Introduction

One of the most common urogynecological diseases in menopausal women is urinary incontinence (UI) – a condition that has an extremely negative impact on the quality of life of patients, causing significant psycho- emotional discomfort, social maladjustment and hygienic inconvenience [1, 2].

According to numerous epidemiological studies, 27–58% of the women suffer from UI during this period of their lives [3, 4]. It should be noted that the majority of patients (about 90%) are diagnosed with mild and moderate severity of UI, 7–11% – with severe degree, which requires surgical intervention [5]. However, many clinicians agree that the actual prevalence of UI cannot be accurately assessed, as the patients are embarrassed to consult a doctor, considering this pathology to be purely intimate and an inevitable consequence of age-related (climacteric) changes.

According to current recommendations of the International Continence Society, adults have five main types of UI: functional, urgent, stress, overflow, and mixed incontinence [6].

Functional incontinence is involuntary UI that is not accompanied by the urge to urinate. In most clinical cases, this is a secondary pathology that occurs in the patients due to significant cognitive or physical impairment, such as progressive degenerative diseases of the central and peripheral nervous system, injuries, etc. [7].

Urgent incontinence (or imperative incontinence) is characterized by a sudden and unbearable urge to urinate, which can lead to involuntary leakage of urine. The amount of urine varies from a few drops to complete emptying of the bladder. Involuntary loss of urine can occur anywhere and at any time, so this type of UI is the most psychologically traumatic for the women, significantly limiting their freedom of movement, social activity, creative expression and cognitive potential. According to studies, the most common causes of this type of UI are acute/chronic infections and neurological disorders [8].

Stress incontinence is involuntary urination during physical exertion, change in the body position, sneezing, coughing, laughing, etc. This type of UI is caused by insufficient urethral resistance in response to a sudden increase in the intra-abdominal pressure, and is not accompanied by detrusor contractions at this moment [9].

Overflow incontinence is a small volume (sometimes drop-like) release of urine from the overflowing bladder. This type of UI is most frequently found in men with hyperplasia or hypertrophy of the prostate gland. In women, this type of UI is formed with/occurs due to incomplete emptying of the bladder and is accompanied by a progressive increase in the volume of residual urine [10].

Mixed incontinence is involuntary urination of mixed aetiology, i.e. it is any combination of the above types of UI. The most common combination is an imperative urge to urinate with stress or functional incontinence [11, 12].

It is important to note that in everyday clinical practice, three types of UI are most frequently diagnosed in women – stress (50–75%), mixed (up to 30%) and urgent – up to 20% of cases [13, 14]. Therefore, it is important for practicing physicians to know the features of the anatomy of the lower urinary tract, to understand the basic mechanisms of urine retention, the pathophysiological aspects of its incontinence, which allows to prevent this pathology in time and to determine the most optimal (personalized) tactics for patient management.

Today two theories are generally accepted (the “hammock” hypothesis, an integral theory of female urinary incontinence), which quite convincingly explain the mechanisms of UI and on which modern surgical methods of treatment are based (colposuspension, sling operations (TVT, TVT-O, TVT SECUR system), injection methods of treatment (Collost gel, Urodex)) [15–17].

The “hammock” theory is based on the peculiarities of the histological structure and anatomical location of the pelvic fascia (PF), which is a continuation of the intra-abdominal fascia and represents a continuous fibromuscular plate. In its appearance, the PF resembles a hammock stretched between the anterior, lateral and posterior walls of the small pelvis, and fixing the urethra, bladder, vagina and cervix with its central part.

The “hammock” theory explains UI as a result of insufficient mechanical pressing of the urethra to the anterior wall of the vagina due to weakening of the ligaments and fascia of the urethrovaginal segment of the pelvic floor, which leads to the inevitable release of urine with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure [18, 19]. The main postulates of this theory are based on the fact that topographically the female urethra is located between the parietal layer of the PF and the vagina. In this case, the posterior surface of the urethra tightly fuses with the anterior wall of the vagina by means of the elastic pubocervical fascia, which in turn is woven into the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex. It is important to add that the female urethra is fixed to the pelvic walls by the pubourethral and urethropelvic ligaments (which are derivatives of the PF). The pubourethral ligaments (anterior, intermediate and posterior) start from the anterior and posterior surfaces of the lower part of the pubic symphysis, go to the middle section of the urethra and encircle it in the form of a loop (this feature is used in sling surgical operations for UI). These ligaments are also connected with the inner edges of the pubococcygeus muscles (the anterior parts of the m. levator ani/levator ani muscle) and are woven into the walls of the vagina. It is the pubourethral ligaments that provide a fixed anatomical position of the urethra and the anterior wall of the vagina in relation to the anterior walls of the pelvis. A decrease in the tone of these ligaments leads to a downward and backward displacement of the urethra as well as to a prolapse of the neck of the bladder. In urogynecology, the pubourethral ligaments are also used for topographic division of the urethra into three parts – proximal, middle and distal. It should be noted that the proximal third of the female urethra provides involuntary retention of urine. A certain role is played by the urethropelvic ligaments, fixing this part of the urethra to the lateral walls of the pelvis, namely to the tendinous arches of the PF (arcus tendineus fascia pelvis). The middle third of the urethra provides both involuntary and voluntary retention of urine in case of a sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure. The distal part of the female urethra functionally represents only a channel for the excretion of urine. Thus, according to the “hammock” theory, the pubourethral and urethropelvic ligaments in combination with the muscular- fascial structures of the pelvic floor provide the physiological location of the urethra and bladder in the pelvic cavity. At that, in case of increased intra-abdominal pressure, m. levator ani/levator ani muscle, muscle fibres of the PF contract, this increases the tension of these ligaments and leads to mechanical pressing of the urethra to the anterior wall of the vagina and retention of urine. It should be noted that, according to many clinicians, this theory does not fully explain the mechanisms of urinary retention/incontinence and has/gives rise/leads to some controversial judgments and statements/is controversial.

Currently, the integral theory seems more logical and convincing, which explains the mechanisms of urination from the standpoint of static anatomy (physiological location of the pelvic organs), dynamic anatomy (displacement of the pelvic organs under the influence of muscle contraction and ligament tone) and functional anatomy (changes in the state of the fibrous- muscular structures of the pelvic floor and pelvic organs during their physiological or pathological functioning) [20, 21]. That is, the processes of UI are considered as a complex disorder of the interaction of the pelvic organs, muscles, ligaments and nerves. At the same time, dysfunction of the connective tissue structures is designated as the most common cause, due to their increased vulnerability.

What are the most common causes of weakening/damage to the pelvic ligament-fascial and myofascial structures in women? Undoubtedly, these are injuries to the muscular-ligamentous apparatus of the pelvic floor during vaginal childbirth and gynaecological operations, changes in the hormonal balance, especially hypoestrogenesis, excess weight, hyperglycaemia/insulin resistance, somatic diseases leading to a constant increase in intra-abdominal pressure (for example, chronic constipation), impaired blood circulation in the tissues and nerve fibres of the pelvis due to chronic inflammatory diseases of the pelvic organs and a sedentary lifestyle [22, 23]. There are really many causes. But all of them have one thing in common – a result of traumatic, histological, biochemical processes, there/that is a decrease in the elasticity and hydrophilicity of the pelvic floor tissues. In this regard, the aim of our work was to study the water balance in menopausal women who suffer from urinary incontinence.

Material and methods

This study involved 265 working women aged 47– 65 years old. We were interested in examining this particular category of patients who lead an active social lifestyle, implement their accumulated life and professional experience, and embody their creative ideas.

The patients were divided into 2 groups:

Group I – 145 menopausal women who suffered from such types of UI as stress, urgent or mixed;

Group II (a control group) – 120 menopausal women who did not complain of urinary incontinence, or could note periodic, but quite rare episodes of stress urinary incontinence.

All patients underwent a thorough analysis of complaints and obtaining a case history. A mandatory component of interaction with the patient was filling out a special 7-day questionnaire, in which it was necessary to indicate the frequency of urination during the day time, the volume of urine excreted, the time and amount of fluid drunk, the characteristics of urination and episodes of urinary incontinence, the characteristics of nutrition and physical activity.

A comprehensive objective and general clinical examinations were carried out following the requirements of modern clinical protocols. The patients of both groups were measured for body mass index, waist circumference, arterial blood pressure, an ECG analysis was performed.

Routine laboratory tests (complete blood count, a comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation tests, a urinalysis, etc.) were used. The levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins, very-low- density lipoproteins, intermediate-density lipoproteins were assessed in order to determine the type of dyslipidemia according to Friedrickson lipoprotein patterns and the cardiovascular risk category. Biomarkers of carbohydrate profile (glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting blood plasma glucose, oral glucose tolerance test, HOMA-IR index)) were estimated.

To assess the functional activity of the ovaries, hormonal panel indices were used follicle-stimulating hormone, anti-Mullerian hormone, inhibin B.

In addition, a general and gynaecological examination was performed. During the speculum examination and bimanual vaginal examination, the condition of the vaginal walls, cervix and body of the uterus, the tone of the pelvic floor muscles, and the ligamentous apparatus of the pelvic organs were assessed. A stress test (cough test) was also performed with a physiologically filled bladder (at least 300 ml).

The patients in both groups were required to undergo translabial ultrasound examination. The following parameters were assessed: urethral length, proximal urethral diameter at rest and at the height of the Valsalva manoeuvre (the manoeuvre duration should be at least 6 seconds), urine volume in the bladder at the time of the study and the volume of post voiding residual, detrusor wall thickness after urination, position and mobility of the bladder neck at rest and at the height of the Valsalva manoeuvre, anterior urethrovesical angle (α), posterior urethrovesical angle (β), deviation of the angles α and β.

Microsoft Excel 2019, Statistica 12.0 computer programs were used to process the study results.

Results

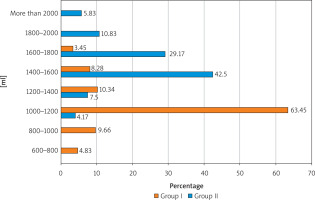

The first stage of our study was the analysis of patients’ complaints and the collection of anamnestic data in order to determine the type of UI and identify possible trigger factors for this pathology, which is extremely important for a practicing physician to develop a personalized prevention and treatment program (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Trigger factors for urinary incontinence in patients of Group I and the Group II (control group)

It was revealed that the most probable trigger factors of UI in the patients of Group I were carbohydrate metabolism disorders (84.14%), complicated vaginal delivery in the anamnesis (71.72%), a sedentary lifestyle (38.62%) and excess body weight (37.93%). We conducted a detailed analysis of carbohydrate metabolism disorders identified in 122 (84.14%) patients of Group I and 19 (15.83%) patients of the Group II. Thus, according to the results of clinical and laboratory examinations, among the patients of Group I, prediabetes was diagnosed in 72 (59.02%) women, insulin resistance – in 14 (11.48%), type 2 diabetes mellitus – in 9 (7.38%), metabolic syndrome – in 27 (22.13%). In the Group II, diagnostic signs of prediabetes were detected in 15 (78.95%) women, insulin resistance – in 3 (15.79%), type 2 diabetes mellitus – in 1 (5.26%). The results obtained indicate an important etiopathogenetic role of hyperglycaemia in UI and should guide the clinician to the detailed examination of metabolic disorders, due to fundamentally different treatment and preventive approaches for their correction.

In our study, complicated vaginal delivery in the anamnesis constituted the second possible cause of UI in Group I patients. When clarifying the anamnestic data, the following features were revealed: macrosomic foetus was delivered in 29 (27.88%) patients of this group, precipitous labour occurred in 10 (9.62%), secondary uterine inertia and prolonged 2nd stage of labour occurred in 46 (44.23%), episiotomy was performed in 82 (78.85%), vacuum extraction of the foetus or obstetric forceps were used in 9 (8.65%). In the Group II, complicated vaginal deliveries in the anamnesis were/occurred in 35 (29.17%), i.e. 2.5 times less frequently.

The next stage of our study was to determine the type of UI in the patients of Group I based on clinical symptoms and ultrasound examination results (Table 1). Thus, stress incontinence was prevalent in Group I patients (59.31%), urgent incontinence was diagnosed in 25 (17.24%) women, and mixed type – in 34 (23.45%). At the same time, mild UI (urine leakage during physical exertion, coughing and with a full bladder) was verified/identified in most patients (97.93%), moderate (urine leakage during walking or light physical exertion) – in 3 (2.07%).

Table 1

Ultrasound parameters of the urethrovesical segment in women with urinary incontinence (Group I) and the control group (Group II)

Translabial ultrasound examination in the patients of Group I compared with the Group II revealed a reliable decrease in the anatomical length of the urethra (28.12 ±2.01 mm, pI-II = 0.049) and an increase in the diameter of the proximal urethra (8.43 ±0.36 mm, pI-II < 0.01). Most patients with UI, pathological tortuosity of the urethra and the appearance of a funnel-shaped expansion of the proximal urethra were also visualized during the Valsalva manoeuvre. We measured and analysed the anterior (α) and posterior (β) urethrovesical angles as well as assessed their deviation (increase) at the height of the Valsalva manoeuvre. In Group I patients, the angle α at rest was 28.98 ±4.03° and in most of them during the Valsalva maneuver it deviated by more than 20° (24.4 3 ±2.27)°, in the women of the control group, these indices were significantly lower and were 16.75 ±3.19°, pI-II = 0.018) and 15.62 ±1.99°, pI-II = 0.004, respectively. The measurements of the angle β at rest, at the height of the Valsalva manoeuvre and its deviation as well as thickness of the bladder wall (detrusor) after urination in the patients of the compared groups did not differ significantly.

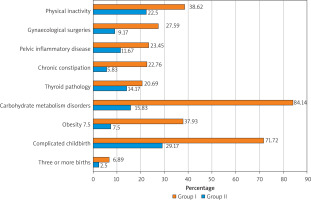

The main stage of our study was a comparative analysis of the fluid intake schedule in the patients of both groups (Figure 2). It should be emphasized that the study was conducted in the autumn-winter-spring period of the year. Quite interesting results were obtained. Thus, in the overwhelming majority of the patients of Group I (88.28%) suffering from UI, the daily volume of fluid consumed by them did not meet World Health Organizationrecommendations (30 ml of fluid per 1 kg of body weight). The survey revealed that 600–800 ml per day was taken by 7 (4.83%) women in Group I, 800–1000 ml by 14 (9.66%), 1000–1200 ml by more than half of the patients (63.45%), 1200–1400 by 15 (10.34%). And only 17 (11.73%) women suffering from UI took a sufficient amount of fluid throughout the day. It should be especially noted that 86 (59.31%) patients of Group I consciously reduced their fluid intake due to the fear of ending up with an overflowing bladder at the wrong time and in the wrong place. For example, they were stimulated to drink no more than 100 ml of coffee or tea during breakfast in the morning due to the need to get to work by public transport. According to 17 (11.72%) patients, for the same reason they did not have breakfast at home and had their first meal at work. Such an uncomfortable start to the working day is a significant stressful situation, negatively affects the processes of digestion, metabolism and is very psychologically traumatic for a woman. The results of the questionnaire also showed that patients with UI noted not only a decrease in daily fluid intake, but, importantly, its uneven intake throughout the day. The situation was opposite in the Group II (control group) patients: 106 (88.33%) patients maintained a sufficient and regular fluid intake, and only 14 (11.67%) women used less than 1400 ml of fluid per day.

Discussion

According to many patients, UI is an “inconvenient” topic to discuss with a doctor. Therefore, in most cases, women apply for/seek medical aid only in situations where the severity of clinical manifestations already significantly affects the quality of their daily life. Until this point, the women try to adapt to the current situation themselves, changing, sometimes dramatically, their habits, hobbies, and lifestyle in the direction of a sharp decrease in physical activity and limiting their fluid intake schedule [24].

Scientific studies have shown that the process of bladder continence at rest and during physical exertion is quite complex, multifaceted, and is achieved through the coordinated interaction of four key mechanisms:

Resistance of the urethra and the closing effects of its internal and external sphincters;

A certain (physiological) static nature of the urethrovesical segment due to the tone of the ligamentous-muscular structures of the pelvic floor;

Elastic properties of the detrusor and plasticity of the bladder;

Adequate innervation and blood supply to the pelvic organs.

It is important to emphasize that the functioning of each of the listed mechanisms from a modern perspective depends on the density of adrenergic receptors (α-1 (α-1A, α-1B, α-1D, α-1L), α-2 and β-), M-cholinergic receptors (M-1, M-2 and M-3) in the tissues of the urethrovesical segment and the modulating influence of sex steroids (estradiol, progesterone, testosterone) [25, 26]. Closely interacting, they provide a regulation of NO-mediated and endothelium-independent (neuron-mediated) vasodilation, effective metabolism, trophism and energy metabolism in the tissues, synthesis of collagen and elastin, a fully functional state of the urothelium as well as local (secretory) immunity (sIgA, IgM). These are the postulates on which the principles of drug treatment of UI in women are based [27].

However, urination disorders in women in menopause cannot always be explained only by hormonal imbalance, metabolic disorders due to somatic disea-ses or traumatic injuries to the structures of the pelvic floor and/or pelvic organs. As our practice shows, the use of hormone replacement therapy, modern surgical methods of treating UI, unfortunately, do not have the expected long-term effects [28, 29]. Therefore, many clinicians agree that the effectiveness of the interaction of multicomponent mechanisms of bladder continence directly depends on the initial hydration of the tissues of the urethrovesical segment. Insufficient daily fluid intake schedule and inadequate water balance are the cause of decreased elasticity, strength, plasticity, compressibility and extensibility of the soft tissues and, as a result, functionality [30].

In our study, the overwhelming majority of menopausal patients suffering from UI showed signs of an unbalanced fluid intake schedule, and therefore it is logical to consider it as a possible risk stratification factor for this pathology.

Undoubtedly, more extensive studies within the framework of meta-analysis will provide detailed results that will allow us to identify patterns in risk distribution and determine the options that have the greatest impact on risk.

Conclusions

The mechanism of bladder continence in women is quite complex and multifunctional. In this regard, the priority tasks of modern clinical medicine are not only the creation of effective protocols containing standardized and scientifically based recommendations for the diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation of patients with UI, but the development of models for risk stratification of this pathology based on individual clinical information about the patient. This will allow for personalizing recommendations for the prevention of UI and forming/making further effective clinical decisions on the management of patients, which reflects modern concepts and principles of evidence-based medicine.