Introduction

Retinoblastoma is a malignant, intraocular tumor of the developing re-tina [1]. It is the most common ocular tumor in children, with a prevalence of around 1 : 18,000, which develops mostly within early childhood [2]. Retinoblastoma is caused by mutations in both alleles of the tumor suppressor gene RB1, which encodes the retinoblastoma protein. The mutations cause loss of function of the retinoblastoma protein and result in excessive cell growth due to the lack of cell cycle inhibition [3].

Current treatment regimens include chemo-, cryo-, thermo- and brachy-therapy, by which complete remission of the tumor and preservation of the patient’s eyesight can ideally be achieved [4]. The overall prognosis for the patient is variable and depends on several factors, most importantly the time of diagnosis; the earlier the tumor is detected and treated, the higher are the chances to preserve the children’s vision [1]. Interestingly, a recent study showed a strong correlation between the time of diagnosis and the country the children live in – patients from high-income countries (14.1 months) were diagnosed significantly earlier than patients from low- income countries (30.5 months). Furthermore, only 0.3% of patients from high-income countries had metastasis, whereas this was the case in 18.9% of the patients from low-income countries [5]. The presence of metastasis is associated with a worse prognosis, and untreated retinoblastoma leads to the death of the patient [1, 6].

Eukaryotic (translation) initiation factors (eIFs) are proteins that are essential for the translation of mRNAs in all cells and have thus a fundamental function for the regulation of gene expression [7]. Eukaryotes possess about ten eIFs, which are mostly protein complexes formed from several subunits. eIF4a belongs to the DEAD-box proteins and has enzymatic helicase activity, which is important for the unwinding of double-stranded RNA. eIF4a is further required for binding of the mRNA to the 40S subunit of the ribosome [8, 9]. eIF4e binds to the cap-structure at the 5' end of the mRNA and is part of the so-called eIF4F pre-initiation complex [10]. While all cells express eIFs to ensure proper mRNA translation, the abnormal increased expression of some eIFs has been reported in different tumor entities [11]. Elevated amounts of eIF4a have been found in hepatocellular carcinoma [12] as well as increased expression of eIF4e in, for example, tumors of the lung [13], the prostate [14], and the liver [15]. An analysis of eIF4a and eIF4e expression in tumors of the eye has to the best of our knowledge not been performed to date.

In the present study, we analyzed the expression of eIF4a and eIF4e in 30 retinoblastoma samples and other ocular diseases via immunohisto-che-mistry and quantified them via an immune reactivity score. Furthermore, we determined the expression of eIF4a and eIF4e in the two retinoblastoma cell lines WERI-Rb1 and Y79 via western blot. Lastly, we evaluated the influence of the eIF inhibitor 4EGI-1 on the cell viability of both cancer cell lines.

Material and methods

Reagents

The following primary antibodies were used: eIF4a (#2490), eIF4e (#9742), and GAPDH (14C10, #2118) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, United States). Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked antibody (7074) was used as secondary antibody and was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. The eIF4e/eIF4g inhibitor 4EGI-1 was purchased from Calbiochem (Merck Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

Cell lines and cell culture

The cell lines WERI-Rb-1 (ATCC-HTB-169, [16]) and Y79 (ATCC-HTB-18, [17]) were both obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scien-tific, Waltham, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (PAN-Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany). Both cell lines were kept at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a standard incubator with a water-saturated atmosphere, as described previously [18].

Immunohistochemical staining of the tumor sections

Rabbit antibodies against eIF4a (#2490) and eIF4e (#9742) (both from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) were used to assess eIF4a and eIF4e expression by immunohistochemistry. Staining was performed using the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg (# 122/17).

Immune reactivity score

The expression of eIF4a and eIF4e was assessed by two independent individuals. In order to determine the immune reactivity score, we used a slightly modified version of a previously published procedure [19]. In brief, we rated the intensity score (IS) as “0” (no staining), “1” (weak staining), “2” (moderate staining) or “3” (strong staining) and determined the actual percentage of tumor cells with a positive staining signal (ranging from 0 to 100 %, termed the staining density). Conversion to a numeric scale (termed proportion score [PS]) and determination of the immune reactivity score by multiplying IS and PS were performed as described previously [19].

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed in principle as describ-ed previously [20]. Thirty micrograms of total cell lysate per lane were separated by SDS-PAGE on 12.5% gels and transferred to 0.2 µm nitrocellulose membranes. We ensured the successful transfer of proteins by staining of the membranes with 2% ponceau solution. Membranes were blocked in tris-buffered saline supplemented with 5% skimmed milk powder for 1 h at room temperature. Afterwards, the membranes were washed repeatedly with TBS-T (TBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20) and incubated with the primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Primary antibodies were diluted as follows: eIF4a 1 : 1,000; eIF4e 1 : 1,000; GAPDH 1 : 1,000 (all antibodies diluted in TBS-T with 5% bovine serum albumin). After washing three times with TBS-T, the membranes were incubated with the secondary antibody (diluted 1 : 2,000 in TBS-T supplemented with 5% milk powder) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were again washed with TBS-T and afterwards incubated with immobilon western HRP substrate (Millipore by Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and detected using the GeneGnome XP and the GeneSnap software (Syngene Bio Imaging, Cambridge, United Kingdom). In the event that multiple eIF proteins were detected on a single membrane, the membrane was incubated in 20 ml of Stripping Puffer (Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer, Thermo Scientific) overnight at room temperature to remove bound antibodies. Afterwards, membranes were washed three times for 5 min with TBS-T, blocked again and incubated with another anti-eIF antibody or with anti-GAPDH to detect the protein used as the loading control.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was analyzed using the CellTiter-blue assay (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) as described previously [18, 21, 22]. In brief, 7,500 WEHI-Rb-1 or 5,000 Y79 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate. Different concentrations of the inhibitor 4EGI-1 were added in triplicate. As controls, either an equal amount of the solvent DMSO was added or the same volume of medium, both also in triplicate. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a standard incubator for either 24 h, 48 h or 72 h. In order to determine the cell viability, 20 µl of the cell titer blue reagent was added to each well. The fluorescent intensity was measured at 590 nm for 60 min using FLUOstar Omega (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) and normalized to the value measured at the 0 min time point.

Statistical analysis

Data from cell viability assays were analyzed by one-way ANOVA following Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Immune reactivity scores were statistically analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test following Dunn’s multiple compa-risons test. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA, www.graphpad.com). Further details are given in the respective figure legends.

Results

Expression of the eukaryotic initiation factors eIF4a and eIF4e in ocular diseases

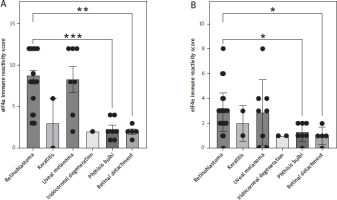

In order to determine whether the two eukaryotic initiation factors eIF4a and eIF4e might have a functional role in retinoblastoma, we analyzed their expression in 30 human retinoblastoma samples. We compared these to samples from patients with other diseases of the eye, including keratitis (two samples), uveal melanoma (eight samples), iridocorneal degeneration (two samples), phthisis bulbi (seven samples) and retinal detachment (five samples). We performed immunohistochemical staining for both proteins on sections and scored their expression using an immune reactivity score. Unfortunately, we could not obtain information regarding eIF4a expression in one sample of uveal melanoma and one sample of iridocorneal degeneration.

Expression of eIF4a was the highest in retinoblastoma (8.77 ± 0.61) compared to keratitis (3.0 ± 3.0), uveal mela-noma (8.29 ± 1.54), and iridocorneal degeneration (2.0), and significantly higher compared to phthisis bulbi (2.29 ± 0.47, p = 0.0009) and retinal detachment (2.0 ± 0.32, p = 0.0025, Fig. 1A). We observed a similar picture when we performed staining and scoring for eIF4e. Expression of eIF4e was the highest in retinoblastoma (2.90 ± 0.29) compared to keratitis (2.0 ± 1.0), uveal melanoma (2.88 ± 0.93), and iridocorneal degeneration (1.0). Likewise, expression in retinoblastoma was significantly higher compared to phthisis bulbi (1.29 ± 0.29, p = 0.03) and retinal detachment (1.0 ± 0.33, p = 0.02, Fig. 1B). In summary, our immunohistochemical analysis revealed increased expression of eIF4a and eIF4e in retinoblastoma.

Figure 1

Expression of the eukaryotic initiation factors eIF4a and eIF4e in ocular diseases. Immune reactivity score of (A) eIF4a and (B) eIF4e in sections of different ocular diseases. Sections from retinoblastoma (n = 30), keratitis (n = 2), uveal melanoma (n = 7 for eIF4a, n = 8 for eIF4e), iridocorneal degeneration (n = 1 for eIF4a, n = 2 for eIF4e), phthisis bulbi (n = 7), and retinal detachment (n = 5) were analyzed. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM, and each sample is further shown as an individual data point. Statistical analysis was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Expression of eIF4a in two retinoblastoma cell lines under treatment with 4EGI-1

Having ascertained that retinoblastoma expresses high amounts of eIF4a, we wanted to investigate whether this is also true for retinoblastoma cell lines. For this, we used the established cell line WERI-Rb-1, which was isolated from a one-year-old girl with retinoblastoma [16], and Y79, which stems from the retina of a 2.5-year-old girl with retinoblastoma [17]. Further, we were interested to investigate whether the eIF4e/eIF4g inhibitor 4EGI-1 would affect the amount of eIF4a present in the cell lines. In order to investigate this, we cultured both cell lines for 24 h with different amounts of 4EGI-1 (3.125–100 µM, respectively) and either with the same amount of DMSO as solvent control or with medium alone. Afterwards, the cells were lysed and the amount of eIF4a in the cell lysate was determined via western blot. As shown in Figure 2A, we could detect eIF4a in all samples of the WERI-Rb-1 cell line, and densitometric analysis of replicate experiments revealed no significant difference in the amount of eIF4a after treatment with 4EGI-1 (Fig. 2A). When we performed the same experiment with Y79 cells, we could also detect eIF4a in all samples via western blot, and the densitometric analysis again showed no significant difference in the amount of eIF4a when the cells were treated for 24 h with the inhibitor (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2

Expression of eIF4a in two retinoblastoma cell lines under treatment with 4EGI-1. A) WERI-Rb-1 cells were treated with different concentrations of 4EGI-1 (3.125–100 μM), DMSO as solvent control or medium alone for 24 h. Cells were lysed and the amount of eIF4a in the cell lysate was analyzed by western blot. GAPDH was analyzed to verify equal loading. One representative experiment is shown. The quantification of three independent experiments (eIF4a/GAPDH) is shown as a bar chart (mean ± SEM) below the western blots. B) The experiment was performed as described in the legend of panel A, but Y79 cells were used. WERI-Rb-1 cells (C) and Y79 cells (D) were treated with different concentrations of 4EGI-1 (3.125–100 μM), DMSO as solvent control or medium alone for 48 h. Cells were lysed and the amount of eIF4a in the cell lysate was analyzed by western blot. GAPDH was analyzed to verify equal loading. One representative experiment is shown. The quantification of three independent experiments (eIF4a/GAPDH) for WERI-Rb-1 cells and two independent experiments for Y70 cells is shown as a bar chart (mean ± SEM) below the western blots E–F) WERI-Rb-1 cells (C) and Y79 cells (D) were treated with different concentrations of 4EGI-1 (3.125–100 μM), DMSO as solvent control or medium alone for 72 h. Cells were lysed and the amount of eIF4a in the cell lysate was analyzed by western blot. GAPDH was analyzed to verify equal loading. One representative experiment is shown. The quantification of three independent experiments (eIF4a/ GAPDH) is shown as a bar chart (mean ± SEM) below the western blots. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA following Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Here, all conditions were compared to the cells treated with DMSO only

In order not to rely on a single time point, we repeated these experiments with both cell lines and treated them for 48 h and 72 h with 4EGI-1. However, as for the incubation for 24 h, we did not observe any significant differences in the amount of eIF4a in WERI-Rb-1 and Y79 cells (Fig. 2C–F). We concluded from these data that WERI-Rb-1 and Y79 express eIF4a at detectable amounts and that these do not change when the cells are treated with the inhibitor 4EGI-1 for up to 72 h.

Expression of eIF4e in two retinoblastoma cell lines under treatment with 4EGI-1

Having established that eIF4a is expressed in both reti-noblastoma cell lines, we sought to investigate whether this might also be the case for eIF4e. We used a similar experimental setup for this and cultured both WERI-Rb-1 and Y79 cells for 24 h with different amounts of 4EGI-1 (3.125–100 µM, respectively) and either with the same amount of DMSO as solvent control or with medium alone. After harvesting we lysed the cells and determined the amount of eIF4e in the cell lysate via western blot. We could detect eIF4e in both WERI-Rb-1 (Fig. 3A) and Y79 cells (Fig. 3B). When we quantified the amount of eIF4e in replicate experiments via densitometry, we observed no influence of treatment with 4EGI-1 on the amount of eIF4e in both cell lines after treatment for 24 h (Fig. 3A, B). We then performed the same experiment, but increased the incubation time with the inhibitor 4EGI-1 to 48 h and 72 h. As we have seen for eIF4a, prolonged treatment of both cell lines with 4EGI-1 also did not significantly alter the amount of eIF4e in the cell lysates (Fig. 3C–F). We concluded from these results that the eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4e is also expressed in the two retinoblastoma cell lines and that the amount of protein is independent of the concentration and the duration of the treatment with 4EGI-1.

Figure 3

Expression of eIF4e in two retinoblastoma cell lines under treatment with 4EGI-1. A) WERI-Rb-1 cells were treated with different concentrations of 4EGI-1 (3.125–100 μM), DMSO as solvent control or medium alone for 24 h. Cells were lysed and the amount of eIF4e in the cell lysate was analyzed by western blot. GAPDH was analyzed to verify equal loading. One representative experiment is shown. The quantification of three independent experiments (eIF4e/GAPDH) is shown as a bar chart (mean ± SEM) below the western blots. B) The experiment was performed as described in the legend of panel A, but Y79 cells were used. WERI-Rb-1 cells (C) and Y79 cells (D) were treated with different concentrations of 4EGI-1 (3.125–100 μM), DMSO as solvent control or medium alone for 48 h. Cells were lysed and the amount of eIF4e in the cell lysate was analyzed by western blot. GAPDH was analyzed to verify equal loading. One representative experiment is shown. The quantification of three independent experiments (eIF4e/GAPDH) for WERI-Rb-1 cells and two independent experiments for Y70 cells is shown as a bar chart (mean ± SEM) below the western blots WERI-Rb-1 cells (E) and Y79 cells (F) were treated with different concentrations of 4EGI-1 (3.125–100 μM), DMSO as solvent control or medium alone for 72 h. Cells were lysed and the amount of eIF4e in the cell lysate was analyzed by western blot. GAPDH was analyzed to verify equal loading. One representative experiment is shown. The quantification of three independent experiments (eIF4e/GAPDH) is shown as a bar chart (mean ± SEM) below the western blots. Please note that eIF4a and eIF4e in panels C, E, and F of Figures 2 and 3 were detected on the same membranes, respectively, and therefore share the GAPDH loading controls. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA following Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Here, all conditions were compared to the cells treated with DMSO only

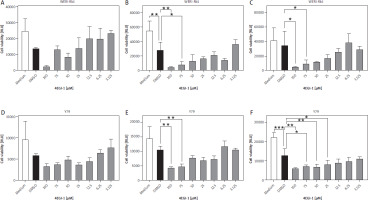

Treatment with 4EGI-1 reduces cell viability of WERI-Rb-1 and Y79 cells

Having established that both eIF4a and eIF4e are expressed in the two retinoblastoma cell lines, we sought to investigate whether the inhibitor 4EGI-1 might be able to influence the viability of WERI-Rb-1 and Y79 cells, which would imply that increased expression of eukaryotic initiation factors might represent a possible therapeutic target. For this, we seeded equal numbers of WERI-Rb-1 cells and added different amounts of 4EGI-1 (3.125–100 µM, respectively) and either the same amount of DMSO as solvent control or medium alone. We determined the cell viability 24 h later, but did not detect any significant differences between the DMSO-treated cells and the cells incubated with the different amounts of 4EGI-1 (Fig. 4A). When we increased the time of incubation to 48 h and 72 h, we observed a dose-dependent reduction of cell viability of the cells treated with 4EGI-1, and a significant difference between DMSO-treated cells and cells treated with 100 µM or 75 µM 4EGI-1 (Fig. 4B, C).

Figure 4

Treatment with 4EGI-1 reduces cell viability of WERI-Rb-1 and Y79 cells. A–C) WERI-Rb-1 cells were seeded into 96 well plates and treated with different concentrations of 4EGI-1 (3.125–100 μM), DMSO as solvent control or medium alone for (A) 24 h, (B) 48 h or (C) 72 h. Cell viability was determined as described in Materials and methods. Cell viability is shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3); one experiment from three with similar outcome is shown. D–F) The experiment was performed as described above, but Y79 cells were used. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA following Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. All conditions were compared to the cells treated with DMSO only. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

In order not to rely on a single cell line, we also repeated this experiment with Y79 cells. As with the WERI-Rb-1 cells, we detected no statistically significant differences between DMSO- and 4EGI-1-treated cells at the 24 h time point (Fig. 4D). Incubation with the inhibitor for 48 h resulted in a significant difference between DMSO-treated cells and cells treated with either 100 µM or 75 µM 4EGI-1 (Fig. 4E). After 72 h, we noted a significant difference additionally for the concentrations of 50 µM and 25 µM 4EGI-1 (Fig. 4F). In conclusion, our results indicate that inhibition of the association between eIF4e and eIF4g through 4EGI-1 reduces the viability of retinoblastoma cells, suggesting a possible therapeutic avenue that could be used for cancer therapy in the future.

Discussion

Retinoblastoma is a malignant, intraocular tumor which develops mostly within the first three years of life. The overall prognosis for the patient is variable and depends on several factors, most importantly the time of dia-gnosis [1]. Current treatment regimens include cryo-, thermo-, and brachytherapy, by which complete remission of the tumor and preservation of the patient’s eyesight can be achieved [4]. However, this requires a timely diagnosis of the tumor, which cannot be ensured in all cases. Thus, further treatment options to eradicate retinoblastoma cells are needed.

Eukaryotic initiation factors (eIFs) are proteins crucially involved in gene expression and especially mRNA translation [23]. Because all cells express proteins and perform translation of mRNAs into proteins, the inhibition of individual eIFs is a challenging task, as these proteins are required for normal functioning of non-tumor cells. A therapeutic possibility stems from the fact that the overexpression of individual eIFs has been reported in several cancer entities, making it imaginable that careful dosing of eIF inhibitors might target cancer cells while sparing eIFs in non-cancer cells. Indeed, inhibitors with different molecular mechanisms have been developed that target individual eIFs. Increased amounts of eIF4a have been reported, e.g. in hepatocellular carcinoma [12]. In this study, the expression of eIF4a in retinoblastoma was found to be significantly higher than in other ocular diseases such as phthisis bulbi and retinal detachment. Intriguingly, we also found high expression of eIF4a in uveal melanoma, suggesting that overexpression of eIF4a might be a general phenomenon in tumors of the eye and not restricted to retinoblastoma.

The development of the eIF4a inhibitors hippuristanol [24], pateamine A, und silvestrol [25] has shown that at least in principle this eIF is a possible target for cancer therapy. All inhibitors have so far only been investigated in pre-clinical cellular and animal models, and silvestrol showed the lowest toxicity [26], in contrast to pateamine A, which is very toxic in vivo, probably due to the irreversible binding to its target protein [27, 28].

Like eIF4a, eIF4e is also overexpressed in several cancer entities, including tumor of the breast [29], lung [13], prostate [14], colon [30], liver [15], and cervix [31]. Importantly, higher expression of eIF4e is associated with a higher tumor stage and a worse prognosis for the patient [13, 32]. In this study, we found that eIF4e is also highly expressed in retinoblastoma and uveal melanoma. Whether other eIFs are also overexpressed in retinoblastoma remains to be investigated.

Inhibitors targeting eIF4e have already been in clinical development. Ribavirin, a substance that binds to eIF4e and thereby blocks the binding site used by the target mRNAs, showed promising results in a small study in patients with acute myeloid leukemia, including complete remission in some of the patients [33]. Ribavirin has also been tested on retinoblastoma cell lines in vitro, including the two used in the current study, and shown to block cell growth and induce apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner [34]. In our study, we used a different inhibitor of eIF4e, which blocks the association of eIF4e and eIF4g to the eIF4F complex, which is important for the initiation of translation [35, 36]. In line with the previous study using ribavirin, both WERI-Rb-1 and Y79 cells were sensitive to treatment with 4EGI-1, which reduced the cell viability of both cell lines in a time- and dose-dependent manner, suggesting that eIF4e might represent a valuable therapeutic target.

Our study has several limitations. We were only able to obtain a limited number of samples for the immunohistochemical analysis of eIF4a and eIF4e expression, in some groups only one or two samples. In clinical practice, samples of the retina are only collected after enucleation, which explains the low number of samples. Nevertheless, our data clearly show a high expression of both proteins in retinoblastoma. The functional experiments were only carried out in two independent cell lines, which do not reflect the full spectrum of genetic variation found in retinoblastoma, and more experiments with other retinoblastoma cell lines or primary cells or organoids are required to substantiate eIF4e as a therapeutic target.

Conclusions

Our data show high expression of eIF4a and eIF4e in retinoblastoma. Both proteins are also expressed in the two retinoblastoma cell lines WERI-Rb-1 and Y79, and inhibition of eIFs with the inhibitor 4EGI-1 reduced cell viability of both cancer cell lines in a dose- and time-dependent manner.