Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM), classified as grade IV diffuse astrocytic tumour by the World Health Organisation, represents the most aggressive and prevalent form of primary malignant brain tumours in adults, with a median survival of less than 15 months despite maximal therapy [1, 2]. The annual incidence of GBM is approximately 3–4 cases per 100,000 people in Western countries, but epidemiological data for Central Asia remain limited [3, 4]. Characterized by marked intratumoral heterogeneity, diffuse infiltration, and pronounced therapy resistance, GBM is a major challenge for neurooncology worldwide [5–7].

Mounting evidence highlights the central role of the tumour microenvironment (TME) in GBM progression and treatment response [8]. The tumour microenvironment in GBM is distinguished by an extensive infiltration of immunosuppressive myeloid cells (e.g., tumour-associated macrophages), regulatory T-cells, dysfunctional lymphocytes, and a cytokine milieu that drives immunosuppression and tumour tolerance [9–11]. Cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1β, and interferon-γ (INF-γ) are key mediators of both local and systemic immune responses in GBM, and their serum levels have been associated with prognosis, tumour progression, and therapy resistance [12–15].

In particular, high IL-6 and IL-10 levels correlate with poor survival, while pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and INF-γ may play dual roles depending on tumour context [16–19]. Emerging studies also point to the prognostic value of systemic biochemical markers (liver function, electrolytes, iron status) and their interaction with immune profiles [20–22].

Sex-based biological differences are increasingly recognised in cancer incidence, immune responses, and outcomes [23, 24]. In GBM, males exhibit higher incidence and poorer survival than females, potentially reflecting sex-linked immune mechanisms, metabolic regulation, and genetic background [25–28]. Nonetheless, few studies have directly compared cytokine or metabolic marker profiles between female and male GBM patients, and none from Central Asia.

This study aims to (1) systematically characterize the serum cytokine and biochemical marker profiles in newly diagnosed GBM patients from Uzbekistan and (2) investigate potential sex-based differences, contributing novel data from a Central Asian cohort to the global understanding of GBM immunometabolism.

Material and methods

Study population and clinical data collection

This cross-sectional study included a total of 52 participants, comprising 26 patients with newly diagnosed GBM recruited from the Andijan regional branch of the Medical Centre of Oncology and Radiology, Uzbekistan, between 2024 and 2025, and 26 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. The glioblastoma group consisted of 18 females and 8 males, aged 9–79 years (mean age: 54.3 ±15.7 for females, 47.5 ±28.6 for males). Healthy controls included 18 females and 8 males with no history of neurological, oncological, or systemic inflammatory diseases.

All GBM diagnoses were confirmed histopathologically according to the World Health Organisation 2021 classification of central nervous system tumours. None of the patients had received prior oncological treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy) at the time of sample collection.

Comprehensive clinical data – including age, sex, clinical presentation, and radiological findings – were collected from medical records. All participants underwent standardized clinical assessment and venous blood sampling in the morning after overnight fasting. Serum was isolated by centrifugation and stored at –80°C until analysis.

Notably, the GBM group included only 8 male participants, which may limit statistical power for sex-stratified analyses, as fewer male GBM patients were available at the participating clinical centres during the study period.

Sample collection and biochemical analysis

Peripheral blood samples were collected prior to surgical resection or initiation of oncological therapy. Serum was isolated by centrifugation and stored at –80°C until analysis. Biochemical parameters including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (APDEA), total and direct bilirubin, calcium, magnesium, iron, uric acid, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), phosphorus, cholesterol, and creatinine were measured using HumaStar 100 (Germany), following standard laboratory procedures.

Cytokine measurements

Serum levels of IL-10, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and INF-γ were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (USCN, Cloud-Clone Corp., Wuhan, China), as per manufacturer’s instructions. Assays were run in duplicate and calibrated against standard curves. The detection limits were 0.5–2.0 pg/ml for all analytes. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were < 8% and < 10%, respectively, indicating high assay reproducibility.

Statistical analysis

All data were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) where appropriate. Sex-based differences were assessed with Student’s t-test (normally distributed) or Mann-Whitney U test (non-normal data). Correlation analysis (Spearman’s rho) and principal component analysis were performed to evaluate relationships among markers and overall variance. All statistical analyses were conducted using Python (SciPy, pandas, scikit-learn) and SPSS v26.0 (IBM Corp, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 26 patients with newly diagnosed GBM (18 females, 8 males; age range: 9–79 years) and 26 age- and sex-matched healthy controls (18 females, 8 males) were included in the study. The mean age for females in the GBM group was 54.3 ±15.7 years, while the mean age for males was 47.5 ±28.6 years. All participants underwent standardized clinical evaluation, and blood samples were collected prior to initiation of any oncological treatment. Serum cytokines (IL-10, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) and biochemical parameters (APDEA, ALT, AST, bilirubin, calcium, magnesium, iron, creatinine, uric acid, LDH, and phosphorus) were analysed using validated laboratory methods.

Cytokine profile by sex

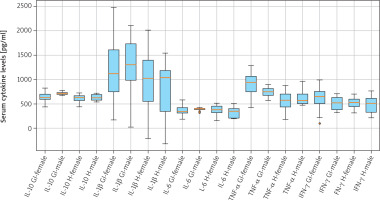

Comparison of serum cytokine concentrations between female (n = 18) and male (n = 8) GBM patients revealed no statistically significant differences for any measured analyte (Table 1).

Table 1

Serum cytokine levels by sex (mean ± standard deviation)

Mean IL-10 levels were 669.1 ±82.4 pg/ml in females and 687.9 ±74.5 pg/ml in males (t = –0.41, p = 0.687). IL-1β levels averaged 1043.0 ±712.2 pg/ml for females and 1032.0 ±778.5 pg/ml for males (t = 0.02, p = 0.981). Similarly, IL-6 concentrations were 411.1 ±126.4 pg/ml in females vs. 409.0 ±78.7 pg/ml in males (t = 0.03, p = 0.976). Tumor necrosis factor-α levels were 841.4 ±357.5 pg/ml in females and 691.3 ±170.5 pg/ml in males (t = 0.75, p = 0.463). INF-γ concentrations were 601.5 ±172.5 pg/ml and 532.4 ±207.0 pg/ml for females and males, respectively (t = 0.69, p = 0.498).

These findings indicate that systemic cytokine profiles are largely comparable between sexes in this GBM cohort (Table 1, Figure 1).

Biochemical parameters by sex

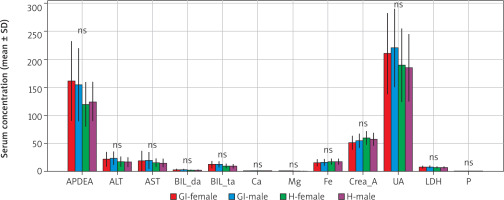

Similarly, analysis of routine biochemical parameters demonstrated no sex-based differences between female and male GBM patients (Table 2).

Table 2

Serum biochemical parameters by sex mean ± standard deviation

Alkaline phosphatase levels were 161.3 ±70.8 U/l in females and 155.0 ±65.0 U/l in males (t = 0.23, p = 0.819). Alanine aminotransferase activity averaged 22.2 ±13.4 U/l for females and 24.0 ±12.0 U/l for males (t = –0.30, p = 0.768). Aspartate aminotransferase activity was 18.9 ±18.6 U/l and 20.0 ±15.0 U/l in females and males, respectively (t = –0.16, p = 0.876). No significant sex-related differences were also found for bilirubin (direct and total), calcium, magnesium, iron, creatinine, uric acid, LDH, or phosphorus values (all p > 0.05).

Collectively, these results suggest that baseline biochemical homeostasis is preserved in GBM patients regardless of sex, and observed disease-associated changes are not sex-dependent (Table 2, Figure 2, 3).

Figure 2

Biochemical parameters by sex

ALT – alanine aminotransferase, APDEA – alkaline phosphatase, AST – aspartate aminotransferase, LDH – lactate dehydrogenase, UA – uric acid Boxplots showing interindividual variability in key biochemical parameters (APDEA, ALT, AST, UA, LDH) by sex in glioblastoma (GBM) patients and healthy controls. Boxes represent interquartile range, horizontal lines represent median, whiskers indicate range, and dots represent individual values. Gl-F-GBM female, Gl-M-GBM male, H-F-healthy female, H-M-healthy male.

Correlation and multivariate analyses

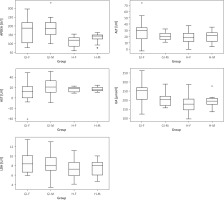

Analysis of biochemical markers across age groups

To evaluate potential age-related differences in systemic profiles, all participants (n = 52; 26 GBM [18 females, 8 males] and 26 healthy controls [18 females, 8 males]) were stratified into three age groups: < 40 years (n = 6), 40–60 years (n = 24), and > 60 years (n = 22).

One-way ANOVA showed no statistically significant differences for most cytokines and biochemical parameters across age categories (Table 3). Mean uric acid (UA) levels were significantly higher in the 40–60 years (220.3 µmol/l) and > 60 years (245.4 µmol/l) groups compared with participants younger than 40 years (160.5 µmol/l; F = 4.32, p = 0.029).

Table 3

Key analytes across age groups (ANOVA)

IL-10 levels showed a borderline age-related increase (F = 3.21, p = 0.048), whereas Fe demonstrated a non-significant upward trend in the oldest group (F = 2.88, p = 0.067). No age-related differences were observed for ALT, APDEA, Ca, or other analytes (p > 0.05).

Except for UA (significant) and IL-10 (borderline), all parameters remained stable across age groups, suggesting preserved biochemical homeostasis regardless of age.

Spearman correlation analysis

To explore interrelationships between inflammatory and metabolic parameters, a Spearman rank correlation analysis was performed across all participants (n = 52). Several significant positive associations (|ρ| ≥ 0.4, p < 0.05) were identified (Table 4).

Table 4

Spearman correlation matrix (significant)

Pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TNF-α, IFN-γ) were positively correlated with hepatic enzymes (ALT, AST) and purine metabolism markers (UA, Crea_A), while bilirubin indices were linked to Fe and LDH. These findings suggest coordinated inflammatory-metabolic shifts in GBM patients that are not present in healthy individuals.

Discussion

This study provides the first comprehensive evaluation of circulating cytokine and serum biochemical marker profiles in GBM patients from Uzbekistan, with explicit stratification by sex and age. Our results demonstrated no statistically significant sex-based differences in major immune mediators – including IL-10, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ – or in core biochemical parameters (APDEA, ALT, AST, bilirubin, calcium, magnesium, iron, creatinine, uric acid, LDH, and phosphorus), as all p values exceeded 0.05. Both female and male patients showed considerable intra-group variability, consistent with the well-documented molecular and clinical heterogeneity of GBM [1, 3, 5, 10, 13].

Importantly, age-related analysis revealed significantly higher UA levels in older patients, alongside a borderline increase in IL-10 with age, while other cytokines and biochemical markers remained stable across age groups. This finding aligns with previous reports linking hyperuricemia to increased tumour burden, metabolic turnover, and poorer outcomes in GBM [1, 2], and suggests that age-related metabolic alterations may amplify systemic purine metabolism without sex-specific effects.

Correlation analysis further underscored the close interplay between inflammatory and metabolic pathways in GBM. Significant positive correlations were observed between IL-10, TNF-α, and IFN-γ and key biochemical markers such as ALT, AST, UA, and LDH (Table 4). In addition, bilirubin indices (BIL_da and BIL_ta) were positively associated with iron and LDH, while creatinine correlated with UA. These relationships support the concept that GBM triggers a coordinated immunometabolic response, in which low-grade hepatic and oxidative stress accompany systemic inflammation. Such integrated shifts may reflect tumour-induced metabolic reprogramming, consistent with known activation of the STAT3 and IDO1 pathways that promote immunosuppression and metabolic rewiring in the GBM microenvironment [15, 16, 19].

The absence of sex-related differences in cytokine or biochemical levels in our cohort is in line with recent studies suggesting that the strongly immunosuppressive and metabolically reprogrammed TME characteristic of GBM can override subtle host- or sex-related variations in systemic biomarker profiles [9, 12, 15, 16, 20]. Both female and male GBM patients showed similarly elevated IL-6 and IL-10 – established indicators of GBM progression – without statistical difference between sexes. Our findings are broadly consistent with studies from European [23] and East Asian [9] cohorts, which also reported elevated IL-6 and IL-10 levels without significant sex-based differences. However, such comparative data from Central Asian populations have been largely lacking, underscoring the novelty and regional relevance of our dataset. This pattern suggests that tumour-intrinsic factors, rather than patient sex, predominantly shape the systemic cytokine milieu. While some studies have reported sex-based differences in immune responses or clinical outcomes in brain tumours [23–28], our findings indicate that sex is unlikely to be a major determinant of circulating cytokine or metabolic marker profiles in GBM.

Several limitations should be noted. First, the sample size – particularly among male patients – was relatively small, potentially limiting statistical power. Second, molecular stratification (e.g., IDH1 mutation, MGMT promoter methylation) was not performed in this study, which limits the biological interpretation of our findings. Future multicentre studies integrating molecular profiling are warranted to better understand the immunometabolic landscape of GBM [19, 20]. Third, the cross-sectional design precludes assessment of longitudinal trends or treatment-related dynamics. Future studies should include larger, multicentre cohorts with integrated molecular data and longitudinal follow-up to validate our findings and evaluate their clinical utility in patient stratification, prognosis, and therapy monitoring [27, 28].

In summary, our study highlights that GBM patients exhibit coordinated immunometabolic alterations characterized by elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines and interlinked changes in metabolic markers, yet these profiles are not influenced by sex. Instead, age-related increases in UA and strong correlations between inflammatory and metabolic parameters underscore the central role of tumour-driven metabolic reprogramming. These results suggest that GBM tumour biology exerts a stronger influence on systemic biomarker profiles than patient sex, and provide a valuable regional reference for neuro-oncology practice in Central Asia.

Conclusions

This study provides the first integrated assessment of circulating cytokines and serum biochemical markers in GBM patients from Uzbekistan, with explicit consideration of sex and age. Our results demonstrate that systemic cytokine and metabolic profiles do not differ significantly between female and male GBM patients, indicating that sex is unlikely to be a major determinant of immune or metabolic biomarker variation in this population.

Age-related analysis revealed significantly higher UA levels and a borderline increase in IL-10 in older patients, while other cytokines and biochemical markers remained stable across age groups. Furthermore, correlation analysis showed strong positive associations between pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TNF-α, IFN-γ) and key metabolic markers (ALT, AST, UA, LDH), highlighting a coordinated immunometabolic shift associated with GBM.

Collectively, these findings suggest that tumour-intrinsic factors and the GBM microenvironment exert a stronger influence on systemic immunometabolic profiles than patient sex, while age contributes to specific metabolic alterations (notably hyperuricemia). This work provides a valuable regional reference dataset and underscores the potential of combined cytokine-biochemical profiling as a tool for biomarker discovery, patient stratification, and therapy monitoring in GBM.