Complex lymphatic malformations (complex LM) include generalized lymphatic anomaly (GLA), Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis (KLA), Gorham-Stout disease (GSD) and central conducting lymphatic anomaly (CCLA) [1]. All of the aforementioned conditions overlap in clinical and radiological signs. Lymphatic malformations occur as sporadic, and in most of them there are disturbances in components of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. On a molecular basis, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-C) is a critical regulator of lymphangiogenesis. By activating its receptor VEGFR-3, it initiates a signaling process in cells that promotes their growth and differentiation [2]. High concentrations of VEGF-C have been observed in GSD patients [3].

Generalized lymphatic anomaly is a type of lymphatic malformation with no clear etiology. It appears to have genetic, developmental, and environmental background. There have been reports indicating that trauma may induce lymphatic malformation occurrence. Somatic NRAS mutations and disturbances in the RAS/MAPK pathway have been suggested as possible genetic causes in GLA [4].

Differential diagnosis between all types of complex LM is difficult, but there are distinguishing features. Patients with GLA typically have involvement of multiple organs, presenting with pleural effusion, mediastinal mass, ascites, peripheral lymphedema, bone changes, and multiple cystic splenic lesions. These manifestations are more common in GLA than in GSD. KLA, a subtype of GLA, is characterized by a more severe clinical course with thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, and bleeding [4].

Pathological examination in GLA typically reveals dilated and malformed lymphatic channels. Furthermore, in KLA, kaposiform hemosiderotic spindle-shaped lymphatic endothelial cells are a distinctive hallmark. In contrast, the characteristic pathological features of GSD include diffuse lymphatic vessel proliferation, progressive osteolysis, and the activation of osteoclasts [4].

Multiple, nonprogressive lytic bone changes present in the medullary cavity, located in the skull, thoracic, and lumbar spine, allow for the distinction between GLA and GSD. In the latter, osteolytic changes primarily affect the appendicular skeleton, ribs, cranium, clavicle, and cervical spine and are progressive, leading to involution of cortical bone and subsequently causing pain or fractures [4].

A 12-year-old boy was referred to our hospital due to bilateral pleural effusion. The patient had experienced a compression fracture of the thoracic vertebra Th9 about one year before admission (from falling out of a tree), which was managed conservatively with an orthopedic corset. After completing his physiotherapy, a follow-up chest X-ray revealed bilateral fluid accumulation in the pleural cavity and reduced lung volume. The patient had been experiencing dyspnea, weight loss (8 kg in 8 months), and decreased exercise tolerance for a few months. Upon admission, compared to clinical findings he exhibited circulatory and respiratory efficiency, which suggests a chronic process. In the Emergency Department, a chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed massive bilateral pleural effusion (up to 10 cm thick), causing compression and anterior displacement of the lungs, as well as pathological thinning of the lower cervical and all thoracic vertebrae and adjacent rib segments (II and III/second and third rib on the left side, II to VII/second to seventh rib on the right side). Laboratory tests showed low proteins, lipids and fibrinogen serum levels and increased D-dimers. Bilateral drainage of the pleural cavities was performed, with an intraoperative drainage volume of 2300 ml of the lymph-like fluid on the left side and 2100 ml on the right side. In postoperative period due to the large amount of drained lymph and consequential loss of protein and electrolyte imbalance, periodic drainage was used. Additionally, the patient predominantly complained of inflammation in the oral cavity and pharynx, which was effectively managed with local treatment using an antibiotic and steroid-containing mouthwash suspension/solution, leading to prompt resolution.

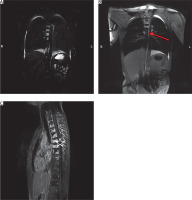

During hospitalization, inflammatory parameters remained normal, pleural fluid cultures were negative. The patient received antibiotic and antifungal prophylaxis, parenteral nutrition with reduced fat content, supplementation with medium-chain triglycerides (MCT), and oral replacement of protein supplements and vitamins. Despite this treatment, significant drainage from the pleural cavities persisted. Therefore, further diagnostics were pursued, including dynamic MR lymphography with contrast administration to the lymph nodes (Figure 1). It showed, beside pleural effusion, a heterogeneous remodeling of the thoracic vertebrae (bodies and spinous processes with edema and enhancement after contrast administration). The thoracic duct was barely visible above Th9, and dilated lymphatic vessels were observed in the periaortic area and thoracic vertebral bodies, along with lymphatic fistulas to the pleural cavity on both sides in the neighborhood of the main bronchi. Among other radiological findings, small cystic lesions were identified in the spleen (MRI), along with a suspected choroidal fissure cyst and features indicative of Chiari malformation type 1 (CT).

Figure 1

MR lymphography before and after intranodal contrast administration. Thoracic duct is visible (red arrow). Delay enhancement of the vertebral bodies (asterisk)

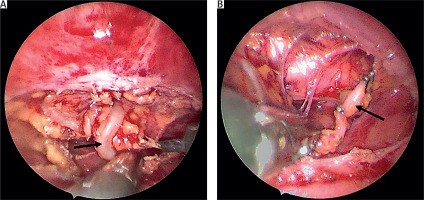

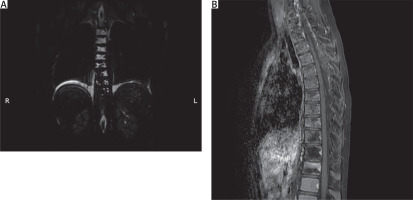

Based on the clinical and radiological findings, a generalized lymphatic anomaly was suspected. In accordance with published research papers, sirolimus (rapamycin) therapy was initiated. After the introduction of sirolimus, the pleural fluid became bloody, and the patient developed anemia that required a blood transfusion (three times). Due to substantial drainage the patient underwent a thoracic duct partial resection and maintained drainage. During the right-sided thoracoscopy, the thoracic duct was identified and dissected below the vena azygos towards the diaphragm. The thoracic duct was then clipped on both ends, along with some of its larger side branches, and then resected (Figure 2). After surgery a decreased amount of lymph was observed. Sirolimus therapy was continued after the procedure. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and biochemical parameters normalized (Figures 3 A, B). In total, drainage was maintained for 58 days, including 45 days after TD closure. Following hospitalization, the patient remained under constant outpatient supervision. The presence of the fluid in the pleural cavities was monitored by ultrasound examination; only a minimal amount of the fluid was visible on both sides. Continuous measurements of sirolimus concentration were performed, and periodically the concentrations were slightly below the norm, so the dose was modified to achieve therapeutic concentration ranges. Six months after hospitalization, a follow-up magnetic resonance imaging examination was performed. There was no deterioration, a small amount of the fluid was still present in both pleural cavities, and the appearance of the bone structures remained stable (Figure 4). Seven months after being discharged, he suffered a pathological fracture of the thoracic vertebrae (Th6-7) due to a fall but was again treated conservatively with a Jewett brace, resulting in good outcomes. To date, the patient’s clinical condition remains stable, with no pulmonary issues or treatment side effects. Therefore, a multimodal treatment approach that combines general, surgical, and causal methods has improved the patient’s condition.

Figure 2

Intraoperative images of the thoracic duct (marked with a black arrow). A – Dissected and exposed. B – Clipped

Figure 3

A, B – The charts illustrates the relationship between the volume of the fluid drained from the pleural cavities and the biochemical values (protein) over time. A red arrow indicates the moment of initiating sirolimus therapy and the surgical closure of the thoracic duct (with a 1-day interval)

Figure 4

A – Static MR lymphography. Remodeling of the vertebral body is still visible. No thoracic duct visible. B – Thoracic spine MR after i.v. contrast administration. No enhancement after contrast administration on the sagittal view

There are few publications on the treatment of GLA in children. This condition is a potentially life-threatening disease. The overall mortality rate in complex LM is 20% (17 out of 85), but deaths are related to thoracic lesions [5]. In the pediatric group with thoracic involvement, the mortality rate is 26% (13 out of 50) [5]. Therefore, it requires an appropriate approach.

Based on the available literature, the first-line treatment focuses on symptomatic relief, while the second line attempts causal treatment. Most of the described cases initially focus on treating respiratory complications. Patients with pleural or pericardial lymphatic effusion can be treated with total parenteral nutrition with medium-chain fatty acids, which are distributed mainly in the blood vessels [6]. Octreotide administration is a well-documented treatment for chylous effusion, blocking vascular somatostatin receptors and minimizing lymphatic fluid excretion [7].

Although the above-mentioned approach is well-documented, it appears to be ineffective in the treatment of GLA, at least when used as a standalone therapy. While chemotherapy, interferon or propranolol administration, and radiotherapy have been shown to reduce lymphatic lesions, their use in treating GLA has yielded limited effectiveness [6].

Surgical treatments with proven effectiveness in GLA include effusion drainage and ligation of the lymphatic ducts [6]. Following first-line treatment, causal treatment is essential for stabilizing the patient’s condition, with rapamycin administration being the best-documented option [8]. Rapamycin is an immunosuppressive drug that inactivates mTOR kinase and inhibits lymphangiogenesis [8].

Ozeki et al. radiologically assessed patients with complex LM 6 months after initiating sirolimus therapy. They demonstrated a reduction in lesion size in 50% (10/20) of patients, but complete disappearance of lesions was not observed [9]. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that up to 92% of patients with GLA experienced overall improvement 12 months after initiating sirolimus therapy [10].

Alvarez et al. reported the case of an 8-year-old boy with respiratory and intestinal problems without any inflammatory symptoms but with coagulopathy. Radiological tests showed a mediastinal mass and pleural effusion. A biopsy of the lingula revealed lymphangioma involving the fibrous pleura. Initially, he was treated with corticosteroids, diuretics, and a-interferon. For coagulation disturbances, a trial of aminocaproic acid therapy was unsuccessful, so radiotherapy was administered for the mediastinal mass, followed by anticancer drugs. The patient died 3 months after admission due to multiple organ failure [11].

Fujii et al. presented the case of disseminated intravascular coagulation in a patient with GLA, which was connected to sirolimus administration. A 3-year-old boy treated with pericardial fenestration and thoracic duct ligation for lymphatic effusion due to GLA was asymptomatic until 11 years of age. At that age, pleural lymphatic effusion occurred, and the patient was treated with bilateral drainage. Due to massive effusion, sirolimus treatment was administered. After starting this drug treatment, the patient developed DIC symptoms. The sirolimus therapy was discontinued and treatment with Kampo medicine (Eppikajyutsuto) was initiated, which is reported to have an anti-inflammatory effect and is effective against lymphatic malformations. Stabilization of the patient’s condition was achieved with no recurrence of pleural fluid within 18 months [12].

In one of the earliest reports, Dunkelman et al. (1989) presented the case of a 9-month-old boy with pleural lymphatic effusion, bone lesions, and hypoproteinemia. The boy was treated with drainage of the pleural cavity, followed by a thoracotomy with ligation of the thoracic and accessory thoracic ducts, as well as a pleurectomy. Pathological findings revealed numerous small endothelial-lined lymphatic vessels consistent with general lymphangioma. After 3 months, he experienced a recurrence, which was treated with decortication of the left lung and tetracycline pleurodesis. He remained asymptomatic during a 3-month follow-up [13].

A 14-year-old girl with chylothorax and cystic lesions was initially admitted due to cough, malaise, and fever. Radiological findings revealed right pleural effusion and multiple lesions in the bones and spleen. Thoracostomy and propranolol treatment were administered. However, she experienced a recurrence after 6 months with the same symptoms and right-sided pleural effusion. Subsequently, chemical and mechanical pleurodesis was performed via thoracoscopy as a palliative approach, but the outcomes of this treatment were not included in the study [14].

Riazuddin et al. recently presented the case of an 18-year-old female with pleural effusion on the right side causing collapse of the right lung, along with multiple lytic lesions of the ribs and clavicle. Initially she was treated with chest drainage, octreotide administration, and a low-lipid diet, however, there was no improvement. Subsequently, sirolimus therapy and total parenteral nutrition were initiated. During the course of treatment, she developed tachycardia and a thrombus in the left atrium was discovered, leading to the introduction of anticoagulation treatment. Following this, the decision was made to proceed with surgical intervention, where the fluid from the right pleural cavity was drained via thoracoscopy and the thoracic duct was clipped. Following this surgical procedure, the patient showed improvement in her condition [15].

The latest case report of a child suffering from pleural effusion in the course of GLA concerns a 6-year-old girl with a mediastinal mass causing bleeding into the left pleural cavity. Full symptomatic treatment was provided. She was managed with thoracoscopic mass removal and thoracic drainage, followed by sirolimus administration. Histopathological examination of the mass confirmed the diagnosis of lymphangioma. After her clinical condition improved, the patient was discharged home after 17 days and remains stable during follow-up. However, similar to our patient, a small amount of the fluid is still present in the pleural cavity [16].

In addition to soft tissue disturbances, another issue in GLA involves changes in bones. Severe lytic lesions of bones can result in pathological fractures, which may be the initial sign of the disease. Following an injury, an X-ray may reveal pathological morphology at the fracture site or multiple lesions adjacent to the fracture, prompting broader diagnostic examinations [10]. We can hypothesize that in our patient, the fracture of the thoracic vertebra was caused by undetected changes associated with lymphatic spread in the bones. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment can help prevent the progression of bone changes.

Rapamycin also appears to inhibit skeletal lytic lesions through its action. According to Ricci et al., 69% of patients with GLA showed improvement in bone changes, while 31% had stable bone disease involvement [17].

In conclusion, due to the rare occurrence and often life-threatening initial symptoms of GLA, we believe that the best way to treat this disease is through a multidirectional, intensive surgical and general approach. Moreover, we believe that prompt surgical intervention, such as closure of the thoracic duct, stabilizes the patient’s clinical condition and facilitates subsequent systemic treatment. After the initial symptomatic treatment, sirolimus now appears to be the optimal treatment option for controlling the disease. However, due to advancing knowledge about cellular processes, other causal treatments should also be explored.