Introduction

Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) encompasses a heterogeneous spectrum of vascular and non-vascular diseases. Despite growing evidence indicating unfavorable long-term outcomes, MINOCA remains an unrecognized and undertreated condition [1]. While patients with chronic angina pectoris without obstructive coronary arteries have a 0.2% risk of death, MINOCA increases this risk to 4.7% in 12 months follow-up [2]. Recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) occurs in 6.4% of MINOCA patients [3]. Some of these patients develop cardiogenic shock (CS), the most lethal form of MI, with mortality ranging from 40% to 50% [4].

Herein, we present the case of a woman initially presenting with MINOCA who subsequently developed ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) related CS after discharge.

Case report

A 51-year-old woman was admitted to hospital with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). Coronary angiography revealed a lesion in the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD), the hemodynamic significance of which was ruled out by fractional flow reserve assessment (Figure 1 A). The procedure was uncomplicated. At discharge, the patient was prescribed aspirin, ticagrelor, β-blocker, statin, and proton pump inhibitor.

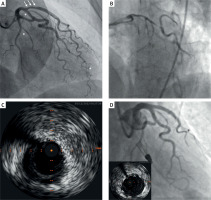

Figure 1

A – Initial angiography during myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) episode. In the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) there is a long 40% lesion (arrows), whose hemodynamic significance was ruled out in the fractional flow reserve (FFR) examination. Additionally, there are other lesions in coronary arteries of small vascular diameter (asterisks). B – Emergent angiogram performed during ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)-related cardiogenic shock a few days after discharge with a MINOCA diagnosis. The left main coronary artery (LMCA) and circumflex artery (Cx) are significantly diseased with distal parts of LAD and Cx occluded, with Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade 0. C – Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) revealed massive dissections of all branches of the left coronary artery classified as spontaneous coronary artery dissection type 2b. D – Final angiogram demonstrating good result of the procedure and the Impella CP implanted into the left ventricle. Bottom left corner – IVUS image showing good stent apposition

Four days later, the patient was emergently readmitted following two episodes of cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation in the setting of STEMI-related CS. The patient had arterial blood pressure of 91/60 mm Hg and a heart rate of 90 beats per minute. Her skin was warm, and no abnormalities were detected during lung and cardiac auscultation. Despite the absence of clinical signs of hypoperfusion and borderline normal blood pressure, we classified the patient as Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) stage C, considering the elevated lactate level of 6.5 mmol/l. Echocardiography showed reduced left ventricular ejection fraction of 30% with regional wall motion abnormalities but no evidence of scar formation. No left ventricular thrombus or aortic valve abnormalities were observed. Emergent coronary angiography revealed a massive lesion of the left main coronary artery (LMCA) extending into the LAD and circumflex artery (Cx) with Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade 0 (Figure 1 B). Intravascular ultrasound examination confirmed multivessel dissection (Figure 1 C). An Impella CP (Abiomed Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) was implanted via the femoral artery under ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance. The lesions were prepared with a Wolverine 2.5 mm cutting balloon (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) to decompress the intramural hematoma and restore peripheral coronary flow. Subsequently, a Xience Pro S 3.5 × 38 mm drug-eluting stent was implanted in the LMCA/LAD at 18 atm with proximal optimization technique (POT) using a 5.5 × 15 mm non-compliant balloon. Kissing balloon technique was performed with a 4.0 × 15 mm non-compliant balloon in the LMCA/LAD and a 3.5 × 12 non-compliant balloon in the LMCA/Cx. Finally, re-POT was performed with the 5.5 × 15 mm non-compliant balloon at 20 atm (Figure 1 D). Due to oozing around the repositioning sheath, the Impella CP was removed, and catecholamines were initiated. The patient was transferred to the Intensive Cardiac Care Unit for further treatment. No arrhythmia recurrence was observed during remainder of her hospitalization. Follow-up echocardiography showed improved left ventricular ejection fraction of 50%. The patient was discharged home on the 9th day of hospitalization in good physical condition without neurological impairment.

Discussion

This case is interesting due to its complexity on multiple levels. First, although fractional flow reserve was conducted during the initial procedure to rule out hemodynamically significant disease, further investigation might have been warranted [5].

Intracoronary optical coherence tomography (OCT) and, to a lesser extent, intravascular ultrasound can provide valuable information that impacts diagnosis and treatment. Intracoronary imaging (ICI) allows differentiation of plaque-induced events (plaque rupture, erosion, ulceration, calcific nodule), thromboembolism, intramural hematoma, spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) or vasospasm in a vessel without obstructive atherosclerosis. Given the high prevalence of coronary causes in MINOCA, it is recommended to perform ICI routinely in the absence of an obvious extracardiac or non-coronary cardiac cause of MINOCA. Technically, ICI should be done in the vessel corresponding to the ischemic territory identified in echocardiography or electrocardiogram, or to the vessel with coronary lesions [6]. Unfortunately, despite proven clinical benefits, ICI remains underutilized worldwide [7–9], often due to high cost, procedure prolongation, and lack of reimbursement [10]. However, in the present case, even if intramural hematoma in the proximal LAD had been revealed by intracoronary visualization, conservative therapy would have remained the first-choice treatment given the absence of high-risk anatomy and the patient’s hemodynamic stability. Apart from intracoronary imaging, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) should be performed in patients without definitive diagnosis after the ICI test, as it enables assessment of the structure of the myocardium or confirmation of the presence of intraventricular thrombus predisposing to a thromboembolic event. The most typical findings in CMR scanning in patients with MINOCA include ischemia, myocarditis, takotsubo syndrome and cardiomyopathy. In a cohort of 125 consecutive patients with troponin-positive chest pain without obstructed coronary arteries, CMR identified the cause in 87% of cases [11]. Based on observational data, multimodal imaging including CMR and OCT allows for a definite diagnosis in 84.5% of consecutive women with MINOCA [12]. Moreover, in patients with electrocardiographic changes consistent with regional wall motion abnormalities, the combination of CMR and OCT identifies the underlying cause of MINOCA or confirms the diagnosis of myocardial infarction in 100% of patients [13]. Unfortunately, despite increasing availability, access to CMR remains limited in some regions [14, 15].

The etiology of STEMI in this patient remains unclear. While angiography suggested de novo SCAD, the recent MINOCA hospitalization raises the possibility of either iatrogenic coronary dissection or continuation of previously unrecognized SCAD. Although CS is uncommon in SCAD, SCAD-STEMI is more frequently complicated by CS than atherosclerotic STEMI [16]. A specific approach to CS in such settings has not been established. However, CS management should follow a prespecified team-based approach to improve survival. For SCAD, guideline-directed medical therapy remains the treatment of choice in most cases, but percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) may be necessary in cases of circulatory collapse, persistent angina, or LMCA involvement [17]. However, PCI for SCAD carries a higher risk of failure and severe complications compared to PCI of atherosclerotic lesions, including dissection propagation or acute vessel closure [18]. Particularly unfavorable outcomes are reported in PCI of spontaneously dissected LMCA [19]. Despite reports of successful initial conservative treatment, PCI of dissected LMCA should be considered even in transiently stable patients [20–22]. In our case, a cutting balloon was used to tear the intimal flap and decompress the intramural hematoma, allowing safe stent implantation in the LMCA/LAD without hematoma propagation. This technique has been previously described [22, 23].

Finally, this case exemplifies the early use of percutaneous left ventricular assist device (pLVAD) support in myocardial infarction-related CS. In recent decades, two therapies tested in randomized controlled trials have improved outcomes in CS: early revascularization, proven effective in the SHOCK trial [24], and microaxial flow pump support, associated with favorable outcomes in the DANGER SHOCK study [25]. In the latter, patients received mechanical circulatory support in SCAI stages C, D, and E. In our case, although the patient did not exhibit clinical signs of peripheral hypoperfusion or marked hypotension, the elevated lactate level prompted us to classify her as SCAI stage B/C. Given the extremely high-risk coronary anatomy and clinical setting, we assessed the probability of clinical deterioration as very high. Consequently, we opted for early pLVAD use to unload the left ventricle, support the heart during high-risk PCI, and prevent irreversible end-organ damage. Fortunately, the patient did not have peripheral arterial disease, which might have precluded mechanical circulatory support. Despite women being at higher risk for vascular complications, we observed no major complications in this case. Obtaining large-bore access under fluoroscopic and ultrasound guidance reduces the risk of arterial damage and is recommended even in acute settings.

Conclusions

We presented a young woman who developed STEMI-related CS days after presenting with MINOCA. Despite being in the early stage of cardiogenic shock, pLVAD was successfully used to maintain hemodynamic stability during complex PCI and prevent clinical deterioration. However, the early application of mechanical circulatory support in CS requires further investigation.