Introduction

The 2023 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes emphasize the importance of cardiac rehabilitation (CR) in reducing post-myocardial infarction (MI) complications. CR encompasses various aspects, including patient assessment, risk factor management, lifestyle counseling, and psychological support. One of the key elements of CR is the promotion of physical activity through exercise prescriptions and counseling [1].

Until recently, the predominant approach for CR was moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT), characterized by sustained exercise at a constant intensity of approximately 60–80% of the maximum heart rate (HR). Current studies, however, have underscored the benefits of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) as a viable and effective option [2]. HIIT comprises alternating periods of vigorous exercise performed at an intensity exceeding 80% of the maximum HR interspersed with passive or active recovery intervals. This approach makes it possible to achieve results comparable to those of MICT, despite a lower total exercise volume [3]. Although the results of studies published to date are promising, indicating a significant improvement in exercise capacity and no substantial differences in the occurrence of adverse events between HIIT and MICT, there is still a need to establish precise guidelines regarding the intensity, frequency, and duration of HIIT sessions to maximize the potential benefits of this intervention [4].

To bridge this knowledge gap, a comprehensive analysis was conducted on the existing body of research on HIIT implementation in CR for adults following MI. Specifically, evidence was examined to identify the applicability of various HIIT protocols in CR, assess the efficacy of HIIT-based CR compared to alternative training interventions, and establish guidelines for implementing HIIT in CR programs for adults who have recently experienced MI.

Methods

Owing to the dynamics of this topic, a rapid systematic review was conducted [5]. Although the protocol has not been registered, the guidelines for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) were implemented [6].

Included studies: (1) used a HIIT protocol incorporating repeated bouts of any exercise at high intensity (above the anaerobic threshold or critical power/velocity), interspersed with recovery intervals (active or passive) [7]; (2) involved adults (≥ 18 years) who underwent MI; and (3) randomized participants to a HIIT or comparison (no HIIT) group. Studies involving participants without a history of MI were excluded to better isolate the effects of HIIT protocols on patients after MI. Reviews, animal studies, in vitro studies, case reports/series, non-peer-reviewed publications, duplicated publications, studies in which outcome indicator data could not be extracted, and studies in languages other than English were also excluded.

Two databases, PubMed and Web of Science, were searched for relevant studies published up to January 20, 2025. The search strategy used on PubMed was: (“high aerobic intensity training” OR “high-intensity interval training” OR “high intensity intermittent exercise” OR sprint or “high intensity interval training” OR “intermittent exercise” OR “interval training” OR “interval exercise” or fartlek) and (“Myocardial infarction” OR “myocardial infarctions” OR “heart attack” OR “heart attacks” OR “acute coronary syndrome” OR “acute coronary syndromes”), and was slightly adapted for Web of Science but used the same terms. The reference lists of the included studies were also searched for additional sources.

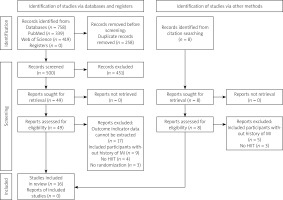

One reviewer searched for relevant studies. The flow chart illustrating this process is presented in Figure 1. First, duplicates were excluded. Following this, titles and abstracts were screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Those clearly relevant articles or those whose relevance was questionable were reviewed in the full text for inclusion or exclusion. Data on participants in the studies, HIIT and comparison protocols, and outcomes were extracted by one reviewer. Then qualitative data synthesis was done. The results are presented in terms of sample size, protocol comparison, and findings of significance.

Figure 1

The literature search and selection process. The original version of this PRISMA 2020 flow diagram is licensed under CC BY 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Source: Page MJ, et al. (2021) [6]

Results

A total of 758 titles and abstracts were identified during the search. Of these, 258 were duplicated and 500 titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility. After screening, 16 studies were included [8–23], accounting for 597 participants (n HIIT = 307; n comparison groups = 290) (Table I). Sources referring to the same population but with different outcome indicators were also included, but were not counted in the total number of participants, to prevent data duplication [8, 9, 11, 12, 14–16].

Table I

Description of included studies

| Study | Sample size (HIIT/ comparator) | HIIT Protocol | Comparator | Outcomes | Results and conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aispuru-Lanche et al. (2023) [8] | 28 (low-volume HIIT)/28 (high-volume HIIT)/24 (control) | Low-volume HIIT: < 10 min of high intensity (above second ventilatory threshold), with a total volume of 20 min, twice a week, for 16 weeks; high-volume HIIT: > 10 min of high intensity (above second ventilatory threshold), with gradually increasing total volume (20–40 min), twice a week, for 16 weeks | Unsupervised aerobic physical activity, for 16 weeks | Left ventricular echocardiographic parameters, serum biomarker levels | Both HIIT groups showed significant (p < 0.05) increases in left ventricular end-diastolic diameter and volume, and significant (p < 0.05) reductions of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide. Creatine kinase elevation was observed only in high-volume HIIT group (19.3%, p < 0.01) |

| Aispuru-Lanche et al. (2024) [9] | 28 (low-volume HIIT)/28 (high-volume HIIT)/24 (control) | Low-volume HIIT: < 10 min of high intensity (above second ventilatory threshold), with a total volume of 20 min, twice a week, for 16 weeks; high-volume HIIT: > 10 min of high intensity (above second ventilatory threshold), with gradually increasing total volume (20–40 min), twice a week, for 16 weeks | Unsupervised aerobic physical activity, for 16 weeks | Endothelial function, atherosclerosis, serum biomarker levels | There was a significant increase (p < 0.001) in brachial flow-mediated dilation, and significant decrease in carotid intima-media thickness on ultrasound (p = 0.019) and levels of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (p < 0.001) in both HIIT groups, with no significant changes in the control group |

| Choi et al. (2018) [10] | 23/21 | HIIT: 4 × 4 min (85–100% of maximal HR), each interval 3-minute recovery (50–60% of maximal HR), once or twice a week, for 9–10 weeks (18 sessions in total) | MICT: 28 min at 60–70% of maximal HR, once or twice a week, for 9–10 weeks (18 sessions in total) | Cardiovascular and functional states (including maximal VO2, and 6-minute walk test), psychological states (anxiety, depression, fatigue, insomnia) | Cardiovascular, functional, and some of the psychological (depression, fatigue) states were significantly (p < 0.05) improved in the HIIT group compared to the MICT group |

| Eser et al. (2021) [11] | 34/35 | HIIT: 4 × 4 min (RPE ≥ 15), each interval 3 min of active recovery, twice a week, and MICT: 30 min (RPE 13–14), once a week, for 9 weeks | MICT: 30 min (RPE 13–14), three times a week, for 9 weeks | Cardiac autonomic responses | There was an acute increase in HR during sleep after HIIT, but not after MICT. Chronic effects on resting HR and HR variability tended to be more beneficial after MICT than after HIIT |

| Eser et al. (2022) [12] | 31/30 | HIIT: 4 × 4 min (RPE ≥ 15), each interval: 3 min of active recovery, twice a week, and MICT: 30 min (RPE 13–14), once a week, for 9 weeks | MICT: 30 min (RPE 13–14), three times a week, for 9 weeks | Cardiorespiratory fitness (including peak VO2), left ventricular echocardiographic parameters, serum biomarker levels (high sensitivity troponin T, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide) | Cardiorespiratory fitness significantly improved in both groups. There was no group and time interaction for serum biomarker levels and left ventricular end-diastolic volume index at the end of the intervention (p > 0.05). After 1 year of follow-up, the left ventricular global longitudinal strain worsened in the HIIT group |

| Heber et al. (2023) [13] | 27/33 | HIIT: 1-minute intervals at 100% of maximum power output, each interval 1-minute recovery at 20% of maximum power output, with a total time of 20–30 min, twice a week for 12 weeks MICT: 60% of maximum power output for 20–30 min, twice a week for 12 weeks | MICT: 60% of maximum power output for 20–30 min, 4 times a week for 12 weeks | Cardiorespiratory fitness (including maximal VO2), cardiac autonomic responses, blood lactate concentration at maximum power output | Maximal VO2 increased to a greater extent in the HIIT group than in the control group. Maximal HR was not affected by training. Both training strategies were equally effective in reducing blood lactate levels |

| Jayo-Montoya et al. (2019) [14] | 21 (low-volume HIIT)/23 (high-volume HIIT)/11 (control) | Low-volume HIIT: < 10 min of high intensity (above second ventilatory threshold), with a total volume of 20 min, twice a week, for 16 weeks; high-volume HIIT: > 10 min of high intensity (above second ventilatory threshold), with gradually increasing total volume (20–40 min), twice a week, for 16 weeks | Unsupervised aerobic physical activity, for 16 weeks | Cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition | No significant changes were noted in the control group and between both HIIT groups in any of the studied variables. Reductions in waist circumference and improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness were observed only in the HIIT groups |

| Jayo-Montoya et al. (2021) [15] | 21 (low-volume HIIT)/23 (high-volume HIIT)/11 (control) | Low-volume HIIT: < 10 min of high intensity (above second ventilatory threshold), with a total volume of 20 min, twice a week, for 16 weeks; High-volume HIIT: > 10 min of high intensity (above second ventilatory threshold), with gradually increasing total volume (20–40 min), twice a week, for 16 weeks | Unsupervised aerobic physical activity, for 16 weeks | Cardiac autonomic responses | After intervention, no significant between HIIT group differences were observed. The peak HR and HR recovery significantly (p < 0.05) increased in both HIIT groups, but the HR reserve increased only in the high-volume HIIT group. The peak HR slightly decreased in the control group |

| Jayo-Montoya et al. (2022) [16] | 27 (low-volume HIIT)/26 (high-volume HIIT)/24 (control) | Low-volume HIIT: < 10 min of high intensity (above second ventilatory threshold), with a total volume of 20 min, twice a week, for 16 weeks; high-volume HIIT: > 10 min of high intensity (above second ventilatory threshold), with gradually increasing total volume (20–40 min), twice a week, for 16 weeks | Unsupervised aerobic physical activity, for 16 weeks | Quality of life, psychological states (including anxiety and depression), adherence to Mediterranean diet, physical activity and sedentary behavior levels | Both HIIT exercise interventions with Mediterranean diet recommendations significantly (p < 0.05) improved quality of life, along with reduced anxiety and depression symptoms. Better mental health was related to higher levels of physical activity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet |

| Kim et al. (2015) [17] | 14/14 | HIIT: 4 × 4 min (85–95% of maximal HR), each interval 3-minute recovery (50–70% of maximal HR), 3 times a week, for 6 weeks | MICT: 25 min of continuous training (70–85% of maximal HR) 3 times a week, for 6 weeks | Cardiorespiratory fitness (peak VO2) | HIT is significantly more effective than MICT for improving peak VO2 (p = 0.021) |

| Marcin et al. (2021) [18] | 35/34 | HIIT: 4 × 4 min (RPE ≥ 15), each interval 3 min of active recovery, twice a week, and MICT: 30 min (RPE 13–14) once a week, for 9 weeks | MICT: 30 min (RPE 13–14), three times a week for 9 weeks | Cardiorespiratory fitness (peak VO2) | Both groups showed improved peak VO2 without significant between-group differences (p = 0.104) |

| Moholdt et al. (2011) [19] | 30/59 | HIIT: 4 × 4 min (85–95% of maximal HR), each interval 1-minute recovery (70% of maximal HR), twice a week, for 12 weeks | MICT: 60 min of aerobic exercises, twice a week for 12 weeks | Cardiorespiratory fitness (peak VO2), endothelial function, quality of life, cardiac autonomic responses, serum biomarker levels | Peak VO2 increased more in the HIIT group (p = 0.002). Endothelial function, serum adiponectin, and quality of life increased in both groups. Serum ferritin and resting HR decreased in both groups. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol increased only in the HIIT group |

| Nam et al. (2023) [20] | 30 (MIIT)/29 (HIIT)/32 (control) | HIIT: 4 × 4 min (85% of maximal VO2), each interval 3-minute recovery (60% of maximal VO2), twice a week, for 7 weeks; MIIT: 4 × 4 min (95–100% of maximal VO2), each interval 3-minute recovery (60% of maximal VO2), twice a week, for 7 weeks, preceded by an adaptation period consisting of moderate-intensity exercise 2 weeks prior to the start of HIIT | Unsupervised aerobic physical activity, for 9 weeks | Cardiovascular and functional states (including maximal VO2, and 6-minute walk test), quality of life, psychological states (depression, fatigue, insomnia) | The control, MIIT, and HIIT groups showed significant (p < 0.05) improvements in quality of life, cardiovascular, and functional states. The maximal VO2 and 6-minute walk test improved the most in the MIIT group and at least in the control group. A significant decrease in depression was observed only in the HIIT group. No significant interaction between time and group was observed for other psychological states |

| Trachsel et al. (2019) [21] | 9/10 | HIIT: 2–3 × 6–8 min (RPE: 15), each interval 5 min of recovery (RPE: 5), twice a week, for 12 weeks | MICT: Unsupervised 30–60-minute continuous training (RPE 12–14), 5–7 days per week, for 12 weeks | Cardiorespiratory fitness (including peak VO2), echocardiographic parameters, serum biomarker levels (including N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide) | Cardiorespiratory fitness improved significantly (p < 0.05) in the HIIT group. HIIT also improved radial strain and pulsed-wave tissue Doppler imaging derived e’. There was no change in serum biomarker levels in both groups |

| Wisløff et al. (2007) [22] | 9/18 | HIIT: 4 × 4 min (90–95% of maximal HR), each interval 3-minute recovery (50–70% of maximal HR), 3 times a week, for 12 weeks | MICT: 47 min at 70–75% of maximal HR, 3 times a week, for 12 weeks. Recommended physical activity group: no protocol available | Cardiorespiratory fitness (including peak VO2), endothelial function, muscle biopsy, quality of life | Peak VO2 increased more in the HIIT group than the MICT group (p < 0.001). Improvement in endothelial function was greater in the HIIT group, and mitochondrial function in lateral vastus muscle increased only in the HIIT group. Quality of life significantly (p < 0.05) increased in both groups, but to a greater extent in the HIIT group (p < 0.02). No changes occurred in the group following recommended physical activity guidelines |

| Yakut et al. (2021) [23] | 11/10 | HIIT: 4 × 4 min (RPE 15–18), each interval 3-minute recovery (RPE < 14), twice a week, for 12 weeks | MICT: 20–45 min (RPE 12–14), twice a week, for 12 weeks | Functional capacity, cardiac autonomic responses, pulmonary function, strength, body composition, quality of life | Functional capacity, pulmonary function, respiratory peripheral muscle strength, and quality of life were significantly (p < 0.05) improved in both groups. The resting blood pressure, resting HR, body fat percentage, and body mass index significantly decreased in both groups. HIIT was more effective than MICT in improving pulmonary function and lower-extremity muscle strength |

The included studies described the effects of HIIT on echocardiographic parameters, serum biomarker levels, endothelial function, cardiac autonomic responses, cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, psychological states, and quality of life in adults who had undergone MI [8–23]. Of these, six compared different HIIT protocols with each other [8, 9, 14–16, 20], nine compared HIIT with a supervised MICT-based plan [10–13, 17–19, 22, 23], and eight compared HIIT with a mixture of exercise and recreational activities (i.e., placebo) [8, 9, 10, 13–16, 20–22]. Most researchers monitored HIIT intensities according to HR responses [8–10, 14–17, 19, 22] and self-tailored assessments using the 6-20 Borg scale [11, 12, 18, 21, 23]. Single studies have assessed exercise intensity through maximum power output [13] and maximal oxygen uptake (VO2) [20].

Most of the included studies found that HIIT interventions produced statistically significant (p < 0.05) improvements in psychological states and quality of life [10, 16, 19, 20, 22, 23], cardiovascular and functional states [10, 12–14, 17–23], cardiac autonomic responses [15, 23], echocardiographic parameters [8, 21], serum biomarker levels [8, 9, 19], and endothelial function [9, 19, 22] from pre- to post-intervention. A study by Marcin et al. (2021) [18] showed a significant effect of time (p < 0.001), with no differences between the groups depending on peak VO2 (p = 0.104). Eser et al. (2021) [11] reported that chronic effects on autonomic responses tended to be more beneficial after MICT than after HIIT. It was also found that there was no group and time interaction for the left ventricular end-diastolic volume index at the end of the intervention (p = 0.557). However, after 1 year of follow-up, the left ventricular global longitudinal strain worsened in the HIIT group [12].

Discussion

The implementation of HIIT for CR among patients recovering from MI demonstrates potential, albeit controversial, for improving outcomes. Heterogeneity in safety and utility, especially in early recovery, should be further explored when there is accumulating evidence of the advantages of HIIT. The findings from this rapid systematic review suggest that HIIT interventions offer superior improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness compared to MICT-based rehabilitation programs [10, 13, 14, 17, 19–22]. Evidence supports this statement in both cardiac and other patient groups [24–27]. HIIT has been shown to enhance angiogenesis, myocardial perfusion, and mitochondrial efficiency, which contribute to its efficacy in CR [28–31]. However, its use within the first week after MI remains contentious [12, 21, 32]. Patients in this period often demonstrate unstable cardiac profiles, including compromised ventricular function and heightened arrhythmia risk, making them not the best candidates for very intense exercise [33, 34]. Moreover, research has shown that beneficial metabolic adaptations associated with the implementation of HIIT become more remarkable after 6 weeks of regular exercise, following an initial period of impaired β-oxidation [35, 36]. Early application of HIIT may not provide sufficient time for these physiological changes to occur, thereby limiting its potential effectiveness in the early rehabilitation phases.

Beyond improving physiological benefits, the research found in this systematic review also suggests that HIIT leads to significant improvements in quality of life and psychological states, such as a decrease in depressive symptoms and fatigue [10, 16, 19, 20, 22, 23]. These findings raise the debate, as some meta-analyses found no statistically significant differences in quality of life between the HIIT and MICT groups, while others indicated that HIIT might provide particular benefits in terms of social functioning and vitality [37, 38]. For instance, a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Yu et al. (2023) [38] confirmed that while the overall quality of life scores of patients with cardiovascular disease did not differ significantly between HIIT and MICT, HIIT was associated with superior outcomes in self-perceived physical functioning and social engagement, particularly in individuals with coronary artery disease. These findings suggest that the variability and structure of HIIT, as opposed to the monotonous repetition of continuous training, may be responsible for greater patient participation and compliance. Psychological benefits, combined with time savings, may enhance motivation and reduce participation barriers, ultimately leading to enhanced long-term adherence to rehabilitation regimens.

Various HIIT protocols deserve attention. Five studies included in this review examined low-volume HIIT, characterized by short training sessions consisting of less than 10 min of vigorous activity [8, 9, 14–16]. Although it was investigated on a small participant group, the results suggest that low-volume HIIT might be comparable to its high-volume counterpart in improving cardiac and endothelial function, as well as quality of life and psychological states. This may be a key factor for those who cannot afford to spend much time engaging in physical activity, which may motivate them to exercise regularly. In addition, beginning with a reduced number of training sessions and employing shorter intervals allows the body to adapt gradually before increasing the overall exercise volume. In contrast, Nam et al. (2023) [20] found that it was possible to obtain even more pronounced beneficial effects by performing interval training at intensities of 100% of maximal VO2. This approach, however, may not be feasible in all patients who have recently undergone MI because of the high risk of hemodynamic instability. Therefore, MICT appears to be a safer predecessor of interval-based protocols with attributable cardiovascular effects [11, 18]. Hence, assessment of the time, frequency, and intensity of intervals and stratification of individuals is important. The investigation of hybrid strategies of initial low-intensity exercise followed by gradual incorporation of HIIT may be the most suitable modality, particularly during the initial period of post-MI recovery.

Although the trials included in this review appeared to confirm the efficacy of HIIT, several limitations warrant consideration. While this rapid systematic review adhered to the PRISMA guidelines, certain methodological constraints, including limited database searching and exclusion of non-English language sources, may have resulted in incomplete literature coverage and influenced the comprehensiveness of this review. Employing a single reviewer could also have potentially introduced bias in the selection process during both the screening of studies and the extraction of data. The engagement of a team comprising multiple reviewers for these tasks would likely enhance the reliability of the findings. Moreover, the heterogeneity of HIIT protocols across the included studies complicates the formulation of definitive conclusions. Variations in intensity, frequency, and interval duration impede the standardization of clinical practice recommendations. Furthermore, the included studies exhibited disparities in exercise intensity definitions and employed diverse monitoring methods, such as heart rate responses or the Borg scale, which hindered direct comparisons.

Conclusions

Based on the above considerations, larger multicenter randomized controlled trials with standardized HIIT protocols and longer follow-up periods are needed to gain a clearer understanding of the safety and long-term benefits of HIIT in post-MI rehabilitation. Furthermore, research that employs individualized risk stratification and combines low-intensity exercise with progressive HIIT could shed light on how to tailor protocols for diverse groups of patients.

From a clinical point of view, HIIT may serve as a time-efficient alternative to traditional CR, especially in patients who are clinically stable and highly motivated. HIIT protocols should be adapted to the patient group to implement incremental but cumulative progression of exercise intensity. In addition, the integration of psychological testing within rehabilitation programs would be capable of identifying those most in need of the psychological effects of HIIT, including diminished fatigue and depression.

With proper patient selection and protocol modification, HIIT may be an important component of CR with a time-effective strategy for efficient recovery following MI.