Occlusion MI: a revolution in acute coronary syndrome

The 2025 ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes claims that “Patients with NSTEMI may have a partially occluded coronary artery leading to subendocardial ischemia, while those with STEMI typically have a completely occluded vessel leading to transmural myocardial ischemia and infarction.” [1]. This is accompanied by a visual representation of a partially occlusive thrombus labeled ‘NSTEMI’ above an electrocardiogram (ECG) showing ST depression and T wave inversion, and a completely occlusive thrombus labeled ‘STEMI’ above an ECG showing ST elevation. This paradigm has remained despite two decades of angiographic and evidence-based ECG advances, which highlight the multiple reasons why a revolution in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is needed, and has begun.

Origin: STEMI trials never differentiated between occlusive and non-occlusive MI

Prior to the use of thrombolytics, treatment for myocardial infarction (MI) was essentially limited to hospitalization in coronary care units where patients could be treated for pain, monitored on continuous ECG and defibrillated if necessary. The primary goal of MI classification in that era was prognostication: after completion of the acute event, MIs were classified retrospectively as either Q wave or non-Q wave. When thrombolysis emerged as a disease-modifying treatment option, the paradigm shifted in an effort to prospectively identify patients most likely to benefit from intervention. The shift from Q-wave/non-Q-wave to STEMI/non-STEMI was not just a change in name, but a revolution in the way patients with MI were identified, treated, classified, and studied, which reshaped the world of emergency cardiology including prehospital, emergency departments, and cath labs.

Today, STEMI criteria are widely believed to faithfully identify patients with acute coronary occlusion (ACO), as illustrated by the 2025 ACC Guidelines. However, the 1994 Fibrinolytic Therapy Trialists’ meta-analysis that gave rise to STEMI criteria never differentiated patients between occlusive and non-occlusive MI [2]. It did find that those with unspecified “ST elevation” benefited from thrombolytics. But among the 9 trials included in the meta-analysis, none used current STEMI criteria to enroll patients, 4 had no ECG requirements of any kind, and there were no angiographic data.

Outcomes: STEMI criteria have high rates of false positive and missed occlusions

The 2025 ACC Guidelines implicitly acknowledge the clinical importance of vessel patency, but falsely dichotomizes these groups into STEMI and NSTEMI. The guidelines cite the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction, which also provides no underlying evidence for STEMI criteria [3].

Since the paradigm first emerged, widespread angiographic data have emerged showing the outcomes of STEMI criteria: While the paradigm has led to clear benefits for true positive STEMI, there are high rates of false positives leading to unnecessary cath lab activation [4]. Worse, many patients with acute occlusion do not have ECGs that manifest diagnostic ST elevation. Khan et al. performed a meta-analysis of 40,777 patients with NSTEMI and found that 25.5% had total occlusion of the culprit artery, a finding associated with a 67% increase in mortality as compared to patients without total occlusion [5]. Hung et al. performed another meta-analysis and found that 34% of 60,898 patients with NSTEMI had thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) grade 0–1 flow at next day angiography. Both studies found that those NSTEMI with occlusion had worse outcomes than those without occlusion, in spite of younger age and fewer comorbidities [6].

Defenders of the STEMI paradigm argue that patients with ACO without STEMI are triaged appropriately in the current paradigm, since it is assumed that they present with high-risk features such as medically refractory chest pain or hemodynamic or electrical instability. However, there are two flaws with this reasoning. First, Khan’s meta-analysis found no difference in the rate of high-risk clinical features among NSTEMI patients with and without total occlusion. Second, a recent study of real-world NSTEMI patients found that even when very high risk features are present, they rarely trigger immediate angiography as recommended [7].

Anticipating a future paradigm shift, Khan et al. wrote in their 2017 study that “Better risk stratification tools are needed to identify such high-risk acute coronary syndrome patients to facilitate earlier revascularization and potentially to improve outcomes”. But to do this would require a classification system that highlights missed occlusions.

Research and quality improvement: STEMI criteria miss occlusions retrospectively

Despite poor sensitivity for ACO, this critical diagnostic shortcoming is concealed by the STEMI paradigm’s inherent “no false negative paradox” [8]. Patients with STEMI on ECG are either true positive (if ACO is present) or false positive (if ACO is absent). Patients without STEMI on ECG and without ACO are true negative. However, the well-documented group of patients without STEMI on ECG but with ACO are not recognized as false negatives; instead they are simply another ‘NSTEMI.’

As a result, discharge diagnoses change to highlight false positive STEMI but not false negative STEMI [9]. This creates a bias in the literature and undermines quality improvement efforts. De Alencar et al. found only three studies evaluating the performance of STEMI criteria to identify ACO. The very low pooled sensitivity of 43.6% shows how far the 2025 guideline graphic deviates from reality [10]. STEMI quality improvement serves true positive STEMI patients, and ignores false negative STEMI patients. This includes patients with subtle occlusions who get “code STEMI” activation and a discharge diagnosis of “STEMI” despite never meeting STEMI criteria, which reinforces the STEMI/NSTEMI false dichotomy.

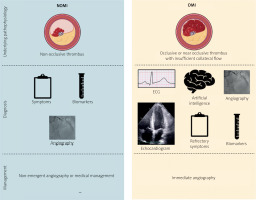

Shift: A new paradigm is available

In their 2018 publication the OMI Manifesto, Smith and Meyers introduced a new paradigm of MI [11]. It is an understanding of MI based on the disease’s underlying pathophysiology, rather than a single feature (ST elevation) of a single surrogate test (ECG). Occlusion myocardial infarction (OMI) represents acute coronary occlusion (ACO) or near occlusion with insufficient collateral circulation to prevent irreversible infarction in at-risk myocardium. Non-OMI represents MI due to non-occlusive events (Figure 1).

OMI research can be challenging due to the lack of a gold standard diagnostic test. Although coronary angiography may initially seem suited to the task, up to 20% of true STEMIs have TIMI flow grade 3 at the time of angiography due to spontaneous or medication-assisted recanalization. For this reason, research definitions of OMI include not only culprit vessels with reduced TIMI flow grade, but also acute culprit lesions with normal TIMI flow grade and with very high peak troponin.

Following up on this, Meyers et al. studied 808 patients with acute MI and found similar mortality and infarct size among patients with OMI both with and without STEMI criteria. More importantly, the study demonstrated proof of concept for advanced ECG interpretation. Meyers and Smith blindly interpreted ECGs for the diagnosis of OMI with 94% agreement. Moreover, they more than doubled sensitivity for ACO with preserved specificity [12]. Separately, Aslanger et al. studied 3000 patients with and without MI and performed blinded ECG interpretation for OMI. They reported high interobserver agreement and found that classification on the basis of OMI or non-OMI was more predictive of mortality than classification on the basis of STEMI [13].

Citing Meyers, the ACC published “Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Evaluation and Disposition of Acute Chest Pain in the Emergency Department”. It warns that STEMI criteria “miss a significant minority of patients with acute coronary occlusion” and advises that “the ECG should be closely examined for subtle changes that may represent initial ECG signs of vessel occlusion” [14]. This contradicts the outdated visual from the 2025 ACC Guidelines, and calls for a shift in focus from one simplistic ECG sign to a multi-pronged clinical focus on patients with OMI.

The future is now: Join today

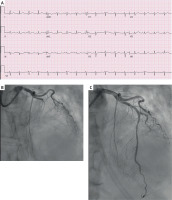

There is accumulating evidence for a range of ECG findings that are diagnostic for OMI, including ischemic anterior ST depression from posterior OMI, Smith-modified Sgarbossa criteria in left bundle branch block or paced rhythm, hyperacute T waves including De Winter sign, and primary ST depression in aVL reciprocal to subtle inferior OMI (Figure 2). Although these and other findings can improve our ability to detect OMI, clinical implementation is limited by perceived complexity. Fortunately, artificial intelligence is well suited to this task, and multiple independently developed models have demonstrated dramatic improvements in sensitivity [15].

Figure 2

A – ECG negative for STEMI, but diagnostic for OMI with hyperacute T waves in I, aVL, V5, and V6 and reciprocal changes in inferior leads. B – Coronary angiography showing TIMI 0 mid left anterior descending artery. C – The same patient after percutaneous coronary intervention

The OMI revolution is taking place right now, with an increasingly robust body of literature in support [16]. Clinicians wishing to join the revolution can begin today. Central to the OMI paradigm is the notion that ECG does not define the disease; complementary tools such as bedside echocardiography, advanced imaging, and fastidious attention to signs of refractory ischemia assist the clinician in appropriate triage. Larger systemic changes are also required, such as reforming existing quality improvement efforts like the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. As with the shift from Q-wave to STEMI, the OMI paradigm shift is far more than a name change: It is a transformation in the way that patients are identified, treated, classified, and studied, which can reshape emergency cardiology again.

The widespread availability of primary percutaneous coronary intervention has transformed MI from a disease with a case fatality rate exceeding 30% into an imminently survivable event. We must now focus our efforts on identifying patients most likely to benefit.