Introduction

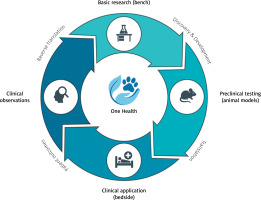

Translational research in cardiology faces a fundamental crisis [1, 2]. Despite decades of investment and thousands of promising discoveries, only 5% of therapies tested in animals ultimately receive regulatory approval for human use [3]. This “valley of death” between preclinical promise and clinical reality stems largely from the limitations of traditional animal models – young, genetically homogeneous laboratory animals with artificially induced diseases that poorly replicate the complexity of spontaneous cardiovascular disease in aging, genetically diverse human populations [1, 2]. The emerging paradigm of reverse translation offers a solution [4–7]. Rather than following a unidirectional path from bench to bedside, this approach creates a continuous cycle where clinical observations drive basic research, which informs better clinical trials, generating new observations (Figure 1) [5]. The One Health initiative provides the operational framework for this bidirectional exchange, formally integrating human and veterinary medicine to leverage naturally occurring diseases in companion animals as high-fidelity models for human conditions [4]. Defined as a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach, One Health recognizes the inextricable links among the health of people, animals, and their shared environment [8]. While its conceptual roots trace to the 19th century, the modern movement gained momentum in the 21st century through collaborations between major medical bodies like the American Medical Association (AMA) and American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), largely in response to growing zoonotic disease threats [4].

Figure 1

The bidirectional translational cycle in cardiovascular medicine. The traditional bench-to-bedside pathway is complemented by reverse translation, creating a continuous cycle of discovery. The One Health approach integrates all stages, recognizing the interconnection between human and animal health

Veterinary interventional cardiology demonstrates this principle in action [4–7]. Procedures like cardiac pacing and balloon valvuloplasty, initially developed through animal experimentation, refined in human medicine, and then adapted for veterinary patients, now generate valuable clinical data that inform the next generation of human devices. This review examines how this translational cycle operates, its economic implications, and the regulatory changes needed to fully realize its potential [4–7, 9].

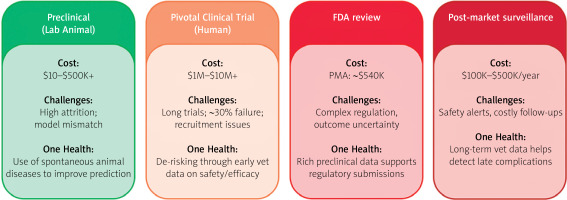

The economic reality of cardiovascular innovation

Bringing a cardiovascular device to market represents a staggering financial commitment. Class II devices approved via the 510(k) pathway cost approximately $30 million to develop, while high-risk Class III devices requiring Premarket Approval average $94 million [10]. Complex therapeutic devices can exceed $500 million when accounting for failed studies. Clinical trials alone cost $1–20 million and take 4–6 years, with failure rates exceeding 30%. FDA user fees add another layer of expense – $24,335 for 510(k) submissions and over $540,000 for PMA applications in fiscal year 2025 [11, 12].

Against this backdrop, veterinary clinical trials offer compelling economic value (Figure 2). A well-designed study in dogs with naturally occurring heart disease provides crucial safety and efficacy data at a fraction of the cost of human trials [12]. More importantly, these studies de-risk development by identifying failure modes early, refining device design based on real-world performance, and selecting optimal patient populations for expensive pivotal human trials. This strategic investment increases the probability of success in later stages, reducing financial exposure for sponsors and investors [13, 14]. However, understanding the cardiovascular system has required a diverse array of animals, from lower organisms to large mammals, each offering distinct advantages and limitations as detailed in Table I [4–7, 9].

Figure 2

Key stages of medical device development with associated costs, challenges, and potential contributions of veterinary (“One Health”) models to enhance translatability and regulatory success

Table I

Comparative analysis of animal models in cardiovascular research

High-fidelity models: spontaneous disease in companion animals

The superiority of spontaneous disease models lies in their biological authenticity. Unlike induced laboratory models, companion animals develop cardiovascular diseases through the same complex interplay of genetics, environment, and aging that drives human disease (Table II) [5–7, 15–17].

Table II

Summary of key interventional procedures and their translational pathway

Canine dilated and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathies: a window into arrhythmogenesis

Canine dilated cardiomyopathy provides exceptional insight into heart failure pathophysiology [9, 15]. The tachycardia-induced canine model faithfully replicates the neurohumoral activation characteristic of human heart failure, with marked elevations in plasma norepinephrine, epinephrine, renin, and aldosterone [15, 18]. Most critically, it reproduces the specific electrophysiological remodeling underlying sudden cardiac death – prolonged action potential duration and increased spatial dispersion of repolarization that create substrate for lethal arrhythmias. This makes it invaluable for testing anti-arrhythmic therapies. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) occurs spontaneously in Boxer dogs, providing a naturally occurring animal model that faithfully recapitulates the clinical and pathological features of human disease [19, 20]. This canine model exhibits the hallmark characteristics of ARVC: ventricular tachycardia originating from the right ventricle, progressive structural abnormalities including right ventricular dilation, and the pathognomonic histological triad of myocyte loss, fibrofatty replacement, and inflammatory infiltrates [21]. Affected dogs demonstrate myocardial apoptosis and may experience sudden cardiac death, paralleling the human phenotype [22]. Notably, familial clustering of cases has been documented, supporting an inherited basis for canine ARVC and further strengthening its validity as a translational model for understanding the genetic mechanisms underlying this cardiomyopathy.

Canine subaortic stenosis: natural experiments in disease management

Subaortic stenosis in dogs offers unique translational opportunities through its divergent management compared to humans [23]. Certain breeds, such as Boxers, show high disease prevalence, providing genetically concentrated populations for investigating hereditary disease basis [23–25]. While human patients undergo surgical resection, dogs are managed medically with β-blockers. This creates a natural experiment – decades of veterinary data on disease progression under conservative therapy that could never be ethically obtained in humans. The discovery of PICALM gene mutations in Newfoundland dogs with subaortic stenosis provides a concrete genetic target for investigating disease mechanisms [23, 26]. The shared pathophysiology – abnormal aortoseptal angle generating high shear stress and driving fibrous ridge formation – ensures direct relevance to human disease [23].

Additional models

Canine heartworm disease (Dirofilaria immitis) provides a natural model for pulmonary hypertension through chronic inflammatory endarteritis [27]. Also, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in West Highland white terriers serves as a natural model of this disease [28, 29]. Patent ductus arteriosus, the most common congenital defect in dogs, offers insights into volume overload pathophysiology and device closure techniques. Also, increased pressure in the left atrium resulting in left-sided congestive heart failure is a common sequela to multiple cardiac conditions in dogs, with the most common being myxomatous mitral valve disease [15]. These spontaneous models share environmental exposures, genetic diversity, and comorbidities with human patients, providing data superior to any laboratory simulation [5–7, 15–17].

Case studies in translational success

Patent ductus arteriosus: completing the circle

Patent ductus arteriosus closure exemplifies the full translational cycle [30–32]. After surgical ligation’s introduction in 1938, researchers developed transcatheter devices tested extensively in canine models [32, 33]. The Amplatzer Duct Occluder underwent rigorous evaluation in dogs before human use, ultimately leading to the Amplatzer Canine Duct Occluder – the first device designed specifically for canine anatomy. Today, transcatheter patent ductus arteriosus closure is standard care in veterinary medicine, generating continuous data on device performance that inform next-generation human pediatric occluders [33, 34].

Balloon valvuloplasty: veterinary patients leading the way

In a remarkable reversal of the typical pathway, the world’s first balloon valvuloplasty was performed on an English Bulldog with pulmonic stenosis in 1980, 2 years before the first human case [35]. This veterinary success provided crucial proof-of-concept enabling human application. Today, balloon valvuloplasty remains the treatment of choice for canine pulmonic stenosis [36, 37]. However, long-term human studies reveal significant pulmonary regurgitation in up to 29% of patients – a complication less studied in dogs, presenting a clear opportunity for veterinary research to inform human practice [36].

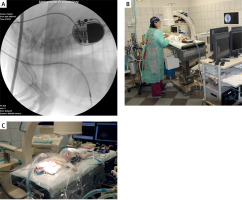

Cardiac pacing: a century of innovation

The development of cardiac pacing began with Bigelow and Callaghan’s 1950 demonstration of transvenous pacing in dogs [38]. This foundational work enabled all subsequent advances in both human and veterinary pacing [39]. Today, pacemaker implantation in dogs achieves excellent outcomes (86% 1-year survival), though complication rates (13–35%) mirror human experience [40]. The shared challenge of lead-related complications makes long-term veterinary data invaluable for predicting device durability and refining management protocols. The Department of Internal Medicine with Clinic of Diseases of Horses, Dogs and Cats at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences, has performed cardiac pacemaker implantation in dogs since 1992. The program predominantly utilizes single-chamber pacemakers, particularly in small and miniature breed dogs. Current procedural volume averages 20 implantations annually (unpublished data, Figure 3 A). The primary indications for pacemaker therapy include third-degree atrioventricular block with ventricular escape rhythm and symptomatic paroxysmal second-degree atrioventricular block presenting with syncope. Unlike human procedures performed under conscious sedation, canine pacemaker implantation requires general anesthesia, representing a key procedural distinction between veterinary and human electrophysiology practice.

Figure 3

Cardiac electrophysiology procedures in a canine model. A – Fluoroscopic image demonstrating implanted cardiac pacemaker with visible lead placement in a canine subject. B, C – Procedural setup during cardiac electrophysiology study and radiofrequency catheter ablation, showing patient positioning and equipment arrangement. Images courtesy of Prof. Agnieszka Noszczyk-Nowak, Department of Internal Medicine and Clinic of Diseases of Horses, Dogs and Cats, Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences, Poland

Radiofrequency ablation: from crude to curative

Catheter ablation evolved from Scheinman’s initial direct current (DC) shock experiments in dogs through meticulous refinement to today’s precise radiofrequency techniques [41]. The technology now offers > 98% cure rates for accessory pathway-mediated tachycardias in dogs [42]. Veterinary experience with challenging anatomies and novel mapping systems continues to inform human electrophysiology [43–45]. In Europe, catheter ablation procedures in dogs are performed at three specialized centers: the Veterinary Department of Ghent University, Clinica Veterinaria Malpensa, and the Department of Internal Medicine with Clinic of Diseases of Horses, Dogs and Cats at Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences, Poland [46]. The Polish center pioneered ablation therapy in the country in 2010, collaborating with electrophysiologists from the 4th Military Hospital in Wroclaw. Since inception, the Wroclaw veterinary team has successfully performed ablations for accessory pathway-mediated tachycardias, focal atrial tachycardia, and ventricular premature complexes (Figures 3 B, C). Notably, many patients presented with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, which demonstrated complete or partial reversal following successful arrhythmia ablation, paralleling outcomes observed in human electrophysiology [18].

Septal defects: the importance of anatomical fidelity

Atrial septal defect closure device development revealed critical lessons about model selection [47, 48]. Early devices tested successfully in dogs failed to account for anatomical differences in atrial septum structure. Researchers pivoted to porcine and ovine models with more human-like anatomy, demonstrating that model fidelity trumps convenience [49–51]. Despite this, modern devices like the Amplatzer Septal Occluder are now successfully used in selected canine patients.

Transcatheter edge-to-edge repair in canine mitral valve disease: the V-Clamp system

While percutaneous mitral valve repair using the MitraClip system (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, Chicago, IL, USA) has been successfully employed in human medicine since 2008, device dimensions preclude its use in veterinary patients [52–54]. To address this gap, the V-Clamp (HongYu Medical Technology, Shanghai, China) was developed as a species-specific transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER) device for canine myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD). The V-Clamp functions by approximating mitral valve leaflets to reduce regurgitant flow, thereby improving cardiac hemodynamics. The device demonstrates optimal efficacy when regurgitation is localized to specific leaflet segments without cleft pathology. Compared to conventional open-heart surgery, this minimally invasive approach eliminates the need for cardiopulmonary bypass, significantly reduces procedural time, and minimizes perioperative morbidity. Initial clinical studies have demonstrated promising safety and efficacy profiles for the V-Clamp in dogs with MMVD [55, 56]. However, comprehensive evaluation awaits longer-term follow-up studies with larger patient cohorts to establish definitive outcomes and refine patient selection criteria.

The return journey: clinical insights driving innovation

The true power of reverse translation emerges when veterinary clinical experiences generate new research questions [5–7, 15–17]. When patients respond unexpectedly to therapy, these “clinical puzzles” drive investigations into novel mechanisms and applications. Veterinary hospitals functioning as clinical research sites provide real-world device performance data impossible to obtain in laboratory settings [57, 58]. Successful collaborations demonstrate this synergy: University of Florida’s joint human-veterinary team pioneered hybrid surgical-interventional techniques; Colorado State University’s advanced imaging integration provides real-world performance data to manufacturers while delivering cutting-edge care to animals; multi-institutional registries track long-term outcomes across species (Table III). This bidirectional exchange accelerates innovation while expanding access to advanced therapies [59].

Table III

Examples of One Health collaborations in cardiovascular medicine

Regulatory evolution: bridging the gap

Current FDA guidance for animal studies makes no distinction between induced disease in laboratory animals and spontaneous disease in clinical patients. This regulatory gap creates uncertainty for sponsors considering veterinary clinical trials, forcing continued reliance on less predictive traditional models [60]. A new FDA-CVM guidance document should establish clear pathways for including veterinary clinical data in human device submissions, addressing study design standards, data collection requirements, ethical oversight, and reporting formats. This evolution would align regulatory frameworks with scientific reality, accelerating safer therapies to market [60–62].

The clinical reality: technology and expertise

Modern veterinary interventional cardiology requires sophisticated infrastructure (Table IV) [63–65]. Fusion imaging systems like Philips EchoNavigator combine echocardiography’s soft tissue detail with fluoroscopy’s device visualization, enabling complex structural repairs. Specialized anesthetic protocols balance adequate sedation with cardiovascular stability [66]. Advanced biomaterials – nitinol’s shape memory, anti-thrombogenic coatings, endothelialization-promoting surfaces – enable long-term device success [67].

Table IV

Imaging modalities in interventional cardiology

Board certification in veterinary cardiology requires completion of research projects and rigorous examinations through either the American or European College of Veterinary Internal Medicine. The scarcity of residency positions globally has created a critical shortage of veterinary cardiologists, resulting in significant geographic disparities in access to specialized cardiac care. This challenge is particularly acute in countries like Poland, where no veterinary cardiology residency programs currently exist. To address these limitations, many veterinary centers have established collaborative partnerships with human cardiology departments. These interdisciplinary collaborations enhance procedural expertise, improve patient safety, and advance the standard of care through shared knowledge and technical resources.

Procedure costs ($5,700–7,000) and insurance limitations pose ethical challenges, forcing clinicians to balance technological capabilities with economic realities while maintaining patient welfare [68].

Future directions: convergent technologies

Emerging innovations promise to revolutionize cardiovascular care across species (Figure 4). Miniaturized devices like leadless pacemakers eliminate lead complications; experimental bioresorbable devices dissolve after restoring the function [69]. Artificial intelligence enables predictive medicine through automated arrhythmia detection and disease staging [70–72]. 3D printing creates patient-specific implants [73, 74]. Precision medicine uses genetic profiling and biomarkers to individualize therapy [75, 76]. These technologies, developed through bidirectional translation, will create increasingly predictive, preventive, and personalized cardiovascular care. More importantly, their convergence will transform today’s untreatable conditions into manageable diseases, fundamentally reshaping the therapeutic landscape of veterinary cardiology [77].

Conclusions

Veterinary interventional cardiology demonstrates that the future of translational medicine is cyclical, not linear. By embracing spontaneous disease models in companion animals, leveraging economic advantages of veterinary trials, and creating regulatory frameworks that recognize their value, we can overcome the valley of death that has long plagued cardiovascular innovation. The One Health approach transforms veterinary medicine from a recipient of human medical advances to an active partner in discovery. This bidirectional bridge ensures that insights flow continuously between species, accelerating progress toward safer, more effective therapies for all. As we advance toward an era of miniaturized, intelligent, and personalized cardiovascular interventions, the lessons learned from our animal companions will prove more valuable than ever.