Nowadays, clavicle fractures are treated with titanium plates and screws as an optimal method of stable fixation, making early rehabilitation of patients possible. Martin Kirschner introduced intramedullary osteosynthesis using wires (later named Kirschner’s wire or K-wire) in the year 1909. Migration of wires is a well-known complication, with the rate of 5.8–54% [1]. Since 1943, for medicolegal reasons, this complication has probably been under-documented.

A 35-year-old male patient presented to us with symptoms of pain and numbness in the left arm for a period of 1 year. Initially, it was a mild, periodic pain, but it had become more frequent and severe – around 5 out of 10 on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). He had a previous history of right clavicle surgery with Kirschner’s wire fixation 6 years ago.

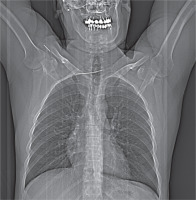

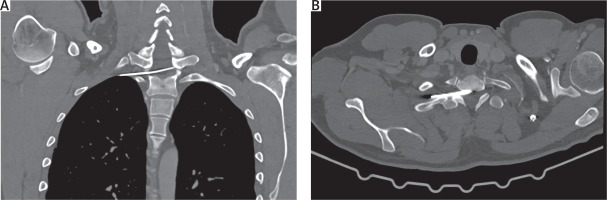

On radiological evaluation on chest X-ray a broken K-wire was observed with the distal part in the clavicle and the proximal part migrated into the thorax (Figure 1). Computed tomography revealed that part of the broken wire lay transversely across the spinal canal at the level of Th1. The length of this part was 7.0 cm, with the tip in the right mediastinum, posterior to the superior vena cava (Figures 2 A, B).

Subsequently, right non-intubated video-assisted thoracic surgery (NIVATS) was performed. The patient was positioned on the back with the right arm abducted. Anesthesia was administered with propofol, fentanyl, and dexmedetomidine. Intravenous dexmedetomidine infusion at a dose of 1 μg/kg for 20 minutes was started before surgical incision with further infusion 0.7 μg/kg/h. Surgical incision sites were anesthetized with 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine hydrochloride, and propofol 2 mg/kg and fentanyl 2 μg/kg were started before surgery with intraoperative infusion at 3.8 mg/kg/h and 2.6 μg/kg/h, respectively. The target bispectral index value was 40–50 during surgery.

A uniportal approach was performed in the third intercostal space in the middle axillary line 3.0 cm in length. The pleural space was inspected, and no adhesions were observed. A mediastinotomy was performed with LigaSure (Covidien). The tip of the broken K-wire was identified and removed with forceps in the straight direction of the wire in the spinal canal. No bleeding or cerebrospinal fluid leakage was observed. An 18 Fr chest drain was placed in the chest cavity, and the wound was closed in layers. The next operation was performed through the supraclavicular (from the previous surgery) incision, and the broken part of the K-wire was removed from the clavicle by orthopedic surgeons. The patient was fully awake on the table after surgery and was transferred to the ward. On the next day, the chest drain was removed and the patient went home. All neurological symptoms completely disappeared on the third day after surgery. The follow-up period was 3 years, without any symptoms.

Migration of K-wires into the spinal canal was first reported in 1977 [2]. Usually, patients with wire migration to the spinal canal have no spinal cord injury and no neurological symptoms [3]. The timeframe between surgery and diagnosis of wire migration was from 1 day to 19 years [4]. Routine radiographic follow-up established the diagnosis of wire migration, which is observed in most cases between the second and fourth month [5]. In the literature, almost 20 cases of wire migration into the spinal canal were described [4]. The clinical picture varies from asymptomatic to different degree of paresis, including Brown-Sequard syndrome. After removal of migrated wires from the spinal canal, the recovery was complete in most cases, and hypesthesia of the lower limbs or permanent sexual dysfunction occurred in some cases. Migrated wires should be removed mandatorily, regardless of presence or absence of any clinical signs. Only 2 cases of VATS removal of migrated wires have been published – in 2013 and 2018 [6, 7]. By 2016, nearly 2500 NIVATS cases of different degrees of difficulty, surgical risks, and operated pathology had already been published. However, no case of NIVATS removal of migrated wires from the spinal canal had been reported in the literature.

In conclusion, we suggest that the combination of a novel method of anesthesia (non-intubated) and minimally invasive uniportal approach, whenever the anatomy and physiology of the patient allows, could be a feasible and safe tool for removal of migrated wires into the thoracic cavity in meticulously selected patients and may become a part of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) concept in this category of patients.