Acute pulmonary embolism (PE) is a life-threatening disease. Thrombolysis is the treatment of choice for hemodynamically unstable patients. However, surgical embolectomy or catheter-directed therapy may be considered in patients with contraindications to or failure of thrombolysis. These strategies are increasingly used in selected hemodynamically stable patients with intermediate- to high-risk PE, though clinical experience remains limited. In this context, hybrid therapy combining catheter-based and surgical treatment may improve the clinical status and prevent chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). We present a case illustrating this evolving approach [1, 2].

A 40-year-old woman with a history of left breast cancer treated with surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy in 2021, on chronic antiestrogen therapy and with no prior history of venous thromboembolism, was hospitalized for intermediate- to high-risk PE. She reported sudden dyspnea and fatigue in the days before admission. On examination, she had respiratory distress, sinus tachycardia (110 bpm), and oxygen saturation of 90% with minimal effort. Blood pressure was normal. Electrocardiography (ECG) showed an S1Q3T3 pattern. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed right ventricular (RV) overload, RV dilation, reduced TAPSE (13 mm), McConnell’s sign, and tricuspid regurgitation (Vmax 3.7 m/s). There were no echocardiographic signs of chronic pulmonary hypertension (i.e. RV wall thickening, non-collapsing vena cava). Computed tomography confirmed a massive thrombus occluding the right pulmonary artery (Figure 1). Compression ultrasound revealed left popliteal vein thrombosis. Troponin (0.014 ng/ml), NT-proBNP (331 pg/ml), and D-dimer (1161 ng/ml) levels were elevated. The sPESI score was 3.

Due to failure of initial anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin (UFH) and contraindications to thrombolysis (high bleeding risk), the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) opted for an invasive approach. Pulmonary angiography showed a large thrombus with slow perfusion to the upper lobe and no flow to the middle and lower lobes (Figure 2). Multiple catheter-based embolectomy attempts with the Penumbra 8F device achieved only minimal improvement. A low-dose local alteplase infusion was administered.

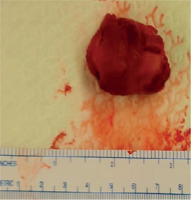

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) performed 2 days later excluded neoplastic infiltration of the pulmonary artery and confirmed a persistent thrombus in its proximal part (Figure 3). Despite 5 days of intensive UFH infusion, no clinical or angiographic improvement was observed. The patient was transferred for surgical pulmonary embolectomy, during which the thrombus was removed from the right pulmonary artery (Figure 4). After 3 weeks of UFH/low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), rivaroxaban was introduced. Follow-up TTE showed no RV overload. The patient improved and began rehabilitation after prior oncological treatment.

Figure 3

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging excluding neoplastic infiltration of the pulmonary artery

This case raises important considerations in PE management, including malignancy, prolonged symptoms, and massive clot burden with stable hemodynamics. Symptom duration should guide treatment, as prolonged PE may reflect chronic thromboembolic disease (CTED) or CTEPH, limiting the efficacy of catheter-based therapy. Organized thrombi may also suggest angiosarcoma, metastases, or coexisting acute PE and CTEPH. The duration of symptoms, the presence of a large, well-organized thrombus, and the lack of response to adequate anticoagulation all suggest an acute-on-chronic PE. Large thrombi persisting for over 10 days are very difficult to remove, and surgical referral should be considered based on operator experience [3, 4].