercourse. In contrast, women were considered fertile if they had conceived spontaneously within the last 1 year without fertility-enhanced medications or assisted reproductive techniques [13].

Workflow and sampling parameters

After obtaining a detailed medical history and performing a physical examination, age, body weight, height (for BMI estimation) and waist circumference were recorded for study sub-groups. All cases were scheduled for blood sampling during day 2 of the menstrual cycle, where 5 ml of venous blood was taken at 8:00–9:00 AM following overnight fasting of at least eight hours. The collected blood was sent to the following lab investigations:

FSH,

LH,

anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH),

prolactin,

total testosterone,

fasting insulin and fasting blood glucose to calculate homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR).

The above variables were measured using sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay “ECLIA”.

Serum levels of ZAG (zinc-α2-glycoprotein) were estimated via a commercially available ELISA kit (Catalogue No. BMS2205, In vitro gram; Carlsbad, California, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sample size determination

Sample size = (Z1 + Z2)2 × [p1(1 – p1) + p2(1 – p2)]/(p1 – p2)2 [14]

Sample size = (Z1 + Z2)2 × [p1(1 – p1) + p2(1 – p2)]/(p1 – p2)2

N = (1.96 + 0.84)2 × [0.55 (0.45) + 0.35 (0.65)]/(0.2)2

N = 7.84 × 0.467/0.32 = 3.665/0.032

N = 113.12 ≈ each group should have 56 cases

Z1 – the significant level set for the 1st group (α), Z2 – the desired statistical power for the 2nd group (1β); p1, p2 – the estimated proportion in the 1st and 2nd groups

Statistical analysis

The data normality was checked by the D’Agostino test. Continuous data were presented as means and standard deviations (M ±SD) and compared by Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test when appropriate. The degree of correlation between ZAG and study parameters was examined using Spearman’s rank correlation test and respective p-values. The receiver operator characteristic curve (ROC) with respective sensitivity, specificity and p-value calculated ZAG’s ability to predict infertility. A pairwise compression was made via ROC with other fertility markers. Binary logistic regression and its respective odds ratio (OR) were calculated for BMI and ZAG to assess their impact on fertility potential. A mediation analysis was conducted to explore the mediation effect of ZAG and BMI (taken as independent variables) on fertility potential; with total and proportional effect calculation. All tests were conducted by SPPS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Significance was set at p < 0.05 for all.

Results

The primary criteria of the study participants were expressed in Table 1. The age showed no statistical significance, while BMI and waist circumference were statistically higher among the infertile PCOS group compared to fertile PCOS cases. The follicle-stimulating hormone, LH, AMH, prolactin, testosterone and HOMA-IR were meaningfully/significantly high among the infertile PCOS vs. fertile PCOS cases. Zinc-α2-glycoprotein showed significantly lower levels among the infertile vs. fertile cases (37.08 ±3.885 vs. 54.25 ±14.71 µg/ml); p < 0.0001.

Table 1

The primary criteria/parameters of the study participants

In Table 2 ZAG was correlated to the study parameters; it showed an insignificant correlation to age and significant negative correlations to all other parameters. The strongest correlation was BMI, waist circumference and HOMA-IR with r = (–0.81, –0.78, –0.48), respectively.

Table 2

Zinc-α2-glycoprotein correlations with anthropometric, hormonal and metabolic study parameters

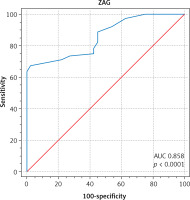

The receiver operator characteristic curve was shown, where ZAG’s ability to predict fertility potential among PCOS cases was examined. At a cut-off value of > 42 µg/ml, ZAG predicted fertility potential with 67% sensitivity and 97.50% specificity, with a reliable area under curve (AUC) of 0.858; p < 0.0001 (Fig. 1). Zinc-α2-glycoprotein performance was further compared to AMH and LH/FSH ratios in Table 3. The best fertility predictor was AMH, followed by ZAG and LH/FSH ratio, with a highly significant p-value.

Table 3

Pairwise comparison of receiver operator characteristic curves of parameters that predict fertility among polycystic ovarian syndrome receiver operator characteristic curves

| Parameters | AUC | 95% CI | Cut off value | Sensitivity | Specificity | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMH | 0.960 | 0.908–0.967 | < 9.55 | 90 | 95 | < 0.0001 |

| ZAG | 0.858 | 0.783–0.915 | > 42 µg | 67.2 | 97.5 | < 0.0001 |

| LH/FSH ratio | 0.816 | 0.735–0.881 | < 1.255 | 96.25 | 25.5 | 0.002 |

Fig. 1

At a cut-off value of > 42 μg/ml, zinc-α2-glycoprotein predicted fertility potential in polycystic ovarian syndrome ca ses with 67% sensitivity and 97.50% specificity AUC – area under curve, ZAG – zinc-α2-glycoprotein

In Table 4 binary logistic regression was done to explore the effect of BMI and ZAG (taken as an independent factor) on fertility, which was taken as the outcome. Body mass index had an OR of 0.658; p < 0.001, i.e., for every increase in BMI, the fertility odds reduce by 34.2%, keeping in mind that ZAG is constant. While ZAG had an OR of 1.088, p = 0.055, i.e., for every increase in ZAG, the fertility odds increased by 8.8% while BMI was constant.

Table 4

Binary logistic regression for body mass index and zinc-α2-glycoprotein effect on fertility

| Parameters | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 0.658 | 0.54–0.81 | < 0.001 |

| ZAG | 1.088 | 0.99–1.187 | 0.055 |

Since a significant difference in BMI was found among the infertile and fertile PCOS cases, a mediation test was used to understand if the improved fertility was due to BMI or due to other factors, i.e., ZAG.

Table 5 confirms a significant mediation. Body mass index had an indirect effect on infertility, which was mediated via ZAG with an effect size of –0.35. Additionally, BMI has a direct effect on infertility, with an effect size of –0.344.

Table 5

Mediation analysis to test the effect size of zinc-α2-glycoprotein and body mass index on infertility

| Pathways | The effect size (β) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Path (A) BMI-ZAG | –0.35 | < 0.05 |

| Path (B) ZAG-infertility | 0.115 | < 0.05 |

| Path (C) BMI-infertility | –0.344 | < 0.05 |

| Path (D) indirect effect (A × B) | –0.05 | < 0.05 |

While the total effect mediated by ZAG was –0.394; the ZAG proportion effect was 13.5%. This suggests that ZAG is a possible mediator that explains part of BMI’s inverse effect on infertility.

Discussion

The analysis showed that ZAG levels were significantly lower among infertile PCOS cases. Zinc-α2-glycoprotein levels were inversely and strongly linked to anthropometric (BMI, waist circumference) and hormonal parameters among women with PCOS. As a predictor of infertility, it had good discrimination power, yet it was proceeded by AMH.

Zinc-α2-glycoprotein and anthropometric parameters

Zinc-α2-glycoprotein levels were found to be reduced among PCOS cases compared to healthy controls. As a lipid mobilizing agent, reduced ZAG levels among high BMI and obese cases may impair lipolysis and exacerbate IR; both are core elements of PCOS pathophysiology [4].

Zinc-α2-glycoprotein was found to be correlated to anthropometric and hormonal factors among PCOS women. Our results aligned with earlier studies that confirm inverse correlations of ZAG with anthropometric parameters, as in Lai et al. [5]. Moreover, reduced ZAG levels were found to correlate with the degree of obesity, aligning with the current analysis and disturbance of metabolic and hormonal factors [4, 6].

Ceperuelo-Mallafré et al. demonstrated that ZAG prompts fat mobilization and lipolysis in the subcutaneous and visceral fat; this action was closely associated with adiponectin expression. Our finding agrees with theirs, showing a stronger association with BMI (r = –0.81) than waist circumference (r = –0.78) [15] .

Zinc-α2-glycoprotein and metabolic parameters

The analysis showed a significant correlation with HOMA-IR, in line with Wang et al. and Balaz et al., ZAG regulates body fat sensitivity to circulating insulin; if reduced, lipolysis and fat mobilization will be reduced, thus increasing obesity parameters and waist circumference [6, 16]. Zinc-α2-glycoprotein was significantly linked to HOMA-IR, in good agreement with Yang et al. and Zheng et al., who observed reduced levels of ZAG in overweight and hyperglycaemic PCOS cases [17, 18].

Qu et al. study examined the diagnostic value of the natural logarithm of ZAG to HOMA-IR (ln (ZAG/HOMA-IR)) and proved its superiority in the detection of IR even when compared to the clamp methods for detecting IR and at lower coast. Their finding confirms a strong inverse correlation between ZAG and IR with r = –0.86; p < 0.001, compared to the correlation observed in the current study resulting in r = –0.48; p = 0.001. They identified the optimum ZAG ratio cut-off at 2.92, yielding an AUC of 0.96, significantly higher than AUC of 0.80 for HOMA-IR; p < 0.01 [19, 20].

Interestingly, Zheng et al. found that ZAG levels were increased following metformin therapy, which underscores the diagnostic and prognostic value of ZAG application as a marker of therapeutic progress [17].

Zinc-α2-glycoprotein and hormonal parameters

Another study compared ZAG serum level centile with the LH/FSH ratio. They declared a low LH/FSH ratio trend in cases with low ZAG levels, which failed to reach statistical value. The discrepancy in our findings may be due to differences in sample size, analytic methods, and inclusion criteria [5].

Testosterone hormones were inversely and significantly linked to ZAG in the current study, in agreement with Tang et al.’s study with a significant p < 0.0001 and Lai et al. result, which confirms an inverse negative correlation with the free androgen index [5, 21, 22]. Zinc-α2-glycoprotein levels were linked to PCOS phenotype. According to Tang et al., ZAG was the highest in normal-androgenic cases and was linked to androgen (consistent with our study results) and PCOS phenotype [22].

The analysis confirmed that ZAG discriminated PCOS cases with 67% sensitivity and 97.50% specificity, with a reliable AUC of 0.858; p < 0.0001, which is in good agreement with Luo et al. that had an AUC of 0.83; 75% sensitivity, 80% specificity in PCOS diagnosis [23]. Anti-Müllerian hormone is a reliable predictor for assessing fertility potential among PCOS cases, especially when evaluating age-related reproductive decline; its productive value affects treatment decisions and tailors ovarian stimulation protocols [24, 25]. While LH/FSH demonstrate considerable variability among PCOS cases, and for that, they serve as a valuable complementary screening test that mirrors hormonal imbalance [26].

In the current study, ZAG was significantly correlated to both AMH LH/FSH; however, it did not surpass AMH in predictive performance, which continues to be the gold standard [27]. Combining multiple biomarkers can enhance diagnostic accuracy and improve patient care.

Zinc-α2-glycoprotein was significantly lower in the infertile group, who showed significantly higher BMI. Since ZAG was strongly and inversely linked to BMI, a regression analysis was employed to verify BMI’s impact on the results.

The analysis showed a significant effect of BMI on fertility potential compared to a trend effect of ZAG on fertility (p < 0.001 vs. p = 0.055). This can be due to a small sample size or a mediation effect [28].

Pearsey et al.’s meta-analysis noticed that ZAG levels were significantly linked to deglycation; however, that association was lost when BMI was standardized; they suggested a mediation effect of ZAG on obesity and advised more research. In the current study, the mediation test was positive, and it further supported ZAG’s potential mediatory role of BMI in fertility with a 13.5% overall effect [3].

This is understandable as ZAG serves as an adipokine that influences insulin sensitivity and lipolysis; higher BMI reduces ZAG and vice versa. Although ZAG does improve metabolic function, its role is limited compared to BMI [17, 18, 29].

The body mass index role in fertility is exerted through a direct pathway and indirect pathways (mediated by ZAG). Indeed, BMI has a significant impact on fertility, and obesity tends to inversely impact IR hormonal balance and create a state of chronic low-grade inflammation [8, 16].

Taken together, all aforementioned factors impact ovarian function and reproductive potential. Zinc-α2-glycoprotein seems to have a complementary role in PCOS fertility, mostly a mediator between BMI and fertility. Its capacity to improve insulin sensitivity and increase fatty tissue breakdown can partially mitigate the impact of high BMI. Still, ZAG is not enough to counteract obesity’s broader metabolic dysfunction [30].

Obesity aggravates various metabolic and cardiovascular risk profile among women with PCOS which was discussed by previous research [31–33] reporting elevated cardiometabolic parameters in obese cases compared to their non obese counterparts and healthy controls. The current study results reinforce the detrimental impact of obesity on fertility potential among PCOS cases and highlights the importance of early metabolic screening and weight-focused management strategy as an integral component of comprehensive care.

Study limitation

A cross-sectional study was conducted in a single-centre study with a relatively small sample size, which may limit external validity. A longitudinal design would more effectively capture the causal association between ZAG and PCOS-related outcomes. Some studies suggested a circadian variation in ZAG; this point was not addressed here. Additional data on dietary intake, physical activity, and inflammatory markers were lacking, representing a study confounder.

Study strengths

Few studies have investigated ZAG’s role in infertility, specifically among PCOS women. Unlike most works focused on metabolic outcomes, the current work presents novel evidence linking ZAG to reproductive hormones and highlights its potential role as a mediator between adiposity and hormonal imbalance.

Zinc-α2-glycoprotein unique dual association with the metabolic and hormonal aspect of PCOS syndrome, added to its modifiable levels through therapy or weight reduction, reinforces its role as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in PCOS-related infertility.

Conclusions

Zinc-α2-glycoprotein is a potential biomarker for fertility that links metabolic and reproduction dysfunction in PCOS women. It mediates 13.5% of obesity’s inverse effect on fertility. Restoring normal ZAG levels may improve fertility odds and can have prognostic value in following the therapy in those populations. Further longitudinal, larger-sized studies are recommended to explore newer diagnostic and prognostic avenues to improve reproduction potential among PCOS cases.