Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) is a complication of pregnancy, comprising implantation of the zygote outside of the uterine cavity. Ectopic pregnancy is a leading cause of pregnancy-related maternal death in the first trimester. Implantation usually takes place in the ampullar or isthmic part of the fallopian tubes. In 2–4% of cases implantation develops in the interstitial part of the uterine tube and is called interstitial pregnancy (IP) [1–3]. This condition represents a major diagnostic and therapeutic problem and is associated with high rates of complications [4].

Diagnosis is often delayed due to non-specific symptoms and the possibility of the interstitial portion of the fallopian tube expanding more than the other tubal segments. Diagnosis at early gestational age is essential for reducing the rate of complications, and it is based on the clinical signs, transvaginal ultrasound examination, and serum β-chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) levels. Several treatment options are known, but surgery is still the main one, particularly using minimally invasive techniques.

We present a case report related to a multiparous woman who presented with amenorrhoea and specific ultrasonographic findings for interstitial pregnancy. The patient was treated laparoscopically. Due to the structure of the presented material in this case report, no approval by an Ethics Committee was required. Hence it was sufficient for the patient only to sign an informed consent form.

Case report

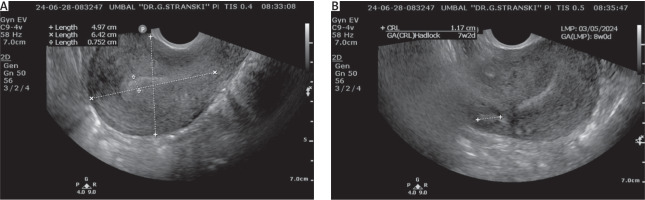

A 38-year-old multiparous woman presented with secondary amenorrhoea, positive pregnancy urinary test, and subjective symptoms of early pregnancy. Her obstetric history included 5 normal vaginal deliveries and 2 spontaneous abortions in early gestational age, and her past surgical history included appendectomy. The patient denied any other comorbidities or medication intake. Vaginal examination established a normal cervix, normal vaginal discharge, anteflexed uterine body that was normal in size and mobility, left adnexa was normal on palpation, there were no pelvic masses, and peritoneal signs were negative. Transvaginal ultrasound revealed an empty uterine cavity and an embryo within the gestational (GS) sac localised in the interstitial part of the right fallopian tube, with no signs of cardiac activity.

The crown-rump length (CRL) of the embryo was 11.7 mm corresponding to 7 + 2 gestational weeks (g.w.).

The diagnosis of IP was hypothesised when the patient presented with amenorrhoea, at an estimated gestational age of 8 g.w. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

A) Transvaginal ultrasound indicating empty uterine cavity, B) suspected right interstitial pregnancy

The serum level of β-HCG was 723.4 mIU/ml and typical ultrasound findings.

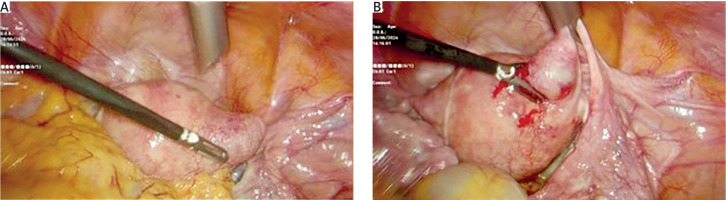

The case was discussed with the patient, and due to her haemodynamically stable state and reluctance for future pregnancy, the decision for laparoscopic treatment was made. During the surgical procedure, an intact IP localised in the interstitial portion of the right fallopian tube was confirmed (Fig. 2).

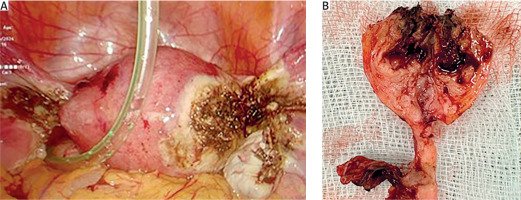

Bilateral salpingectomy was performed associated with resection of the interstitial portion of the right fallopian tube (Figs. 3 A, B).

Fig. 3

A) Postoperative view following the cornual resection and bilateral salpingectomy due to interstitial pregnancy, B) macro scopic image of the interstitial portion of the right uterine tube

The postoperative serum β-HCG level was 218 mIU/ml.

Postoperatively the patient was stable and therefore was discharged home.

Discussion

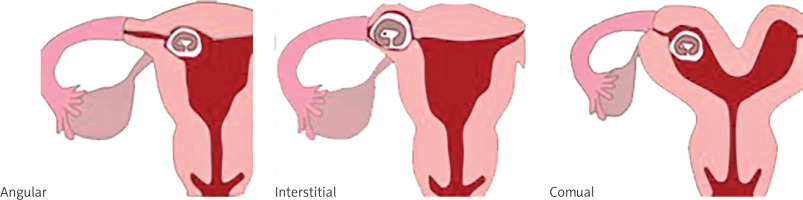

Interstitial pregnancy is defined as an EP developing in the intramural uterine part of the fallopian tube. Interstitial, cornual, and angular pregnancies are terms that are used interchangeably, so it is important to distinguish between them [1].

An angular pregnancy is a potentially viable intrauterine pregnancy with implantation in a lateral angle of the normal uterine cavity, medial to the uterotubal junction, which has the potential to behave as an EP [5]. Cornual pregnancy represents a pregnancy in a rudimentary horn or within one horn of a septate or unicornuate or bicornuate uterus (Fig. 4) [6, 7].

Interstitial pregnancy is one of the rarest kinds of EP, associated with higher rates of complications compared to usual ectopic pregnancies, so its early recognition is essential. Interstitial pregnancy accounts for 2–4% of tubal pregnancies, with increasing incidence due to extensive use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) nowadays [8]. Different risk factors for the development of tubal pregnancy include the following: tubal damage due to previous pelvic surgery or pelvic inflammatory disease, tubal and uterine abnormalities, previous EP, pregnancy conceived after in vitro fertilisation, and smoking. However, ipsilateral salpingectomy is the only known risk factor specific to IP [9].

Interstitial pregnancy can either be asymptomatic or present with the classic clinical triad of amenorrhoea, abdominal pain, and vaginal bleeding. The clinical manifestation depends on whether the pregnancy is intact or ruptured. Intact IP can be asymptomatic for weeks, due to the possibility of the interstitial portion of the fallopian tube being expanded more than other tubal segments before it ruptures. Ruptured IP leads to catastrophic intra-abdominal haemorrhage. This is due to its localisation in the upper lateral uterine segment, where there is extensive uterine-ovarian vessel anastomosis. This explains the higher mortality rate of IP and indicates the necessity of early diagnosis [10].

Although IP remains one of the most difficult gestations to diagnose, early diagnosis allows conservative treatment that can decrease the risk of future infertility and other complications.

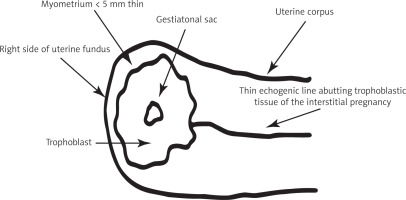

Pelvic ultrasonography is the main method of diagnosis. Typical sonographic findings in an IP include a gestational sac seen separated from the uterine cavity with a thin ring of myometrium surrounding the gestational sac [11]. Timor-Tritsch et al. [12] described the following transvaginal ultrasound criteria for the diagnosis of IP: (1) an empty uterine cavity; (2) a gestational sac located eccentrically and > 1 cm from the most lateral wall of the uterine cavity; and (3) a thin (< 5 mm) myometrial layer surrounding the gestational sac. “Interstitial line” sign is an additional sonographic feature expressed in linear echogenic endometrial lining extending to the edge of the eccentric GS. Ultrasound imaging of interstitial line is reported to be a highly sensitive and specific marker for the diagnosis of IP (Fig. 5) [13].

Fig. 5

Diagram describing the Timor-Tritsch transvaginal ultrasound criteria for diagnosis of interstitial pregnancy in early gestational age [12]

Magnetic resonance can also be used for the diagnosis of IP in non-urgent cases and in tertiary medical centres. The main advantage of magnetic resonance imaging as compared to transvaginal ultrasound is the ability to visualise the exact site of implantation and thus differentiate interstitial from cornual and angular pregnancy [14].

Clinical management of IP remains a debated topic. Various medical and surgical methods for the treatment of IP are known (Table 1). The treatment should be personalised, but the options depend on the gestational age at the time of diagnosis, whether the IP is ruptured or intact, and the patient’s desire for future fertility. Minimally invasive surgical techniques and nonsurgical treatment options can be used for non-ruptured IP. A ruptured IP requires immediate surgical treatment with either laparoscopy or laparotomy due to the high mortality rate [8].

Table 1

Treatment methods for interstitial pregnancy

| Non-surgical treatment | Surgical treatment |

|---|---|

| Systemic MTX (intravenously, intramuscular) [10] | Cornual resection [12] |

| Local MTX [10] | Cornuostomy [13–17] |

| Mifepristone + MTX [11] | Hysteroscopic aspiration [18] |

| Vacuum aspiration under laparoscopic guidance [18] | |

| Selective uterine artery embolisation [19–21] | |

| Hysterectomy |

Non-surgical treatment has been favoured to prevent scarring of the uterus, including systemic or local injection of methotrexate (MTX) [15–17] and a combination of MTX and mifepristone [18].

Success rates of pharmacological treatment with MTX depend on the general condition of the patient, gestational age, whether the pregnancy is intact or ruptured, the diameter of GS, and the basal level of β-hCG. There are reports of higher efficacy in haemodynamically stable women, with GS diameter less than 35 mm, β-hCG level below 5000 mIU/ml, and no foetal cardiac activity [19].

The presence of foetal cardiac activity, β-hCG level > 5000 mIU/ml, and ectopic mass size > 4 cm are relative contraindications for use of MTX in the treatment of IP.

Absolute contraindications are sensitivity to MTX, vitally unstable women, presence of heterotopic pregnancy with viable intrauterine pregnancy, elevated liver enzymes or high serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dl, low leucocytes and/or platelets less than 100,000 mm3, breastfeeding, active pulmonary disease, or peptic ulcer [15, 19]. This explains the necessity of strict evaluation of patients who are suitable for this method of treatment.

Stabile et al. reported successful management of IP with systemic multidose MTX associated with a single oral dose of mifepristone, and they underlined the efficacy of this combined therapy. Based on their results, a combined protocol, consisting of a systemic multidose MTX regimen with a single oral dose of mifepristone, is described as a first-line therapy in asymptomatic patients [20]. The main disadvantage of nonsurgical options is the risk of recurrence of tubal pregnancy due to the persistence of risk factors leading to development of IP.

Surgical treatment is based on classical surgical interventions, such as cornuostomy, cornual resection, or hysterectomy, and remains an important option because it offers definitive treatment. Alternative methods are also used nowadays. Wedge resection of the uterine horn increases the risk of uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancy, which makes this method inappropriate for patients with a desire for future fertility [8, 21].

Laparoscopic cornuostomy is a minimally invasive and effective method for the treatment of IP, which consists of removing the gestational sac with subsequent suturing of the cornual incision without removing the surrounding myometrium [22–25]. Lee et al. compared the clinical efficacy and safety of laparoscopic cornuostomy and cornual resection in the treatment of IP, exploring 75 patients, 53 of whom underwent cornual resection and 22 of whom underwent cornuostomy [26].

This research shows that laparoscopic cornuostomy reduces the time of operation. It lowers the incidence of uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancy, but it may have the same incidence of persistent IP as cornual resection.

Laparoscopic cornuostomy yielded clinical results comparable to those of cornual resection, therefore confirming the essence of cornuostomy, which is its suitability for women with future reproductive plans [26].

Transcervical vacuum aspiration and curettage under laparoscopic or hysteroscopic guidance is another possible method of treatment that provides an alternative conservative option for preventing future infertility in patients with future reproductive plans [27].

Selective uterine artery embolisation can also be used for selected patients with non-ruptured IP in early gestation. This therapeutic modality seems to be effective for conservative management of IP as a prophylactic measure before surgical intervention, to prevent major bleeding that increases the mortality rate [28–30].

Although it may adversely affect future fertility and pregnancies, surgery is the main option for the treatment of IP, especially at advanced gestational age and for high β-HCG levels, where systemic treatment with MTX is expected to be ineffective [31–34]. The dynamic development of endoscopic surgery in recent years has made the laparoscopic technique the treatment of choice in IP.

Conclusions

Interstitial pregnancy, as one of the rarest forms of EP, may cause life-threatening complications, so its early recognition is crucial. The incidence of IP is rising with the growing popularity of ART. Early ultrasound detection is of paramount importance to allow conservative treatment with MTX injections or conservative surgery such as laparoscopic cornuostomy, with the advantage of preserving future fertility.

Delayed diagnosis requires cornual uterine resection with all the complications for subsequent pregnancies that it implies. The poor prognosis of complicated IP is associated with a higher mortality rate, reported to be 15 times-fold higher than the mortality rate of other tubal pregnancies. Although it is a rare condition, clinicians should suspect this diagnosis in patients with known risk factors and specific ultrasound findings corresponding to the described criteria.