Introduction

In clinical practice, pacemaker-induced tricuspid valve regurgitation (TR) presents a challenge. Implantation of permanent pacemaker leads in the endocardium of the right ventricle (RV) frequently leads to regurgitation of the tricuspid valve (TR). If the pacemaker lead adheres to the TV leaflet and/or the sub-valvular equipment, or if there is deformation of the leaflet, restoring the TV can be challenging and may require a tricuspid valve replacement (TVR).

According to reports, between 4% and 13% of individuals who undergo TVR also have a transvenous pacer system [1]. In this clinical challenge, there are a few options available. First, implanting an epicardial pacemaker has the advantage of almost eliminating the risk of endocarditis and injury to the inner cardiac structures, and the same device longevity. Epicardial pacing is commonly used in patients with congenital heart disease, with the significant disadvantage of requiring at least a partial sternotomy to implant or update the pacing leads [2]. The second option is to insert a pacemaker lead into the coronary sinus. Third, subcutaneous ICD is the only alternative treatment option for people who require simply defibrillation rather than cardiac pacing. Finally, in 2004, Aris et al. [3] presented a procedure that involved placing the original pacemaker lead outside the ring of the new TV prosthesis in a paravalvular position. Several studies have shown that this technique ensures the preservation of the previously implanted transvenous pacemaker lead [4–8].

Aim

Our aim in this current report is to describe our unit’s mid-term results with the lead-sparing technique in TVR with an emphasis on lead data in the follow-up.

Material and methods

Cohort

Between 2014 and 2024, a total of 15 patients who had previously had a transvenous pacemaker system underwent TVR. Consent was obtained from the participants after providing them with all the necessary information, and the study was approved by the institutional review board. We gathered demographic data, disease characteristics, preoperative echocardiographic and/or electrophysiologic variables, operational data, and postoperative parameters (such as time to extubation and length of stay in the critical care and hospital) from patients retrospectively. Follow-up was conducted for all patients. During follow-up, echocardiographic parameters and electrophysiological data were determined. Transthoracic echocardiography was utilized to evaluate ventricular and valvular function by measuring certain variables as outlined by the American Society of Echocardiography [9, 10]. The electrophysiology team recorded lead data, which included pace and sensing characteristics.

Surgical technique

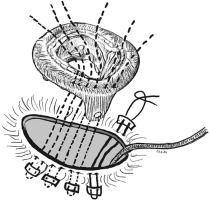

After median sternotomy, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is instituted with aortic and bi-caval cannulation. The decision to perform the procedure under a beating heart versus an arrested heart was made based on anatomy, additional procedure requirements, and the surgeon’s discretion. The right atriotomy was performed and once the decision for valve replacement was made, the lead position was observed. There are two surgical techniques for lead-sparing TVR. The technique outlined by Aris et al. [3] and Molina et al. [4] involves positioning the lead directly between the prosthesis and the annulus. Using this technique, there is a potential for an insulation fault to occur as a result of direct contact between the lead and the prosthesis. In addition, there is a possibility of a paravalvular leak from the potential space between the lead and the prosthesis. Thus, we performed a similar technique to that described by Yoshikai et al. [5]. Having excluded the pacemaker lead from the TV annulus, the posterior leaflet was split into two towards the annulus. With Teflon felt-supported polypropylene sutures, the pacemaker lead was encircled and kept away from the TV annulus [6, 7]. These sutures were carefully secured to prevent lead injury and facilitate unrestricted mobility. By doing so, the lead was kept away from the new valve ring, and also the potential risk of paravalvular leak was reduced. The valve sutures were then inserted into both the original annulus and the newly reconstructed annulus in order to anchor a prosthetic valve. The valve was implanted and the function of the valve was assessed and the unrestricted mobility of the pacemaker lead was once again verified to ensure the proper tension and looseness of the pacemaker lead within the right ventricle. After implanting the valve, the right atriotomy was closed and the patient was weaned off CPB (Figure 1).

Results

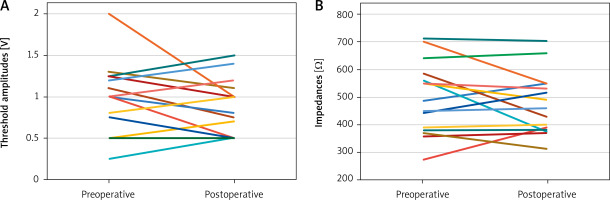

Fifteen patients who had previously had transvenous leads implanted underwent TVR. Twelve of them were female (80%) and three were male (20%). At the time of TVR, the median age and median weight were 66.5 years (58.75–71 years) and 63.5 kg (60–70 kg), respectively. Table I summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. All but 2 patients had previous cardiac operations. A detailed list of previous operations is shown in Table II. The indication for implantation of the pacemaker was ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation in 8 (53%), AV block in 4 (27%) and sick sinus syndrome in 3 (20%). The preoperative median threshold amplitude and impedance values were 1 V (0.68–1.25 V) and 518 Ω (377.5–598.7 Ω), respectively. All patients had severe TR at the time of TVR. The median LV ejection fraction was 60% (60–74%) and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) was 19 mm (16–22 mm). The median right ventricle systolic pressure (RVSP) was 60 mm Hg (55–62.6 mm Hg). All patients had severe tricuspid valve regurgitation. Six (40%) patients were NYHA class 2 and the remaining 9 (60%) were NYHA class 3 preoperatively.

Table I

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

[i] ASD – atrial septal defect, AVR – aortic valve replacement, CRT – cardiac resynchronization therapy, ICD – implantable cardioverter defibrillator, ICU – intensive care unit, LVEF – left ventricle ejection fraction, LVFS – left ventricle fractional shortening, MV – mechanical ventilation, MVR – mitral valve replacement, CABG – coronary artery bypass grafting, MVr – mitral valve repair, MVR – mitral valve replacement, SSS – sick sinus syndrome, TAPSE – tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, VF – ventricular fibrillation, VT – ventricular tachycardia.

Table II

List of previous operations of the cohort

| Previous procedures | N |

|---|---|

| ASD closure | 1 |

| AVR + MVR | 2 |

| CABG | 1 |

| DORV repair | 1 |

| MVr | 2 |

| MVR | 6 |

The median time interval between pacemaker implantation and TVR was 8.5 years (5.7–10.5 years). In terms of operative details, the median duration was 109 minutes (68–123.7 minutes). In 5 patients, TVR was performed on the beating heart. In 10 patients where diastolic arrest was achieved, the median cross-clamp time was 67 minutes (45–87 minutes). Eight patients underwent additional cardiac operation at the time of TVR. Three patients had mitral valve replacement (MVR), two had MVR + coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), one had MVR + aortic valve replacement (AVR), one had AVR, and another had surgical ablation. In terms of implanted valve choices, 2 patients had mechanical valves and 13 had biological valves. Five patients received 33 mm, 5 patients had 31 mm, 2 patients had 29 mm, 2 patients had 27 mm, and the other had 25 mm.

In all patients, the postoperative course was uncomplicated. Eleven (73%) patients required inotropic support, with a median vasoactive inotropic score of 10, and all inotropes were discontinued by 12 hours after the operation. We were able to extubate all patients in a median duration of 7 hours (6–12 hours), and the median length of stay in the ICU was 2 days (2–3 days). The hospital stay was also relatively short with a median duration of 7.5 days (6.75–15.5 days).

During the median follow-up of 3 years (2 to 5 years), there was no operative mortality. We have not encountered additional operations in the cohort during the follow-up period. Taking into account echocardiographic indices, the EF and FS values at the last follow-up were 55% (50–60%) and 26% (20–30%), which were not significantly different from the preoperative values. Nine (60%) patients were in NYHA class 1 and the remaining 6 (40%) were in NYHA class 2 at their last follow-up. Postoperative median threshold amplitude and impedance values at the last follow-up were 0.73 V (0.5–1 V) and 460 Ω (378.5–550 Ω), respectively. Variations in threshold amplitude and impedance for individual patients before and after surgery at the most recent follow-up are illustrated in Figure 2. No patients required a pacemaker lead revision during follow-up. There were no cerebral or non-cerebral embolic events, no major bleeding, no prosthetic valve endocarditis, and/or pacemaker system infection during follow-up.

Discussion

Permanent cardiac pacing is a common comorbidity in patients in need of a TVR. This topic becomes more relevant in light of the escalating global incidence of cardiac device implantations and the dire prognosis facing patients with TV lesions. Interferences between cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIED) leads and the TV apparatus have been documented in several reports [11–13]. These interferences may mostly induce TR, and on rare occasions, tricuspid stenosis. It is also known that in later phases of the disease, differentiation between lead-related and lead-associated TR can become impossible due to the prevalence of RV remodeling. Recently, the mechanisms involved for TR associated with CIEDs were separated into three categories: implantation-related, pacing-related, and device-related. The mechanism determines the pace of progression of TR that occurs after CIED implantation. Mechanical leaflet restriction or injury to the TV apparatus are the most common causes of acute TR alterations. The exacerbation of TR after the installation of a CIED can be identified at any time between 1 and 12 months, while hospitalization usually occurs after 12 months. However, all other important clinical factors that contribute to TR progression should be considered. Permanent atrial fibrillation (AF), pre- and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension, dilation of the right ventricle, and previous cardiac surgery in the aortic and/or mitral valves are equally important and should be carefully addressed [14].

When TVR is required in a patient with a transvenous PM, several solutions are available. First, the surgeon must consider explanting the PM during TVR and subsequent implantation of a new system. The new system could be epicardial, transvalvular, or coronary sinus. This is the technique most commonly used in the event of a thrombus or infection [15, 16]. An epicardial lead is not a valid option in most patients due to dense adhesions due to previous cardiac surgery in this group of patients. These alternatives can also occasionally be hindered by battery life and threshold difficulties. Research has shown that endocardial pacing systems are more effective than their epicardial counterparts. Compared to transvenous leads, ventricular chronic stimulation thresholds for epicardial leads are higher. Possible repercussions include increased energy consumption, which could accelerate battery depletion [2, 8, 17]. With transvalvular lead implantation, there is an inherent danger of causing damage to the newly implanted prosthetic valve. Complications associated with transvalvular PM leads, such as valve dysfunction, have been extensively documented [8, 11, 12, 14]. In addition, this is not applicable in patients with mechanical valves. Single coronary sinus lead pacing is a viable option in many circumstances. However, it has much higher threshold amplitudes, most likely due to the epicardial pacing site in coronary sinus leads compared to conventional endocardial pacing and an increased risk of macrodislocation of the lead. Second, the placement of the transvenous lead paravalvular during TVR surgery would be beneficial in most patients [8]. This alternative technique, first reported in 2004, included leaving the original lead outside the ring of the new TV prosthesis in a paravalvular position. It has gained popularity and the technique has been refined with further improvements [3]. Since 2014, we have implemented the use of the modified technique described by Yoshikai et al. [5], aiming to have enough tissue wrapped around the lead. Having this extra tissue around the lead, direct contact of the lead with the prosthetic valve was prevented and the likelihood of paravalvular leaking was minimized [6, 7].

The main concern with the paravalvular lead preservation technique is the increased risk of lead dysfunction, because the lead is secured in a paravalvular position in relatively close contact with the ring of the valve prosthesis [6–8]. In our cohort, there was no injury to the existing transvenous lead and the measurements of the pacemaker parameters before and after the operation were similar at mid-term follow-up. No patient required a revision of the lead and/or new lead insertion. Similarly, Molina et al. [4] presented the long-term follow-up data with the paravalvular lead preserving technique and concluded that it is not only possible to maintain a well-functioning lead, but that exceptional lead function can be sustained for many years. Furthermore, in several Mayo Clinic studies, they reported that when the lead was left in a paravalvular position during TVR, no patients required lead revisions or reoperations [12, 13]. Another study showed that paravalvular positioning of PM leads appears to be an acceptable alternative to traditional transvalvular lead positioning in terms of lead and TV prosthesis function and longevity in selected individuals at short to midterm follow-up [4, 7, 8]. It should also be kept in mind that lead dysfunction could be remedied by implanting a new PM lead through standard ways such as the coronary sinus or crossing the TV while leaving the paravalvular lead alone.

Another theoretical disadvantage with this technique is that removing the lead in the case of an infection in the future will be difficult, if not impossible, without harming the TV. Due to the absence of endocarditis cases in our cohort during the follow-up period, we cannot adequately address this concern. Similarly, in other studies that used the paravalvular technique, no patient developed endocarditis [3–8, 11, 12]. It should be noted that the risk of infection is considerably elevated during the generator replacement process compared to the initial implantation phase. Therefore, it is critical to replace generators with extreme caution to prevent infection.

This study is limited by the fact that it was conducted retrospectively and observationally at a tertiary referral center and with a small sample size over an extended period of time. As a consequence, inconsistent patient selection and management ensued. In addition, no comparison was made with an alternative lead implantation technique. Comprehensive statistical analysis was ultimately constrained by the number of fatalities, reoperations, and complications such as endocarditis. Potential future multicenter research could help address these constraints.