Introduction

Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) was first described in 1903 as a benign, non-infectious, localized lesion of the periocular region [1]. It was characterized by the proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, accompanied by chronic inflammatory infiltration by lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and mast cells [2]. In 1990, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMTs) were recognized as a distinct entity separate from the broader category of inflammatory pseudotumors [3].

IMTs are rare neoplasms with an intermediate degree of differentiation, exhibiting a recurrence rate of 25% but rarely metastasizing (2%) [4–6]. Today, IMTs and IPTs are recognized as distinct nosological entities [7]. IMTs are primarily located in the peritoneal cavity in 75% of cases, particularly in the mesentery, greater omentum, and retroperitoneum. They have also been sporadically reported in the head and neck region, bladder, prostate, testicles, female reproductive system, and central nervous system [8–10].

IMTs are usually solitary and predominantly affect children and young adults [9, 10]. Patients with IMTs generally present with systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, weakness, and malaise. However, the primary manifestations are local signs and symptoms related to the neoplastic mass, its swelling, reactive local inflammation, and anatomical location. For instance, IMTs of the larynx cause hoarseness, those of the trachea result in dyspnea and hemoptysis, gastrointestinal IMTs cause obstructive ileus or constipation, liver IMTs lead to jaundice and splenomegaly, and urinary system IMTs present with dysuria and hematuria. IMTs of the uterus can cause discomfort and uterine bleeding [11–13].

IMTs lead to increased markers of inflammation, such as elevated polymorphonuclears, C-reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Anemia, thrombocytosis, and hypergammaglobulinemia may also be observed. IMTs in the liver’s portal area can cause elevated levels of γ-glutamyl transferase (γGT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aspartate transaminase (SGOT), and alanine transaminase (ALT), indicating obstructive cholestasis [12, 13].

Pulmonary IMTs are rare and are primarily detected by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast. These tumors appear as heterogeneous or homogeneous masses characterized by hyper- or hypovascularity, with or without calcifications [14]. Pulmonary IMTs are more common in children and adolescents, typically located in the parenchyma and rarely in endobronchial locations. This paper provides a comprehensive review of the literature on this rare clinical entity, exploring its etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment.

Methods

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to gather information on IMTs of the lung and other anatomical sites. The primary databases used for the literature search included PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library. The search strategy was designed to identify relevant studies, reviews, and case reports related to IMTs. Keywords such as “inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor”, “IMT”, “pulmonary IMT”, “mesenchymal tumor”, “intermediate malignancy”, “myofibroblastic proliferation”, “rare lung tumor”, and “pediatric mesenchymal tumor” were used in various combinations, employing Boolean operators to refine the search results. Inclusion criteria for the review included studies and case reports published in peer-reviewed journals, articles discussing the clinical presentation, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of IMTs, and studies available in English. Exclusion criteria comprised non-peer-reviewed articles, studies not focused on IMTs or those that did not provide relevant clinical information, and articles not available in English (Figure 1).

Data from the selected articles were extracted and compiled into a standardized form, capturing author(s) and year of publication, study type (e.g., case report, review, clinical study), patient demographics (age, gender), anatomical location of the tumor, clinical presentation and symptoms, diagnostic methods used (imaging, histopathology, molecular techniques), treatment modalities and outcomes, and follow-up duration and recurrence rates. The quality of the included studies was assessed using standard criteria for evaluating clinical research, considering the robustness of the methodology, sample size, and the relevance of the findings to the topic of IMTs. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the findings, including recurrence rates, metastasis rates, and treatment outcomes where applicable, while a qualitative synthesis was conducted for case reports and studies lacking numerical data. As this study involved a review of existing literature, no ethical approval was required, but the review adhered to ethical standards for reporting and conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Discussion

Multiple primary cancers and IMTs

Multiple primary cancers were first defined by Warren and Gates in 1932 [15]. The diagnostic criteria include: (i) the presence of at least two tumors confirmed as malignant in a single patient, (ii) histological documentation of malignancy, and (iii) definitive exclusion of one malignancy being a metastasis of the other. According to Moertel, multiple primary cancers diagnosed within 6 months are considered concurrent, while those diagnosed more than 6 months apart are classified as late [16].

The World Health Organization (WHO) first recognized IMTs as a distinct entity in 1994 [17]. The 2020 WHO definition further describes IMTs as rare, rarely metastatic neoplasms composed of spindle myofibroblastic and fibroblastic cells, accompanied by an inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils [18]. The College of American Pathologists (CAP) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) recommend using the Pathologic Soft Tissue Stage Classification (pTNM; AJCC 8th Edition) to classify IMTs. This classification assesses the primary tumor (T), regional lymph node (N), and distant metastasis (M) categories based on the anatomical location of lesions, including the head and neck, trunk and extremities, abdomen and thoracic visceral organs, retroperitoneum, and orbit [10, 18].

The etiology and pathogenesis of IMTs remain unclear, with contributing factors including inflammation, trauma, autoimmune diseases, previous surgery, viral infections, and abnormal myofibroblast proliferation. Tumorigenesis in most IMTs is associated with the translocation of the receptor tyrosine kinase gene, where a fragment of one chromosome relocates to another, forming an oncogenic fusion gene. Additionally, inversion, which involves the relocation of two different gene fragments within a single chromosome, can also occur. ALK gene translocation is detected in 50–60% of IMTs [10].

Most multiple primary cancers are diagnosed as late multiple primary cancers, with simultaneous multiple primary cancers being rare. The coexistence of multiple primary cancers and an IMT is an extremely rare pathological entity [19].

Abdominal localization and symptoms

IMTs can invade almost any anatomical region, with approximately 75% of cases localized in the abdominal cavity [10]. Within the female reproductive system, IMTs commonly affect the uterus, cervix, ovaries, fallopian tubes, broad ligament, pelvic cavity, and placenta, with the uterus and cervix being the most frequently involved sites [19–21]. Symptoms in these regions include flatulence, atypical abdominal discomfort, pelvic pain, menstrual disorders, and dyspareunia. However, many cases remain asymptomatic [22]. Serum cancer marker CA 125 levels may remain within normal limits unless the disease is diffuse and extensive [23]. Malignant behavior is often associated with factors such as tumor size greater than 10.5 cm, severe nuclear atypia, more than 18 mitoses per 10 high-power fields, and lymphatic infiltration [24].

In the pancreas, IMTs can develop in the head, body, or tail, sometimes causing such symptoms as large intestine obstruction, as reported in 1 case involving a tumor in the pancreatic tail [25–27]. The presence of IMTs in the ampulla of Vater is extremely rare [28]. Hepatic IMTs are also uncommon, accounting for less than 1% of liver tumors, often initially mistaken for hepatocellular carcinoma [29, 30]. Complications such as liver abscesses are rare [31]. Similarly, IMTs of the bile duct and spleen are exceptionally rare, with around 120 splenic cases documented in the literature, including instances in infants as young as 18 months [32–36].

In the gastrointestinal tract, IMTs typically occur in the small intestine and colon, where they develop in the submucosa, muscle tissue, or mesentery, causing symptoms such as abdominal pain, intestinal obstruction, or fever. Occasionally, they can lead to ileocolic intussusception or mimic a ruptured appendix, necessitating complete surgical resection [37–40]. Gastric IMTs, though rare, exhibit unique histopathologic changes, often located in the body and posterior wall of the stomach [41, 42]. Both the cervical and abdominal esophagus can be affected, making differential diagnosis from other submucosal tumors – e.g. lipomas, inflammatory fibromyomatous polyps, and leiomyomas – challenging [43–45]. Since 2015, fewer than 15 cases of esophageal IMTs have been reported [46]. IMTs of the rectum are also rare, with only 8 cases documented. In cases of recurrence or incomplete resection, chemoradiotherapy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are useful treatments [47, 48]. The first reported case of colonic IMT was by Coffin et al. in 1995, with approximately 60 cases documented since [49, 50].

IMTs of the peritoneum are similarly rare, occasionally involving the major fascia and mesentery. R1 or R2 resections in the mesentery often necessitate adjuvant therapies due to the complexity of achieving complete resection [51–54]. IMTs in the greater or lesser omentum can be mistaken for generalized peritoneal carcinomatosis, requiring histological confirmation for accurate diagnosis [55].

When affecting the kidney, IMTs can mimic renal cell carcinoma, requiring careful diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to preserve unaffected kidney tissue [56–58]. Few cases of adrenal gland IMTs have been reported [59, 60]. IMTs of the bladder and prostate are extremely rare, typically managed with limited surgical resections and minimally invasive techniques, depending on the tumor’s specific anatomy [61, 62]. Some cases have reported malignant transformation [63]. In the prostate, a high Ki-67 index (30%) may necessitate radical prostatectomy over transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) due to a high rate of local recurrence [64]. IMTs of the testis are rare and seldom recur, with very few cases affecting the vas deferens [65–67].

Head and neck, cardiovascular, and other locations

The localization of head and neck IMTs is uncommon, representing only 5% of all IMTs and 14–18% of extrapulmonary IMTs [68]. Infiltration of the thyroid gland by an IMT is extremely rare, with primary involvement of the thyroid gland being even rarer [69, 70]. IMTs of the larynx typically involve the vocal cords and present with symptoms such as changes in voice timbre (74%), wheezing (29%), and dyspnea (22%) [71, 72]. The main challenge with laryngeal IMTs is avoiding overtreatment with total laryngectomy; preoperative diagnosis with microlaryngoscopy and conservative operations utilizing laser technology are preferred [73].

IMTs rarely affect the musculoskeletal system, nerves, or vessels, with differential diagnosis often relying on imaging to distinguish them from schwannoma and leiomyoma [74, 75]. IMTs of the central nervous system are particularly rare, with only 49 cases reported in the English literature from 2003 to 2022 [76]. These tumors can be confused with meningiomas on imaging and with plasmacytomas immunohistochemically. Symptoms typically include headache, blurred vision, and diplopia, and some suggest that these tumors may originate from the dura [77]. Recent studies have indicated that IgG4 immunoglobulin may aid in diagnosing IMTs of the central nervous system [78].

Primary heart tumors are rare, with 70% being benign. Myxomas are the most common type, but IMTs of the heart are believed to be underdiagnosed [79]. The first report of a cardiac IMT was by Gonzalez-Crussi et al. in 1975 [80]. These tumors constitute less than 5% of primary heart tumors [81]. They can cause sudden death, even in young individuals, and commonly affect the right atrium, right ventricle, tricuspid valve, and ventricular septum [82, 83]. Primary involvement of the pericardium can lead to cardiac tamponade [84]. When IMTs originate from the ascending aorta, they can be mistaken for tumors of the anterior mediastinum, such as invasive thymomas, and often require extracorporeal circulation for effective surgical treatment [85].

IMTs of the breast are rare, with no reported cases of axillary involvement, making sentinel lymph node screening unnecessary [86]. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the breast in males can mimic malignancy [87].

Pulmonary localization

A pulmonary IMT was first described by Harold Brunn in San Francisco in 1939 [88]. The term “inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor” was later established by Pettinato et al. in 1990 [89]. To date, approximately 500 cases have been reported in the literature, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 0.04% to 0.7%.

The incidence of IMTs among all lung neoplasms is estimated to be between 0.04% and 1% [90, 91]. Pulmonary IMTs are more commonly observed in children and adolescents. These tumors are primarily located in the parenchyma and are rarely endobronchial. Only 136 cases have been reported in the English literature, representing 5% to 12% of all cases [92–94]. They rarely present as an intrabronchial rupture of a hydatid cyst [95].

IMTs of the pleura are exceedingly rare [96], and those occurring in the trachea are often initially misdiagnosed as bronchial asthma [97]. The occurrence of IMTs on the chest wall is also very rare [98]. According to a study by Irodi et al., 36% of IMTs develop in the lung parenchyma, 23% in the lung parenchyma with extension to the mediastinum and pleura, 27% are intrabronchial, and 14% of cases are multifocal. The main symptoms observed were fever, hemoptysis, and cough, with calcification of the lesion seen in 32% of cases [99].

Lung transplant patients have a higher risk of developing malignancies compared to the general population, with approximately 16% to 32% developing cancer within 5 to 10 years after transplantation [100, 101]. However, the occurrence of IMTs in transplanted lungs is extremely rare [102]. In some rare cases, pulmonary IMTs may present with metastases at the time of diagnosis, which are also treated with corticosteroids [103]. In the study by Demir and Onal, dyspnea and cough were the predominant symptoms, while 25% of patients were asymptomatic [104].

Differential diagnosis and diagnostic procedures

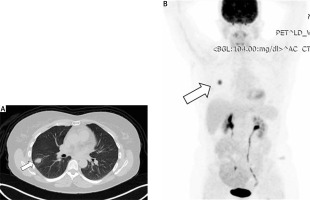

On conventional chest X-ray, an IMT of the lung appears as non-specific shadowing. However, computed tomography (CT) (Figure 2 A) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast provides more detailed imaging. These scans reveal the mass as either circumscribed or infiltrative, heterogeneous or homogeneous, and characterized by varying degrees of vascularity, with or without calcifications. These tumors are typically located in the lower lobe and peripheral parenchyma. They may also show necrosis, cavitation, air bronchograms, and increased 18F-FDG uptake with elevated SUVmax, usually without metastases (Figure 2 B). Combining imaging modalities, such as CT, 18F-FDG PET/CT, and bone SPECT, can aid in accurate diagnosis, determination of tumor extent, and treatment planning [105].

Figure 2

A – Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest reveals a neoplastic mass in the right lower lobe of the lung. B – Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan of the lung neoplasm showing a maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 8.2, indicative of high metabolic activity

The differential diagnosis for IMTs includes several other conditions: inflammatory fibrous polyps, inflammatory well-differentiated liposarcomas, epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma (EIMS), which has an aggressive clinical course and poor prognosis, stromal tumors such as gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), mesenchymal tumors, which are rare before age 40, and desmoid fibromatosis, mainly found in the mesentery. Idiopathic systemic diseases related to IgG4 must also be considered, particularly when the IgG4/IgG ratio exceeds 40% and serum IgG4 levels are elevated [10, 106]. An overview of the differential diagnosis is presented in Table I. Clinically, distinguishing IMTs from lung cancer, carcinoid tumors, and specific lung infections such as actinomycosis, aspergillosis, cryptococcosis, and hamartomas can be challenging [107, 108]. Accurate diagnosis requires comprehensive histopathological and genetic examinations.

Table I

Overview of the differential diagnosis of IMTs, highlighting key characteristics

Histopathological characteristics

Advanced imaging techniques, including diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) measurements, PET/CT, and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or fine-needle biopsy (FNB) of the nodule, are essential for definitive diagnosis and treatment planning of IMTs [109, 110]. However, sometimes the tissue obtained from puncture biopsies is insufficient, delaying the confirmation of diagnosis until surgical treatment is performed [111]. Interdisciplinary collaboration is crucial to establish a clear preoperative diagnosis, which aids in selecting the optimal surgical intervention, aiming for the best therapeutic outcomes and rapid patient recovery [112].

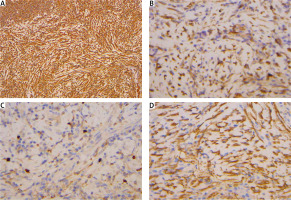

IMTs are immunohistochemically positive for mesenchymal markers such as vimentin (99%), smooth muscle actin (92%), and desmin (69%), but negative for cytokeratin, CD34, S-100, and epithelial membrane antigen (Figure 3) [113]. Studies indicate that positive ALK-1 staining, observed in 60-89% of cases, correlates with a favorable prognosis [114, 115]. A high Ki-67 index, greater than 20, is a risk factor for tumor progression, although it is not necessarily indicative of recurrence [116].

Figure 3

Immunohistochemical analysis. A – Vimentin positive staining at 100× magnification. B – Calponin positive staining at 400× magnification. C – Smooth muscle actin (SMA) positive staining at 400× magnification. D – Ki-67 staining at 400× magnification, demonstrating a proliferation index of 1–5% in neoplastic cells

Intraoperative rapid biopsy is critical for finalizing the diagnosis, as it helps guide the optimal resection operation, ensuring complete removal of the disease while minimizing the excision of functional lung parenchyma and avoiding extensive lymph node dissection. However, intraoperative diagnosis was achieved in only 14.2% of cases in the study by Peretti et al., and in 20% of cases in the study by Yüksel et al. [117, 118].

Emerging techniques, such as next-generation sequencing (NGS) and computer-aided histopathological diagnosis, may provide deeper insights into the biology of IMTs and assist in selecting the most appropriate treatment strategies [119].

Surgical treatment

The optimal treatment for IMTs is radical surgical excision with clear margins, known as R0 resection [10]. This approach aims to remove the tumor entirely, including any potential microscopic disease, to minimize the risk of recurrence. Complete excision of the neoplasia, including procedures such as segmentectomy, lobectomy, and lymph node dissection, is ideally performed using uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). VATS offers the advantages of being minimally invasive, leading to shorter recovery times, less postoperative pain, and reduced complications compared to traditional open surgery [119].

Achieving complete (R0) resection of IMTs can be challenging due to the tumor’s potential size, location, and involvement with surrounding structures. The anatomical complexity of the tumor’s position can complicate surgical planning and execution. Despite these challenges, complete resection rates range from 72% to 89% [120–123]. These rates underline the importance of meticulous surgical technique and thorough preoperative planning to maximize the likelihood of achieving clear margins.

In cases where complete resection is not feasible due to the tumor’s size or location, partial resection followed by close monitoring and additional treatments such as targeted therapy or radiotherapy may be considered. A multidisciplinary team approach, involving thoracic surgeons, oncologists, and radiologists, is crucial to develop a comprehensive treatment plan tailored to the individual patient’s needs [122–124].

For endobronchial IMTs, a multimodal therapeutic bronchoscopic management approach has been proposed, offering durable local control. This method should be considered as a frontline treatment for proximal lesions with a limited base (< 10 mm²) due to the low likelihood of metastatic spread and delayed local recurrence [125].

Recurrence rates

As previously mentioned, complete surgical resection (R0) is crucial, as positive surgical margins significantly increase the risk of tumor recurrence and mortality [126]. The recurrence rate of IMTs can be as high as 60%, but complete resection significantly reduces this probability to around 2% [127]. Despite the low recurrence rate following complete resection, long-term follow-up is strongly recommended, as recurrences have been reported even after 11 years [128].

IMTs of the lungs rarely infiltrate the airways. Most of these tumors develop in the periphery of the lungs, primarily in the lower lobes. Intrabronchial localization of pulmonary IMTs is exceedingly rare, occurring in less than 1% of cases. When an IMT develops with intrabronchial extension, invasive bronchoscopy combined with complete surgical resection ensures effective treatment while avoiding major resectional operations, such as pneumonectomy [129, 130].

Given the potential for high recurrence rates, even after what appears to be a complete resection, diligent long-term follow-up is essential. This includes regular postoperative imaging and clinical assessments to detect any signs of recurrence early, allowing for prompt intervention. Advances in surgical techniques and perioperative care continue to improve outcomes for patients with IMTs, making surgery a cornerstone in the management of this rare but challenging condition. Effective management of IMTs relies on a multidisciplinary approach involving thoracic surgeons, oncologists, and radiologists to ensure comprehensive care. Continuous monitoring and advancements in treatment strategies are crucial to reduce recurrence rates and enhance patient prognosis [126, 130].

Chemotherapy and targeted therapy

Chemotherapy as an adjuvant treatment for IMTs is generally not recommended but may be necessary when complete surgical resection is not feasible [10]. Anticancer pharmacotherapy is divided into classical and targeted therapies. Classical chemotherapy utilizes conventional drugs, with vinblastine and methotrexate being among the most effective regimens [131].

Targeted therapy, however, involves the use of antibodies directed against specific antigens involved in tumorigenesis, such as anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), protein tyrosine kinase ROS1, and neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase types 1 and 3 (NTRK1/3). These fusion genes produce proteins that can be targeted using tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). First-generation agents (e.g. crizotinib), second-generation agents (e.g. alectinib, ensartinib, ceritinib, and brigatinib), and third-generation agents (e.g. lorlatinib) have shown efficacy in treating IMTs with these genetic alterations [131–133]. ALK expression is found in approximately 50% of IMTs, making crizotinib a particularly effective treatment choice for these cases [134].

Liver metastasis from pulmonary IMTs is rare [135]. However, treatment of bilateral pulmonary IMTs with naproxen (250 mg twice daily for 1 month followed by 250 mg once daily for 1 month) has shown significant radiographic remission on CT scans [136]. For patients with inoperable IMTs, combinations such as pemetrexed (500 mg/m²) with carboplatin or pemetrexed (500 mg/m²) with cisplatin (60 mg/m²) have provided symptom relief and disease control [137]. It is however important to note that while naproxen, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), has shown some efficacy in treating specific cases of IMT metastases, particularly in reducing tumor size and symptom relief, it is not considered a replacement for traditional chemotherapeutic agents such as carboplatin or pemetrexed. Naproxen’s mechanism is believed to be related to its anti-inflammatory effects, which may contribute to tumor regression in select cases. However, chemotherapy remains the standard of care for more aggressive or inoperable tumors, as it targets the malignancy more directly. The use of NSAIDs such as naproxen is typically reserved for cases where conventional treatments are not viable, or as an adjunct to other therapies.

Various cytotoxic agents or regimens have been reported in the treatment of pulmonary IMTs, including methotrexate, vinorelbine, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, carboplatin, paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and etoposide [138]. While chemotherapy remains a secondary option, its role is crucial in managing cases where surgical intervention is not viable.

Immunotherapy

Innovative treatment approaches are being explored for managing IMTs. Notably, PD-L1 expression has been identified in 80% of recurrent or metastatic IMTs and in 88% of ALK-negative IMTs. This high prevalence of PD-L1 suggests that therapies targeting immune checkpoints may offer a promising alternative for IMT treatment [18, 139, 140].

Emerging research highlights the potential of high tumor mutational burden as a biomarker for predicting the success of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in cancer treatment. For IMTs, data from the CREATE trial revealed an average of seven mutations per megabase, indicating an intermediate level of mutational burden. Interestingly, no link was found between the loss of 12q24.33 and the mutational burden, suggesting that the POLE deletion does not influence the mutational landscape in these tumors. Currently, prospective studies specifically evaluating the efficacy of ICIs in IMTs are lacking [18, 141]. Several recent case reports have demonstrated the potential effectiveness of ICIs in treating sarcomas, including IMTs [142, 143].

Steroid treatment

Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of oral steroids in treating patients with IMTs. For example, the administration of cortisone in patients with pulmonary IMTs has shown significant positive responses. Follow-up using FDG PET/CT 3 weeks after the initiation of cortisone treatment revealed a marked decrease in SUVmax from 15.1 to 5.4, indicating a substantial reduction in the tumor’s metabolic activity [144, 145].

However, it is important to note that some studies suggest that steroids may promote the recurrence of IMTs. This potential for increased recurrence necessitates careful consideration and monitoring when incorporating steroids into the treatment regimen [146].

Radiotherapy

While surgical resection remains the primary treatment for IMTs of the lung, radiotherapy has shown promise as an alternative or adjunctive treatment in certain cases. Low-dose radiotherapy, administered at 4 Gy-2 Gy per fraction, can achieve excellent responses in reducing tumor size and controlling disease progression. This approach is particularly beneficial for patients who are not ideal candidates for surgery due to the tumor’s location, size, or patient comorbidities [147].

In cases where complete R0 resection is achieved, patients with tumor sizes less than 3 cm in the greatest diameter have demonstrated excellent survival rates. Radiotherapy can play a crucial role in managing residual disease post-surgically or in situations where achieving clear surgical margins is challenging. Additionally, radiotherapy may be used palliatively to manage symptoms and improve the quality of life in patients with advanced or inoperable IMTs [148, 149].

Expanding the role of radiotherapy in IMT treatment protocols requires further research and clinical trials to establish optimal dosing schedules, long-term efficacy, and potential side effects. The integration of advanced radiotherapy techniques, such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) and stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), may enhance the precision and effectiveness of treatment, minimizing damage to surrounding healthy tissues [149]. Overall, while surgery remains the cornerstone of IMT treatment, radiotherapy offers a valuable adjunctive option, especially in complex cases where complete surgical resection is not feasible or in recurrent disease scenarios.

Future perspectives

Looking ahead, the management of IMTs presents several challenges and opportunities. The treatment landscape for IMTs is evolving, but several concerns remain. The current reliance on off-label use of crizotinib for ALK-rearranged IMTs underscores the urgent need for regulatory-approved therapies. Despite its effectiveness, crizotinib’s high cost and limited availability, especially in developing regions, restrict its use. Furthermore, resistance to crizotinib, such as the emergence of ALK (G1269A) mutations, poses a significant hurdle, necessitating the development of second-line treatments such as ceritinib. To improve patient outcomes, a deeper understanding of resistance mechanisms and the development of affordable and accessible treatments are essential [18].

Future research should focus on the optimal timing and application of ALK inhibitors. Exploring the benefits of adjuvant therapy following complete surgical resection could be particularly beneficial for aggressive cases such as epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma (EIMS). The potential for neoadjuvant therapy with ALK inhibitors also offers promising avenues, as it allows for the evaluation of tumor responses to systemic treatment before surgery [150]. This strategy not only aids in better surgical planning but could also inform prognostic assessments and tailored adjuvant treatments. Continued advancements in this area, supported by robust clinical trials and international collaboration, are critical for developing more effective and comprehensive treatment protocols for IMT patients.

Results

This review highlights key findings on IMTs, emphasizing their rarity and clinical variability across different anatomical locations. IMTs most commonly affect children and young adults, with pulmonary IMTs being the most prevalent subtype. Symptoms vary by location, ranging from respiratory issues (cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea) in pulmonary cases to obstructive symptoms in abdominal or gastrointestinal IMTs. Systemic inflammatory markers, such as elevated C-re- active protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, were consistently observed. Diagnostic imaging (CT, MRI) played a central role in identifying these masses, and histopathology often revealed spindle cell proliferation and inflammatory infiltrates. Approximately 50% of cases showed ALK gene translocation, influencing treatment approaches.

Surgical resection (R0) remains the primary treatment, with significantly reduced recurrence rates (2%) when complete resection is achieved. In cases where complete resection was not feasible, partial surgery combined with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or emerging targeted therapies (e.g., ALK inhibitors such as crizotinib) offered potential benefits. Long-term follow-up is crucial, given the risk of late recurrence. Steroid and radiotherapy treatments also showed effectiveness in specific scenarios, though their application requires careful monitoring.

Overall, this review underlines the importance of early diagnosis, individualized treatment plans, and multidisciplinary care. Emerging therapies, including targeted treatments and immunotherapy, provide promising alternatives, particularly for ALK-positive or inoperable IMTs.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the rarity of IMTs results in a limited number of available case reports and studies, which constrains the comprehensiveness of the data analyzed. Secondly, the heterogeneity of the included studies, in terms of diagnostic methods, treatment protocols, and follow-up periods, complicates direct comparisons and the formulation of standardized treatment guidelines. Additionally, the retrospective nature of many studies introduces potential biases and limits the ability to establish causal relationships. Finally, the absence of prospective clinical trials on emerging therapies such as ALK inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors restricts our understanding of their efficacy and optimal use in IMTs. Future research should aim to address these gaps through multicenter collaboration and well-designed clinical trials.

Conclusions

IMTs are rare neoplasms with complex clinical presentations and challenging treatment paradigms. While surgical resection remains the cornerstone of therapy, achieving complete (R0) resection is often difficult due to the tumor’s potential size, location, and involvement with surrounding structures. The high recurrence rates necessitate diligent long-term follow-up. Advances in imaging and surgical techniques have improved diagnostic accuracy and treatment outcomes, but there remains a significant need for effective adjuvant therapies. Emerging treatments, including targeted therapies such as ALK inhibitors and immunotherapy, show promise but require further investigation. As our understanding of the molecular and genetic underpinnings of IMTs evolves, new therapeutic avenues may become available, offering hope for better management of this challenging condition. Continued research and collaboration across specialties are essential to optimize treatment strategies and improve patient outcomes in IMTs.