Atrial fibrillation hybrid management in light of multidisciplinary patient-oriented atrial fibrillation management

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, with increasing prevalence, significant socioeconomic burden, and everyday impairment of quality of life in diagnosed patients [1, 2]. To adequately address the multifactorial challenges associated with AF management, a patient-centered, integrated approach was developed, broadly known as AF-CARE (Figure 1). It consists of four main principles: (C)omorbidity and risk factor management, (A)void stroke and thromboembolism, (R)educe symptoms by rate and rhythm control, and (E)valuation and dynamic reassessment [3]. Although pharmacologic therapy remains foundational, its suboptimal efficacy, especially in persistent arrhythmias, has fueled the evolution of interventional strategies, each with unique benefits and constraints [3]. In light of this approach, hybrid management of AF serves as a tool for both avoidance of stroke and thromboembolism by left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) and reduction of symptoms by rate and rhythm control achieved through double-approach hybrid ablation [3]. Additionally, it may lead to complete treatment of AF with lifelong prevention of cryptogenic strokes and other thromboembolic events. To better understand the significance of the hybrid management of AF, the two aforementioned components should be analyzed in detail.

Definitions of hybrid arrhythmia treatment

Hybrid arrhythmia treatment encompasses a spectrum of approaches that integrate surgical and catheter-based interventions, either concurrently or sequentially [4]. Standard hybrid techniques include:

thoracoscopic epicardial ablation followed by transcatheter touch-up mapping and ablation;

concomitant surgical pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) and electrophysiological testing, with possible endocardial supplementation using “touch-up” techniques.

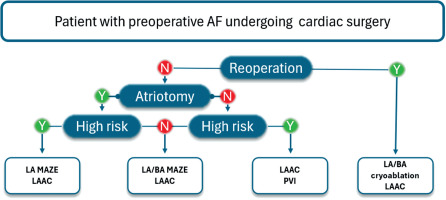

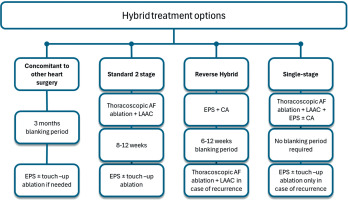

Multiple procedural timing (0–6 months) strategies exist within hybrid therapy, each requiring close collaboration between cardiac surgeons and electrophysiologists to ensure optimal outcomes (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Flowcharts for different hybrid arrhythmia treatment options

AF – atrial fibrillation, CA – catheter ablation, EPS – electrophysiological study, LAAC – left atrial appendage closure; blanking period after each procedure might vary from 2 to 3 months; however, in the case of very symptomatic recurrences despite escalation of antiarrhythmic therapy and cardioversion, the second stage, especially with persistent macroreentrant tachycardias, could be performed earlier

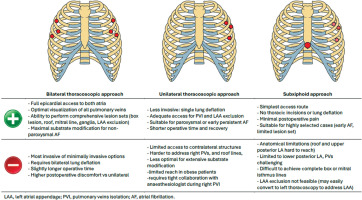

The choice of timing strategy is often determined by the operator’s expertise and preferences, institutional resources, operating room limitations, reimbursement policies, and, more importantly, patient-related factors such as comorbidities and anatomical features [5, 6]. The strengths and weaknesses of different timing strategies are summarized in Figure 3.

Although hybrid treatment is gaining recognition, it is essential to evaluate the superiority of hybrid ablation over stand-alone surgical or “catheter only”-based ablation, and to determine the most appropriate treatment modality for each patient individually. Shared patient decision-making remains key to optimizing long-term success [3].

Indications and contraindications for hybrid atrial fibrillation ablation

Hybrid ablation should not be regarded as a simple alternative to catheter-based therapy but rather a specialized, escalation-level intervention dedicated to a specific subset of patients. As stated in the 2024 ESC Guidelines, hybrid ablation carries a class IIa recommendation for patients with symptomatic persistent AF refractory to antiarrhythmic drugs (AAD) to prevent symptoms, recurrence, and progression of AF. Class IIb is assigned to performing hybrid ablation in symptomatic paroxysmal AF refractory to AADs and particularly in those with failed prior catheter ablation within a shared decision-making team [3]. This proves a growing recognition of the role hybrid ablation can play in the comprehensive management of AF. Key indications for hybrid ablation include:

Symptomatic non-paroxysmal AF (persistent or long-standing persistent AF).

Patients with documented epicardial substrate or posterior wall involvement inaccessible by endocardial means.

Failure of ≥ 1 catheter ablation procedure for AF.

Large left atrium (e.g., ≥ 50 mm diameter or left atrial volume index (LAVI) ≥ 28 ml/m2).

Confirmed, recurrent, or suspected left atrial appendage (LAA) thrombus (absolute contraindication to catheter ablation).

Oral anticoagulant (OAC) contraindications (e.g., severe bleeding, sports injury risk, systemic intolerance).

Pre-surgical planning requiring OAC discontinuation (e.g., renal transplantation).

Patient preference for epicardial LAAC and durable lesion sets.

Hybrid ablation is also beneficial when rhythm control is a prerequisite for left ventricular reverse remodeling (e.g., tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy) in patients where permanent pacemaker implantation is not desirable. Relative contraindications include:

Advanced frailty or inability to tolerate general anesthesia.

Severely impaired respiratory function (e.g., advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), though minimally invasive strategies like unilateral access or extracorporeal support may be feasible [7].

Severely reduced EF (< 25%) unless AF is the primary suspected cause (tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy).

Ongoing active infection, unstable coronary disease, or severe pulmonary hypertension.

Limitations to surgical access AF ablation include: severe chest and vascular anomalies, previous thoracic or cardiac surgery, and previous severe chest trauma and injuries. Some of the limitations are not predictable from earlier exams and diagnostic imaging, such as pericardial or pleural adhesions. Shared decision-making through a multidisciplinary electrophysiology (EP)-heart team is crucial to guide patient selection and align treatment with patient values and clinical realities.

Advantages and limitations of stand-alone and hybrid approaches in arrhythmia treatment

Stand-alone approach

Surgical arrhythmia treatment has advanced from the classic Cox-Maze III procedure to minimally invasive formats, performed through various approaches, including thoracoscopic and subxiphoid access (Figure 4).

Thoracoscopic epicardial ablation enables PVI and the creation of adjunctive lesion sets targeting left atrial substrates. Robotic-assisted techniques offer precision and reduced surgical trauma [8]. Concomitant ablations during valve or CABG surgery are efficient opportunities for integrated rhythm control. Catheter ablation is effective in paroxysmal AF and supraventricular tachycardias, utilizing 3D electroanatomical mapping [9]. However, its limitations include difficulty achieving transmurality and incomplete lesion sets in persistent AF [8]. Energy modalities include radiofrequency, including high voltage short duration techniques, cryoablation, laser, and emerging pulsed field ablation (PFA), which offers more safety and promising efficacy [10]. Each of the above approaches provides unique benefits for AF treatment; however, it is also associated with different limitations and complication profiles.

Hybrid approach

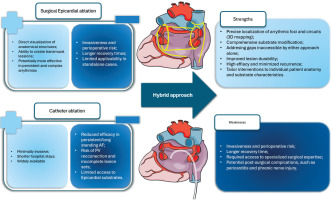

Hybrid ablation combines the strengths of both surgical and catheter-based approaches, eliminating most of their respective limitations simultaneously (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Hybrid ablation as a synthesis of surgical and catheter ablation for successful atrial fibrillation treatment

AF – atrial fibrillation, PV – pulmonary vein.

This technique enables comprehensive access to both endocardial and epicardial substrates, improves success in persistent AF, reduces recurrence, and encourages multidisciplinary collaboration [11]. Moreover, it is adaptable based on intraoperative findings and patient anatomy, optimizing ablation strategies. It should be acknowledged that previous reports point to the fact that the hybrid approach was associated with a slightly increased incidence of complications when compared to catheter ablation alone [12]. With more recent data, the complication rates are dropping, but certainly deserve further investigation [13].

Rationale for hybrid treatment

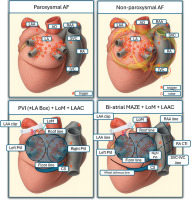

Persistent forms of AF involve complex pathophysiology with both triggers and substrate-related drivers, like rotors and fibrosis [14]. While paroxysmal AF is largely trigger-based and suitable for catheter ablation, non-paroxysmal AF benefits from comprehensive lesion creation (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Triggers in paroxysmal and non-paroxysmal AF and ablation targets

AF – atrial fibrillation, AO – aorta, CS – coronary sinus, CTI – cavo-tricuspid isthmus, IVC – inferior vena cava, LA – left atrium, LAA – left atrial appendage, LAAC – left atrial appendage closure, LoM – ligament of Marshall, PVI – pulmonary vein isolation, RA – right atrium, RAA – right atrial appendage, SVC – superior vena cava.

Surgical ablation, typically via the thoracoscopic approach, is better suited for targeting both triggers and substrates, and achieving transmural and durable lesions, including epicardial structures that may not be accessible via the endocardial approach [9]. Hybrid therapy has emerged as a promising strategy, combining the strengths of both techniques: surgical durability with catheter precision. Importantly, early preoperative planning enables an individualized patient approach and the integration of an appropriate rhythm management strategy into the overall surgical plan. Postoperatively, referral for an electrophysiological study (EPS) is essential to verify the completeness of the ablation lines and perform a “touch-up” ablation if necessary. The multidisciplinary, staged approach optimizes procedural outcomes, as shown by improved arrhythmia-free survival, especially in persistent AF [11].

Evidence-based review of hybrid arrhythmia treatment

Surgical versus catheter ablation

Three trials compared surgical and catheter ablation. Two trials compared the efficacy, and one was focused on quality of life outcomes [15–17]. In terms of efficacy, surgical ablation has been proven to be superior to catheter ablation (60–65% AF freedom vs. 36.5–46%), although effectiveness is paired with an increased risk of complications. It should be noted that in the long-term observation of patients from the FAST trial, the increased risk of complications was not maintained, but so was the observation regarding increased effectiveness of rhythm restoration [15]. No differences were observed in terms of quality of life; however, the surgical ablation group experienced more significant complications.

Hybrid versus catheter ablation

There is a limited number of trials directly comparing hybrid ablation with catheter ablation. In two studies, the thoracoscopic approach was used for epicardial ablation, resulting in higher rates of AF freedom in the hybrid ablation population (71.6–89% vs. 39.2–41%) [11, 13]. This observation was sustained in a 3-year follow-up. Additionally, no significant difference in complication rate was observed during the 3-year follow-up. In one trial using a subxiphoid approach, the hybrid approach was superior; however, the difference between the two groups was less pronounced (67.7% vs. 50%), still statistically significant in favor of hybrid ablation. One study reported significantly lower AF recurrence in the hybrid group (29.6% vs. 34.9%); however, the hybrid approach was associated with more extended hospital stays (11 days vs. 4 days) [18]. The type of AF was identified as the primary determinant of hybrid approach success, with better outcomes observed in paroxysmal AF following failed catheter ablation and in persistent type with relatively short AF episodes [19].

The CAPLA trial was performed to investigate the impact of additional posterior wall isolation in addition to PVI during catheter ablation [20]. There were no significant differences between the above group in terms of freedom from AF at 12 months, which additionally underlines the importance of the epicardial component during hybrid ablation, as in the CONVERGE trial [21].

A recent meta-analysis by Aerts et al. compared hybrid thoracoscopic with surgical thoracoscopic AF ablation [22]. Based on results from 53 studies encompassing 4,950 patients, no significant differences in short-term mortality and stroke were found. However, long-term freedom from atrial arrhythmias was higher in the hybrid group (HR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.43–0.83).

Role of pulsed field ablation in hybrid procedures

PFA is rapidly becoming a cornerstone of contemporary catheter ablation, owing to its tissue specificity, short procedure time, and superior safety profile. These advantages are now extending to the hybrid setting. While most studies of PFA have focused on stand-alone procedures, early data confirm its utility in the second stage of hybrid ablation. Eltsov et al. demonstrated successful endocardial PFA completion of epicardial lesion sets in all 11 patients with 100% sinus rhythm maintenance at 12 months and no procedural complications [23]. Another study comparing hybrid-convergent ablation to PFA showed similar rhythm outcomes but superior safety in the PFA arm, although LAAC was not performed in that trial [24]. Surgeons and electrophysiologists should collaborate in selecting the optimal energy modality for the second stage. If PFA is available and suitable, it should be used without hesitation to complete posterior wall isolation or touch-up lines. Hybrid therapy does not imply a limitation to older technologies but rather a flexible platform to integrate the best tools from both disciplines, evolving with innovation for the patient’s benefit.

Procedure-related complications and management

The hybrid ablation procedure combines the risk profile of both surgical and catheter ablation techniques. While complication rates have declined with increased experience, early identification and proactive management remain essential. Strategies to prevent and detect complications include: a) preoperative imaging: 3D/contrast enhanced (angio) computed tomography, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), and spirometry (for unilateral lung ventilation capability); b) intraoperative tools: TEE guidance, phrenic nerve direct visualization, electroanatomic mapping; c) postoperative monitoring: 24-hour ICU monitoring, chest tube control, chest X-ray (to exclude pleural effusion or pneumothorax), early transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and inflammatory markers and d) active prevention of post-procedural pericarditis and post-cardiotomy syndrome [25]. Supplementary Table SI lists the most common complications of either/each approach.

Hybrid ablation as a concomitant procedure

The tailored AF approach can be integrated into a broad spectrum of cardiac procedures. Regardless of the primary surgical implication, AF ablation and LAAC may be safely implemented without increased procedural risk [26, 27]. Studies have shown that concomitant surgical ablation improves long-term survival, despite baseline surgical risk, implying that AF treatment should be considered an integral part of cardiac surgery rather than an optional adjunct [28]. In mitral valve surgeries, left atriotomy provides safe access to perform LAAC and LA or bi-atrial MAZE effectively. Given the proven contribution to arrhythmia control, right atrial lines should also be considered standard in patients undergoing tricuspid valve repair and a viable option in other settings [29]. Compared to LA MAZE, concomitant bi-atrial ablation is associated with higher efficacy; however, the patient’s profile and perioperative risk should be considered due to the increased risk of procedural complications [30].

Even though reoperations present additional procedural challenges due to adhesions and altered anatomy, e.g., the presence of coronary bypass grafts, LAA can still be successfully occluded, following careful patient profile assessment [31]. Cryoablation provides effective lesions with minimized tissue trauma, rendering it especially well-suited for reoperations [32, 33]. Even minimally invasive approaches, such as minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass, do not preclude effective ablation and LAA [34]. Targeted strategies can provide significant rhythm control, despite no left atrial endocardial access. Decisions for optimal AF treatment during cardiac surgery can be made based on the flowchart presented in Figure 7 [30].

Postoperative monitoring and follow-up

Postoperative care after hybrid or surgical AF ablation mirrors that of patients undergoing minimally invasive cardiac surgery. A chest tube is routinely inserted to manage the pleural space and detect bleeding or effusion. Patients are typically monitored in an ICU for 24 hours. Standard pathway includes: pain control and port-site analgesia, removal of drains typically on postoperative day 1, and discharge on day 2–3 if the patient remains stable. The initial follow-up visit is scheduled at 7 days for wound check and ECG. The cardiologist handles the patient afterwards: visit is scheduled at 30 days: rhythm control, medication titration, echo for pericardial effusion. Second-stage EPS, mapping, and potential touch-up catheter ablation follow at 1–3 months if the staged hybrid protocol is followed. AF recurrence within the 3-month blanking period should not be interpreted as ablation failure; in fact, recurrence during this window is expected as ablation lines mature and the healing process ensues [4]. A designated blanking period between the surgical and transcatheter stages of hybrid ablation is considered beneficial, as it allows for complete stabilization and maturation of epicardial lesion sets. This interval facilitates accurate identification of conduction gaps, which can then be effectively addressed through targeted endocardial touch-up during the catheter-based procedure. Importantly, the addition of peri-mitral and tricuspid isthmus lines, as well as coronary sinus ablation, should be reserved for patients who exhibit clinical or inducible left or right atrial flutter during the blanking period or at the time of catheter ablation. Notably, only approximately 10–15% of patients appear to be at risk for such arrhythmias, supporting a selective rather than routine approach to these supplementary ablation lines [35, 36]. Importantly, stroke risk remains controlled during blanking by dual strategy: OAC + epicardial LAAC [37].

Rationale for left atrial appendage closure during hybrid ablation

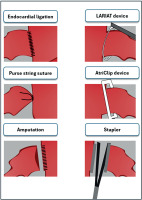

LAA is the primary cardioembolic source of stroke, due to its anatomical properties and blood flow obstruction, especially in its distal part [38–40]. In patients with AF, blood flow disturbance in LA further promotes thrombus formation in the LAA, which can be released to systemic circulation and cause fatal ischemic complications [41]. Based on these observations, several techniques, both surgical and transcatheter, as well as epicardial and endocardial, have been developed that can be used to exclude the LAA successfully. In patients undergoing cardiac surgery, superiority of surgical over transcatheter LAAC is especially profound, including no foreign body protruding to the LA, lifelong closure without possibility of device embolization or migration and several non-thrombogenic benefits, significant in terms of comorbidity and risk factor management, including systemic blood pressure decrease, neurohormonal and systemic anti-coagulative changes [42–45]. Furthermore, specific benefits of thoracoscopic epicardial LAAC can also be observed in patients with a thrombus-containing LAA, where the presence of a thrombus poses a contraindication for catheter ablation. For these patients, a hybrid approach is a viable option. First, LAAC may be safely performed thoracoscopically using the AtriClip Pro V device, followed by catheter ablation as a second-step hybrid procedure [27]. Additionally, surgical isolation of the LAA reduces the risk of long-term atrial arrhythmia recurrence after surgical ablation, as epicardial device closure also serves as an electrical isolation. Surgical techniques for LAAC are presented in Figure 8. The main target for successful LAAC is the exclusion of LAA without leaving the pouch in its ostium.

While surgical closure of the LAA is now recommended as an adjunct to OAC in patients with AF undergoing cardiac surgery to prevent ischemic stroke and thromboembolism (IB), IIa recommendation is assigned to LAAC in patients with AF undergoing endoscopic or hybrid AF ablation by both ESC and AHA.

Growing evidence regarding the impact of LAAC on thromboembolism prevention has raised additional questions about its concomitant implications for AF ablation, as the LAA is known to be an extra source of atrial arrhythmia.

Two trials regarding hybrid ablation included LAAC as an obligatory procedure. In the CEASE-AF study, in which hybrid ablation including PVI, box lesion, and LAAC was compared with catheter ablation, 66.3% of patients undergoing hybrid treatment were in sinus rhythm after 2 years, compared with 33.3% of patients treated with catheter ablation [13]. Even more significant impact was observed in HARTCAP-AF, with 89% sinus rhythm in the hybrid treatment group after 12 months, compared to 41% in the catheter ablation population [11]. On the other hand, in the CONVERGE trial, where LAAC was not performed during hybrid ablation, the superiority of hybrid ablation was less pronounced (67.7% vs. 50%) [21]. Whether this difference was attributable to LAAC itself or transcatheter PVI remains to be resolved. Two large registries were analyzed to determine the impact of different AF-specific interventions on perioperative thromboembolic risk and long-term prognosis. Mehaffey et al., who studied 103,382 patients from large insurance registries from the US, observed that surgical ablation with LAAC was superior to LAAC alone in both three-year mortality (OR = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.88–0.93, p < 0.001) and composite outcomes (OR = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.81–0.99, p = 0.035) [46]. However, it should be noted that any AF-specific intervention was found to be better than no AF interventional treatment (OR = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.73–0.77, p < 0.001). Additionally, similar observations were made based on the Polish KROK registry, which underscored that the greatest, statistically significant mortality reduction was associated with surgical ablation combined with LAAC, followed by surgical ablation alone and LAAC alone [47]. In a single-center study by Kajy et al., it was shown that hybrid ablation led to AF-free survival equal to 59.3% at 4-year follow-up, with additional benefits observed from ligament of Marshall ablation and LAAC [48].

In a recently published systematic review of surgical techniques for LAAC, it was found that the stapler technique with excision of the LAA and clip deployment was associated with almost 100% procedure success rate, in comparison with non-device assisted techniques, whose success varied from 60.9% to 74.3% for suture techniques without LAA amputation and up to 91% with surgical amputation of LAA respectively [49]. Additionally, it should be noted that thoracoscopic device-assisted LAAC presents an opportunity for hybrid ablation in patients with thrombi in the lumen of the LAA.

The additional beneficial impact of LAAC during ablation is under extensive research. Recently, OPTION trial, RCT which included 1,600 patients to evaluate use of LAAC as an alternative to OAC after catheter ablation showed promising results, with a composite outcome of death from any cause, stroke or systemic embolism at 36 months observed in 8.5% of patients with LAAC and 18.1% of patients on OAC (p < 0.001) [50]. Based on up-to-date evidence, it may be expected that a combination of ablation with LAAC may lead to more favorable outcomes than each procedure separately. Future research should focus on the potential of OAC discontinuation after not only catheter ablation, but also surgical and hybrid ablation.

A summary of all trials regarding hybrid ablation, LAAC, and LAAC concomitant with hybrid ablation can be found in Table I.

Table I

Summary of trials regarding hybrid ablation and left atrial appendage closure

| Name | Population | Pts included | Intervention/control | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAAC | ||||

| ATLAS [65] | No preoperative AF, CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 2, and HAS-BLED ≥ 2 | 562 (376/186) | LAAC with AtriClip/no LAAC | 99% procedural success rate. 3.4% LAAC vs. 5.6% non-LAAC with TE. |

| LAACS [59] | Undergoing cardiac surgery | 187 (101/86) | LAAC/no LAAC | 6% vs. 18% serious adverse events (p = 0.05). |

| LAAOS III [60] | AF, CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 2 | 4770 (2379/2391) | LAAC/no LAAC | 4.8% vs. 7.0% stroke/embolism rate (p = 0.001) |

| SA vs. CA | ||||

| FAST [15] | AF, refractory to AAD, LA dilatation and hypertension or failed CA | 124 (61/63) | SA/CA | 65.6% vs. 36.5% success rate; 34.4% vs. 15.9% major adverse events (p = 0.027) |

| CASA-AF [17] | Long-standing persistent AF, EHRA symptom score > 2, LVEF ≥ 40% | 120 (60/60) | SA/CA | 26% vs. 28% success rate (p = 0.84); 18% vs. 15% serious adverse events (p = 0.65) |

| SCALAF [16] | Symptomatic paroxysmal or early persistent AF | 52 (26/26) | Minimally invasive SA/CA | 29.2 vs. 56% arrythmia-free survival (p = 0.059); 20.8% vs. 0% major adverse events (p = 0.029) |

| HA | ||||

| CEASE-AF [13] | Symptomatic, drug-refractory persistent AF, no prior ablation | 153 (102/51) | Thoracoscopic ablation + CA vs. CA and possible repeated CA | 66.3% vs. 33.3% success rate (p < 0.001); 10.8% vs. 9.6% major adverse events (p = 1.00) |

| CONVERGE [21] | Symptomatic persistent AF, refractory to AAD; LA size < 6 cm | 153 (102/51) | Subxiphoid ablation + CA vs. CA and possible repeated CA | 67.7% vs. 50% success rate (p = 0.036); 7.8% vs. 0% major adverse events (p = 0.053) |

| HARTCAP-AF [11] | Long standing AF, refractory to AAD, no prior ablation | 41 (19/22) | Thoracoscopic ablation + CA vs. CA and possible repeated CA | 89% vs. 41% success rate (p = 0.002); 5% vs. 5% major adverse events (p = 1.00) |

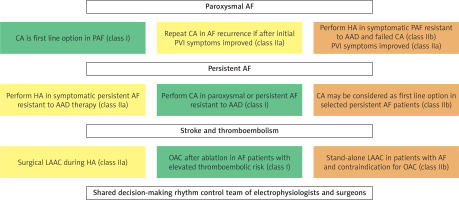

Guidelines review

The most recent guidelines underline the significance of shared decision-making of the rhythm control team, which should include both electrophysiologists and surgeons [3]. With the development of new techniques and constant changes in both surgical and percutaneous interventions, decisions regarding the chosen treatment should be made based on available equipment, site experience, the patient’s comorbidities, and the most optimal risk-to-benefit ratio. Based on recent guidelines, different recommendations are made for each treatment technique with potential alternatives, which should be chosen based on shared decision-making (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Key shared decision-making points regarding the potential use of hybrid ablation in the treatment of atrial fibrillation based on the ESC 2024 Guidelines [3].

AAD – antiarrhythmic drugs, AF – atrial fibrillation, CA – catheter ablation, HA – hybrid ablation, LAAC – left atrial appendage closure, OAC – oral anticoagulation treatment, PAF – paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.

Cost-effectiveness analysis of atrial fibrillation treatment

In one recent systematic review, interventional treatment was superior in terms of cost-effectiveness when compared with anti-arrhythmic drugs [51]. Additionally, research by Kawakami et al. performed in 2021 proved that concomitant ablation with LAAC is more cost-effective in comparison with ablation and OAC [52]. Furthermore, a cost-effectiveness analysis based on the LAAOS-III trial demonstrated that performing LAAC during cardiac surgery was cost-effective, a finding that held true even for the more expensive device-based closure methods when analyzed separately [53].

Broader heart team integration and surgical planning

AF, with growing incidence and significant social burden, should be recognized as a crucial clinical comorbidity, similar to coronary artery or structural heart disease, and treated as such in the decision-making process. It is well known that early optimal treatment of AF and management of its symptoms are crucial for well-being and an increased number of healthy life years, which healthcare specialists should prioritize. Shared decision-making between the rhythm control team, comprising electrophysiologists and surgeons, is essential to provide the best possible approach for treating AF in each individual. With the development of new techniques, such as hybrid ablation, the successful management of patients refractory to AAD or with multiple unsuccessful catheter ablation may not only be possible, but also achievable daily. Hybrid treatment extends beyond thoracoscopic ablation to a strategic, heart-team-based approach. Nowadays, with advancements in surgical technique, surgical ablation during cardiac surgery for patients with AF should be incorporated on a daily basis, even in procedures such as MIDCAB, mini-AVR, or MVR, in which successful ablation can be achieved using minimally invasive or robotic techniques. Preoperative and perioperative planning must include several key factors, including TEE guidance, LAAC, and documentation for post-op EPS evaluation.

Shared decision-making in rhythm strategy selection

The choice between catheter-based, surgical, or hybrid ablation must rest on a patient-centered, multidisciplinary decision, guided by clinical evidence, procedural feasibility, and personal values. The 2024 ESC Guidelines [3] emphasize that the rhythm control strategy in AF should be determined by a collaborative EP-heart team that includes cardiac surgeons, electrophysiologists, and other relevant specialists. However, the cornerstone of this team-based decision must be the informed and empowered patient. Indeed, patients must be advised that while multiple catheter ablations are common in paroxysmal AF management, these may prove burdensome and ultimately ineffective in persistent forms. Yet, for those with prohibitive surgical risk (e.g., frailty, severely reduced lung function), repeated percutaneous procedures may remain the safest available rhythm strategy.

Conversely, otherwise healthy patients with persistent or long-standing AF are likely to benefit from a comprehensive, one-time, initial, hybrid ablation, offering higher rates of sinus rhythm restoration, fewer repeat procedures, and lower readmission rates [13, 54, 55].

A critical distinction lies in stroke prevention. While catheter ablation alone does not reduce thromboembolic risk and often requires indefinite anticoagulation, and while percutaneous LAAC devices (e.g., Watchman, Amplatzer) carry nontrivial risks – including incomplete occlusion, device embolization, and the need for prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy [56], surgical LAAC achieves epicardial exclusion, no foreign body, and is associated with nearly complete elimination of LAA thromboembolism risk [50, 57–65]. Several studies and registries have shown that surgical ablation combined with LAAC reduces stroke and systemic embolism rates beyond catheter strategies alone, and possibly more effectively than percutaneous LAAC plus OAC [11–13, 18, 46, 50]. Nonetheless, thoracoscopic procedures, though minimally invasive, inherently carry surgical risks including pleural complications, bleeding, and need for general anesthesia, and these must be explicitly weighed during consultation. Tailoring the rhythm strategy – catheter, surgical, or hybrid – must include:

Transparent communication of risks, benefits, and alternatives.

Explanation of long-term implications, including stroke risk, bleeding risk, and reintervention potential.

Consideration of patient values, including lifestyle, aversion to anticoagulation, tolerance for repeated interventions, and willingness to undergo minimally invasive surgery.

Ultimately, the most effective rhythm management occurs not when physicians choose a strategy for the patient, but when patients are fully informed and determine a plan with their physicians.

Institutional requirements and technical prerequisites

Although hybrid ablation is fundamentally safe, its complexity demands structured team integration, training, and adequate facility capacity. A learning curve of approximately 20 cases has been described for convergent procedures and minimally invasive thoracoscopic hybrid protocols [8]. For sustainability and proficiency, a minimum of 50 hybrid procedures per year is suggested. Key institutional requirements include:

A dedicated hybrid surgical-electrophysiology team.

Availability of thoracoscopic instruments, 2D/3D vision systems, and general anesthesia infrastructure.

Experience in thoracoscopic cardiac surgery, including TT-MAZE and MICS procedures.

Mobile or dedicated EP system and mapping team if single-stage procedures are performed.

Collaborative culture between EP and surgical departments to support case planning and postoperative coordination.

For staged procedures, separate access to an EP lab suffices. If simultaneous hybrid procedures are performed, a hybrid OR or mobile EP setup is required.

Future directions and appeal to the National Health System

We advocate for the formalization of electrophysiology-heart teams, the integration of AF strategies into surgical planning, training in both open and minimally invasive ablation techniques, and the development of registries. Hybrid ablations should be a reimbursable category with support for dual-specialist models and follow-up pathways.

Conclusions

Hybrid therapy offers a pathway toward durable rhythm control in complex arrhythmias, including persistent AF. It provides unique characteristics of both surgical and catheter ablation, with an acceptable complication profile. Shared decision-making between the rhythm control team, comprising electrophysiologists and surgeons, is crucial for optimizing treatment and improving patient-oriented outcomes. With the rapid development of new hybrid techniques, the national infrastructure must be upgraded so as to meet the requirements associated with implementing hybrid technologies in everyday practice.