Introduction

Menopause is defined as the permanent cessation of menstruation, determined retrospectively after 12 consecutive months of amenorrhoea. The period leading up to this point is known as perimenopause, characterised by menstrual irregularity and fluctuating hormone levels. Perimenopause typically starts several years before the final menstrual period and concludes 12 months after the last menstrual period, marking the onset of menopause. Postmenopause is the phase of life that follows menopause [1]. This stage of life is characterised by a diverse range of experiences on a bio-psycho-social level [2, 3].

The typical age for natural menopause ranges 45– 55 years [4]. However, this age can vary by geographic region [5], with influencing factors such as genetics, the age of first menstruation, lifestyle, and socio-economic status [6].

The onset of menopause brings about various changes and symptoms, which can be divided into 3 categories: somatic, vasomotor, and psychological [7]. Common somatic symptoms include headaches, dizziness, fatigue, as well as joint and muscle pain. Vasomotor symptoms typically consist of hot flashes and night sweats, while psychological symptoms often involve sleep disturbances, depression, irritability, and memory impairment. It is also important to note symptoms related to sexual function, such as vaginal dryness and shifts in sexual desire [2, 8].

The term “attitude” refers to the tendency to adopt a positive or negative stance toward a person, object, or idea, which is expressed through emotions, thoughts, or behaviours [9, 10]. Attitude is characterised by its valence – positive or negative – and its intensity [10]. Attitude toward menopause is defined as a person’s opinions and feelings about menopause as a phenomenon, rather than their own experience of it [11]. These beliefs can apply to symptoms or changes occurring during the menopausal period, as well as to the life stage of aging itself [12].

The perception of menopause varies depending on geographic location, culture, traditions, values, or level of education [12–14]. Differences in the role of women in society, the significance of aging both for the woman and for society, and the impact of and ways of coping with symptoms all significantly influence the image of menopause. It can be viewed in terms of loss, for example, of youth or reproductive capacity [15, 16], but also as a form of relief, reducing the risk of pregnancy or the cost of sanitary products [17].

Attitudes toward menopause are often classified as positive, negative, or neutral in psychological research [18, 19]. Studies show that women in the premenopausal or perimenopausal stages are much more likely to hold negative attitudes, in contrast with women who have already gone through menopause, who tend to have more positive attitudes toward menopause [11, 19]. It is suggested that the type of attitude towards menopause may influence how women experience this phase of life [18], with negative attitudes toward menopause being associated with a higher severity of menopausal symptoms [14, 16].

Life satisfaction is defined as a feeling of contentment or fulfilment experienced by an individual as a result of a multifactorial evaluation of their own life [20]. It is an assessment of life satisfaction that arises from a cognitive evaluation of one’s own situation in relation to personal standards [21]. Many factors influence life satisfaction during menopause, including education, social support, marital status, and economic status [22]. It is also a time of increased risk for the onset of depression [23]. Research indicates that menopausal symptoms often negatively impact women’s perceived quality of life, with more severe symptoms correlating with lower life satisfaction [22, 24, 25]. Positive attitudes toward menopause are linked to fewer menopausal symptoms, while negative attitudes are associated with more intense symptoms and decreased life satisfaction [11, 12, 26].

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is recognised as the most effective method for managing symptoms associated with the menopausal transition [27, 28]. Research indicates that HRT enhances the well-being and emotional state of women in the perimenopausal phase [28]. This therapy helps alleviate menopause-related symptoms such as night sweats, hot flashes, and sleep disturbances, as well as joint and muscle pain. Additionally, the therapy also improves women’s sexual functioning and reduces genitourinary symptoms at this stage of life [27–29].

Growing interest in menopause research provides a better understanding of connections between attitudes towards menopause and menopausal symptoms [11, 16], menopausal symptoms and life satisfaction [2, 24], and attitudes towards menopause and satisfaction with life [26]. A noticeable gap exists in the comprehensive understanding of relationships between menopause symptoms, women’s attitudes toward menopause, and their overall satisfaction with life. Research on this topic offers valuable insights into how women navigate this transitional phase. The findings can have practical implications for improving healthcare strategies by customising support and educational efforts. Furthermore, the results of this research can help design interventions to enhance life satisfaction, encourage positive attitudes, and support effective coping mechanisms during menopause.

Material and methods

The aim

The aim of the study is to analyse the relationship between menopausal symptoms (psychological, somatic- vegetative, and urogenital symptoms) and attitudes towards menopause (overall, positive, and negative) in relation to life satisfaction among menopausal women.

Hypothesis

The menopausal phase differentiates the assessment of menopausal symptoms, attitudes towards menopause, and life satisfaction among women.

Use of HRT differentiates the assessment of menopausal symptoms, attitudes towards menopause, and life satisfaction.

The assessment of menopausal symptoms significantly explains attitudes towards menopause, with more positive symptom assessments leading to more positive attitudes towards menopause.

The assessment of menopausal symptoms and attitudes towards menopause affect life satisfaction, where more positive symptom assessments and attitudes are associated with greater life satisfaction.

Attitudes towards menopause mediate the relationship between the assessment of menopausal symptoms and life satisfaction.

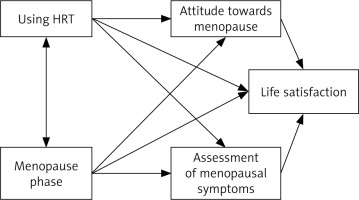

The relationships between all the analysed variables are presented in Figure 1.

Tools

In the study, sociodemographic data were collected using a dedicated questionnaire, alongside 3 primary research instruments. The questions in the questionnaire defined the gender of the examined person, age (40– 65 years), current phase of menopause (premenopause – regular menstrual bleeding in the last 12 months, perimenopause – irregular menstrual bleeding in the last 12 months, and postmenopause – no menstrual bleeding in the last 12 months), type of education, population of their area, use of hormone replacement therapy, economic status, marital status, childbearing, and diagnosis or lack of depression.

The second tool, the menopause rating scale by Heinemann, was employed to evaluate the severity of menopausal symptoms. The scale consists of 11 questions regarding 11 specific symptom groups, which were divided into 3 categories: psychological symptoms, somatic-vegetative symptoms, and genitourinary symptoms. The third instrument, the skala oceny menopauzy (menopause attitude scale) by Bielawska-Batorowicz [7], was used to assess participants’ general attitudes toward menopause. It is important to note that this tool evaluates overall perceptions of menopause, rather than personal experiences. The scale consists of 35 sta- tements regarding menopause, with 15 positive, 15 negative, and 5 neutral statements. The final tool used was the satisfaction with life scale, which measures overall life satisfaction. The questionnaire contains 5 statements relating to the respondent’s life to date.

Participants

The initial sample consisted of 316 participants. After applying the inclusion criteria (gender of the participant, age, consent for participation) and exclusion criteria (questionnaire completion and a confirmed lack of diagnosis of depression), the final sample comprised 267 wo- men aged 40–65 years (M = 49.6, SD = 4.7). Among the participants, 60% held a higher education degree, and over one-third resided in urban areas. The majority (70%) were married, and 70% of the respondents reported a favourable economic status. Only approximately 15% of participants were undergoing hormonal replacement therapy. The sample was stratified into 3 groups corresponding to different menopausal stages: 85 women in premenopause, 81 in perimenopause, and 101 in postmenopause, with each group being similar in size.

Course of research

The research was conducted in the period May–July 2021. The research has approval from the Ethical Commission for Research in the University of Szczecin, Psychology Institute, number KB 7/2021. The data were collected anonymously from various groups on social media platforms. The survey was preceded by an explanation provided by the authors regarding the purpose of the study, the age range of participants, the assurance of anonymity, and the participants’ right to withdraw at any point during the process.

Results

Menopause phase and menopausal symptoms assessment, attitude towards menopause, and life satisfaction

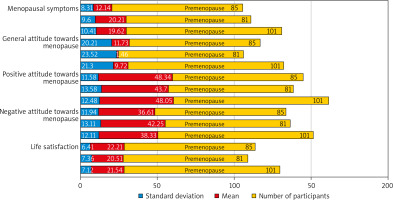

A one-way ANOVA was conducted. The independent variable was the phase of menopause, while the dependent variables were the perception of menopausal symptoms, generalised attitude towards menopause, and life satisfaction. The results are presented in Figure 2 below.

The analysis revealed that the assessment of menopausal symptoms significantly differs depending on the phase of menopause [F(2,264) = 18.735; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.12]. Post hoc comparisons with Holm’s correction for multiple comparisons were performed. The results indicated that premenopausal women’s assessment of menopausal symptoms significantly differed from those of perimenopausal women [t(264) = –5.387; p < 0.001; g = –0.66] and postmenopausal women [t(264) = –5.265; p < 0.001; g = –0.65], with women in the premenopausal phase assessing menopausal symptoms significantly more positively than women in the other 2 groups. However, the difference between perimenopausal and postmenopausal women was statistically insignificant.

The analysis reveals that generalised attitudes toward menopause significantly differ depending on the phase of menopause [F(2,264) = 5.267; p = 0.006; η2 = 0.038]. The results indicate that premenopausal women significantly differ in their generalised attitudes toward menopause from perimenopausal women [t(264) = 3.054; p = 0.007; g = 0.38]. The difference between premenopausal and postmenopausal women was negligible and statistically insignificant. At the same time, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women significantly differed in their attitudes toward menopause [t(264) = –2.558; p = 0.022; g = 0.31]. The findings reveal that women in the perimenopausal phase demonstrate the most negative scores on the generalised attitude towards menopause scale compared to those in other menopausal phases.

Detailed analysis revealed that the positive attitude toward menopause significantly differs depending on the phase of menopause [F(2,264) = 3.605; p = 0.029; η2 = 0.027]. Post hoc comparisons with Holm’s correction showed that premenopausal women significantly differed in their positive attitude toward menopause from perimenopausal women [t(264) = 2.379; p = 0.054; g = 0.29]. Perimenopausal women also significantly differed from postmenopausal women in this regard [t(264) = –2.321; p = 0.054; g = –0.29]. However, the difference between premenopausal and postmenopausal women was negligible. The presented analysis shows that positive attitudes were the lowest among perimenopausal women and consistent across the other stages.

The analysis also revealed that the level of negative attitude toward menopause significantly differed depending on the phase of menopause [F(2,264) = 4.525; p = 0.012; η2 = 0.033]. Post hoc comparisons with Holm’s correction showed that premenopausal women significantly differed in their negative attitude toward menopause from perimenopausal women [t(264) = –2.934; p = 0.011; g = –0.36]. Perimenopausal women also differ in their negative attitude toward menopause from postmenopausal women [t(264) = 2.125; p = 0.069; g = 0.26]. The difference between premenopausal and postmenopausal women was statistically insignificant, showing that the perimenopausal group had the highest mean average in the negative attitude component.

The analysis reveals that there are no significant differences in life satisfaction among women in different phases of menopause [F(2,264) = 1.254; p = 0.277; η2 = 0.009].

Using hormone replacement therapy and assessment of menopausal symptoms, attitude towards menopause, and life satisfaction

An independent sample Student t-test was conducted. Data from n = 85 premenopausal women were excluded from the analysis based on the assumption that HRT is used during the peri- and postmenopausal phases. The results obtained are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Summary of the results of Student’s t-test for comparing life satisfaction, attitudes towards menopause, and assessment of menopausal symptoms in women using and not using hormone replacement therapy during menopause

Women using HRT showed better assessment of menopausal symptoms [t(180) = 1.72; p = 0.044; g = 0.329], significantly higher life satisfaction [t(180) = –2.108; p = 0.018; g = –0.404], and less negative general attitude toward menopause [t(180) = –1.723; p = 0.043; g = –0.33]. Particularly interesting is the fact that the difference in the components of attitudes toward menopause was found only in terms of negative components [t(180) = 2.579; p = 0.005; g = 0.494], while positive attitudes were statistically insignificant. This indicates that women using HRT do not necessarily have a better overall attitude toward menopause, but rather a less negative attitude toward it.

Interrelationships between menopausal symptom ratings, attitudes towards menopause, and life satisfaction

The correlation analysis conducted in the study revealed significant interdependencies between the assessment of menopausal symptoms, attitudes toward menopause, and life satisfaction. The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Summary of the correlation between variables in the model

A strong negative correlation emerged between life satisfaction and the assessment of menopausal symptoms [r = –0.488; p < 0.001; CI95 = (–1; –0.407)]. Similarly, the assessment of menopausal symptoms was found to strongly correlate with the generalised attitude towards menopause [r = –0.657; p < 0.001; CI95 = (–1; –0.596)]. However, the assessment of menopausal symptoms better explains the negative component of attitudes towards menopause [r = 0.706; p < 0.001; CI95 = (0.753; 1)] than the positive component [r = –0.444; p < 0.001; CI95 = (–1; –0.359)].

Additionally, a significant positive correlation was found between generalised attitudes towards menopause and life satisfaction [r = 0.596; p < 0.001; CI95 = (0.526; 1)]. A detailed analysis of the relationship between life satisfaction and both positive and negative attitudes towards menopause showed that life satisfaction is better explained by negative than by positive attitudes towards menopause.

The mediating role of attitudes in shaping the relationship between menopausal symptom ratings and life satisfaction

A mediation model analysis was conducted, and a structural equation model was established. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Summary of the structural equation model analysis results for estimating the indirect effect of attitudes towards menopause on shaping the relationship between the assessment of menopausal symptoms and life satisfaction

| The path | Direct effect | Indirect effect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | LB | UB | b | SE | LB | UB | |

| Menopause symptoms assessment ≥ life satisfaction | –0.117 | 0.044 | –0.204 | –0.030 | –0.219 | 0.033 | –0.283 | –0.154 |

Generalised attitudes towards menopause were a significant partial mediator of the relationship between the assessment of menopausal symptoms and life satisfaction in the women studied [b = –0.031; standard error for mediation estimator (SE) = 0.005; p < 0.001; CI95 = (–0.042; –0.021)]. This indicates that attitudes towards menopause can only partially explain the relationship between menopausal symptom assessment and life satisfaction, and the process shaping this relationship is more complex, probably involving other significant factors mediating the relationship between menopausal symptom ratings and life satisfaction in women. The mediation model was expanded to include the assumption that both positive and negative attitudes towards menopause mediate the relationship between menopausal symptom ratings and life satisfaction.

Together, both aspects of attitudes towards menopause reveal significant and total mediation effects on the relationship between menopausal symptom ratings and overall life satisfaction [b = –0.035; SE = 0.005; p < 0.001; CI95 = (–0.048; –0.024)]. Attitudes towards menopause, understood as both the positive and negative aspects of attitude, explain about 73% of the relationship, and in the entire population of perimenopausal women, the mediation effect ranges 62–89% [R2MED = 0.729; CI95 = (0.623; 0.889)].

A detailed analysis of both aspects of attitudes towards menopause indicates that both the negative [b = –0.028; SE = 0.005; p < 0.001; CI95 = (–0.039; –0.013)] and positive [b = 0.009; SE = 0.003; p < 0.001; CI95 = (–0.016; 0.004)] attitudes towards menopause significantly mediate the relationship between menopausal symptom assessment and life satisfaction. However, it is noticeable that the negative aspect of attitudes towards menopause better explains the mechanism of the relationship between menopausal symptom assessment and life satisfaction [R2MED = 0.667; CI95 = (0.574; 0.813)] than the positive aspect [R2MED = 0.409; CI95 = (0.356; 0.571)].

Discussion

Menopause is a natural phase in a woman’s life. Research has shown that the severity of menopausal symptoms can fluctuate throughout the menopausal transition. In the study referenced, women in the premenopausal stage reported the lowest severity of symptoms, while those in subsequent stages exhibited symptoms at comparable levels. This finding aligns with existing literature, which suggests that menopausal symptoms may subside after menopause, although they can persist for several years post-menopause [27].

Additionally, the study found that women in the perimenopausal phase exhibited the most negative attitudes toward menopause, whereas attitudes in the premenopausal and postmenopausal phases were comparable. Existing literature indicates that attitudes toward menopause are influenced by a variety of factors, including education, social background, ethnicity, and cultural context [13, 14]. It is plausible that women in the premenopausal stage experience fewer symptoms than those in other stages. Moreover, younger women may have greater access to educational resources and health information, which could influence their perceptions of menopause. This potentially explains the results obtained in the study. Furthermore, postmenopausal women may have developed a broader perspective and emotional distance from the event, experiencing less anxiety about menopause. This may account for their more neutral or accepting attitudes in comparison to women in the perimenopausal phase.

In the process of analysing the results, it was decided to break down general attitude towards menopause into 2 core components: positive attitudes and negative attitudes. The analysis revealed that positive attitudes were the lowest among perimenopausal women and consistent across the other stages. Similarly, the negative attitude component was the highest in the perimenopausal group, while it was less negative in the remaining groups. These findings may be attributed to the perception of menopause as a loss of youth or fertility, or general negative narration about menopause or ageing [15, 16]. Furthermore, the lack of education and the persistent taboo surrounding menopause may contribute to the limited development of positive attitudes toward this life stage.

The study also examined participants’ life satisfaction. Interestingly, the results showed no statistically significant differences in life satisfaction across all menopausal phases, with all groups reporting average levels of satisfaction. This outcome contrasts with much of the existing research, which often links the perimenopausal phase with more severe symptoms and lower life satisfaction [2, 24]. However, this finding may be explained by the fact that life satisfaction tends to decline around the time of menopause due to various factors, such as changes in body image [19], reduced sexual satisfaction [29], and significant life events typical of this period, such as the death of parents or a partner, among other potential causes.

This study also examined the variation in menopausal symptoms, attitudes towards menopause, and life satisfaction between women using HRT and those not using it. Premenopausal women were excluded from the analysis. The findings indicated that women undergoing HRT reported significantly less severe menopausal symptoms and higher life satisfaction compared to those not receiving HRT. This difference may be attributed to the fact that HRT is often prescribed to women experiencing more severe menopausal symptoms that substantially impact their daily lives. Consequently, the reduced severity of symptoms among HRT users could explain their enhanced life satisfaction, suggesting that symptom severity has an influence on overall life satisfaction.

Furthermore, the research demonstrated that women not using HRT exhibited more negative general attitudes towards menopause compared to HRT users. However, further analysis revealed no significant difference between the 2 groups regarding positive component of attitudes towards menopause. Interestingly, when assessing the negative component of attitudes, HRT users reported a lower intensity of negative attitudes compared to non-users.

This finding implies that the attitudes towards menopause of women using HRT were comparatively less negative than women not using HRT. This result becomes particularly noteworthy when contrasted with the earlier findings in the study, which showed that perimenopausal women had both the lowest positive attitudes and the highest negative attitudes towards menopause. This suggests that the use of HRT is associated with a reduced intensity of negative attitudes towards menopause.

Further analysis of the results indicated a strong negative correlation between the severity of menopausal symptoms and life satisfaction. This finding aligns with existing literature, which demonstrates that more severe menopausal symptoms are associated with lower life satisfaction [23, 24], particularly in relation to physical and social aspects of menopausal symptoms [2]. Additionally, a positive correlation was observed between the severity of menopausal symptoms and attitudes towards menopause. These results are consistent with findings from other studies [11, 12, 30]. However, it remains unclear whether more severe menopausal symptoms lead to more negative attitudes, or if negative attitudes intensify the perception of symptom severity [11].

Moreover, the study revealed a positive association between overall attitudes towards menopause and life satisfaction. While few studies have explored this specific relationship, most research has focused on the links between attitudes toward menopause and symptom severity, or between symptom severity and life satisfaction. This underscores the need for further investigation into the complex interplay between menopausal attitudes and life satisfaction.

Furthermore, the study suggests that general attitudes toward menopause partially mediate the relationship between the assessment of menopause symptoms and life satisfaction. Since these attitudes only partially explain the connection, further analyses were conducted. The results show that attitudes significantly influence the relationship between symptom assessment and life satisfaction. While a positive attitude has some impact, negative attitudes have a much stronger effect. In summary, the perception of menopause symptoms, which refers to the discomfort and challenges of physical and psychological changes, affects life satisfaction mainly through the shaping of attitudes toward these negative changes.

This study has several limitations. The sample was highly heterogeneous, with 60% having higher education, 43% living in cities with over 250,000 residents, and 70% reporting a good economic status. While comparisons were made between women using and not using HRT, about 85% of participants were not using HRT, which may have affected the results. The online survey method, shared through social media, also restricted participation to women with internet access and digital literacy, limiting the findings’ generalisability. Additionally, mediation effects were not analysed over time, which could have provided more comprehensive insights.

Despite these limitations, the study offers valuable insights into the relationships between menopausal symptoms, attitudes, and life satisfaction. Understanding the significant influence of menopause attitudes on life satisfaction, and the role of symptom evaluation as a mediator, can help healthcare professionals and support providers. Educational efforts to increase knowledge and normalise menopause symptoms could be beneficial, potentially leading to more positive attitudes and improved life satisfaction and symptom evaluation.

Future research should explore factors shaping attitudes towards menopause, especially women’s knowledge and that of their close associates. Additionally, studying the influence of partners’ attitudes and knowledge on women’s menopausal experiences could offer further valuable insights.

Conclusions

The menopausal phase influences the assessment of menopausal symptoms and attitudes towards menopause, with women in the premenopausal phase evaluating these symptoms as the least severe, representing the most negative generalised attitudes.

Hormone replacement therapy differentiates the assessment of menopausal symptoms, life satisfaction, and attitudes toward menopause, with women using HRT having more positive assessment of menopausal symptoms, a less negative attitude toward menopause, and greater life satisfaction.

A negative correlation is observed between the assessment of menopause symptoms and general attitudes toward menopause.

A strong negative correlation exists between the perception of menopause symptoms and life satisfaction, whereas a positive correlation is found between general attitudes toward menopause and life satisfaction.

Generalised attitudes toward menopause partially mediate the relationship between the assessment of menopausal symptoms and perceived life satisfaction.