Introduction

HIV infection remains a critical global public health challenge – not only due to its clinical and epidemiological implications, but also because of its profound social, economic, and cultural dimensions [1]. Although biomedical advances have improved the quality of life for people living with HIV, eradicating the virus requires strategies that extend beyond clinical care, particularly those addressing the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of the general population.

Middle-aged women constitute a group traditionally excluded from HIV/AIDS prevention campaigns, despite many remaining sexually active and undergoing major life transitions such as divorce, the initiation of new relationships, or widowhood [2]. In Peru, recent studies indicate that this population remains vulnerable due to the persistence of myths, low risk perception, and limited access to information – especially in rural areas [3].

Access to information, sexual health services, and prevention strategies is significantly shaped by geographic and social environments. Structural barriers such as geographic isolation, low educational attainment, and specific cultural or religious practices hinder the adoption of preventive behaviors, increasing vulnerability to HIV infection [4, 5].

In low- and middle-income countries, social and economic inequalities are consistently associated with lower levels of knowledge about HIV transmission and prevention, particularly in rural areas where sexual health services are less accessible [6, 7]. Misconceptions such as the belief that HIV can be transmitted through mosquito bites persist even in urban settings, highlighting a widespread informational gap [3].

Moreover, the quality of life for individuals living with HIV depends not only on effective clinical management, but also on socio-emotional and cultural factors often overlooked by conventional public health approaches [8]. One study conducted among rural Peruvian women found that those using natural contraceptive methods had lower levels of HIV-related knowledge and held more misconceptions than their urban counterparts, particularly those using barrier methods [3].

International evidence further demonstrates that cultural and personal beliefs significantly influence adherence to antiretroviral treatment, with implications for both prevention and clinical outcomes [9]. These findings underscore the urgency of designing culturally contextualized interventions tailored to women’s specific realities, rather than relying on universal approaches. Recent qualitative studies have emphasized that addressing cultural and religious determinants is critical for the success of prevention strategies [4, 9].

In this context, the present study aims to assess and compare HIV/AIDS-related knowledge and beliefs among Peruvian women aged 40 to 49, focusing on urban–rural differences. Although approaching the end of reproductive life, many women in this age group remain sexually active, often experience significant relational and life transitions, and continue to be overlooked in sexual health promotion strategies.

Material and methods

Study design and data source

A quantitative, analytical, cross-sectional study was conducted using microdata from the 2024 Demographic and Family Health Survey (ENDES), carried out by the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics of Peru (INEI), a publicly available and nationally representative survey [10]. This survey is representative at the national, departmental, urban, and rural levels and is based on a probabilistic, two-stage, stratified, and cluster sampling design.

Study population and sample

The database included 37,117 records of women of reproductive age. For this study, we included women aged 40 to 49 years with complete information who resided in either urban or rural areas of Peru. Based on these criteria, the final sample consisted of 6,314 women: 4,176 urban and 2,138 rural residents.

Study variables

Sociodemographic characteristics were analyzed, including age (V013) and place of residence (V025), as well as educational level (V106), wealth index (V190), and sexual activity in the past year (V766B). These variables were recoded to facilitate interpretation and comparability across subgroups. Two variables served as indirect indicators of access to sexual health information: having received information about AIDS (V751) and about other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (V785). Variables related to knowledge of HIV testing facilities were also included and categorised by type of establishment according to the respondent’s answer. Public facilities comprised SIS public hospitals, which primarily provide free care to uninsured individuals through the Comprehensive Health System, and EsSalud hospitals, which serve formally employed individuals and their dependents under the social-security scheme. Additional categories were primary health centres, peripheral health posts, and private clinics.

Variables assessing knowledge and beliefs about HIV/AIDS were treated individually as dichotomous categorical variables following recoding. Negative responses included “No” and “Does not know”, while only “Yes” was considered affirmative. These variables encompassed knowledge of vertical transmission (V774A, V774B, V774C), perceived risk from asymptomatic individuals (V756), and both preventive and erroneous beliefs (V754BP, V754CP, V754DP, V754JP), among others. One misconception (V754JP) was reverse-coded to ensure interpretative consistency, so that higher values reflected accurate knowledge across all items.

An unweighted additive index was constructed to summarize the number of accurate responses regarding HIV/AIDS knowledge and beliefs. The index included nine dichotomous items, including V751 as a proxy for exposure to information. The resulting score ranged from 0 to 9, with higher values indicating greater overall knowledge and more accurate beliefs. This approach provided a standardized summary measure in the absence of validated weights and is consistent with previous DHS-based research.

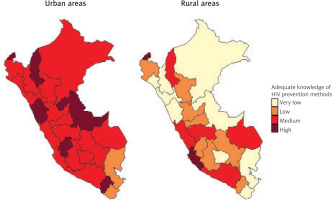

For geographic representation, the index was categorized into four qualitative levels based on observed percentiles: “Very low” (≤ 4.8), “Low” (> 4.8 to ≤ 5.4), “Medium” (> 5.4 to ≤ 6.0), and “High” (> 6.0). This classification facilitated clearer visualization of territorial disparities across departments in urban and rural areas.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Stata v17. The complex sampling design was specified using the svyset command, with primary sampling units (V001), strata (V022), and the adjusted sampling weight (V005/1,000,000). Databases were merged using the CASEID variable. Absolute frequencies and weighted proportions were described, along with 95% confidence intervals, using the svy suite of commands and options. Associations between area of residence (urban vs. rural) and key variables were assessed using the chi-squared test adjusted for complex design (Rao-Scott test).

For geospatial analysis, weighted departmental averages by area were calculated using the collapse command in Stata. These results were then exported to RStudio (version 2024.12.1) for the creation of comparative maps of urban and rural areas. The sf, ggplot2, and patchwork packages were used to visualize regional differences in the level of accurate knowledge and beliefs about HIV/AIDS.

Ethical considerations

This study was based on the analysis of publicly available secondary data from the 2024 Demographic and Family Health Survey (ENDES), which is anonymized and does not contain personally identifiable information. As the analysis posed no risk to participants and did not involve direct contact with human subjects, formal ethical approval from a research ethics committee was not required. The use of these data complies with national and international ethical standards for secondary data analysis.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Age distribution was similar between urban and rural areas (p = 0.256), while no significant differences were found in educational level or wealth index between the two settings. Regarding sexual practices, a higher percentage of rural women reported having had sexual intercourse in the past year (83.9%) compared to urban women (75.1%) (p < 0.001). Rural women also showed lower exposure to health information compared to their urban counterparts (p < 0.001; Table 1).

Table 1

Sociodemographic characteristics and exposure to health information among Peruvian women aged 40–49, by area of residence (urban vs. rural)

Knowledge about HIV/AIDS

Regarding the perception that a seemingly healthy person can be infected with HIV, 81.0% of urban women responded affirmatively, compared to 62.4% of rural women (p < 0.001). Similarly, knowledge about HIV transmission during pregnancy was higher in urban areas (52.5%) than in rural ones (32.2%). Awareness of possible transmission during childbirth was also more frequent in urban areas (20.7%) compared to rural ones (11.7%). In contrast, knowledge about transmission through breastfeeding was similar in both areas (p = 0.100; Table 2).

Table 2

Knowledge about HIV/AIDS transmission among Peruvian women aged 40–49, by area of residence

Preventive and misconception-based beliefs about HIV/AIDS

Regarding sexual abstinence as a preventive strategy, 79.0% of urban women and 71.2% of rural women recognized it as effective (p < 0.001). Similarly, 82.3% of urban respondents affirmed that consistent condom use reduces the risk of infection, compared to 73.1% in rural areas. Additionally, 90.1% of urban women and 76.3% of rural women believed that having only one sexual partner reduces the risk of HIV – the largest observed difference in preventive beliefs between areas (p < 0.001). Conversely, the belief that HIV can be transmitted by mosquito bites was significantly more prevalent among rural women (p < 0.001; Table 3).

Table 3

Beliefs about HIV/AIDS among women aged 40–49, by area of residence

Known sources for HIV testing

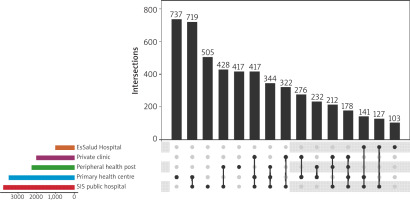

The five most frequently known sources for HIV testing were SIS public hospitals (3,772 women), primary health centres (3,469), peripheral health posts (2,249), private clinics (2,018), and EsSalud hospitals (996). The most common combinations of known sources were SIS public hospital + primary health centre (719 women), SIS public hospital + primary health centre + private clinic (417), and SIS public hospital + primary health centre + peripheral health post (344) (Figure 1).

Geographic representation of accurate HIV/AIDS knowledge and beliefs

Geographic analysis of the composite index of accurate knowledge and beliefs about HIV/AIDS revealed a clear trend: urban areas had a higher average score than rural areas. This gap was especially pronounced in the central highlands and Amazon regions, where many rural zones fell into the “very low” or “low” categories.

Despite this general trend, some exceptions were observed. For instance, in certain departments of the northern coast, such as Tumbes, both urban and rural areas reached “high” levels. Furthermore, in regions like Ica, rural areas even outperformed their urban counterparts. These contrasts reflect territorial heterogeneity that should be considered when designing context-specific intervention strategies (Figure 2).

Discussion

This study reveals notable findings regarding the level of knowledge and beliefs about HIV/AIDS among Peruvian women aged 40 to 49, highlighting disparities based on area of residence. Although over 75% of participants reported being sexually active in the past year, significant gaps in knowledge about HIV transmission modes were identified, particularly in rural areas. Awareness of vertical transmission, including childbirth and breastfeeding, was limited among most women. This represents a major gap in perinatal HIV prevention.

These results are consistent with studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries, where women in rural areas tend to have lower levels of HIV knowledge, often due to structural and educational limitations [6, 11]. Likewise, widespread unawareness of transmission during pregnancy and breastfeeding aligns with findings from African and Asian studies reporting persistent misconceptions among adult women, even those with prior contact with healthcare services [12, 13]. Despite decades of prevention campaigns, misconceptions such as the belief that HIV can be transmitted through mosquito bites persist. Nationally, 46.2% of women aged 40 to 49 endorsed this erroneous belief, with a higher prevalence in rural areas (56.5%) compared to urban areas (43.9%). These findings mirror patterns reported in countries such as Nigeria and Sri Lanka [14, 15], where misinformation and enduring myths continue to undermine preventive behaviors.

Regarding access to HIV testing, there was a clear preference for public services such as SIS public hospitals and primary health centres, which were the most frequently recognised sources of diagnosis. This pattern suggests a degree of trust and accessibility associated with state-run institutions. In contrast, EsSalud hospitals were mentioned less often, especially in rural areas where geographic and administrative barriers may limit awareness and access. These findings point to persistent inequalities in knowledge about testing options, particularly in settings with fewer healthcare resources [16, 17].

Thematic maps revealed clear urban–rural differences in average scores, with pockets of divergence that break the national pattern. In a few coastal and highland areas, rural scores surpassed those of their urban counterparts, whereas in several jungle and Andean regions the gap was wider in favour of urban areas. Notably, many highland departments – especially in rural settings – consistently showed the lowest levels of adequate knowledge and beliefs, in some cases not exceeding the “Low” category on the scoring scale. This spatial heterogeneity likely reflects uneven coverage of educational and sexual-health programmes, a pattern also documented by geospatial studies in Ethiopia and Cameroon [18, 19].

These findings carry important implications for healthcare professionals, particularly those in primary care. Health teams must stay continuously updated on HIV/AIDS content and be aware of the persistence of myths among age groups traditionally excluded from educational campaigns.

Community education efforts should be directed not only toward youth but also toward older adult women, using communication that is clear, culturally sensitive, and non-judgmental. Examples include bilingual radio spots in Quechua and Shipibo-Konibo, brief “telenovela” segments on local television stations, and WhatsApp micro-videos distributed through women’s clubs. Staff should be trained to provide sexual-health counselling tailored to this life stage, promote gender-sensitive prevention, and identify information gaps during routine consultations. Implementing quarterly refresher workshops such as the eight-hour HIV module offered by the Peruvian College of Midwives can help standardise provider competencies.

These findings call for a restructuring of information, education, and communication (IEC) strategies, which have traditionally focused on youth or women of reproductive age up to 35. Women over 40 remain sexually active and, as this study shows, may be misinformed or influenced by erroneous beliefs. They must be included as a target group in educational interventions, particularly since this stage of life often involves changes in sexual and marital relationships, increasing vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections.

Barriers such as stigma, lack of trust in the health system confidentiality, and assumptions about sexual inactivity in certain groups may limit the effectiveness of current campaigns [20, 21]. The low condom use among older women, linked to low perceived risk and negative attitudes toward HIV, has also been documented in countries including China and the United States [22, 23]. These findings highlight the need for culturally and generationally appropriate strategies. Educational campaigns should include middle-aged women, use digital tools to broaden reach, and ensure healthcare providers are trained to offer inclusive, stigma-free counseling.

Interventions should also acknowledge the key role of formal education in reducing stigma and improving knowledge. Integrating HIV content into the Ministry of Education’s Programa de Alfabetización para Adultos and partnering with night schools can reach women who did not complete basic schooling. Evidence from Pakistan, South Africa, and Somalia [24–26] shows that such school-linked strategies can significantly enhance HIV literacy among older age groups.

This study’s strengths include the use of a nationally representative database and an analytical approach that combines complex statistical methods with geographic comparisons. The decision to focus on women aged 40 to 49, still considered part of the reproductive age group according to WHO criteria, was based on their biological potential for pregnancy and increased vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections at this life stage. Their inclusion also addresses a notable evidence gap, as this age group is typically underrepresented in national HIV data.

Nevertheless, it presents limitations inherent to secondary data analysis, such as the inability to explore contextual or qualitative factors that may influence respondents’ answers. Additionally, the cross-sectional design does not allow for causal inferences. Since the data are based on self-reports, the results may be affected by recall bias or social desirability bias, particularly in relation to topics such as sexuality and HIV-related stigma. The absence of certain potentially relevant variables, including characteristics of sexual partners, contraceptive use, and exposure to specific sources of information, also limited the analytical depth. Future studies should incorporate mixed-methods designs to contextualise these quantitative findings.

Conclusions

This study underscores the urgent need to reframe HIV/AIDS education strategies in Peru, particularly for women aged 40 to 49, who remain outside the focus of most current interventions. The disparities identified reflect not only informational gaps, but also structural and cultural barriers that continue to shape risk perception and access to care.

To move toward more inclusive public health action, it is essential to expand the scope of prevention campaigns, ensuring that messaging and services address the realities of middle-aged women across diverse geographic settings. Strengthening the role of primary care teams in this effort will be critical for achieving equity in sexual health education and HIV prevention.