Introduction

In 2018, head and neck cancer (HNC) ranked as the seventh most prevalent cancer globally, with 890,000 newly diagnosed cases and 450,000 deaths [1]. Projections indicate a 30% annual increase in HNC cases by 2030 across both developed and developing countries [2]. Head and neck cancers are predominantly squamous cell carcinomas, a group of epithelial malignancies affecting the upper respiratory and digestive tracts; these include the lips, oral cavity, oropharynx, nasal cavity, nasopharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx/upper trachea [1, 3]. Historically, HNC was most common among older individuals with a history of heavy tobacco and alcohol use. However, this pattern has shifted in the Western world due to declining tobacco use [4]. The rising incidence of oropharyngeal cancer in the USA and Europe is now largely attributed to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection [2].

Stage I or II disease can often be cured with surgery or definitive radiotherapy alone; however, these stages are diagnosed in only 30–40% of patients [1]. In contrast, stage III or IV disease, which accounts for over 60% of HNC cases, is associated with a high risk of local recurrence (up to 40%) and distant metastasis. As a result, the prognosis remains poor, with a 5-year overall survival rate below 50% [1]. Over the past two decades, immunotherapy has emerged as a groundbreaking approach to cancer treatment, underscoring the pivotal role of the immune system in regulating cancer cells. Specifically, T-cells and antigen-presenting cells form the cornerstone of the immune response to cancer [4]. In 2016, nivolumab, an anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1) antibody, was approved after demonstrating lasting responses and improved survival in patients with recurrent or metastatic HNC treated with platinum-based therapies [1, 5]. The programmed death 1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is crucial in the tumor microenvironment (TME), where it regulates the induction and maintenance of immune tolerance. Programmed death- ligand 1 and PD-L2 are ligands of PD-1, and their interaction influences T-cell activation, proliferation, and cytotoxic secretion, ultimately weakening anti- tumor immune responses in cancer [6]. However, resistance to nivolumab, particularly in HNC cases, presents a growing challenge, with response rates as low as 20% [7]. This review explores the mechanisms underlying nivolumab resistance and discusses strategies to address these challenges.

Material and methods

Search strategy

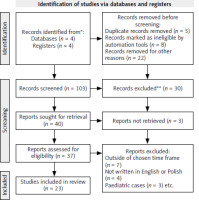

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, focusing on the mechanisms of nivolumab resistance in HNC. A comprehensive search of databases, including PubMed (Medline), Scopus (Elsevier), Embase (Elsevier), and Web of Science, was performed for articles published between 2016 and 2024.

Searching and data screening

The databases were meticulously searched by one author using specific key words, including “nivolumab resistance,” OR “mechanisms of nivolumab resistance,” OR “anti-PD-1 resistance,” OR “immunotherapy resistance,” AND “head and neck cancer,” OR “head and neck tumor,” OR “head and neck squamous cell carcinoma” (HNSCC), AND “HPV positive HNSCC,” AND “HPV negative HNSCC.” From the initial 103 articles identified, 23 met the eligibility criteria and were cited in this review. The PRISMA flowchart detailing the screening process is presented in Figure 1.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria for this systematic review were carefully defined, focusing on articles published within the timeframe of 2016–2024. Only papers written in English or Polish were considered for inclusion. Additionally, studies addressing pediatric cases were excluded from the review.

Data extraction and processing

Data from selected studies were manually extracted and systematically organized. Key information recorded included the authors’ names, publication dates, DOI numbers, types of HNC addressed, reasons for nivolumab administration, and mechanisms of resistance as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Data extraction from articles used in review

[i] ESCC – esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, HNSCC – head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, JAK-STAT – the Janus kinase (JAK) signal transducer and activator of transcription, N/A – not applicable, PI3K-γ – phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinnase gamma, Treg/Th17 – regulatory T-cells/T helper 17 celles, WNT/β – canonical Wnt pathway

Results

Database search results

A manual search of the specified databases yielded 103 results. After screening the titles and abstracts, articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded, resulting in a final selection of 23 articles.

Bias tool assessment

The reporting bias table was created using criteria adapted from ROBIS and the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. Each study was assessed for selective reporting, outcome reporting transparency, and publication bias evidence. Risk levels (low, unclear, or high) were assigned based on the available evidence, ensuring a systematic and objective evaluation of reporting bias as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Table reporting bias of articles used in the review

Discussion

Intrinsic mechanisms of a tumor

For immune cells to recognize and target tumor cells, antigens must be presented on the tumor cell surface by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, specifically human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecules. Tumor cells can evade immune detection through downregulation of HLA class I expression. Without effective antigen presentation, cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) cannot recognize and eliminate tumor cells. Mutations in the β-2-microglobulin (B2M) gene can result in the loss of HLA class I expression on the surface of tumor cells, preventing immune detection and reducing the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors [8, 9]. Furthermore, mutations in the antigen-processing machinery can lead to defects in proteins essential for peptide loading onto MHC molecules, such as the transporter associated with antigen processing, thereby impairing antigen presentation [10].

Another mechanism tumors use to downregulate antigen expression involves interferon (IFN) signaling pathway mutations. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) is critical for the immune system to target tumors, as it activates tumor antigen presentation and boosts CTL activity [9]. Mutations in the JAK1 and JAK2 genes, which encode kinases in the the Janus kinase signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) signaling pathway activated by IFN-γ, are a primary cause of antigen suppression. Mutations in these genes can prevent the IFN-γ signal from reaching the tumor cell, thereby reducing antigen presentation and immune cell recruitment, leading to resistance [9–11]. Additionally, IFN-γ typically enhances the ability of CTLs to kill tumor cells. With disrupted JAK-STAT signaling, this function is impaired, allowing the tumor to survive despite immune system attacks [10].

MYC is a proto-oncogene, located at 8q24, often acquired through mutations that plays a crucial role in regulating various cellular processes [12]. MYC has been shown to regulate PD-L1 expression, which plays a key role in helping tumor cells evade the immune system [13, 14]. MYC amplification was shown to significantly alter the tumor transcriptome, causing specific pathways to be upregulated. One of these critical pathways is the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, the activation of WNT/β-catenin signaling creates an immunosuppressive environment by reducing the recruitment and activity of immune cells such as T-cells, dendritic cells and cytotoxic T-cells, essential for an effective immune response [9, 15]. This pathway is also central to the upregulation of the glycolytic pathway, to meet the tumor’s increased energy demands, and enhancement of fatty acid synthesis, providing lipids necessary for building cellular membranes and storing energy [15].

Tumor immunosuppressive environment

The tumor microenvironment plays a critical role in resistance to immunotherapy. The tumor microenvironment consists of tumor cells, immune cells, blood vessels, signaling molecules, and extracellular matrix components [16]. Specific pathways in tumor cells can create an immunosuppressive environment. An example of this is PTEN, which normally suppresses the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT/mTOR pathway and contributes to an immunosuppressive TME when activated. PTEN loss is associated with decreased T-cell infiltration and inhibition of autophagy, a critical process for T-cell-mediated tumor cell death [17]. Tumors with PTEN loss show resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors such as nivolumab because they fail to elicit an adequate immune response [9, 10].

Different types of cells also play a significant role in the TME and contribute to resistance. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in the TME promote an immunosuppressive environment by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-β [9]. They also contribute to the upregulation of PD-L1 by secreting vascular endothelial growth factor, which, along with low oxygen levels and new blood vessel formation in the tumor microenvironment, impairs CTL proliferation and function [10].

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are another critical component of the TME that inhibits immune responses [18]. They suppress T-cell function and promote tumor growth by releasing immunosuppressive molecules such as arginase, prostaglandin E2, and reactive oxygen species [9, 19, 20]. They also produce indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, an enzyme that depletes tryptophan in the tumor microenvironment. This limits CTL function and promotes regulatory T-cell (Treg) recruitment, contributing to immune evasion [10].

Tumor-associated myeloid cells also exhibit an M2-like phenotype that is immunosuppressive in the TME. They release factors such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, which promotes the recruitment and activation of additional myeloid suppressor cells, creating a cycle of immune evasion [20, 21]. In tumors resistant to PD-L1 blockade, the myeloid cells suppress CD8+ T-cell proliferation and activation, limiting the immune system’s ability to recognize and destroy tumor cells, despite PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. The γ isoform of phosphoinositide 3-kinase, highly expressed in myeloid cells, is a vital mediator of this immune suppression [21].

Immune checkpoints and pathways

Cancer cells can manipulate immune checkpoints – molecules that typically function as regulatory mechanisms to prevent the immune system from targeting healthy tissue. In the context of cancer, these regulatory pathways are exploited to evade immune detection and destruction.

One important checkpoint molecule is PD-L1, which is frequently overexpressed on tumor cells. Programmed death-ligand 1 interacts with the PD-1 receptor on T-cells, inhibiting their activation and preventing an immune response against the tumor. Even in the presence of anti-PD-1 therapy, sustained expression of PD-L1 can contribute to ongoing immune suppression [10].

Another critical immune checkpoint involves T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3 (TIM-3), expressed on exhausted T-cells. Upon binding to its ligand, galectin-9, TIM-3 induces apoptosis in T helper type 1 (Th1) cells and impairs CTL function. The exhausted T-cells show decreased production of essential cytokines, such as interferon-γ, crucial for an anti-tumor immune response.

Lymphocyte activation gene-3 is another inhibitory receptor found on T-cells, natural killer cells, and tumor- infiltrating lymphocytes, particularly CD8+ T-cells, in various cancer types, including oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) [22]. In the TME, persistent antigen exposure causes chronic activation of these immune cells, maintaining LAG-3 expression. LAG-3 interacts with MHC II molecules, reducing T-cell activation and function [22]. This state of T-cell exhaustion is characterized by impaired T-cell proliferation and cytokine production, making it difficult for the immune system to mount an effective anti-tumor response. Since nivolumab blocks PD-1 to rejuvenate T-cell activity, this exhaustion induced by LAG-3 severely limits its effectiveness. LAG-3 is also involved in Treg suppression, promoting an immunosuppressive environment [9, 10].

Co-expression of inhibitory immune checkpoints (LAG-3, TIM-3, VISTA, and PD-1) is frequently observed in OPSCC, particularly in HPV-related cases. This co-expression acts synergistically to suppress immune responses more robustly than any one checkpoint alone, creating a deeper state of T-cell exhaustion [10].

Potential markers

Immunotherapy has emerged as a promising treatment option for HNSCC, particularly through the use of anti-PD-1 agents such as nivolumab. However, not all patients respond equally to these therapies, and identifying biomarkers that predict resistance or sensitivity is crucial for improving outcomes. Recent research has uncovered several genetic, epigenetic, and immune-related factors that play a significant role in determining how HNSCC patients respond to immunotherapy, providing potential avenues for more personalized and effective treatment approaches.

One notable finding is the association between elevated c-Myc mRNA expression and resistance to treatment in HPV-negative HNSCC tissues. This overexpression correlates with TP53 mutation status and is supported by evidence showing that c-Myc exhibits hypomethylation in HNSCC tissues compared to normal tissues. Elevated c-Myc levels have been linked to reduced immune infiltration and a weakened immune response, making it a poor prognostic indicator. Interestingly, c-Myc overexpression also appears to suppress the expression of immune checkpoints, a critical mechanism of immune evasion [19]. These findings suggest that c-Myc amplification could serve as a predictive biomarker for resistance to nivolumab. By identifying patients with elevated c-Myc expression, clinicians may be better equipped to personalize treatment plans and explore alternative therapeutic strategies [15].

In parallel, another biomarker worth considering is the pretreatment peripheral blood regulatory T-cells/T helper 17 celles cell ratio. Studies have suggested that a higher ratio could predict innate resistance to anti-PD-1 therapies and a decrease in survival following neoadjuvant therapy [23]. Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in tumors is another crucial biomarker for predicting the response to anti-PD-1 therapies such as nivolumab. Tumors with high PD-L1 expression typically respond more favorably to nivolumab, as the drug inhibits the interaction between PD-1 on T-cells and PD-L1 on tumor cells, thereby restoring T-cell activity [9].

Additionally, one study found five distinct cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) subtypes in HNSCC. Two of these subtypes, HNCAF-0 and HNCAF-3, are predictive of positive responses to PD-1 checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. These subtypes stimulate CD8 T-cell activity, promoting a cytotoxic immune response, while HNCAF-1 is linked to immunosuppression and T-cell exhaustion. Notably, HNCAF-0/3 fibroblasts were shown to induce a tissue- resident memory phenotype in CD8 T-cells, marked by the inhibitory receptor NKG2A, which is a target for emerging immunotherapies [7].

Genetic and immune factors, such as elevated c-Myc expression, PD-L1 levels, and specific CAF subtypes, play crucial roles in predicting responses to immunotherapy in HNSCC. These biomarkers provide valuable insights into resistance mechanisms, paving the way to more personalized treatment approaches. By integrating molecular and immune profiling, clinicians can optimize the effectiveness of immunotherapy and improve patient outcomes.

Conclusions

Head and neck cancer remains a significant global health concern, with a rising incidence rate and a growing recognition of resistance to immunotherapies such as nivolumab. While anti-PD-1 antibodies such as nivolumab have marked a milestone in the treatment of HNC, especially for recurrent or metastatic cases, resistance to these therapies poses a substantial challenge. The mechanisms underlying nivolumab resistance are multifaceted, involving intrinsic tumor properties, the immunosuppressive TME, and dysregulation of immune checkpoints.

Intrinsic tumor mechanisms include downregulation of antigen presentation through mutations in HLA class I molecules, B2M, and alterations in the IFN-γ signaling pathway. Amplification of MYC, a proto-oncogene, further contributes to immune evasion by altering the TME and promoting pathways such as WNT/β-catenin signaling. The tumor microenvironment also plays a crucial role in resistance, characterized by the presence of immunosuppressive cells including TAMs, MDSCs, and regulatory T-cells that inhibit cytotoxic TLC function. Additionally, tumor cells exploit immune checkpoints such as PD-L1, TIM-3, and LAG-3 to avoid immune surveillance.

These findings underscore the complexity of nivolumab resistance in HNC and the necessity for a multi-targeted approach to overcome it. Identifying such predictive biomarkers as MYC amplification and PD-L1 expression could facilitate the development of personalized treatment strategies and improve patient outcomes. Future research should focus on understanding the intricate interactions within the TME and developing combination therapies that target multiple resistance pathways.