Newer structural heart interventions such as transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) and transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER) of the mitral or tricuspid valve have gained considerable ground in contemporary clinical practice due to their proven safety and efficacy. They were previously restricted exclusively to patients at very high risk (STS score ≥ 8) or with a surgical contraindication; nevertheless, recent studies have found them to be comparable to the open approach in terms of short- and long-term outcomes, even in intermediate-risk patients and with future trends towards low-risk patients [1, 2]. The imminent exponential expansion of transcatheter cardiac treatments and the progressive growth of candidates have made us question whether the cardiovascular surgeon has been relegated to the transcatheter heart team (THT) or whether it is time to take a step forward and immerse ourselves in the evolution of the specialty towards transcatheter cardiac surgery.

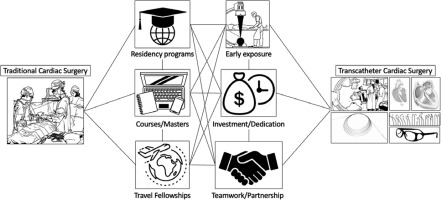

Two major pathways have been proposed to achieve transcatheter training and excellence as a primary operator: completion of an interventional cardiology program or cardiovascular surgical residency; or the possibility of a formal proctorship in a high-volume center with trained operators [1]. However, in the real world, graduation from a cardiovascular surgery program is not sufficient, as the surgeon should have previously extensive experience in open aortic valve surgery (at least 100 cases, or 50 cases over 2 years, and should spend at least 50% of his active practice in the transcatheter center) and comprehensive knowledge of tomographic image planning and processing. According to the STS database, only 15.3% of transcatheter cardiac treatments in the United States (US) were performed by cardiac surgeons (~5–9 cases monthly); and many of them were also actively involved in the critical steps of device deployment above the average offered by interventional cardiologists such as obtaining and repairing alternative vascular access (89% vs. 65%) [2]. There is no doubt that cardiovascular surgeons have unique and advantageous skills to offer a full therapeutic spectrum of structural heart disease; in addition, they can offer minimally invasive, multivalvular approaches, a free choice of vascular access site (femoral, carotid, axillary, or transapical), and all in a single hybrid surgical environment, making them the valvular surgical specialists par excellence. Despite the above, it is mandatory to understand that these endovascular skills should be developed and implemented early in cardiovascular surgical residency programs. However, recent surveys of residents showed alarming results: 82% had never manipulated wires, or had any contact type with cine-angiography or C-arm during their surgical training, and 89% wished they had received training in transcatheter cardiac therapies [3]. Given that this problem is increasingly spreading around the world and is not foreign to Latin America, organizations such as the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education curriculum for cardiothoracic surgical training in the US have been mandatorily implementing that, since 2017, all residents graduating from cardiothoracic surgery programs must have performed at least 5 transcatheter cardiac procedures as primary operators and assisted at least 10 as secondary assistants [4]. These fledgling initiatives will soon spread around the world, and the success of transcatheter cardiac surgery will be based on accepting that many procedures are becoming less invasive and require additional transcatheter skills, that residents and surgeons-in-training must learn these procedures allowing for professional growth and survival, and that a failure to adapt or evolve will lead to the marginalization of our specialty in the THT (Figure 1).

Being a transcatheter cardiac surgeon is more than a new name; it is a way to generate a new identity for the interventional team. Nonetheless, this empowerment should not lead us down the path of rivalry and competition with interventional cardiologists, so the success of a transcatheter structural heart program is based on collaboration, allowing for comprehensive professional growth for the benefit of the cardiovascular patient [4, 5]. This proposed model has been recently implemented in our center, as one of the few in Latin America where cardiac surgeons actively participate hand in hand with interventional cardiologists, from the identification of the potential patient for a structural transcatheter approach, case discussion, tomographic processing and planning, and with the final deployment of the device. This joint and articulated workflow is under constant mentoring supervised by a senior interventional cardiologist during the first cases as the primary operator; and later, with adequate training and case volume, the transcatheter cardiac surgeon obtains his interventional autonomy, but always with multidisciplinary teamwork.

On the other hand, many cardiovascular surgeons of the “older” generation were reluctant and skeptical of the structural cardiac interventionism train, while some “middle-aged” surgeons, being more visionary and pragmatic, jumped on board in time, being highly committed and playing a very important educational role for future generations of surgeons. This growing generation of highly competent and talented cardiac surgeons, whose surgical training predates the diversification of transcatheter therapies and who have not acquired sufficient endovascular skills, achieved higher expertise with the initiative to train themselves adequately through virtual reality training, continuing medical education-supported courses or masters, traveling fellowships, collaboration with heart team colleagues, and industry support. On the other hand, surgeons of the “young” generation have a great responsibility to be trained in the latest transcatheter techniques, with active participation and the great possibility of being the ones in charge of driving this train, faster, more safely – as long as they know how to work as a team and with the highest standards of cardiovascular care.