Summary

Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) patients with hyponatremia have specific clinical characteristics. Hyponatremia, identified in every seventh TTS patient on admission, was associated with higher long-term mortality and attenuated in-hospital improvement of left ventricular ejection fraction. For clinicians, it is important to consider electrolyte imbalance when assessing a patient’s prognosis and possibly adjusting a treatment regimen. Further studies are needed to explain the mechanism of unfavorable clinical outcomes in TTS patients with hyponatremia.

Introduction

Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) is an acute, potentially reversible cardiomyopathy characterized by transient left ventricular dysfunction [1, 2]. The clinical phenotype of TTS may closely mimic acute coronary syndrome (ACS) with stenocardia, ischemic changes in electrocardiography, and elevated cardiac biomarkers. However, the regional contractility abnormalities usually extend beyond a single coronary artery distribution despite the absence of obstructive coronary lesions in epicardial arteries [1–4]. In accordance with current data, TTS is observed in 1–2% of patients with suspected ACS, especially in the group of postmenopausal elderly women [5].

TTS onset is usually triggered by emotional, physical, or combined stressors, but in some cases, there is no evident trigger. The precise mechanism of TTS remains unclear, but most of the evidence indicates sympathetic stimulation and elevated levels of catecholamines as the most important factors. Another potential trigger may be hyponatremia. In accordance with current data, hyponatremia occurs when the serum sodium concentration declines below 135 mmol/l, and severe hyponatremia occurs below 125 mmol/l [6–8]. Clinically significant hyponatremia may appear in many conditions such as dehydration and fluid loss, volume overload, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, psychogenic polydipsia, hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, renal failure or subarachnoid hemorrhage [9]. Hyponatremia has been considered to be an important marker of poor prognosis in various clinical settings including heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, and many other conditions [9]. In the literature, there are various case reports of TTS induced by hyponatremia. In addition, a review summarizing previous case reports of the association between hyponatremia and TTS has been recently published [10]. The precise mechanism of TTS in hyponatremia has not been established yet. One hypothesis suggests a neurological dysfunction secondary to the hyponatremia as the trigger of catecholamine release followed by TTS [11, 12]. Alternative mechanisms may include the alteration of sodium-calcium pumps in myocyte membranes causing intracellular calcium overload [13]. Other data suggest that cell swelling secondary to the hyponatremia may result in myocyte damage. However, the influence of this electrolyte disorder on the course of TTS and clinical prognosis remains unknown.

Aim

In this study, we sought to investigate whether hyponatremia identified in TTS patients influenced in-hospital left ventricular ejection fraction recovery and long-term mortality in this group of patients.

Material and methods

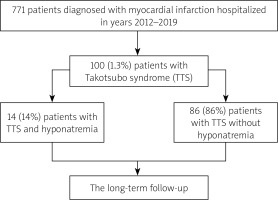

In this retrospective observational study conducted at a tertiary referral hospital between 2012 and 2019, TTS was diagnosed in 100 out of 7771 (1.3%) patients with acute myocardial infarction (Figure 1) [14]. The TTS diagnosis was based on typical echocardiography or left ventricular angiography images as well as the InterTAK Diagnostic Score [3]. Based on the blood sodium levels on admission, two separate groups were distinguished. Patients with a sodium level below 135 mmol/l were categorized as the hyponatremic group, and the remainder as patients without hyponatremia [7, 8]. Sodium level at discharge was also analyzed.

Patients’ characteristics including demography, anthropometric measurements, cardiovascular risk factors, existing comorbidities, and concomitant medications were gathered. Based on the ECG recorded on admission, patients were divided into those with ST-segment elevation of at least 1 mm in at least two contiguous leads and patients without ST-segment elevation. The patients with ST-segment elevations present on the ECG underwent coronary angiography immediately after admission. Myocardial necrosis markers, including isoenzyme MB of creatine kinase (IU/l, upper limit of normal of 24 IU/l) and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (ng/ml, upper limit of normal: 0.014 ng/ml) were estimated at baseline and at least twice within the first 24 h. Their peak values during the hospitalization were also analyzed. Renal failure was defined by the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) lower than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. The GFR was estimated with the Cockcroft-Gault formula. Detailed data regarding diuretic treatment were also collected. Anemia was identified when the hemoglobin level was < 13 g/dl for men and < 12 g/dl for women. The cut-off value for thrombocytopenia was 100 × 103/µl. The long-term all-cause mortality data were acquired from the Polish National Death Registry (Figure 1). The study protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the relevant local Ethics Committee (Consent No. 1072.6120.128.2023; date: 22 November 2023).

Coronary angiography

Coronary angiography was performed in all patients included in the study. Coronary angiograms were assessed independently in two contralateral projections for each artery by two invasive cardiologists unaware of the clinical characteristics of the patients. Coronary lesions exceeding 50% were defined as significant. All insignificant plaques were divided into two groups: those narrowing the coronary lumen by 0–30% and by 30–50%. Moreover, the coronary slow flow phenomenon was defined as thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) < 3 or corrected TIMI frame count (TFC) > 27 frames in at least one epicardial artery [14].

Echocardiography and left ventricular angiography

A two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography was performed at rest in a left decubitus position [15–17]. Images of adequate quality were acquired using a Vivid S5 ultrasound system (GE, Solingen, Germany) equipped with a multi-frequency harmonic transducer, 3Sc-RS (1.3-4 MHz). All estimations were conducted according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Echocardiography [17]. The left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was assessed with Simpson’s method on admission and repeatedly during hospitalization, usually between 3 and 7 days after admission. Left ventricular angiography was performed in 58 patients with a dedicated pigtail catheter in the left anterior oblique projection at the discretion of the operator [14]. Three main types of TTS – apical, midventricular, and basal – were used to classify patients in accordance with the current guidelines [3].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as medians (interquartile range) and categorical variables as numbers (percentage). Continuous variables were first checked for normality of distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences in continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test for normally distributed data or the Mann Whitney U-test for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were analyzed with the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. A Kaplan-Meier curve for overall mortality was constructed to estimate the survival rates, and a log-rank test with a Bonferroni-corrected threshold was performed to assess the differences in survival between the studied groups. Finally, all independent variables potentially associated with outcome were included in the Cox proportional hazard regression model to determine independent predictors of long-term all-cause mortality. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In the study group, 14 (14%) patients were identified with hyponatremia (Figure 1). Hyponatremic patients were significantly older than normonatremic patients (median age 78.5 vs. 69 years, p = 0.013). Both groups consisted mainly of women (85.7 and 89.5%, respectively) (Table I).

Table I

Clinical characteristics of TTS patients with and without hyponatremia

We did not identify significant differences in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and concomitant disorders between TTS patients with and without hyponatremia (Table I). The incidence of prior stroke was higher among hyponatremic TTS patients (7.1% vs. 0%, p = 0.046). Similarly, chronic heart failure was diagnosed more often in patients with TTS with hyponatremia than with normonatremia (50% vs. 12.8%, p = 0.001).

There was a significant difference in clinical presentation. ST-segment elevation was identified more often in hyponatremic TTS patients as compared with normonatremic TTS patients (78.6% vs. 48.8%, p = 0.033). On admission there was no difference in LVEF, but its improvement during hospitalization was higher in TTS patients without hyponatremia (10 [0–20] vs. 0 [0–5]%, p = 0.039). As a result, LVEF at discharge was higher in this group (50 [42–55] vs. 40 [35–45]%, p = 0.032). TTS patients with hyponatremia more often presented apical than midventricular type of TTS (100 vs. 81.4%, p = 0.021) than those with normonatremia. Among both groups, there were no patients with the basal type of TTS. No differences were also found in the type of TTS trigger. There were no differences in Killip class on admission, occurrence of cardiogenic shock, length of hospitalization, in-hospital mortality, or prescribed drugs at discharge.

Apart from lower sodium (132 [129–134] vs. 140 [138–142] mmol/l, p < 0.001) and hemoglobin (12.9 [12.1–13.6] vs. 13.8 [12.8–14.5] g/dl, p = 0.029) levels on admission, the remaining laboratory parameters were similar in TTS patients with hyponatremia versus normonatremia (Table II). Sodium levels at discharge were also lower in patients with hyponatremia at baseline (136 [132–142] vs. 141 [139–143] mmol/l, p = 0.001) as compared with normonatremic. However, there were 7 (7%) patients with hyponatremia at discharge.

Table II

Laboratory parameters in the analyzed groups

Long-term mortality and its independent predictors

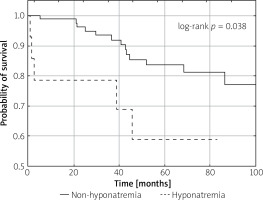

Within a median of 53 (31–82) months, significantly higher long-term all-cause mortality was observed in the hyponatremic as compared to normonatremic TTS subgroup. Among the 14 patients with TTS and hyponatremia, 5 deaths were identified, while 13 patients died in the TTS group without hyponatremia (log-rank p = 0.038) (Figure 2).

Patients who died were older (80.5 [72–85] vs. 67.5 [60.3–75] years, p < 0.001), more frequently with Killip class III/IV on admission (1.7% vs. 0.4%, p = 0.035), had a lower sodium level on admission (136.5 [134.3–140] vs. 140 [137.3–142] mmol/l, p = 0.015) and at discharge (138 [136–141] vs. 141 [140–143], p = 0.002), had a lower BMI (22.5 [20.3–24.9] vs. 25.9 [23.5–30.1] kg/m2, p = 0.017), higher creatinine concentration (99 [70–113] vs. 74 [64–84] µmol/l, p = 0.003), lower LVEF on admission (33 [26–35] vs. 40 [31–45]%, p = 0.016) and at discharge (40 [35–45] vs. 50 [43–55]%, p = 0.005), and had higher baseline CRP (16.0 [7.0–33.8] vs. 4.0 [1.9–8.5] mg/l, p = 0.007) than those who survived. Before inclusion in the multivariable model, significant associations between independent variables were identified. Sodium on admission was correlated with hemoglobin level (R = 0.280, p = 0.005), LVEF at discharge (R = 0.264, p = 0.019), and sodium at discharge (R = 0.507, p < 0.001), while the latter was inversely correlated with patient’s age (R = –0.219, p = 0.029). Patient’s age moreover was correlated with creatinine concentration (R = 0.349, p < 0.001) and inversely correlated with hemoglobin level (R = –0.254, p = 0.011).

The Cox proportional hazard regression analysis showed that the patient’s age, lower baseline sodium level, higher creatinine concentration, and Killip class III/IV on admission were independently associated with higher long-term mortality (Table III).

Table III

Independent predictors of long-term mortality

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that hyponatremia is independently associated with increased long-term mortality in patients with a diagnosis of TTS. Moreover, we found differences in baseline clinical characteristics between TTS patients with hyponatremia and normal sodium levels. We also observed a negative impact of sodium level below 135 mmol/l as measured on admission on LVEF improvement during index hospitalization.

In a review of case reports of TTS patients with hyponatremia, Yalta et al. found hyponatremia to be a negative prognostic factor, regardless of being a trigger or a result [10]. The negative prognostic significance of hyponatremia is also well proven in other diseases. In a large cohort study on 279 508 acutely hospitalized patients by Holland-Bill et al., hyponatremia was shown to be an unfavorable predictor of both short- and long-term mortality regardless of underlying disease [18]. Electrolyte disturbances are a common concern in patients suffering from heart failure and manifest not only as hyponatremia but also as hypochloremia and hypokalemia, all resulting in worse survival and longer hospitalization [19]. Heart failure is considered the most common cause of hypervolemic hyponatremia as a result of increased release of antidiuretic hormone and restricted renal blood flow [20]. In a study by Lu et al., hyponatremic patients with heart failure had worse outcomes; the 90-day mortality rate in participants with low sodium levels was 19.4 vs. 6.3% in normonatremic patients, and after 4 years it was 50.8% vs. 39.1%, respectively [21]. Regarding acute myocardial infarction, Cordova Sanchez et al. observed increased 30-day mortality (2.7 vs. 2.2%) as well as a larger decline of the LVEF (50.7 vs. 28.9%) in this group of patients [22]. Similarly, in a long-term observational study of STEMI patients by Lazzeri et al., 21.9% of those with hyponatremia died, compared to 13.5% of those without hyponatremia [23]. Moreover, similar results were also obtained by Choi et al., who observed higher mortality in participants with lower sodium levels both on admission and at discharge [24].

Hyponatremia can occur in both hypotonic and non-hypotonic forms, whereas the hypotonic one is clinically most important and may present as hypovolemic, euvolemic, or hypervolemic [6, 8]. In recent reports summarized by Yalta et al., hyponatremia, as the primary trigger of TTS, has various clinical causes such as the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), diuretic use, polydipsia, vomiting, chronic alcoholism, and dietary restriction [10]. In the analysis of the association between TTS and hyponatremia, it is usually not clear which factor occurred first. Hyponatremia may be an effect of TTS, but it may also be its cause [10].

The response to emotional or physical stress typical for TTS activates adrenergic discharge, which may, through substances such as norepinephrine, lead to the release of ADH and copeptin, resulting in lower sodium levels [25]. In addition, ADH can lead directly to myocardial dysfunction with coronary vasoconstriction and an increase in phosphorylase activity [26]. Circulating catecholamines act peripherally by affecting membrane ion exchangers, which may also contribute to hyponatremia [27].

In the opposite hypothesis, sodium depletion may lead to central nervous system dysfunction, resulting in the release of catecholamines and the development of TTS [10]. Hyponatremia impacts the myocardium directly by altering the action of the sodium-calcium pump in cardiomyocytes, which leads to calcium overload and may induce myocardial edema, contractile dysfunction, and coronary vasoconstriction [28, 29]. In accordance with this, the majority of documented cases featuring hyponatremia-induced TTS revealed LVEF < 50% at TTS onset [10]. This observation may also explain the unrestricted wall motion abnormalities in the context of TTS induced by hyponatremia. Another significant mechanism is oxidative stress, which is increased by electrolyte disorders and predisposes to TTS development [10]. As demonstrated previously in experimental studies conducted on rats, the occurrence of cardiomyopathy and exacerbation of ischemia-reperfusion injury is linked to oxidative stress and calcium overload induced by hyponatremia [30–32].

In our study, 58 out of 100 patients had an undetermined TTS trigger. While this may suggest a possible secondary form of TTS, no acute conditions such as infections or neurological disorders were identified in these patients [33]. Current evidence indicates that secondary TTS, typically linked to physical stressors or organic diseases, often leads to more severe left ventricular dysfunction and worse outcomes [34]. However, in our study, the presence of an undetermined trigger was not associated with worse short- or long-term outcomes. Recent findings highlight the role of genetic factors in the development and progression of TTS [33]. This emphasizes the need for further research to clarify the role of undetermined triggers and genetic factors in shaping TTS prognosis.

Our study has several limitations. First, patients’ data were derived from a single-center registry and only a limited number of TTS patients who had few unadjudicated clinical events during follow-up. Therefore, the study findings should be interpreted with caution and larger scale studies should be conducted to validate our findings. Second, only half of the hyponatremic TTS patients still demonstrated lower sodium levels at discharge, and there is no information on whether hyponatremia was only a short-term event or a chronic state in the other half. More precise data regarding the duration of hyponatremia would be valuable. Third, microvascular perfusion was evaluated solely by coronary angiography, with a lack of cardiac magnetic resonance or invasive assessment of microvascular function. However, the applied angiographic scales are well-validated and approved methods in the setting of TTS [14]. Additionally, due to the retrospective nature of the registry, we were unable to conduct a detailed analysis of mechanisms of hyponatremia, its treatment methods, volemic status, and the causes of death. We recognize that patients with hyponatremia had an inherently greater baseline risk, including older age, and more frequent history of stroke and chronic heart failure, which may confound the study findings. Due to the lack of complete information on the doses of diuretics administered prior to hospital admission, we cannot exclude that this was the cause of hyponatremia in at least part of the study group. Further studies with adjudicated causes of death and adjustment for baseline characteristics are necessary to better understand the role of hyponatremia in the prognosis of TTS patients.

Conclusions

TTS patients with hyponatremia have specific clinical characteristics. Hyponatremia, identified in every seventh TTS patient on admission, was associated with higher long-term mortality and attenuated in-hospital improvement of LVEF. Further studies are needed to explain the mechanism of unfavorable clinical outcomes in TTS patients with hyponatremia.