Introduction

Grey zone lymphoma (GZL) is a subtype of B-cell lymphoma, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), especially primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, and classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cHL). This disease is rare in childhood and adolescence. Diagnosis can be particularly difficult because it has features of both Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It may show positivity for CD20, CD30, MUM1, PAX5, CD79a, BOB1, OCT2, and BCL-6, whereas expression of CD15 is variable and may be negative in GZL [1, 2]. It often has an aggressive clinical course.

There is no standardized treatment protocols for GZL, particularly in paediatric populations because of the rarity of the disease. Moreover cHL and pPMBCL may occur simultaneously as a composite disease or sequentially, and they are typically managed with different therapeutic approaches. This absence of unified guidelines presents a challenge in clinical practice. Typically, individualized treatment strategies that take into account the distinct characteristics and therapeutic requirements of each condition are necessary [2]. In recent years, inhibition of the activity of negative immune checkpoints such as blocking the binding between programmed death 1 (PD-1) and programmed death 1 ligand (PD-L1) molecules has emerged as a promising strategy for cancer treatment. Histopathological studies in cHL show high expression of PD-1 on lymphocytes that build the tumour microenvironment. It has been reported that GZL may be more related to cHL than to primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, which may explain the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in this condition [1, 3].

Programmed death 1 regulates the immune response by binding to its PD-L1 or PD-L2, which in turn decreases T-cell activation and suppresses T-cell proliferation and cytokine production [3].

This is one of the mechanisms of the tumour escape from immune surveillance. The permanent interaction of PD-1 with PD-L1 within the lymphocytes infiltrating the tumour leads these cells to a state of exhaustion and inactivity. Recognition of tumour antigens by activated T-cells is possible by blocking PD-1 or PD-L1 [4].

Pembrolizumab is a humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody against PD-1, approved for treatment of many cancers including relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma in adults [4–6].

In this case report, we present difficulties in the diagnosis and treatment of GZL in a child and the emerging role of pembrolizumab as an effective therapy.

Case report

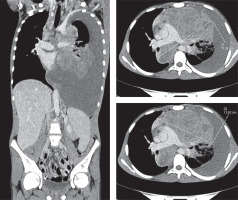

A 15.5-year-old male presented with cough, fatigue, lack of appetite, and weight loss lasting about 2 months. Computed tomography revealed a huge mediastinal tumour (105 mm × 70 mm × 76 mm) (Figure 1), fluid in the pleural cavity, enlargement of supraclavicular lymph nodes bilaterally, left subclavian and left diaphragmatic nodes and lung infiltration. The histopathological examination at the diagnosis revealed extensive areas of necrosis and numerous HRS (Reed/Sternberg) cells (CD30, CD15, CD20, CD79a, PAX-5 – positive), and a few cells positive for CD 45 and CD3. Diagnosis from the local laboratory was “B-cell lymphoma unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma”, however final diagnosis after verification in reference central histopathological laboratory was “classical nodular sclerosis Hodgkin’s lymphoma”. Finally, HL, stage IVB was diagnosed (mediastinal tumour, fluid in the pleural cavity, supraclavicular lymph nodes bilaterally, left subclavian, left diaphragmatic node and left lung involvement with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 20 mm).

The patient was treated according to the EuroNet-PHL-C2 protocol, therapeutic level TL-3. Positron emission tomography (PET) examination revealed inadequate early response to treatment after 2 OEPA cycles (prednisone, vincristine, doxorubicin, etoposide). After 4 COPDAC cycles (prednisone, dacarbazine, vincristine, cyclophosphamide) (5 months from the diagnosis), morphological and metabolic progression in the mediastinum and left lung was found. Biopsy of the tumour and drainage of the left pleural cavity was performed. The local laboratory found tissue consistent with HL, howe-ver verification of histopathological examination at the reference centre suggested the diagnosis of unclassified B-cell lymphoma with features intermediate between DLBCL and cHL. The histological examination revealed numerous acidophilic granulocytes and atypical cells, including some with HRS morphology. Immunochemistry showed cell positivity for CD30, CD15, PAX-5, MUM1, LMP/EBV, Bcl-2, Glut-1 and also in CD23, weak positivity for CD20 and CD79a.

The patient received a second-line treatment with three IGEV cycles (vinorelbine, ifosfamide, gemcitabine). Mobilization and apheresis of hematopoietic cells from peripheral blood was performed after the first IGEV cycle. Due to the lack of complete metabolic response in PET after 2 IGEV cycles, it was decided to change chemotherapy to brentuximab vedotin + bendamustine (BV-Be). The boy was trea- ted with two BV-Be cycles. Control CT revealed a second progression of the mediastinal tumour (10 months from the initial diagnosis, 5 months after the first progression).

It was decided to change therapy and use the regimen as for B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (B-NHL). The patient was treated according to the EICNHL COG Inter B-NHL protocol – group B-high. He received a COP cycle (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone) with tumour mass reduction by 60%. Then, 2 R-COPADM cycles (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, methotrexate, prednisone, rituximab, vincristine) were administered. Following the R-COPADM-1 cycle/the first R-COPADM cycle, further tumour regression of approximately 33% was observed.

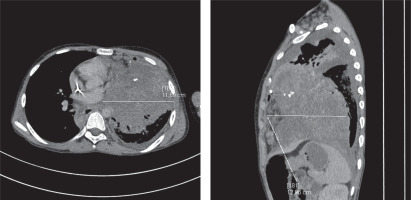

After the R-CYM cycle (rituximab, cytarabine, methotrexate), there was no complete remission (CR), so it was decided to intensify the therapy. The boy received the R-CYVE cycle (rituximab, cytarabine, etoposide, dexamethasone). Due to the appearance of cough and auscultatory abnormalities, a CT scan was performed and disease progression with significant enlargement of the tumour mass in the mediastinum and infiltration of the left lung was found (14 months from the initial diagnosis, 4 months after the second progression). Biopsy of the tumour was performed. In histological examination, atypical cells with morphology of HRS were found. These cells showed positivity for CD30, CD15, PAX-5, weaker positivity for CD79a. In a few cells, CD23 positivity was found and very few of them were positive for CD20, CD3 and a weak expression of LCA was observed. The final diagnosis was mediastinal GZL. The boy received the R-ICE cycle (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide ), however further tumour progression was observed (Figure 2).

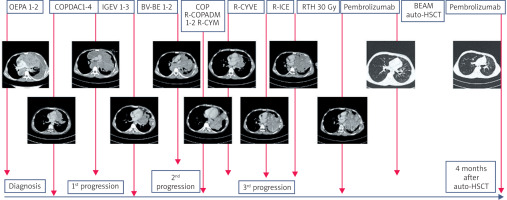

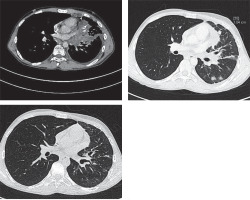

This was followed by radiation therapy of mediastinum (30 Gy). Treatment with pembrolizumab was started at the same time. The dose of 2 mg/kg every 3–4 weeks was used. A follow-up CT scan showed gradual regression of the nodular lesions (Figure 3). The therapy was complicated by fungal pneumonia that occurred 5 months after the start of therapy with pembrolizumab and was successfully treated with antifungal drugs.

Figure 3

Computed tomography (CT) scan showing gradual regression of the tumour on pembrolizumab therapy (last CT scan before the hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, 7 months after starting pembrolizumab)

Six months after starting pembrolizumab, a PET scan showed a complete metabolic response. After eight months of treatment with pembrolizumab, the boy underwent high-dose BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Two months after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), pembrolizumab was switched back on. The patient received a total of 32 do-- ses of pembrolizumab for 27 months. The treatment was finished 41 months after the initial diagnosis and 28 months after the last progression. Follow-up CT scans revealed a stable small residual tumour mass (7 mm × 14 mm × 20 mm) with numerous calcifications in the anterior mediastinum with a complete metabolic response in the PET scan.

At the last follow-up (6 months after completion of the therapy), the patient was in good general condition, active, with no signs of disease or toxicities of the treatment. The course of the disease is presented on Figure 4.

Discussion

This case report shows the difficulties in diagnosis and treatment choice in paediatric patients with GZL. The described patient presented with huge mediastinal tumour with lung involvement. The histopathology was unclear from the beginning with inconsistency of the results between the local and reference laboratory. Similarly, diagnostic difficulties were described by Sławiński et al. presenting a primary pulmonary Hodgkin’s lymphoma case [7]. In our patient first-line therapy was targeted at cHL. Due to poor response to the treatment, then progression of the disease and unclear histopathology, we decided to change our strategy and use B-NHL directed regimen. However, despite an initial partial response, disease progression occurred on that therapy.

The transition between DLBCL and cHL in the course of the treatment has been described by other authors [8], however the mechanism is not fully understood. It is probable that therapy may influence the immunophenotype. Histological and immunophenotypic changes after immunotherapy especially rituximab have been described by other authors [9].

The management of GZL is difficult as this lymphoma subtype does not fit neatly into the categories of HL or DLBCL. There is no specific universally established guideline for GZL due to its rarity so the treatment typically follows the principles applied to these two types of lymphoma.

In a report of Perwein et al. [2] concerning paediatric GZL, most patients received rituximab-based B-NHL-directed therapy as a first-line treatment (DA-EPOCH-R) and two of them recurred as cHL and were treated with HD-BEAM with ASCR. There was one patient in that cohort treated with pembrolizumab but unsuccessfully.

There are some recommendations to treat GZL with either R-CHOP or DA-EPOCH-R, however, these studies primarily focus on adults [10, 11], and there are no specific treatment guidelines for GZL in paediatric patients.

The therapy outcome varies and is influenced by the disease stage and the response to initial therapy. Despite diverse clinical presentations, GZL patients tend to experience a relatively high relapse rate, particularly when compared to primary mediastinal DLBCL or cHL [2, 10, 11]. Similarly, our patient presented with a very aggressive form of the tumour, making it challenging to achieve CR/complete response.

Second-line chemotherapy for GZL described by other authors includes ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide), EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin), ESHAP (etoposide, solumedrol, cytarabine, cisplatin) and ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) [12].

For patients who achieve partial remission or CR with salvage chemotherapy, autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is often the next step. It is considered the standard treatment for patients with relapsed or refractory GZL, particularly after failure of first-line therapies [12]. The chemotherapy conditioning regimens for ASCT depends on several factors, such as disease stage, prior therapies, and response to initial treatments, often borrowing from both Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treatment protocols. The most commonly used conditioning regimens for lymphoma patients include BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan) [13], which is the regimen our patient received.

Radiation therapy may be used as part of a second-line treatment to control local disease. However, this is usually combined with chemotherapy and/or SCT [11, 14]. The described patient was treated with radiotherapy in parallel with introduction of pembrolizumab so it was difficult to assess the effect of radiotherapy itself.

Targeted therapy like anti-PD-1 (pembrolizumab) or antibody-drug conjugate targeting CD 30 (brentuximab vedotin) is now emerging as a novel therapeutic option [5, 15, 16]. To date, the successful use of pembrolizumab in GZL has only been reported in adults. Melani et al. described three patients with GZL successfully treated with PD-1 inhibitors. One received pembrolizumab after DA-EPOCH-R and salvage radiotherapy, followed by allogeneic transplantation. Another achieved a complete metabolic response with pembrolizumab after partial response to DA-EPOCH-R, remaining in remission on day 381. The third patient responded to nivolumab after multiple treatments, including DA-EPOCH-R and brentuximab, and remained in remission on day 161. Rosales et al. reported a patient treated with R-CHOP who received pembrolizumab after disease progression and autologous HSCT [4, 6].

This anti-PD-1 antibody is indicated by the European Medicines Agency for children and adolescents aged 3 years and older with relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma, following failure of ASCT, or after at least two prior therapies when ASCT is not a viable treatment option.

Pembrolizumab is generally well tolerated, with most patients experiencing few or manageable side effects. In our patient invasive fungal infection was diagnosed in the course of the therapy with pembrolizumab, however the patient was heavily pretreated with chemotherapy so that could be also the consequence of the previous treatment. No other treatment-related adverse events of pembrolizumab were observed in the patient. In contrast, the analysis of the KEYNOTE-087 study by Zinzani et al. found that serious adverse events led to treatment discontinuation in some patients, including cytokine release syndrome and infusion-related reactions (both occurring in a single patient), myocarditis, epilepsy, and pneumonitis [9/16]. The most commonly reported adverse events in the study were hypothyroidism, infusion-related reactions, and hyperthyroidism. Additionally, isolated cases of pneumonitis, colitis, iritis, sarcoidosis, myocarditis, and myositis were observed, each in a single patient. There was no treatment-related deaths described in that study. These findings highlight the potential for immune-mediated adverse effects of pembrolizumab, which, although generally well tolerated, require close monitoring during treatment [16].

There are no established guidelines regarding the use of pembrolizumab before and after transplantation [17]. In our case, the patient received the final dose of pembrolizumab one month prior to HSCT, with therapy being reintroduced two months following the transplantation. The patient received a total of 32 doses of pembrolizumab for 27 months.

We decided to stop pembrolizumab treatment after 2 years of the therapy based on the long-term results from the KEYNOTE-087 trial, which showed favourable outcomes for patients who achieved complete remission. Even after discontinuation, these patients had a higher likelihood of long-term survival, with re-treatment possible in case of relapse. The KEYNOTE-204 and KEYNOTE-170 trials also showed sustained remission for up to 2 years of treatment with pembrolizumab in PMBCL and HL patients [18–20].

The limitations of our study is the fact that it is only one case report. However, the follow-up, almost three years from pembrolizumab introduction, and 6 months after completion of the treatment seems to be long enough to assess effectiveness of the therapy. Taking into account the rarity of the condition and difficulties in the therapy of R/R GZL the case seems to be of great value.

Conclusions

We present here successful use of pembrolizumab in the teenage patient with progressive GZL. The use of pembrolizumab should be studied on a larger cohort, but this is difficult due to the rare occurrence, clinical heterogeneity and aggressiveness of the described tumour. We believe that the described case may help clinicians struggling with the treatment of GZL.