Introduction

Studies consolidate a healthy link between practicing physical exercise and the decrease and relief of some menopause symptoms [1–3]. There is evidence on physical exercise as a non-pharmacological treatment that can be aligned with pharmaceutical therapy, not only to reduce the intensity of the climacteric symptoms, namely somatic, psychological, and urogenital [4], but also as an important ally in reducing the natural limitations of the aging process and the onset of non-communicable diseases [5]. Some studies with menopausal women have already shown these beneficial effects, as seen in the randomised clinical trial by Berin et al. [6]. The trial involved a 15-week intervention using resistance training, which proved effective in reducing hot flashes, while promoting an increase in lean mass and strength. In addition, studies with aerobic training reported the effectiveness of aerobic training in improving cardiorespiratory fitness and reducing body fat in post-menopausal women [7]. The current clinical trial adopted an intervention including a combination of both aerobic and resistance exercise, known as concurrent training (CT), which is able to minimise the effects of aging on the metabolism as it results in improvement in the overall body composition, and the glycaemic and lipid profile of the general population [8–10].

However, to date, no studies were found that research CT and symptoms of depression, sexual function, and the perspective on aging/finitude perspectives in menopausal women concerning physical exercise, as studies tend to focus on the most common symptoms, such as vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats) and weight gain [6, 8, 11–13]. Despite this, an Umbrella Review that includes several types of physical exercise highlights the positive effects of these practi- ces, especially when related to depression [14]. Another systematic review supports the benefits of physical exercise for sexual function, although it suggests that new studies be carried out to strengthen the evidence [15].

Therefore, the current study represents a current and innovative approach that utilizes a CT protocol when compared to the control group. It brings new evidence to a highly relevant yet still underexplored subject, directly impacting the quality of life of symptomatic menopausal women [16]. Thus, the primary objective of this study is to analyse the effects of CT compared to the control group (CG) on menopausal symptoms, depressive symptoms, sexual function, and the aging perspective in menopausal women after a 4 month intervention. The hypothesis is that the exercise group will experience improvements in depression, sexual function, and aging perspective after 4 months of intervention.

Material and methods

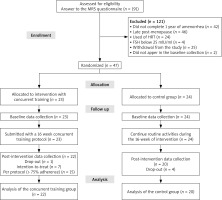

A randomised clinical trial with 2 arms was designed in accordance with the CONSORT 2010 guidelines (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). This study is a part of a 3-arm randomised controlled clinical trial with follow-up, which followed the same methodology (eligibility criteria) as a previously published study [17], but only 2 arms were analysed at 2 times. All procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of a University of Brazil (name of the University and number blinded for review), registered on the REBEC (Brazilian Registry of Clinical Trials) platform (number blinded).

Study participants

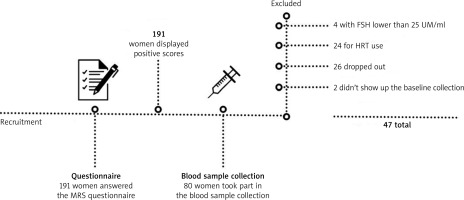

A total of 47 menopausal women participated in the study, aged 53.21 ±3.65 years, range 40–59 years, in a southern Brazilian city. The women were invited to the study through radio announcements, internet, and social networks (Facebook, WhatsApp, e-mail), the University’s website, TV, and printed media. Menopause is classified as starting with the last menstrual period, followed by one uninterrupted year of no menstruation, and for the current study, the 6-year time frame, according to the National Consensus on Menopause [18], called precocious post-menopause, was utilised.

The eligibility criteria were as follows: 1) Inclusion criteria: age 40–59 years, with positive score on the menopause rating scale (MRS) questionnaire [19], and FSH levels equal to or greater than 25 IU/ml [18]; 2) Exclusion criteria: Women who practiced CT and/or jazz dance with a cut-off time of 3 months prior to the start of the study, women who use or will use any type of hormone replacement therapy, women who are in late post-menopause (amenorrhoea over 6 years), and women who use wheelchairs, have heart problems, a history of neurological and/or musculoskeletal diseases or who have any health condition that prevents them from performing physical exercises (Fig. 1).

Randomisation

The randomisation process was performed by a researcher with no ties to the research. She received a sealed envelope with the participants’ names for the group allocations. In this way, the randomisation was carried out 1 : 1, secretly, utilising a computer program (www.randomization.com), which divided the participants into: concurrent training intervention group (CTIG) (n = 23), and CG (n = 24). In the CTIG, a CT protocol was applied for 4 months [20], while the CG received monthly phone contact (on the seventh day of each month) to encourage them to maintain their daily activities and verify whether there were any changes in their physical exercise practices, to confirm that no significant changes had occurred.

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation was performed a priori using G*Power 3.1.9.228 software, and the primary outcome chosen was sexual function, based on a randomised clinical trial conducted with menopausal women [21]. The calculation adopted an α = 0.05, moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.384), test power of 95%, and significance level of 5%. The analysis was carried out using 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures for comparative analysis between factors. Accounting for a potential 5% loss in the sample, 12 women were allocated to each of the 2 groups (CG and CTIG), totalling 24 women.

Study instruments

Sociodemographic and clinical profile: This form was created by the researchers with questions related to age, marital status, education, economic level, the presence of clinically diagnosed pre-existing conditions, and smoking habits. The economic level was determined using the criteria established by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics [22], which classifies the population into economic strata A, B, C, D, or E based on the average monthly family income. Specifically, class A (above 20 minimum wages), class B (10–20 minimum wages), class C (4–10 minimum wa-ges), class D (2–4 minimum wages), and class E (up to 2 minimum wages). The reference value for the minimum wage was based on the 2022 rate of R$1,212. Clinical information was obtained through a questionnaire comprising questions about menopausal age, engagement in sexual activity, type of menopause (surgical or natural), a history of hysterectomy or bilateral oophorectomy, and contraceptive usage.

Menopausal symptoms were assessed using the MRS – a menopause assessment scale developed in Germany and validated in Brazil [19]. The scale consists of 11 questions that are evaluated on a scale from 0 (absence of symptoms) to 4 (highest severity), distributed across 3 domains: somatic, psychological, and urogenital symptoms. To observe the overall reported intensity, a categorisation was established based on the severity of domain symptoms: absent or occasional (0–4 points), mild (5–8 points), moderate (9–15 points), or severe symptoms (16 points). The total score ranges from 0 (asymptomatic) to 44 (highest level of complaints). Within the symptom categories, minimum/maximum scores can vary across the 3 dimensions. For psychological symptoms: 0–16 points (4 symptoms: depressed mood, irritability, anxiety, exhaustion); for somatic-vegetative symptoms: 0–16 points (4 symptoms: sweating/flushes, cardiac complaints, sleep disturbances, joint and muscle complaints); and for urogenital symptoms: 0–12 points (3 symptoms: sexual problems, urinary complaints, vaginal dryness). The test-retest correlation coefficient (Pearson’s correlation) was 0.9 for the total score across all countries combined, indicating high internal consistency and confirming good measurement quality [23].

Depression was measured using – the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) [24], which aims to identify (probable) cases of mild anxiety disorder (MAD) and/or depressive symptoms in non-clinical populations. The instrument was validated in Brazil [25]. It demonstrated an internal consistency of 0.68 for anxiety and 0.77 for depression. The scale consists of 14 items divi- ded into 2 subscales: HADS-anxiety, comprising 7 questions for the diagnosis of MAD (odd-numbered items), and HADS-depression, including another 7 questions for mild depressive disorder (even-numbered items). Responses are scored on a scale ranging 0–3 points (from not present to very frequent), with a maximum score of 21 points for each subscale. The cut-off scores, based on the literature, are ≥ 9 points for each disorder (0–8: no anxiety/no depressive symptoms; ≥ 9: indicates anxiety/depressive symptoms).

Sexual function was assessed using the – female sexual function index (FSFI) [26], translated from Portuguese, culturally adapted and validated to assess the FSFI in Brazilian women [27]. This brief questionnaire is specific and multidimensional, and comprises 19 self-administered questions, which assess 6 domains of female sexual response: arousal, orgasm, pain, satisfaction, sexual desire, and vaginal lubrication. Response options are rated 0–5, indicating the occurrence of the questioned function. Scores are inverted for questions related to pain. Each FSFI domain provides scores that, when summed, are multiplied by a factor that equalises the influence of each domain, resulting in a total score. Domain scores range 0–6 (except for desire: minimum 1.2 and satisfaction: minimum 0.8), and the total score ranges 2–36. A higher final score indicates better sexual function. The overall test-retest reliability coefficients were high for each domain (r = 0.79 to 0.86), and a strong internal consistency was observed (Cronbach’s α values of 0.82 and above) [26].

The aging perspective – the Sheppard inventory, adapted to Portuguese and validated for Brazil [28], is designed to estimate attitudes towards aging. The instrument consists of 20 questions, divided into 4 subgroups, to assess the respondent’s opinions regarding the following:

the possibility of being happy in old age,

whether old age implies dependence, death, and loneliness,

whether it is better to die young than to experience the anguish and loneliness of old age,

whether old age can bring feelings of integrity.

The scales are organised to assess both positive domains (such as self-esteem, coping, and social support) and negative domains (such as anxiety, depression, stress, and relationship difficulties). Through the scores, it is possible to determine whether participants have a positive or negative perception of finitude (prevalence): the higher the score, the greater the presence of the symptom.

Data collection

Baseline data collection took place in February 2022, following the signing of a informed consent form. Post-intervention data collection occurred after 16 weeks, in July 2022. During these sessions, the instruments were individually dispensed in a self- administered online format via Google Forms, with an average duration of 20 minutes per session. Blinding of the study was not feasible, given that it involved an exercise intervention, so both participants and researchers were aware of the type of exercise being administered.

Intervention protocol

The concurrent training utilised in the interventions spanned a duration of 4 months, following the protocol [20]. This protocol was established based on existing evidence of CT for menopausal women [29, 30] and in accordance with the recommendations of Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials [31]. During the first 2 months of the protocol, the initial 30 minutes comprised aerobic training, followed by 30 minutes of resistance training. In the subsequent 2 months, the aerobic training duration was reduced to 20 minutes, followed by 40 minutes of resistance training. The training sessions were conducted 3 times a week, lasting 60 minutes each, with a progressive intensity. Additionally, study participants were required to attend a minimum of 75% of the sessions to be included in the study.

Aerobic training

The aerobic training was regulated in accordance with the guidelines of the American College of Sports Medicine (2018) and was conducted on a treadmill. Initially, the training intensity was set at 60% of the maximum heart rate, with the possibility of later increasing it to 90%, monitored using a digital pulse oximeter. The effort intensity was tracked using the Borg scale [33], ranging from 0 (nothing at all) to 10 (extremely strong). Table 1 outlines the progression of aerobic training over the 16 weeks

Table 1

Specifications of aerobic training in the 4 months of intervention

Resistance training

The resistance training followed the guidelines of the American College of Sports Medicine (2018). In the first month, adaptation to the training was conducted, aiming to gradually increase the intensity safely throughout the intervention. Figure 2 illustrates the progression of some of the exercises implemented during the intervention. Table 2 outlines the progression of resistance training over the 16 weeks.

Fig. 2

Illustration of the progression of some exercises used in the concurrent training intervention

Table 2

Resistance training specification in the 4 months of intervention

Adherence

The adherence rate of participants in the intervention groups was calculated as follows: number of attended sessions/48 planned sessions 100× [34]. The researcher recorded the number of attended sessions during the intervention period. Study participants who did not achieve a 75% attendance rate were contacted for post-intervention data collection to analyse the effect of the exercise intervention in these participants. This analysis was carried out following the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle.

Statistical analysis

The data were tabulated and stored in an Excel spreadsheet, and subsequently analysed using IBM SPSS software (version 20.0). Descriptive statistics were computed, including simple frequencies for categorical variables, and measures of central tendency and dispersion for numerical variables. The normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The comparison of categorical variables was performed using the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. To compare the groups (CTIG and CG) concerning numerical variables before and after the 16-week intervention, a 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures and the Sidak comparison test were employed. Finally, to analyse the effect size, Cohen’s d cut-off points were adopted, classified as follows: 0.10 (small effect), 0.30 (medium effect), and 0.50 (large effect). The significance level was set at 5%.

Results

A total of 23 women were included in the CTIG, of whom 7 did not meet the minimum attendance requirement of 75% (Fig. 3). These participants were analysed according to the ITT principle.

Fig. 3

Consolidated standards of reporting trials flowchart of participant recruitment

FSH – follicle-stimulating hormone, HRT – hormone replecement therapy, MRS – menopause rating scale

The baseline characteristics can be found in Table 3, presented according to the randomised groups. The groups are homogeneous, with income being the only statistically significant difference observed between the groups (p = 0.016).

Table 3

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants at baseline according to groups

Table 4 presents the results regarding the outcomes of menopausal symptoms, depressive symptoms, sexual function, and perspective on aging using an ITT analysis. No significant intergroup effects were found in any of the analysed variables. However, a significant intragroup improvement was observed in all menopausal symptoms, specifically somatic symptoms (p = 0.001), psychological symptoms (p = 0.001), urogenital symptoms (p = 0.001), and total symptoms (p = 0.001). Additionally, the ITT analysis also showed improvement in depressive symptoms (p = 0.019), an increase in sexual desire (p = 0.038), and a reduction in loneliness (p = 0.031).

Table 4

Comparison of mean outcome scores, pre and post-intervention in the intentioan-to-treat analysis (n = 22)

These results indicate that, although no significant differences were observed between groups, there was a consistent improvement within the intervention group, suggesting that physical training had a positive impact on menopausal symptoms and related emotional aspects, such as depression and loneliness. The improvement in sexual desire also suggests a positive effect of the intervention on participants’ sexual quality of life.

The analysis by protocol can be found in Table 5. In terms of the intragroup results, there was an improvement in menopausal symptoms in all domains of MRS, specifically somatic symptoms (p = 0.001), psychological symptoms (p = 0.001), urogenital symptoms (p = 0.001), and total score (p = 0.001), as well as a reduction in depressive symptoms (p = 0.016). Additionally, improvements were observed in sexual function across 4 domains, including desire (p = 0.007), lubrication (p = 0.024), satisfaction (p = 0.030), and the overall sexual function score (p = 0.022). Furthermore, concerning the aspect of ‘finitude’, there was a significant improvement between groups in the domain of happiness (p = 0.046).

Table 5

Comparison of mean outcome scores, pre- and post-intervention, protocol analysis (n = 15)

These results suggest that physical training had a substantial positive impact on the participants’ quality of life, with significant improvements in physical, psychological, and emotional aspects. The reduction in menopausal and depressive symptoms, along with improvements in sexual function and the perception of happiness, indicate that the intervention was effective across various domains of women’s health during menopause. While improvements were significant within the intervention group, it is important to note that the analysis found no significant differences between the groups, which may suggest the need for further studies to confirm these findings.

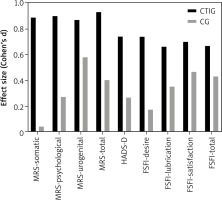

Furthermore, the effect size (Fig. 4) within the CTIG group, compared to the CG is highlighted, in the somatic symptoms (d = 0.89), psychological symptoms (d = 0.90), urogenital symptoms (d = 0.87), and total symptoms (d = 0.93) of menopause. Additionally, changes were observed in depressive symptoms (d = 0.74) and in sexual function, desire (d = 0.74), lubrication (d = 0.66), satisfaction (d = 0.70), and total (d = 0.60), indicating that the CT had a significant effect on these variables.

Fig. 4

Effect size of the concurrent training intervention group group, compared to the control group

CG – control group, CTIG – concurrent training intervention group, FSFI – female sexual function index, HADS-D – anxiety and depression scale, MRS – menopau se rating scale

These results highlight the substantial impact of the intervention, with large effect sizes across various domains of menopausal symptoms and sexual function, suggesting that CT has a considerable effect on improving the physical and emotional well-being of women in menopause. The particularly high effect sizes in symptoms such as psychological and somatic (d > 0.80) emphasise the relevance of CT in alleviating these aspects, which are so prevalent in the menopausal experience. Additionally, the significant improvement in sexual function, with moderate to large effect sizes, suggests that CT may have a positive impact on the participants’ sexual function.

Discussion

The current study aimed to analyse the effect of CT after 4 months of intervention compared to the CG on menopausal symptomatology, depression symptoms, sexual function, and perspectives on aging in menopausal women. The results suggest a positive effect of CT on menopausal symptoms, depressive symptoms, 4 aspects of sexual function (desire, lubrication, satisfaction, and total), as well as the domains of happiness and loneliness in the perspective on aging.

The literature supports that hormonal alterations occurring during menopause are linked to inconvenient metabolic variations, such as abdominal fat accumulation and vasomotor symptoms, which in turn affect sleep and can lead to mood alterations, impacting quality of life [35]. The findings of this study demonstrate a positive intragroup effect of CT on somatic, psychological, urogenital, and total menopausal symptoms in both the ITT and protocol analyses. These findings align with the results of another randomized clinical trial involving a resistance training intervention, which also proved effective in reducing vasomotor symptoms. Other studies have also shown improvements in arterial stiffness, muscle strength, and body composition [29, 30, 36]. Furthermore, aerobic training has demonstrated effectiveness, particularly in psychological symptoms, reducing depression, anxiety, and improving sleep quality [37, 38]. Endurance exercise has proven to be an effective means to attenuate and protect against adverse metabolic alterations in pre-, peri-, and postmenopausal periods [39]. In the current study, CT appears to be an important ally in alleviating menopausal symptoms.

When analysing depressive symptoms in this study, the group that performed the CT intervention, both in the ITT and protocol analyses, demonstrated intragroup improvement. This finding aligns with a Finnish cohort study that examined the mental well-being of women in pre-, peri-, and postmenopausal stages, where wo-men with high levels of physical fitness less frequently experienced depressive symptoms [40]. In another intervention study, aerobic training proved effective in improving anxiety and depression in menopausal wo-men, as a predictive method for enhancing their mental health [37]. Fluctuating and declining oestrogen levels during menopause can lead to negative psychological effects, increasing the risk of depression and anxiety [41]. Therefore, adopting physical exercise as an alternative for psychological relief is important for women. Concurrent training appears to help in preventing and alleviating depressive symptoms, making it a valuable ally in treating menopausal symptomatology.

Regarding sexual function, the CT group exhibited intragroup improvement in desire, lubrication, satisfaction, and total aspects. The intention-to-treat analysis demonstrated improvement only in desire, suggesting that intervention duration may play a role in achieving better benefits. Our results align with an Italian cross-sectional study, which showed that physically active women scored higher in various domains of the FSFI, including desire, arousal, and lubrication, compared to sedentary women [42]. A Brazilian study found that inactive women had a higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction (78.9%) compared to active (57.6%) and moderately active (66.7%) women, highlighting physical activity as a protective factor against sexual dysfunction [43]. Female sexuality is multifaceted and complex, and during menopause, sexual function worsens due to various factors of biological, psychological, relational, and sociocultural origin. Physical exercise is a modifiable factor that can improve the lives of these women [44].

Lastly, in terms of the aging perspective, the menopause transition marks a significant and natural process of inevitable change towards aging [45]. The current study sought to assess whether CT could change women’s perspectives on aging. It was found that the CT group exhibited intergroup improvement in the aspect of happiness, while in the ITT analysis, intragroup improvement was observed in the aspect of loneliness. Other studies with menopausal women identified that increased physical fitness leads to improved self-esteem and positive affect, and that improvements in affect contribute to enhanced quality of life [40, 46]. Interacting with other women may have influenced this factor, as engaging in enjoyable activities together can serve as a motivating factor for happiness and reducing loneliness. However, further studies are needed to directly verify the efficacy of physical exercise in the aging perspective within this population. Furthermore, this variable is challenging to analyse due to the numerous peculiarities and life events experienced by these women, including menopause, aging, retirement for some, empty nest syndrome, separation from partners, body changes, and more [47].

The strengths of this study include the CT intervention protocol specifically designed and published for menopausal women, which was shown to be safe, with no complications or falls, and which achieved high participant adherence (88.75%). Even among participants who did not adhere to the protocol’s determined 75% attendance rate, CT still demonstrated effectiveness, yielding significant results. Additionally, we mention the inclusion of FSH as a criterion, to confirm that the sample was indeed in menopause, the 16-week intervention duration, and the ITT analysis, meeting CONSORT criteria.

One limitation to note is the scarcity of studies approaching this topic from an aging perspective, making it difficult to compare our findings with existing research. Additionally, the lack of blinding in the analyses, due to limited human resources, is another constraint. Although blinding was not possible due to the nature of the exercise intervention, it is important to note that both participants and researchers were aware of the training being administered, which may have influenced perceptions and responses, potentially introducing bias into the results. However, objective measures and validated questionnaires were used to minimize this impact.

Despite these limitations, our results highlight the need for further scientific investigation into the psychological and physical aspects of this population. Expanding research in this area would enhance the reliability and scientific credibility of CT as a non-pharmacological intervention for menopausal symptoms, depression, sexual function, and perceptions of finitude.

Conclusions

Concurrent training was shown to be an effective non-pharmacological therapy, providing benefits in menopausal symptomatology (somatic, psychological, urogenital, and total), as well as in depressive symptoms, both in the ITT and CT groups. The 4-month practice duration appears to be significant, with the CT group achieving better results in 4 domains of sexual function (desire, lubrication, satisfaction, and total score) and in the aging perspective, specifically in the domain of happiness. In contrast, the ITT analysis showed improvement only in the desire domain of sexual function and loneliness in the aging perspective. These findings underscore the effectiveness and importance of conducting interventions with an appropriate duration, frequency, and intensity.