Left ventricular (LV) pseudoaneurysm develops after rupture of the ventricular wall in an area of pericardial adhesion and organized hematoma. It usually occurs several weeks after the myocardial infarction of the inferior or posterolateral left ventricular wall. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are life-saving for patients with LV pseudoaneurysms.

Sometimes, pseudoaneurysms may remain clinically silent, and be discovered during routine investigations. These patients can be asymptomatic, or present after extensive enlargement of the false aneurysm with other non-specific symptoms like masses on the chest or abdomen [1].

We describe a patient who suffered from silent myocardial infarction presenting at the hospital with a strange pulsatile subxiphoid mass.

A 64-year-old man was admitted to our institution with a pulsatile mass in the subxiphoid region. In medical history he had a past myocardial infarction 10 years before. On palpation, the softball mass, was pulsating in synchrony with the heart rhythm. The first suspected diagnosis in the emergency department was the abdominal wall hernia. Signs of past inferior myocardial infarction were detected on ECG that demonstrated inferior lead Q waves. His functional and exercise capacity was greatly impaired during the last 6 months. On physical examination there was no evidence of heart failure. Hematological and biochemical tests were normal. Chest radiography revealed enlargement of the cardiac silhouette.

After consultation with the cardiologist, transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated an LV systolic function of 50% and a second cardiac chamber with a narrow neck adjacent to the inferior LV wall. The suspected pseudoaneurysm communicated with the left ventricle cavity through an opening of 3 cm. The mass was growing slowly in the past 6 months and it was 10 × 10 cm in diameter by echocardiography.

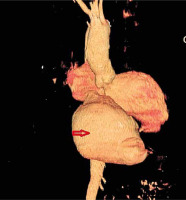

The patient underwent cardiac computed tomography and cardiac catheterization (Figure 1). Left ventriculography showed inferior and postero-basal hypokinesis with mild mitral regurgitation. In addition, a large pseudoaneurysm was demonstrated which originated from the inferior wall measuring 10 × 10 cm with a neck of 3 cm. Coronarography was performed and showed an occluded right coronary artery and non-critical stenosis in the anterior descending and obtuse marginal artery.

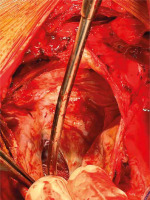

The patient was operated urgently. Standard monitoring techniques and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) were used, confirming the previous information about the pseudoaneurysm. Cardiopulmonary bypass was established by arterial cannulation in the distal ascending aorta and double stage right atrial cannula. Blood cardioplegia was used. Pericardium was adhered to the heart over the right ventricle. A pulsating mass was noted between the diaphragm and the right atrium making the right and the left ventricle invisible. The redundant pseudoaneurysm was opened, and the defect on the LV wall was closed with Teflon patch and a continuous prolene 4.0 suture. The wall of the pseudoaneurysm was closed over (Figure 2).

The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the 7th postoperative day. At his 6 months’ and 2 years’ follow up, the patient was in good condition, echocardiography showed good LV function with an ejection fraction of 50%. The computed tomography excluded the remaining pseudoaneurysm sac and creation of a new one. The patient is free of symptoms, 2 years now from the operation.

Classically, left ventricular pseudoaneurysm results from a cardiac-free wall rupture contained by adherent pericardium or scar tissue as an uncommon complication of myocardial infarction, but nowadays we have also reported cases after cardiac surgery, trauma, and even endocarditis [2]. Although often challenging to make the differential diagnosis, advances in noninvasive imaging improve the ability to distinguish aneurysm from pseudoaneurysm. LV pseudoaneurysm has more chances to develop after an inferior wall myocardial infarction (MI) rather than an anterior wall MI. So, pseudoaneurysms are located often on the posterior, lateral or inferior surfaces of the LV. On the other hand, only a minority of LV true aneurysms are located at the posterolateral or diaphragmatic surface [3]. The incidence of rupture for the pseudoaneurysms is up to 30–45% with a mortality of 48% after conservative treatment and 23% after surgical repair [4].

The indication for surgical treatment is clear in an acute contained rupture of the myocardium with pseudoaneurysm formation which is vulnerable to sudden expansion, rupture and death. Operation should be delayed as much as possible in a stable patient in order to have more scar/stable fibrotic tissue for the secure surgical closure of the defect in the ventricular wall. Surgery may be recommended also for unresponsive arrhythmia, peripheral embolism, or heart failure related to a pseudoaneurysm in chronic cases [5]. However, sometimes it is difficult to determine the time of the false aneurysm formation. Nowadays, a decreased perioperative mortality of 10% is reported due to improvements in the surgical technique [4].

Technically, the neck of the pseudoaneurysm can be closed directly or with a pericardial/synthetic patch trimmed to the size of the defect on the ventricular wall. The remaining tissues of the false aneurysm can be closed over for reinforcement. In our patient, clinical data, echocardiographic and ventriculographic findings were compatible with the diagnosis of a giant and chronic LV pseudoaneurysm with a narrow neck of 3 cm and a diameter of 10 cm. Transthoracic echocardiography is the first diagnostic tool, but further imaging studies should be performed. Ventriculography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of LV pseudoaneurysm. TEE, cardiac computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the other sensitive imaging techniques in the detection of LV pseudoaneurysms. However, sometimes it may be challenging to diagnose LV pseudoaneurysm because of the ambiguity in its presentation; thus, making the diagnosis in a timely manner is crucial. A high index of clinical suspicion and routine echocardiographic screening for detection of LV pseudoaneurysm are essential to improve the outcome in these patients [6]. We think this case is unique due to the rare presentation like an epigastric mass misjudged for hernia at the first glance, and also to the extreme size reached over 10 years after a silent MI. We found only a recent report of such a case after cardiac surgery. The patient had a recurrent false aneurysm which pulsated at the xiphoid region [7].

In conclusion, left ventricular pseudoaneurysm is a rare complication of MI with several cardiovascular complications. In this strange case, the pulsatile epigastric mass was the first presenting symptom bringing the patient to the hospital. Surgery should always be considered as the first option and remains a standard of care for myocardial pseudoaneurysms even in high-risk patients.