Summary

Observations from our previous studies and other reports suggest the need to introduce higher intensity post-operative rehabilitation in patients who undergo cardiovascular surgery. The study analyzed the standard as well as the modified rehabilitative models. It is evident that the modified program has a more positive impact on patients’ physical fitness, allows for a faster physical recovery, and is safe for patients. The results should contribute to counteracting the effects of immobilization of patients resulting from cardiovascular surgery.

Introduction

New positions on the secondary prevention of atherosclerosis risk factors are continually being developed worldwide [1]. Recently, major cardiology organizations such as the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (EACPR), the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR), and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) have issued their recommendations. All of them emphasize that an appropriately selected rehabilitation model should result in an increase in physical capacity and in improved exercise tolerance [2, 3].

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) has evolved over several decades from simply monitoring the process of safe return toward basic physical functioning, to a multidisciplinary approach that encompasses patient education, lifestyle modification, psychosocial rehabilitation, clinical assessment, diagnosis, monitoring of CR progress, and conducting an appropriately tailored program of recovery through physical training. This multidisciplinary approach is now referred to as comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation (CRC) [4–6].

In recent years, CR has primarily developed due to the outcomes of scientific research [3]. The American Heart Association’s 2007 scientific statement on medically supervised exercise training in cardiac patients shows that the risk of serious cardiovascular events due to physical strain occurs in only 1 case per 60 000 to 80 000 patient-hours. Such data endorse the safety of properly selected and conducted exercise [7].

Aim

The main purpose of this study was to compare, in terms of therapeutic effectiveness, two models of physical recovery in the early postoperative period in patients after surgical myocardial revascularization in the treatment of coronary artery disease. Additional objectives: to evaluate the effects resulting from increased exercise intensity and to assess the training models used in terms of safety.

Material and methods

The study was conducted from January 2015 to September 2018 in the Department of Cardiac Surgery of the 1st Department of Cardiology of the Medical University of Warsaw (now called the Department of Cardiac, Thoracic and Transplant Surgery). The study included 100 men with stable coronary artery disease who underwent elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

After meeting the eligibility criteria – male gender, diagnosis of stable coronary artery disease, CCS scale ≤ II, NYHA scale ≤ II, left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ 40%, more than 4 weeks since myocardial infarction if present, no prior cardiac surgery, no gait dysfunction, no chronic kidney disease, absence of permanent cardiac pacing, distance of over 300 m in the preoperative 6-minute walk test, elective admission for surgery, logical contact with the participant – the patients were randomly assigned (using sealed envelopes) to two 50-person groups. The standard model involved rehabilitation according to the recommendations of the PTK Section of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology (gold standard), according to Rudnicki, 2004, which were in effect during the studied period [8]. The intense model involved rehabilitation according to the author’s model, which was characterized mainly by a higher intensity compared to the standard model. Program differences between the two groups included: dosage of training loads, length of exercise time, type and progression of exercises, and range of functionality (Table I).

Table I

Program differences between groups

The 6 minute walk test (6MWT) was used to verify the effects of the rehabilitation programs used, and was performed twice [9]. The first trial was conducted before surgery to ascertain eligibility and determine the initial physio-functional status. The second trial took place on postoperative day 6 and aimed to re-evaluate the physio-functional state for study group comparison.

Statistical analysis

Non-parametric tests were chosen to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics such as median, quartiles, and minimum and maximum values were used in the study. Also, the mean and standard deviation were used when it was considered relevant for interpretation. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test was used to show the differences between the numerical values of the studied variables between groups. When analyzing differences in related traits – the time interval between two measurements – in each group, the Wilcoxon paired rank-order test was used. Analysis of quantitative traits was performed using the χ2 test or, where case counts were small, Fisher’s exact test. The level of statistical significance was defined as α = 0.05, and results were considered significant when p < α. Test calculations and analyses were performed using the MedCalc package (v18 licensed from the Department of Medical Informatics and Telemedicine at the Medical University of Warsaw).

Results

Comparison of population characteristics and the initial and postoperative parameters between the standard model and intense model showed differences only in LVEF and smoking (Tables II and III). The studied data included: age, body mass index (BMI), EuroSCORE II, LVEF, motor dysfunction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), CCS scale, NYHA scale, history of myocardial infarction, duration of surgery, duration of ventilator therapy, perioperative vasopressors, transfusion of packed red blood cell concentrate transfusion (pRBC), fat-free plasma transfusion (FFP), and platelet concentrate transfusion (PC).

Table II

Baseline parameters for group standard model and intense model

[i] SI – statistically insignificant; p > 0.005, EF – ejection fraction, COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CKD – chronic kidney disease, STEMI > 4 w – ST elevation myocardial infarction within the prior 4-week period, NSTEMI > 4 w – non-ST elevation myocardial infarction within the prior 4-week period.

Table III

General postoperative summary for standard model and intense model

[i] Respiratory therapy – total hours, HR POD 1 – heart rate post-operative day 1, pRBC – packed red blood cell concentrate transfusion, FFP – fat-free plasma transfusion, PC – platelet concentrate transfusion, Trop. T POD 1/2 – troponin T postoperative day 1/2, CK-MB POD1/2 – creatine kinase muscle-brain postoperative day 1/2, IABP – intra-aortic balloon pump.

Comparing the standard model and intense model with each other using the 6MWT showed statistically significant differences, with p < 0.05.

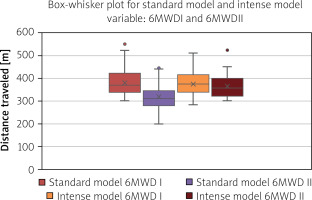

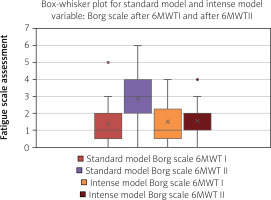

In the initial 6MWT, designed to verify and determine preliminary values, subjects in the standard model achieved a higher SpO2 (median: SM = 97%, 98%; IM = 96%, 97%). The other results were not significantly different. In the final 6MWT, which was designed to evaluate the effects of the rehabilitation programs used, subjects in the intense model obtained a higher SpO2 (median: SM = 96%, 97%; IM = 97%, 98%), lower initial HR (median: SM = 84; IM = 78) and lower post-exercise HR (median: SM = 92.5; IM = 84.5), longer distance travelled (median: SM = 312m; IM = 359m) (Figure 1), lower fatigue level according to Borg (median: SM = 3; IM = 1) (Figure 2), and shorter postoperative ICU stay. The other results were not significantly different.

Comparing the results within a group showed statistically significant differences with p < 0.05. In the standard model: SBP and SpO2 in the initial test were higher than in the final 6MWT, HR in the initial test was lower than in the final 6MWT, distance travelled in the initial test was longer than in the final 6MWT, and the Borg fatigue level in the initial test was lower than in the final 6MWT. The other results were not significantly different. In the intense model: SBP in the initial test was higher than in the final test of the 6MWT; SpO2 and HR in the initial test were lower than in the final test of the 6MWT. The other results were not significantly different.

Comparing the standard model and intense model in terms of minimum due values for 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) showed no statistically significant differences. Comparing the calculated minimum due values with the results of 6MWD I and 6MWD II per group showed a statistically significant difference with p < 0.05 only in the standard model for 6MWD II. The median for 6MWD II was 312 m (mean ± SD: 320.76 ±56.78) (95% CI: 305–336), and for the minimum due value was 351.84 m (mean ± SD: 367.93 ±57.84) (95% CI: 352–384), which showed a statistically significant difference, with p < 0.0001.

Discussion

We analyzed two rehabilitation models for physical recovery after coronary artery bypass graft surgery in the early postoperative period. The existing standard and the intense modification were both analyzed individually and compared to each other. Long-term observations of our own indicated the need for intensification of hospital rehabilitation programs [10]. In this study, the following questions were posed: Will the planned modifications positively improve physical fitness in relation to the standards, and will they be safe for patients?

The distance achieved during the walking test was the most important factor in the 6MWT test, and the final interpretation was made based on it. Evaluating the results obtained in terms of distance travelled during the 6-minute walk showed that the differences between the two groups were statistically significant. Two marching trials were performed during the studied period. The first trial (qualification) took place before surgery at the beginning of the studied period, while the second trial (verification) was performed on postoperative day 6 as the final procedure for the studied period. In the first trial, the difference between the median 6MWD in the two groups was not significant and was only 6 m. Such a result argues for baseline uniformity between the studied groups. In contrast, the second trial showed a significant difference between groups, in which the longer 6MWD was achieved by the subjects in the intense model, with a median difference of 47 m.

Interestingly, the marching trials result analysis shows a significant difference between the initial and the final march in the 6MWT test only in the standard model. Respondents in this group achieved a median 6MWD in the final test 58 m shorter than the initial test, indicating a decrease in marching ability among these subjects. The intense model achieved a similar 6MWD result in the initial and the final marching test, which is important for the study as a whole. It is not expected to observe a repetition or even improvement in the distance achieved within the few postoperative days, as reported in the literature. Hirschhorn et al. compared the effectiveness of two rehabilitation programs in the early period after CABG. Their results showed a significant decrease in the walking distance achieved at discharge, compared to pre-surgery [11].

An interesting observation for both groups is the lack of a statistically significant correlation of the 6MWD with BMI and an average negative, although significant, association with age. There is a dispute in the scientific field regarding the possible influence of BMI and age on the 6MWD score. There are authors who argue that gender, BMI, and age have a significant relationship with the 6MWD distance obtained. They include Enright et al., who stated that the patient’s age, weight, and height determine the 6MWD. Therefore, these authors suggest using the equation of due values to establish reference values [12]. In opposition to the theory of the relationship between the 6MWD and age and BMI are, among others, Przysada et al. The results of their study on the evaluation of exercise tolerance in patients rehabilitated after CABG show that the age of the subjects and BMI had no effect on the distance achieved [13].

A common correlation of 6MWD for both groups, which was statistically significant, also occurred in the association with EuroSCORE II and 6MWD difference, and between 6MWD I and 6MWD II. In the case of EuroSCORE II, the relationship with 6MWD was found to be negative on average in both groups. In contrast, the relationship between 6MWD and 6MWD-difference was highly positive for the standard model and on average positive for the intense model. For the relationship between 6MWD I and 6MWD II, the relationship was highly positive in both groups. The correlogram for the 6MWD also showed individual statistically significant relationships that occurred within the groups. In the standard model, these were weakly negative relationships of II HR before, and average relationships of II HR after. In the intense model, these were average negative correlations with those on the day of discharge and the Borg I scale, and an average positive correlation with I SpO2 after. Attention should be drawn to the mentioned correlation of 6MWD I and 6MWD II with the day of discharge, which occurred only in the intense model, because in the case of the day of discharge we also have a statistically significant difference regarding the length of hospitalization between the two groups. In the intense model, patients were discharged from the hospital faster, with an interquartile range (Q1–Q3) of 6–7 days.

In the present study, despite the lack of strict guidelines, it was also decided to analyze the percentage of due value for 6MWD. In order to make the results consistent, the equation according to Enright and Sherrill with the calculation of the minimum value was used [14].

Looking at the results of the minimum due values in the two groups, several similarities were observed. When comparing them with the initial 6MWD, there was no statistically significant difference, and the median difference was: in the standard model, the due value was 18 m lower; in the intense model that difference was smaller at 2 m in favor of the 6MWD. A comparison with the 6MWD from the final test showed a statistically significant difference in the standard model, where the subjects achieved a median of 40 m lower than the reference values. In the intense model, no statistically significant difference was found, with the subjects achieving a median of 15 m below the reference value. On the other hand, comparing the calculated due values for the two groups, there were no statistically significant differences evident. Taking the above results into account, it was noted that there was an analogy between the results obtained in the 6MWD and the due values for the study groups. When analyzing the initial 6MWD and corresponding reference values in both of these results, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups, as well as within the groups. However, when considering the final 6MWD and the corresponding reference values in both of these results, statistically significant differences were found only for the subjects in the standard model, who achieved a significantly shorter distance in the final 6MWD compared to the initial 6MWD, and the distance of the final 6MWD was significantly shorter than the affiliated reference values. In conclusion, we see that common conclusions were reached for the 6MWD marching trial and for the corresponding reference values.

Considering the achieved values of 6MWD, it was evident that a seven-day procedure (starting on postoperative day zero) conducted according to the modified intense model and including subjects in the intense model, was more effective than the standard procedure including subjects in the standard model. The superiority of intense training combined with psychoeducation, over lower-intensity training, in early hospital rehabilitation after myocardial revascularization is described in a study by Hojskov et al. In this pilot study, the authors observed that the group of patients who received more intense rehabilitation achieved a longer 6MWD in the final walk test by an average of 93 m compared to the group of patients who were rehabilitated less intensively [15].

The present study assessed physical fitness using additional components.

BP measurement was one of the items used to interpret the 6MWT. There was a statistically significant relationship between initial and final SBP in 6MWT trials in both groups. The week-long rehabilitation resulted in: in the standard model, a decrease in median SBP of 5 mm Hg; and in the intense model, a decrease of 7.5 mm Hg. Similar results regarding the effects of short-term physical activity on BP reduction were obtained in the study by Kokkinos et al., where the BP reduction effect was obtained after just 3 weeks of moderate to vigorous physical activity. They noted a SBP/DBP reduction of average 8/4 mm Hg in women and 9/5 mm Hg in men [16].

Comparing the two study groups in terms of HR showed statistically significant differences both before and after the marching test, but only in the final 6MWT. The subjects in the intense model obtained lower HR values. The median HR difference between the groups was 6/min before the marching test and 8/min after the marching test. According to Amorim et al., the greatest reduction in HR, which indicates cardiovascular functional improvement, occurs in the first 4 weeks after commencement of exercise. Their trial was performed on 250 post-ACS patients who were consecutively referred for CR [17].

The next element used in the interpretation of the 6MWT was the SpO2 measurement. SpO2 in the standard model at the final test decreased significantly with respect to the initial test. In the intense model, the opposite effect was observed: a statistically significant increase in SpO2 at the final test relative to the initial test. In a study conducted by Nardi et al. on early hospital rehabilitation after cardiac surgery, a similar end result was obtained. Their study examined three groups of patients, divided by exercise intensity. After only a few days of rehabilitation, subjects in the groups with a more intense improvement achieved higher SpO2 values during the final 6MWT [18].

The subjective Borg scale was the final additional component of the 6MWT used to assess physical fitness. The scale was used twice in the study, in the initial test and in the final 6MWT. The initial test showed no statistically significant difference between the groups of subjects. In the final test, the difference was statistically significant. Intense model subjects expressed a 2-point lower fatigue level than standard model subjects.

The present study did not include an analysis of the continuous HR and SpO2 measured during the marching trials, nor their peak values. There are no clear guidelines as to the need for such analysis. Moreover, it was found that the measurements taken may not be valid due to potential artifacts induced by the physical activity.

Patients were not subdivided based on established factors that can affect the 6MWT distance obtained, which include gender, BMI and age (male gender was one of the eligibility criteria). It should be noted that all three of these components were the basis for calculating the due values, which were used in interpreting the results. In the case of BMI, there was no evident correlation with the distance achieved. In the case of age, a correlation did occur, but it applied to both groups to the same degree. As mentioned above, there are studies that, similarly to the present study, exclude correlations between the above variables. It is noteworthy that the two groups did not statistically differ in terms of BMI, age, or gender.

Based on the analysis of the results obtained with the 6MWT, it was found that the therapeutic effect was different in the two groups. Patients in the intense model underwent more intense training, achieved greater physical capacity and general fitness, and their inpatient treatment was completed quicker. The proposed program was safe and well tolerated. It should be noted that the rehabilitation program according to the SRKiFW PTK, which covered the subjects in the standard model, has been since updated, and a revised version is now in effect. According to the latest guidelines, more intense intervention has been introduced into the program. However, when comparing the current recommendations with the modified intense model presented in the study, differences are apparent, mainly regarding the length of exercise sessions, exercise intensity, and dosage of functional range.

Applications

The authors’ intense intervention program, applied in the early hospital period to patients after coronary artery bypass grafting in the process of treating coronary artery disease, has a more beneficial effect on improving overall physical fitness than the standard program.

Patients rehabilitated according to the authors’ program achieved greater functional capacity faster than the patients rehabilitated according to the standard program.

Increasing the load, extending the duration of exercise sessions and expanding the range of functionality were safe for and well tolerated by patients.